Russian sport ban raises barely a ripple

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/12/2019 (2184 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Once, the news that a world power had been slammed with a four-year ban from major international sporting events due to a long-running doping scandal might have made an explosive landing. In 2019, however, the news seemed to make little more than a ripple.

So it seemed this month when the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) announced that Russia, as a nation, would be banned from competing in — or hosting — big events, including the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. (The ban does not apply to events that falls outside WADA’s definition of “major,” including next year’s European soccer championship, which Russia is co-hosting.)

This does not mean all Russian athletes will be out in the cold. Under the terms of the ban, athletes who can prove they compete clean will be allowed to participate under a neutral banner, similar to the “Olympic Athlete from Russia” designation at the 2018 PyeongChang Olympics, during which the Russian Olympic Federation was suspended.

Russia has pledged to appeal WADA’s latest decision via the sport’s top arbitration court.

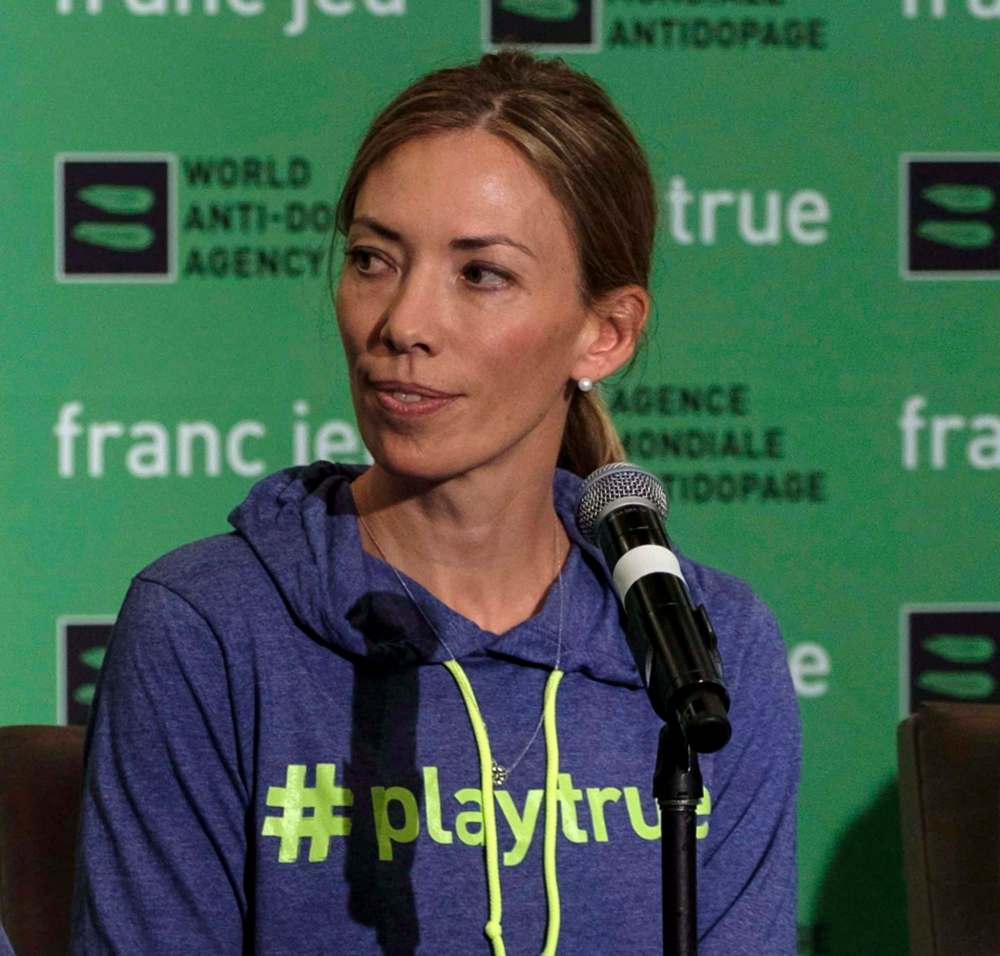

Within sport, the reaction to the ban was both mixed and, in places, heated. Many athletes and sport professionals — including former Canadian Olympian Beckie Scott, who last month ended a six-year term on WADA’s athlete committee — thought the ban didn’t go far enough. To them, the fact athletes from Russia will still compete in the games, just without a flag or national anthem, amounts to little more than a symbolic punishment against Russia’s long history of flouting anti-doping rules.

Others applauded the decision, including two-time Olympic gold medalist Penny Heyns, a retired swimmer from South Africa. As a member of the WADA investigation panel, Ms. Heyns lobbied hard for Russian athletes to retain a path to competition.

Navigating between these points of view presents a thorny test of balancing sport’s professed values. On one hand, if sport is a celebration of human potential and a testament to following one’s dreams, then it would be cruel to deny those who, individually, have done nothing wrong.

On the other hand, international sport is a platform for global co-operation that goes far beyond individual achievement. If an infraction is grave enough, it is right for the international sporting community to issue a complete rejection. The question, then, becomes where does one draw the line? Is Russia’s long and flagrant disregard for the fairness of sport, and the institutions charged with protecting that fairness, a sufficiently serious insult to justify more stringent repercussions?

Here is something to consider: When the news of the WADA ban landed, the general public seemed to greet the news with at best moderate interest. By the end of the day, headlines about the ban had largely fallen off lists of most-read subjects, replaced by news of Donald Trump’s latest political woes and the last days of the United Kingdom’s elections.

This lack of any shock may well be the product of a public that, over the years that news of Russian doping has shaken sport, has grown cynical on the whole topic. In this way, Russia’s systemic doping and seemingly ceaseless attempts to evade sanction could well leave a stain on sport that spreads far outside its borders, and lasts long after this ban is over.

The country will not raise a flag at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. But its influence will still be felt in the trust the world has, or does not have, in the value of fair competition. For undermining that fundamental peg, perhaps a more stringent punishment would have been appropriate.