Prairies prudent to pursue pulse-product possibilities

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/09/2019 (1985 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The Canadian Prairies have long been known as the “Breadbasket of the World” for their role in supplying the globe with cereal grains.

But as global food trends change, demand for sources of plant protein has skyrocketed. As environmental groups, including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, point to livestock’s hefty contribution to climate change, consumers are demanding alternatives to animal protein.

Manitoba is at the vanguard of this technology; the Food Development Centre in Portage la Prairie was instrumental in developing the meatless, soy-based Impossible Burger (a competitor of the popular Beyond Meat product, it’s available at Burger King locations in the United States).

The Roquette pea-processing plant, currently under construction in Portage la Prairie, expects to process 125,000 tonnes of yellow peas a year for proteins aimed at the alternative-meat market, while a new $65-million Merit Functional Foods Corp. plant in Winnipeg’s CentrePort will be processing canola and peas for soluble protein for use in beverages.

The province is poised to be a leading provider of what’s being called “sustainable protein,” but as experts at the recent Manitoba Protein Summit pointed out, a strong communications strategy is key, with a concerted effort needed to inform major centres in the U.S. about developments and advances being made in Canada.

Co-operation is another key to a successful strategy, with a focus not just on growers but on researchers and processors. Proponents of the Protein Highway — a collaboration among the Prairie provinces and Midwestern U.S. states to research, develop and promote proteins from pulses and grains — realize it’s a challenge to overcome traditional resistance to the idea of working with, not against, competitors.

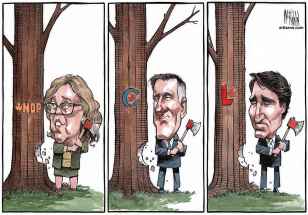

The province has announced local initiatives to co-ordinate industry, academic and government efforts in developing the plant-protein industry. But getting on the Protein Highway requires active cross-border collaboration; in a province led by a premier not necessarily known for his ability to play well with others, that’s not always a given.

It’s imperative to strike while the lentil is hot. It’s not every day that an industry is prepared to dictate the direction of a trend, rather than merely react to a need. A pan-Prairie pooling of resources could accelerate the wider acceptance of beans, hemp, peas and canola as protein sources; right now, those resources are isolated in individual universities, research centres and government departments.

Canada has long focused on commodities for export, but extracting the value-added products from protein-rich plants means looking beyond bulk export. It took Canada years to begin crushing its own canola for oil; it shouldn’t take so long to locally implement the widespread ability to handle such processes as milling pulses, including lentils and chickpeas, for flour or using canola meal to create protein-rich milk and tofu substitutes.

Manitoba already has a seat at the table of the Protein Highway, which just named Manitoban researcher Lee Anne Murphy to its first board. But working toward a formal governmental collaboration with Saskatchewan and Alberta would only fuel the expansion of these sustainable industries in all three provinces.

Meanwhile, the Prairies might need to work on a new nickname: “The Pea-Protein Isolate Basket of the World” doesn’t have quite the same ring.