U.S. moon landing relied on Canadian ingenuity

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/07/2019 (2334 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

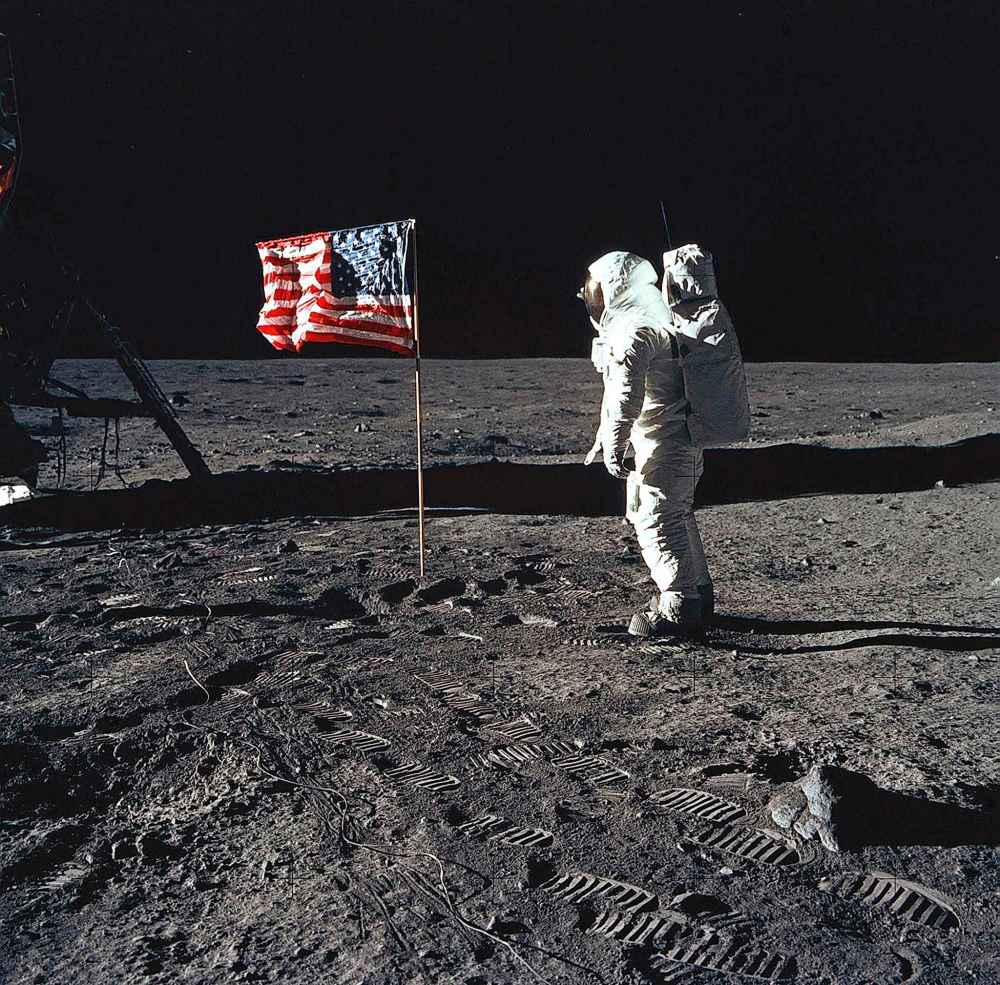

This week, the world is celebrating the 50th anniversary of one of the pinnacles of 20th-century achievement — humankind’s first landing on the moon.

It will be a tribute to American ingenuity and courage, but also a salute to Canadian know-how and technology, without which Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong would not have set foot on the dusty lunar surface on July 20, 1969.

Canada’s remarkable contributions to the lunar landing were born out of what some consider a tragedy — the federal government’s decision to cancel the Avro Arrow supersonic jet project on Feb. 20, 1959.

“Canadians contributed a massive amount to the space race and Apollo,” Robert Godwin, then curator for the Canadian Air and Space Museum in Toronto, told the Truro News in 2010. “Not meaning it to be a derogatory remark, but the Americans benefited greatly from the demise of the Arrow. All of these genius (Canadian) engineers ended up going to help put men on the moon.”

NASA sent officials to the Avro plant outside Toronto, three weeks after its demise, and recruited 13 Canadians who proved instrumental in carrying out U.S. president John F. Kennedy’s pledge to send humans to the moon.

Among those recruited was former Avro engineer James Chamberlin of Kamloops, B.C., who is hailed as the first NASA expert to realize that flying a single spacecraft directly to the moon wasn’t the best option.

It was Mr. Chamberlin who proposed the lunar orbit rendezvous plan — the two-vessel concept of a command module that would orbit the moon and a lander that descended to the moon’s surface before returning the astronauts safely to the command module.

The design of the iconic landing module itself is largely credited to the genius of another laid-off Avro engineer, Sarnia, Ont.-born Owen Maynard, who became chief of systems engineering for the Apollo program.

Maynard, who died in 2000, was one of the first — if not the first — to sketch a design for the lunar excursion module. “He drew this four-legged, spider-like landing craft that… used the bottom half as a launch platform to come back (to the orbiter) again,” Mr. Godwin noted.

Before Mr. Armstrong’s booted feet famously stepped onto the crater-pocked lunar surface 50 years ago, the first legs to settle into the moon dust were Canadian. The aluminum legs of the lander were created by Heroux Machine Parts Ltd. (now Heroux-Devtek) of Longueuil, Que., with an innovative compressible honeycomb design to absorb the shock of landing on the moon.

But the Canadian connection does not end there. Calgary’s Bryan Erb was another Arrow engineer scooped up by NASA, and he helped to create the unique heat shield on Apollo 11’s re-entry capsule, which protected the astronauts as they returned to Earth at the speed of a ballistic missile.

After returning from the moon and being scooped from the ocean, the astronauts, in their airtight biological containment suits, were met on board the recovery helicopter by yet another Canadian, flight surgeon Dr. Bill Carpentier of Lake Cowichan, B.C.

Dr. Carpentier checked the crew’s physical condition and his head can be seen famously bobbing behind the astronauts when then-president Richard Nixon greeted them through the window of their quarantine facility on board the USS Hornet.

Fifty years after it all happened, it would be fitting today for Canadians to reflect on the fact that Neil Armstrong’s “small step for (a) man” required a giant helping hand from his neighbours to the north.