Manitoba needs a better road-safety strategy

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/05/2019 (2399 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

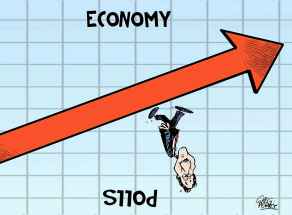

A number of high-profile pedestrian deaths resulting from collisions in Winnipeg this year has road safety on the minds of many. The question is, what to do about it?

Manitoba’s Road Safety Plan 2017-2020 highlights a grim statistic: despite the fact some progress is being made — traffic-related deaths declined from 120 in 2006 to 80 in 2015 — motor-vehicle collisions are the province’s fifth-leading cause of injury-related deaths.

Clearly, action is required.

‘It’s time to take a long-term approach, as Sweden did, and learn from what other jurisdictions, such as B.C., are doing’

Public awareness campaigns are one approach, to encourage safer driving practices and better awareness for motorists and pedestrians who use our streets and sidewalks. MPI’s “Save the 100” advertisements highlight individual responsibilities for making our roads safer, with emphasis on factors such as distracted driving, impaired driving and speeding.

Actually making the most dangerous sections of road safer, however, is a stickier proposition.

City Coun. Janice Lukes has pushed for a traffic safety initiative since 2016, aiming to get traffic fatalities down to zero.

The initiative, Vision Zero, was first developed in Sweden in 1997 and focuses on the design of infrastructure and how it is used, analyzing data to create safer spaces.

And it’s working: Sweden has one of the lowest annual rates of road deaths in the world, at three per 100,000. Pedestrian fatalities there were reduced by half within five years.

Other jurisdictions have adopted this outlook as well: in 2014, New York City launched a plan employing traffic data and improved engineering to get traffic deaths to zero within 10 years.

Clearly, investing in our roads, walkways and other infrastructure with a view to safety is critical. Here’s another question: how do we pay for it?

In this, the province has a role to play. The previous New Democratic government floated a proposal to devote funds from MPI to improve high-risk spots. That went nowhere, thanks to vocal opposition over the prospect of the insurer funding infrastructure upgrades rather than returning surplus funds to ratepayers.

The fact that safer intersections reduce the risk of accidents and save lives must not have been enough justification for those opposed, but — if money is the issue — the additional knowledge that reducing the number of collisions also reduces the number of claims and thus lowers premiums should have been. It’s also worth noting that decreasing accident and injury numbers lessens the financial burden on the taxpayer-funded health-care system.

Other jurisdictions have already taken this approach. The Insurance Corporation of British Columbia partners with local government to pay for safety-related road improvements. According to a 2015 evaluation, the initiative led to an average 24 per cent decrease in severe collisions over a three-year period.

Manitoba has taken a lot of flak for not devoting more money to road and highway repair. Yet, the much-criticized increase to the provincial sales tax under the NDP was intended to fund infrastructure, something the opposition Progressive Conservatives attacked at the time. Even if the Pallister government were not philosophically opposed to spending PST income on roads, the revenue loss created by its promised-and-delivered one percentage point PST cut (effective July 1) would make such an investment difficult to achieve.

We use our roads, highways, sidewalks and intersections every day, and pointing fingers doesn’t make any of those routes safer. It’s time to take a long-term approach, as Sweden did, and learn from what other jurisdictions, such as B.C., are doing.

Because as the various safety campaigns make clear, the only number of traffic deaths we can all live with is zero.