Atonement requires empathy, not self-pity

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/09/2018 (2640 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

What does atonement look like? Does repentance always lead to forgiveness? Does forgiveness go hand in hand with forgetting?

These are thorny questions in a time when the #MeToo movement has seen celebrities accused of sexual harassment and abuse lose their livelihoods and place in the limelight.

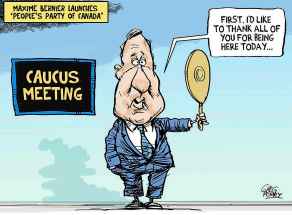

They’re the questions former New York Review of Books editor Ian Buruma claimed to be asking by commissioning a controversial story that appears in the October issue of the magazine. Reflections From a Hashtag, a personal essay by disgraced CBC Radio host Jian Ghomeshi, was published online last week.

Buruma, who left the magazine in the wake of the controversy created by the essay’s online publication, told Slate the intent was not to give Ghomeshi, the former Q host who was found not guilty in 2016 of four counts of sexual assault and one count of choking, a platform to exonerate or explain himself. Rather, it was to examine “what happens to somebody who has not been found guilty in any criminal sense but who perhaps deserves social opprobrium, but how long should that last, what form it should take.”

That may have been Buruma’s intent. But to address those questions requires a subject who believes he needs to repent. Ghomeshi’s 3,400-word piece veers from narcissism (“One of my female friends quips that I should get some kind of public recognition as a #MeToo pioneer”) and self-pity to prevarication and outright obfuscation without ever dipping a toe into true remorse.

“What I am is someone who has had a crash course in empathy,” he writes. No, not empathy for the woman he harassed. “I now have a different way of seeing anyone who is being attacked in the public sphere,” he continues, a roundabout way of saying he feels sorry for himself.

If Ghomeshi’s goal was to prove himself worthy of resuming his place in the public eye, it could not have backfired more spectacularly. It’s the tone-deaf work of a man for whom the spotlight is clearly dangerous, amplifying his worst impulses.

Some might argue the state of exile in which Ghomeshi finds himself is an apt sentence, delivered in the face of a justice system inadequately equipped to deal with sexual assault cases. When is that exile over? Perhaps that question hinges on the mistaken idea that repentance necessarily leads to the resumption of one’s former glory — that atonement wipes the slate clean.

Ghomeshi comes nowhere near atonement — he can barely bring himself to confess to being demanding and critical — but even if he had prostrated himself before the people he claims he didn’t hurt — the more than 20 women who allege he slapped, punched, bit, choked or smothered them — that shouldn’t mean he assumes once again the mantle of a popular radio personality, gala host and man-about-town.

Repentance does not come with a reward. Famous men who use their fame to facilitate bad behaviour — which Ghomeshi admits he did — should not have it restored to them. Nor should they be awarded space on stages or given pages in prestigious publications to revictimize those who suffered at their hands.

The question of who stands in judgment of those seeking absolution is murky, but it’s certainly not the readers of the New York Review of Books. And those who would ask the question should also be asking themselves why, once again, they have given the words of an admitted bully more credence and weight than the words of those he harmed.