Winnipeg study to put meth treatment under microscope

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/08/2019 (2300 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the battle against methamphetamine, knowledge will ultimately be the key to getting the upper hand. Unfortunately, the data about meth, a drug that varies wildly in its formulation and effects, is lacking.

That may be changing, however, thanks to a groundbreaking study undertaken by the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service and Shared Health that could help the health-care system screen patients and design more effective treatment options.

The study will track meth users from their first point of contact with emergency responders, all the way through to their discharge from a hospital. The study will look at early-stage symptoms, courses of treatments, length of stay in hospital, and outpatient treatment and support prescribed.

In particular, the study will try to determine the effectiveness of olanzapine, an antipsychotic medication now administered to meth users in Winnipeg almost immediately after contact with paramedics.

“This is the best way for us to move towards evidence-based medicine,” said Dr. Rob Grierson, the WFPS medical director.

The study results — expected early in 2020 and should include data on more than 1,500 patient interactions — arrive at an opportune time.

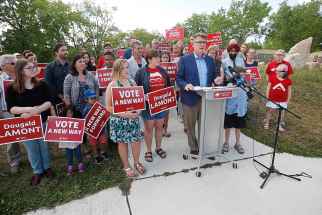

All three main political parties in the current provincial election campaign have pledged new, stand-alone meth treatment facilities to relieve the strain on hospital emergency departments. Winnipeg ERs have been overwhelmed by patients suffering from meth use; at Health Sciences Centre, the number of people suffering from meth has gone up by more than 1,200 per cent in the last year alone.

However, Grierson said given the unpredictable nature of the drug, it’s not entirely clear how many meth users could be diverted from the hospital system. This is largely due to the fact there is so little research on how users react to different kinds of treatment, including olanzapine.

In November, Winnipeg became the first city in Canada to allow first responders to administer olanzapine. Normally a drug used to treat bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, it is currently the medication of choice to address the psychosis that often accompanies meth use.

In the first five months of 2019, Winnipeg paramedics administered nearly 400 doses.

However, even in jurisdictions that have used olanzapine on the front lines, there is a decided lack of data on how effective it is in de-escalating psychosis and violence, Grierson said.

“This is the best way for us to move towards evidence-based medicine,”

– Dr. Rob Grierson, WFPS medical director

The Winnipeg study will help medical professionals — from first responders all the way through to emergency physicians and mental health specialists — better screen meth users at an early stage and better predict the range of symptoms they might exhibit, Grierson said.

It will also help local health officials determine whether some patients can indeed be sent safely to stand-alone treatment facilities that would likely have neither the security nor the tertiary care available in hospital setting.

Grierson said, in theory, 75 to 80 per cent of meth patients could be diverted to non-hospital facilities because they are generally co-operative and willingly agree to take olanzapine. (As an oral medication, first responders require verbal consent before administering the medication.)

Outside of that group, about 10 to 15 per cent of meth users have other serious medical conditions (heart attacks, strokes, trauma injuries) that require transport to hospital.

That leaves about five per cent of users who are volatile and unpredictable, often displaying violent behaviour. Those patients as well would need to be cared for in a hospital setting, Grierson said.

However, there are many different formulations of meth on the street, and each one will affect users in slightly different ways. As well, each individual user may have a different reaction even if they are ingesting the same formulation.

Political parties have been deliberately vague about exactly how their proposed stand-alone treatment facilities would be structured, but Grierson said there must be a minimum level of medical expertise available at all times to ensure the safety of patients. That will mean advance treatment nurses, or nurse practitioners along with mental health and addictions workers.

It may even be necessary for these facilities to have an on-duty physician, or access to a physician, to determine when a patient needs to be transferred back to a hospital because symptoms of withdrawal have become more volatile.

Ultimately, any facility of this kind will only be successful if there is community-based treatment available on the back end, Grierson said.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.