Losing the vote in North Dakota, where the streets have no names

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/10/2018 (2602 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The American midterm elections are next Tuesday.

And the most American of American traditions is playing out before our very eyes.

I’m not talking about democracy. I’m talking about erasing Indigenous peoples.

In early October the Supreme Court allowed a voting requirement in North Dakota that directly impacts Native Americans and threatens them from participating in the midterms.

Under the requirement, all North Dakota voters must have a residential street address. The issue is that most Native Americans on the five tribal reserves in the state have post-office boxes. The reasons for this are due to a myriad of factors: rural life, a lack of services and poverty. In other words: history.

Native Americans in North Dakota make up about five per cent of the state’s 570,000 eligible voters. That’s about 28,000 voters. Estimates say that about 10,000 of them lack proper identification and the means to get ID made. Some don’t even know their street address and some tribal areas don’t have street names.

The only other group most impacted by this ruling is homeless people.

So, why would state legislators suddenly enforce a law that ostracizes and marginalizes Native American voters in a state where Indigenous voice matters?

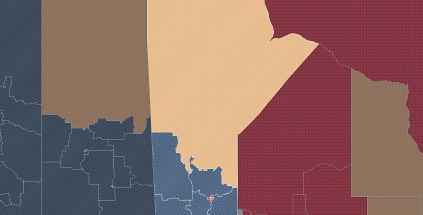

It’s this simple: North Dakota is strictly Republican. U.S. President Donald Trump won the state in 2016 with 63 per cent of the vote. Republicans hold virtually all of the statewide positions and hold majorities in both houses of the state legislature.

Yet, in 2012, North Dakota elected its first female Democratic senator, Heidi Heitkamp. A former businesswoman and lawyer, Heitkamp is best known as the state’s popular attorney general who took on the tobacco companies in the late- 1990s and secured the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.

So, in the waning days of President Obama’s term, North Dakota elected a Democratic senator. A right-leaning Senator, but a Democrat nonetheless.

Heitkamp won that election by less then 3,000 votes. That’s a millimetre in U.S. voting standards.

A large portion of Heitkamp’s support was found in North Dakota’s five Native American tribal nations. Most voted for her.

So, with little surprise, Republicans began work almost immediately after Heitkamp’s election to find a way to defeat her. In 2013 the state legislature began debate on implementing a new voter ID law to require street addresses for all eligible voters.

For years, state judges rejected the law, blocking it on grounds that it unfairly and disproportionately impacted Native American voters. One judge even wrote in a decision that, “The state has acknowledged that Native American communities often lack residential street addresses. Nevertheless, under current state law an individual who does not have a ‘current residential street address’ will never be qualified to vote.”

The state primaries came and went under the same voter ID rules as in the past.

Then, in September, the United States Court of Appeals lifted the injunction by the state court and the Supreme Court refused to reinstate it in October.

And, just like that, thousands of Indigenous voices were erased. It’s that easy.

Heitkamp voted against Brett Kavanaugh’s ascension to the Supreme Court and that resulted in a loss in her base support in the state. Like I said, the state is overwhelmingly Republican.

A poll last week suggests that she is now trailing her opponent, Republican Kevin Cramer, by 16 points, 56 per cent to 40.

The election is not over, though. Heitkamp’s election bid was boosted by a record $12.5 million in donations after her “no” vote on Kavanaugh — with more dollars still rolling in.

It appears that 5,000 Native American votes may matter, after all. Under boundaries also introduced by state Republicans, fewer Native American votes means precincts that turned blue in 2012 will now turn red.

This is a big deal. A Heitkamp loss would make the chances of Democrats taking the Senate almost impossible. North Dakota is one of the most crucial seats U.S. Democrats need to have a chance to take the Senate and challenge Trump federally.

This is evidence of one of the worst and most egregious examples of voter suppression in U.S. history. North Dakota Republicans have found a way to silence voters who could produce change federally and they’ve have used Native Americans to do it.

The great American tradition of the Indigenous erasure continues.

Now, activists and tribal leaders are working around the clock trying to issue new voter IDs with street addresses. Tribes have swallowed all costs and are even issuing cards free of charge. This valiant struggle includes driving elders to county offices, filling out dozens of forms and jumping over several bureaucratic hurdles to have new cards certified.

But time is running out.

America’s greatest tradition is very much alive.

America is great again.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, October 30, 2018 9:54 AM CDT: Corrects typo

Updated on Wednesday, October 31, 2018 10:56 AM CDT: Corrects number of eligible voters, and number of indigenous eligible voters.