Tradition, trust and turmoil Massive challenges on the global media landscape have not altered the enduring Free Press mission: telling your stories, preserving this community's history

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/10/2018 (2718 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

You never forget the first time you see the newspaper presses, these vast mechanical maws roaring like jet engines, gobbling up raw newsprint and transforming it into something to be held and opened and savoured.

The sound seems to fill up your ears, your lungs, your bones. A working song, mechanical, magnificent.

The sadness is that one day, those presses will probably fall silent. There’s no telling exactly when. Only that the march to digitize our culture is not slowing, and someday all the news there is to read will wink out from a screen.

When the presses fall silent, so too will the small pleasures of many consecutive generations. The mingling smells of ink and coffee; the sound of sparrow song, accompanied by the rustle of a morning paper; and the feel of it all.

Yet I know this much: however our industry will change, the core of what animates a newspaper will remain.

And I think of that this weekend, the final days of National Newspaper Week, a campaign crowned by the hashtag #NowMoreThanEver. It is a call to celebrate our work, and our survival, in an industry rent asunder by technology.

It is no secret that the print media industry is struggling. The reasons for this are both complex and, in part, also quite simple. Online giants such as Facebook broke revenue models on which regional publications once thrived.

As of yet, no regional newspaper has found a totally safe haven. New models are constantly being explored, tweaked, tested. Some publications are luckier than others — more readers, better owners. No one has been left unscathed.

On the ground, the impact of these changes has been seismic, attritional. Over the past 10 years, I have watched many better journalists than I across Canada fall out of the industry, their talent lost to readers — often, forever.

But the work goes on, and newspapers do, too — never forgetting the stormy days behind and ahead. In long conversations over pub drinks, print journalists whisper to each other their pain. Survivor’s guilt. Anxiety. Grief.

When the weight of this moment gets too much, I find my solace in history.

Because history, more than newsprint, is the stuff papers are made of. The Free Press office itself is filled up with history, liberally doused with it, so much that we almost don’t know what to do with this inheritance of old things.

In a drawer in some unused corner of the newsroom sits a copy of the paper’s very first edition, dated Nov. 30, 1872. Nearby, the door to the photo archives, thousands of black-and-white prints of vanished Winnipeg places.

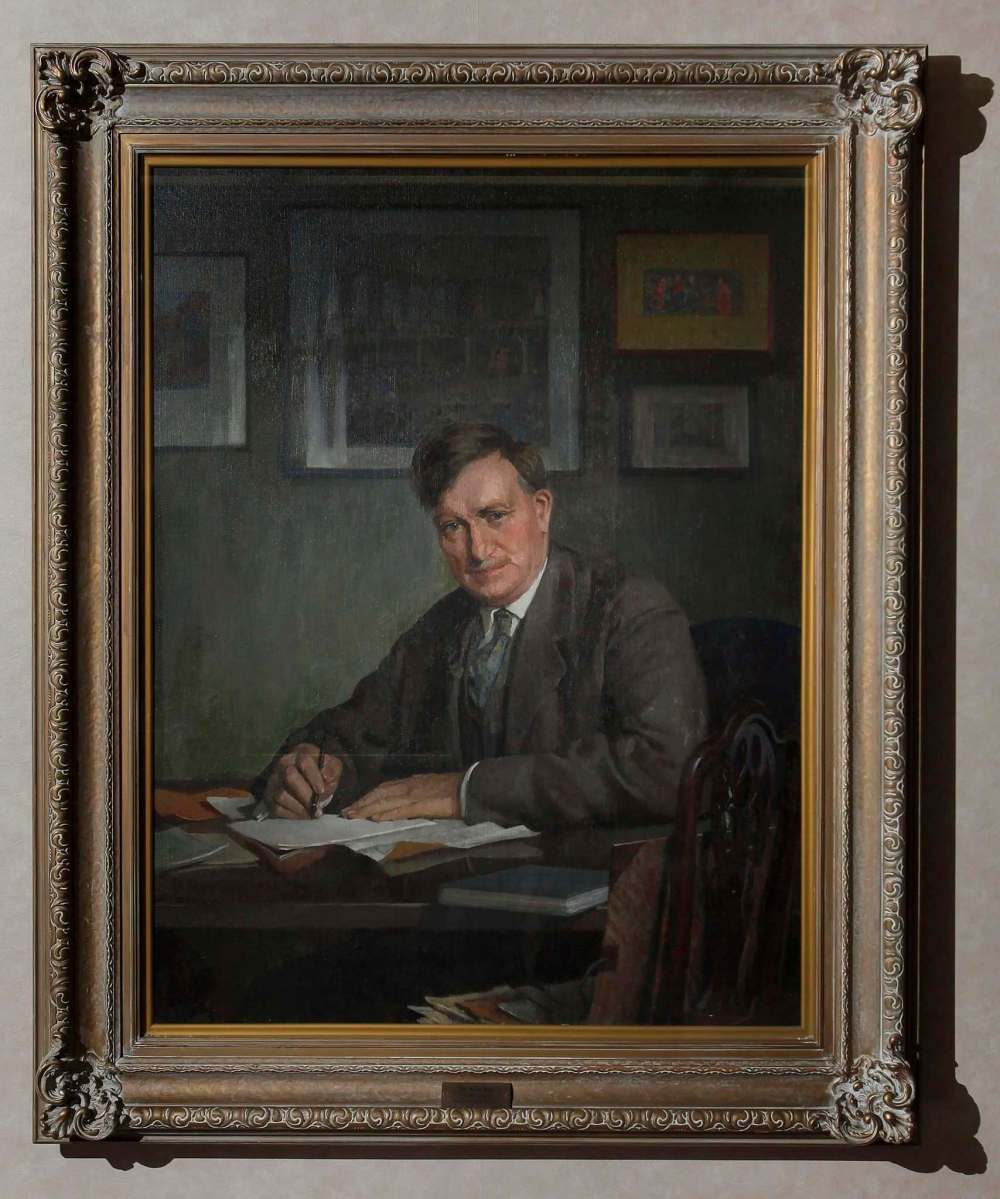

The old maroon leather armchair, near my desk; I’ve sat in it for many long, pondering moments. I didn’t know until recently that it belonged to iconic Free Press editor John W. Dafoe, who guided the paper from 1901 until 1944.

I found one of his old notebooks once, in a drawer next to my desk. Notes about meetings and politics, written in pencil and elegant script. I smiled, to see the notebook was only half-filled — so are most of mine, to be honest.

But those are just artifacts. The true history of a newspaper is held by its words, and here, too, I find guidance.

Sometimes, on rainy days when work is slow, I open up the Free Press archives, pick a date long ago and start reading. I run my eyes over old advertisements for tinned meat and mail-order dresses, smiling at the low prices.

Between those ads, mixed in amongst news of wars and political scuffles, are the stories of everyday people. And those are the things that capture me most, and remind me now of the mission we have been entrusted to uphold.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, newspaper writing was vivacious and often gleefully political. They were also breezily, unself-consciously local, at a time when their pages were the threads that bound communities together.

No detail of those communities’ lives was too small to notice. In old papers, short briefs about 16-year-olds’ birthday parties in Elmwood, complete with the number of guests, the entertainment enjoyed, the presents.

Those were the days when people quoted in the paper were credited not just by name, but by address.

These specific practices are not imaginable now. As our city grew bigger, and communities less connected, our sense of both privacy and what constitutes newsworthiness grew more pronounced. That’s OK, things change.

But the core mission of those old stories lingers. It never went away. It sparkles every time my colleagues write about a high school basketball game, or a festival, or interview an average Winnipegger who did something special.

This is us. These are our stories. They are not always the ones that change the course of a province, or a city. But taken together, they create a public record of who made our communities a home. They tell a tale of our belonging.

Even today, it is likely you could pluck near any paper from the 146-year-old archive of the Free Press, pick a few names found therein and find descendants still living in Manitoba. Still part of our story. Still spinning an unbroken thread.

History is not written only by plutocrats or politicians. It is made every day, in every neighbourhood where we are living. Everyone who came before built our world, in some way, and they are remembered in a newspaper’s pages.

The industry has changed, since those early days, but the work goes on. There are more stories to be told about ourselves now, than ever. As long as the presses roar, as long as words fall from typing fingers, we will tell them.

For that, we in the newspaper have much to be thankful — above all to you, for reading along with us. It takes a reporter to write a story, but it takes readers for those stories to enter the historical record as conversations.

One day, decades from now, maybe some young newspaper journalist will be thumbing through some archive, probably digital. And she will find these conversations, and know that, today, we are proud to carry them on.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.