Gap between haves and have-nots widening in kids’ sports

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/08/2018 (2669 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

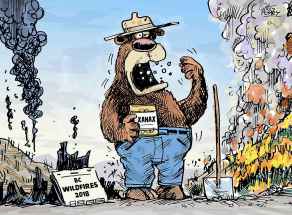

We cling to a romanticized view of sports as a meritocracy.

In a world in which everything from the tax system to photo radar seems stacked in favour of the rich, we treasure the idea that sports is one of the last places where the playing field is level and we’re all judged strictly on the merits of higher, faster, stronger.

If only it were so.

I’m not sure it was ever true that we all line up at the same starting line when it comes to sports, but what has become increasingly clear is that it’s less true now than ever before that a poor kid has the same chance to excel in sports as a rich kid.

I was reminded just how stacked the deck is in favour of the children of a privileged few by an especially obnoxious piece in the homes section of the Wall Street Journal last week that celebrated the millions of dollars American parents are spending to build their kids private gyms, courts, fields and in-home training facilities.

One Florida family “spent roughly $120,000 to build a 93-by-40-foot pro-quality turf soccer pitch behind their 8,135-square-foot home.” They use the field to have a professional coach they’ve hired teach their 14-year-old son the intricacies of the beautiful game.

Then there’s the Silicon Valley millionaire who built an indoor hockey rink, 110-yard golf hole and indoor gym for his precocious sons. You will not be surprised to learn that all four of the guy’s kids earned sports scholarships to major U.S. colleges.

Or how about Carolina Hurricanes head coach Rod Brind’Amour, who spent $80,000 installing for his kids “a volleyball / basketball / hockey facility — with a baseball batting cage and small putting green — in the backyard of his custom home in Raleigh, N.C., about 10 years ago.”

You will not be surprised, again, to learn Brind’Amour’s 20-year-old daughter, Briley, is on a volleyball scholarship to Virginia’s James Madison University while his 19-year-old son, Skyler, was an Edmonton Oilers draft pick in 2017 after growing up in a home that had its own private synthetic ice surface.

Pitchforks and torches were inspired by people such as this.

According to the Journal, $3.6 billion was spent in Canada and the U.S. last year on youth sports facilities. Almost 10 per cent of that — $320 million — was spent by wealthy parents on private facilities for their kids that the public will never see, much less use.

Now look, rich people are allowed to spend their money any way they want. If you can find someone dumb enough to give you millions of dollars a year just because you can shoot a frozen disc into a six-by-four foot net, that buys you a lot of freedom. I wish I had a skill that was in high demand despite serving no useful social purpose.

And it also should not surprise anyone that the rich, like the rest of us, want to give their kids every advantage in life.

But let’s just not pretend that a bunch of kids who were born on third base (on their own private backyard baseball diamond) have now hit a home run.

Have you ever wondered why the children of professional athletes disproportionately become professional athletes themselves?

Some of it is surely “nature” — if your father was uniquely physically gifted, there is good chance you will be, too. And some of it is surely “nurture” — if your mother was an Olympic gold medallist, she is going to instil in you an attitude towards everything from diet to exercise to competition that will be useful to you as a budding athlete.

But a lot of it also simply comes down to money. Successful athletes such as Brind’Amour have the kind of bucks the rest of us don’t and they can use that buying power to provide their kids with the kind of equipment, training and sports opportunities that the rest of us can only dream of giving our kids.

And that’s what the rich have been doing, with increasing frequency. The U.S. youth-sports economy — a catch-all that includes everything from the construction industry that builds these private in-home sports facilities to private coaches to specialized training apps — has grown 55 per cent just since 2010, according to Time magazine.

You know what else has grown dramatically since the Great Recession? The gap between the rich and poor.

And with that widening income gap has come a widening gap in sports participation. According to a study by the Aspen Institute, children age 6-12 from homes with a family income below $25,000 per year are three times as likely to be inactive — meaning they didn’t play a sport of any kind during the previous year — than kids from homes with a family income greater than $100,000 per year.

Ponder that the next time you hear someone rhapsodizing about how sports is the great equalizer that brings people of every walk of life together in the spirit of… blah, blah, blah. You know the speech.

Money talks, and the reality is the kids most likely to receive athletic scholarships to universities and colleges are increasingly the same kids who least need those scholarships, the children of the wealthy.

And that now also includes basketball, a sport long held up in the U.S. as an example of sport’s ability to raise the economically disadvantaged up out of poverty. According to one recent study, more than 80 per cent of NCAA Division I basketball players on a scholarship now come from families in which at least one of the parents also has a college education, a key indicator of economic mobility.

Think we’re better than that up here in Canada, home of socialized medicine and a better social safety net? Maybe. But don’t kid yourself — both our national sports are also elitist as hell.

Indeed, lacrosse, our official national summer sport, might be the most elite sport of all. A 2010 study found that less than 10 per cent of lacrosse players in the NCAA are non-white and less than two per cent are black, leading Forbes magazine’s Bob Cook, who’s done some great writing on this subject, to conclude: “Lacrosse’s rich white people ‘problem’ is a feature, not a bug.’”

And hockey, Canada’s official winter sport? Well, your kid can have all the skill in the world these days, but unless you also have the money to pay for a synthetic private ice rink, hockey school, a private trainer, $200 sticks and thousands a year in fees and costs that go with playing on a top travel team, he or she is, in all likelihood, going to get left behind by the kids of parents such as Brind’Amour who have that kind of dough.

Faster, higher, stronger? Sure.

But before all that, the evidence is clear: it’s best you be richer.

email: paul.wiecek@freepress.mb.caTwitter: @PaulWiecek

Paul Wiecek

Reporter (retired)

Paul Wiecek was born and raised in Winnipeg’s North End and delivered the Free Press -- 53 papers, Machray Avenue, between Main and Salter Streets -- long before he was first hired as a Free Press reporter in 1989.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, August 20, 2018 11:43 PM CDT: corrects spelling of Rod Brind’Amour