Crises helped shape modern architecture

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/04/2020 (2057 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

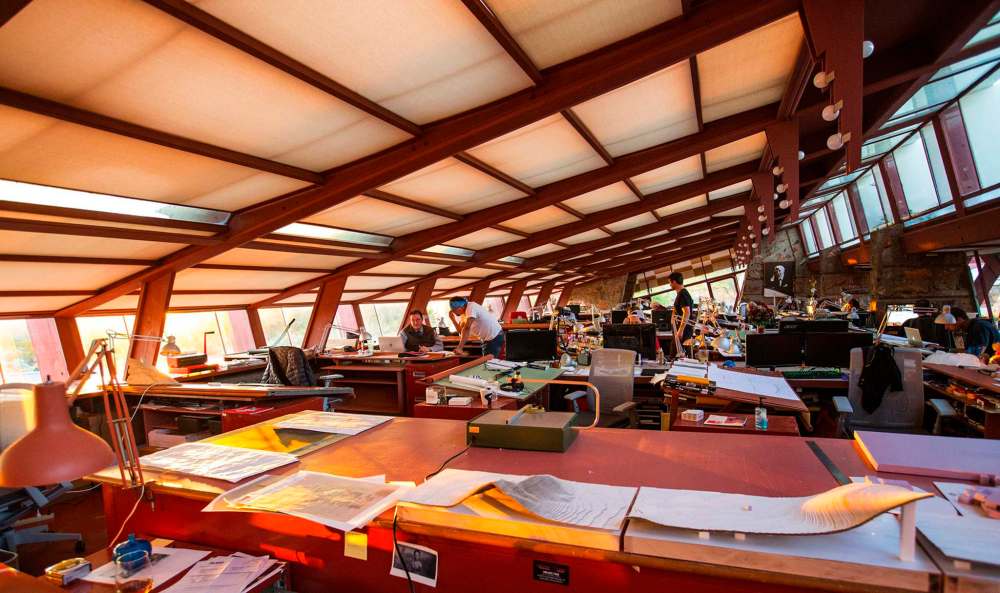

Modern architecture was born out of a global health crisis. With tuberculosis crippling cities in Europe and North America in the early 20th century, gleaming white medical facilities called sanitoriums were designed to provide patients access to sunlight and fresh air, the only known treatment for the disease. This inspired architects to use the same ideas to promote mental and physical health in all new buildings.

Air and light became viewed as a kind of medicine by Modernist architects, and every building type was a kind of health-care facility. From this grew the clean Modernist aesthetic of high ceilings and open volumes, large operable windows, easy-to-clean white surfaces, terraces, and flat roofs — perfect places to sunbathe. The disease had changed the way our world looks.

It is too early to predict how the world will change after we emerge from this pandemic, but as it did in the last century, architecture and design will likely play a central role in the evolution.

As an immediate response to the current crisis, architects can once again look to health-care design for strategies that safeguard against bacteria and virus transmission. These approaches include a return to more non-porous surfaces in high-touch areas, making them easier to clean and sanitize.

Designers can also work with coatings, paints, fabrics, flooring, wall coverings and other building finishes that are antimicrobial, or less prone to allowing bacteria to congregate and multiply. Certain stainless steels, copper and alloys such as bronze or brass are inherently antimicrobial, making them more resistant to pathogen transfer.

“Touchless” technology can help with reducing virus spread by incorporating such things as automatic doors and sinks, voice-activated elevators, hands-free light switches and temperature controls. Less technical touch-reducing solutions include designing washrooms in public buildings so they don’t need doors, and replacing round doorknobs that require a full grasp with lever openers.

This and other high-tech solutions such as medical screening technologies to protect people at airports, sporting events and other large gatherings, will likely see accelerated development and incorporation into everyday architecture in the coming years.

It is unlikely that many buildings will be designed specifically to accommodate the worst-case scenario of a global pandemic, but the COVID-19 outbreak has demonstrated the importance of adaptability in our buildings. Rooms in our homes have suddenly become offices, hospital parkades are now testing centres, and school gymnasiums are becoming temporary intensive care units.

Over the long term, the role of architecture in the new reality of a post-COVID-19 world might take inspiration from the Modernists of a century ago. A renewed focus on the ability for the built environment to affect our physical and mental health would be like preventive medicine to make us stronger and more resilient in times of crisis.

Once again, we can look to health-care design for inspiration. An evolving theory called salutogenic design has been emerging from hospital architecture. Simply put, salutogenic design aims to build structures that make people healthier and happier. Like the Modernist architecture of the 20th century, it returns to the use of sunlight, natural ventilation and views to nature as ways to improve health and well-being.

In health-care settings, studies have shown that access to these elements results in significant reductions in a patient’s average length of stay and need for medication. It has been found to lower stress levels and depression rates and promote faster recoveries.

On some level, these health effects can be realized in all building types if we promote similar design principles — large windows to allow the deep penetration of sunlight, providing views that connect people to their surroundings, and a move away from sealed buildings and mechanical air conditioning to allow natural ventilation with fresh air.

Salutogenic design also promotes mental health through social cohesion and interaction, incorporating welcoming spaces for meeting and human connection, familiar spaces for orientation and comfort, and quiet spaces for focus and restoration.

Architecture has the ability to reshape the world we live in after the COVID-19 pandemic. As architects did a century ago, we can learn from health-care design and incorporate new ideas into our everyday architecture.

Building planning can incorporate the salutogenic approach by encouraging building users to engage in a more active lifestyle. A large central staircase might invite people to avoid the elevator. Showers and change rooms might promote biking or walking. In office space, strategically locating washrooms, copy rooms and lunchrooms can encourage people to make short walks throughout the day.

Building location and exterior design can create interesting and welcoming pedestrian environments that invite people to walk more.

By increasing the opportunities for physical mobility and exercise, such design decisions can help prevent chronic health conditions such as obesity, diabetes and heart disease, improving our immune systems and our ability to meet the challenge of a public crisis.

Architecture has the ability to reshape the world we live in after the COVID-19 pandemic. As architects did a century ago, we can learn from health-care design and incorporate new ideas into our everyday architecture, to promote mental and physical well-being, protect us from pathogen spread, and prepare us for the challenges we will face in the future.

Brent Bellamy is creative director at Number Ten Architectural Group.

Brent Bellamy is senior design architect for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.