Province’s plan to protect students from predators falls short of the mark

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/11/2022 (1117 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The problem with Manitoba’s plan to crack down on teachers who prey on children in schools is it excludes other staff and volunteers who work in the education system.

In its throne speech Tuesday, the Stefanson government announced plans to introduce legislation to create a teacher registry and an independent body to investigate teacher misconduct. The move is being praised by some child-protection advocates as an effective tool to fight child sexual abuse in schools. But does it go far enough?

When you consider that teachers are not the only ones who have access to children in schools, focusing solely on that category of personnel may be falling short of what’s really needed.

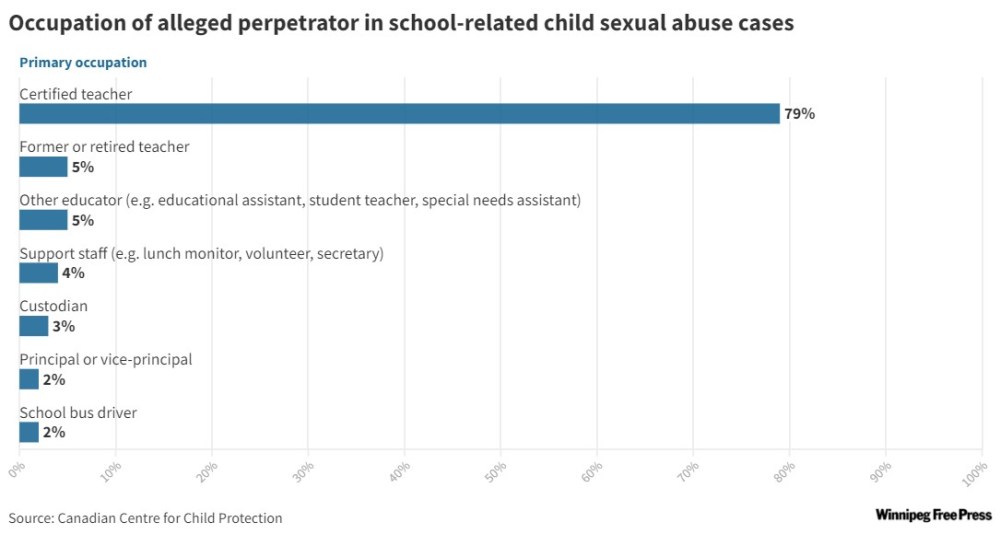

A 2018 report by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection found the majority of perpetrators in sexual offence cases against children in schools were teachers. But they weren’t the only offenders.

Of the 750 sexual offences the organization documented across Canada between 1997 and 2017, certified teachers were the offenders in 86 per cent of cases. However, the study (which doesn’t include all cases of abuse against children in schools because there’s significant under-reporting across the country) identified many other offenders who had the same, or more, access to students. (Read the full report)

The report found other educators, including educational assistants, student teachers and special-needs assistants, made up five per cent of offenders. Support staff, including lunch monitors, volunteers and secretaries, represented four per cent of offenders. Custodians were the perpetrators in three per cent of cases and school bus drivers made up two per cent. Under Manitoba’s proposed legislation, those staff and volunteers would go undetected.

Manitoba currently operates under a secretive system in which allegations of “teacher misconduct” are investigated by either the teachers’ union (the Manitoba Teachers’ Society), school divisions, or both. The results of those investigations are usually kept under wraps unless they result in criminal charges that may become public through the court system.

The case of Kelsey McKay, who taught phys-ed and coached football at Churchill High School and Vincent Massey Collegiate, is an example of a teacher who, for years, stayed under the radar until he was charged criminally with offences related to the exploitation and sexual abuse of students. He was placed on unpaid leave in April.

Not all cases of abuse rise to criminal behaviour. A teacher who sends inappropriate texts or emails to students, for example, may not trigger a police investigation. However, such actions, which can lead to worse behaviour, should be reported and investigated.

Manitoba’s plan is to create an independent body to probe those types of allegations (and others) and establish a public registry. Trouble is, the plan covers only teachers.

“We will be creating both a teacher registry and an independent body to improve accountability and transparency related to educator misconduct in K-12 schools,” the throne speech said.

If the goal is to protect children from predators, an investigative body and a public registry should apply to everyone who works in school settings.

That means non-teacher staff and volunteers who prey on students in schools would go undetected. If the goal is to protect children from predators, an investigative body and a public registry should apply to everyone who works in school settings.

The devil will be in the details when it comes to the effectiveness of Manitoba’s proposed model.

Questions about transparency have already been raised: Education Minister Wayne Ewasko said this week he could not guarantee the proposed registry would include details of disciplinary action against offending teachers (as it does in some other provinces, such as Ontario).

Isn’t that the whole point of a teacher registry, to make findings public so parents and others can keep track of offenders?

If Manitoba is serious about protecting children against sexual predators in schools, it should create an independent body to investigate complaints against all personnel, not just teachers. If it wants to protect kids more broadly, it should consider expanding that oversight to other institutions where staff and volunteers have access to children, such as child-care centres and other early childhood facilities.

Predators lurk in dark places. The province needs to shine the light as brightly and as widely as possible.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.