Vandalism is in the eye of the beholder Destruction of statues connected to actual violence visited on Indigenous people

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/07/2021 (1619 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Five years ago, a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous volunteers in Manitoba got together to bring attention to an incredible wrong.

At the Manitoba legislature, the group pointed out, there was no statue commemorating First Nations in the province. Virtually everyone else, including the Métis nation (honoured in 1973 with a statue of Louis Riel), is recognized.

In the seat of Manitoba’s government and at the heart of Treaty 1, it is as if First Nations don’t exist.

Frankly, there is no Manitoba, no treaties and no legislature without First Nations, so the committee got to work, convincing provincial decision-makers to let one be built in 2020.

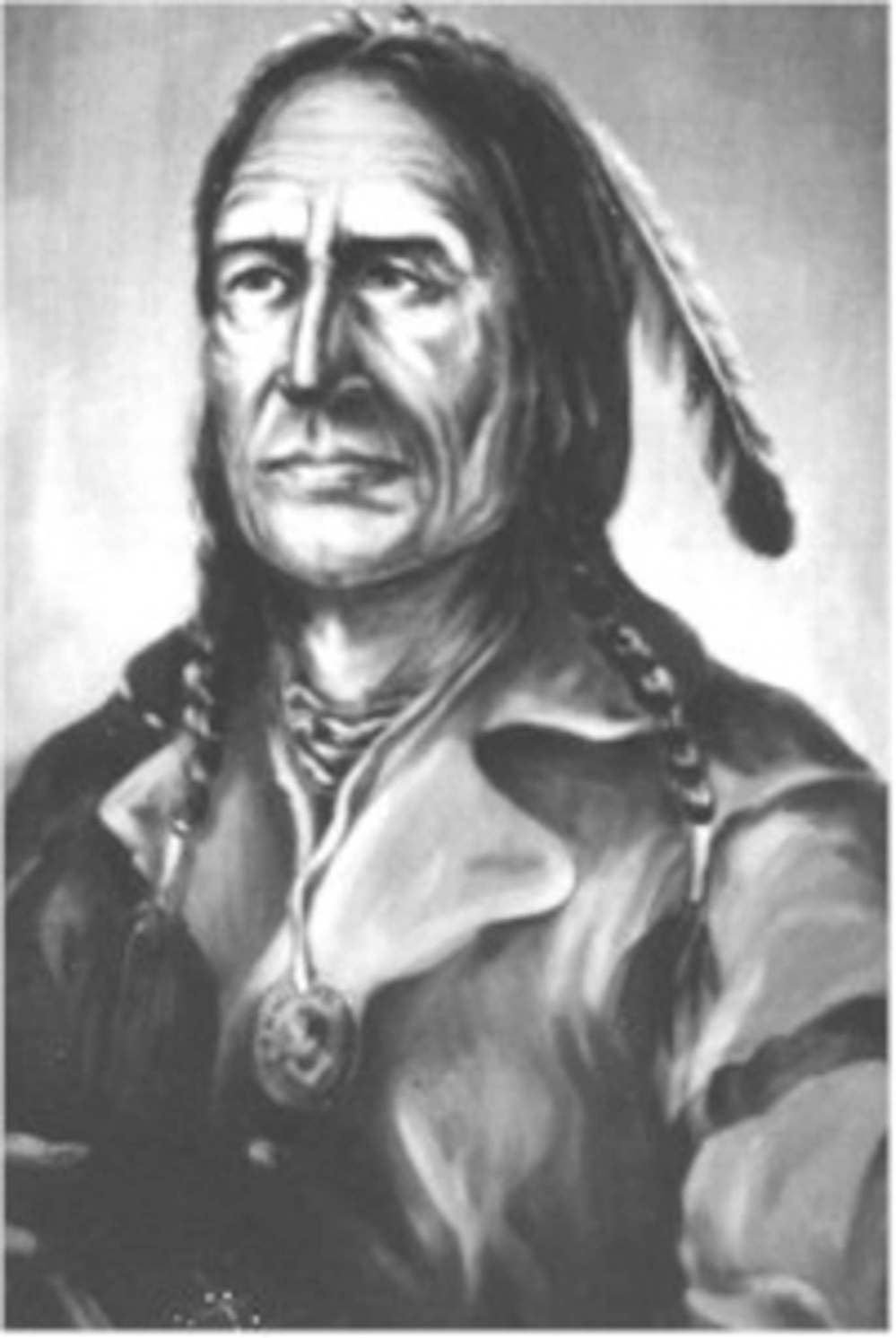

It was determined that a statue of Chief Peguis, best known for negotiating Manitoba’s first treaty in 1817 and welcoming settlers into this territory, would appear once money had been raised and a site found.

“It will fill a great void,” declared organizing committee co-chair Bill Shead, promising an appearance by 2024.

On Canada Day in 2021 — 151 years after Manitoba became a province — a group of citizens had waited long enough.

They created their own monument, toppling a statue of Queen Victoria and covering it with orange shirts and red handprints, commemorating First Nations children who attended Canadian residential schools, many of whom died there.

While around 15 people pulled the statue down with ropes, dozens more covered it and hundreds more chanted “No pride in genocide” in a collective effort.

Some then toppled a statue of Queen Elizabeth — installed in 2010 when the Queen and the late Prince Philip last visited — at nearby Government House.

By the end of Canada Day, the Manitoba legislature had its first statue commemorating First Nations — a reason for this country to celebrate, if you ask me.

Instead, Winnipeg police were looking for “protesters” who committed “vandalism” and Manitoba was the lead story on newspapers and networks across the world.

Many Manitobans suddenly cared about statues, demanding the perpetrators be brought to justice. One ended an email to me with the signature line “reconciliation is now dead.”

Premier Brian Pallister issued a statement, promising prosecution for these “acts of violence.”

Some Indigenous leaders decried the action, while others rightly pointed out thousands of other people participated in other marches that deserve attention.

All seem to have forgotten that vandalism is always based in perspective.

In fact, Winnipeg’s most iconic moment as a city, the overturning of a streetcar during the 1919 General Strike, is commemorated in a sculpture on Main Street. During that act of vandalism, protesters pushed the streetcar off its tracks, shattered its windows, slashed its seats and set it on fire. Two people were killed in clashes with police in what became known as “Bloody Saturday.”

On Canada Day, no one was hurt when the statues came down. In fact, a whole lot of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people across this province felt vindicated. Heard. Seen.

Over the past month, much has been written about children who died at residential schools paid for by the Canadian government and run by churches. Much has also been written about how the attitudes and policies in these schools have led to suffering, poverty and deaths in Indigenous communities today.

This is actual violence we should be concerned about, not the altering of statues.

Thursday’s events were not about erasing history or “cancelling” anyone’s culture. When I woke up this morning, the same old Canada was still here.

If anything, Thursday’s events were statements against the British Crown, which established the laws Canada now uses to justify the theft of First Nations land and resources, and to commit atrocities against children.

These were statements against governments who refuse to change, implement calls for action and justice, and continue to act as though Indigenous lives don’t matter.

These were statements — peaceful, controlled and even artistic — about what inclusion looks like.

For some, Thursday’s actions were disturbing, because the status quo is so powerful and controlling. It’s also evidence of how all change comes with a cost and happens fast when there’s will and desire.

However, true, long-term change comes from building, not destroying, and from methods driven by dialogue, not the destruction of property.

My hope is that Winnipeggers and Manitobans will be as invested in talking about what’s next as they are in statues that mean very little.

My hope is that the remarkable, peaceful and beautiful sea of orange that blanketed this country for one day will never go away and will shape every single day as we go forward.

My hope is that we see beyond our petty, immature perspectives — thrust upon us by this country’s brutal, violent past — and gain the maturity to appreciate that the events in front of our eyes are incredible. We should be patient, kind and adaptable to change.

My hope is that Thursday is a prophecy for tomorrow, with all its attendant complications.

On Thursday, as predicted, we witnessed the most remarkable Canada Day yet — with more yet to come.

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, July 2, 2021 11:06 PM CDT: Corrects CP style of Queen Elizabeth