Manitoba’s finances in for a hard fall Province's rainy day fund not the 'cushion' premier has described it to be

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/03/2020 (1800 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The look on Premier Brian Pallister’s face last week said it all. The scale of the financial disaster that will hit individuals, businesses, not-for-profits and all levels of government this year from the COVID-19 outbreak is almost impossible to measure. But it will be catastrophic.

All budgetary projections unveiled by governments a few weeks ago are now obsolete, as taxation revenues dry up and costs associated with the pandemic escalate. In Manitoba, it means the province will have to borrow at least $5 billion more than planned just to tread water, according to Pallister.

“Let’s be frank, our revenue is down,” Pallister said during a press conference last week. “Not a little, a lot – way down.”

For the province, that means increasing its debt by a record amount this year.

The province had already planned to borrow $5.6 billion in 2020-21 (including Manitoba Hydro), according to this year’s provincial budget. About $3.7 billion of that was to refinance existing debt. Another $2.7 billion was for new cash requirements to pay for operating costs and new capital spending, including infrastructure. The estimated debt repayment for the year was $782 million.

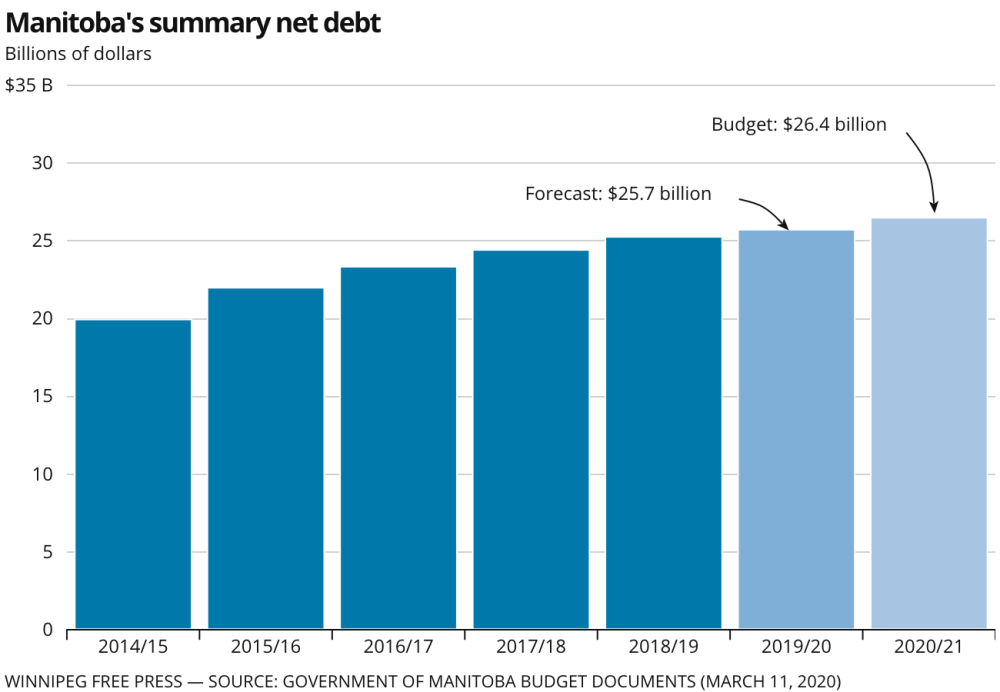

Manitoba’s net summary debt (which doesn’t include Manitoba Hydro) was already expected to rise by $769 million this year to $26.4 billion, according to the budget. Adding another $5 billion to that would see it top a record $31 billion.

The closest the province has come to that kind of one-year jump was in 2011-12, when Manitoba suffered massive flooding along the Assiniboine River. That year, net debt rose $2.45 billion to $19.6 billion.

The projected $5 billion in new debt this year is breathtaking. Most of it is expected to show up as part of the province’s annual deficit. That figure was projected to be $220 million in 2020-21. However, an addendum to this year’s fiscal blueprint suggested it would be higher, depending on how much discretionary spending could be postponed. But even those numbers are now out of date.

If the Pallister government has to borrow an additional $5 billion, mostly to cover lost revenues, Manitoba’s deficit will be in the billions this year, not the hundreds of millions.

Pallister at least had the good sense last week to finally realize his planned PST cut this year should be cancelled.

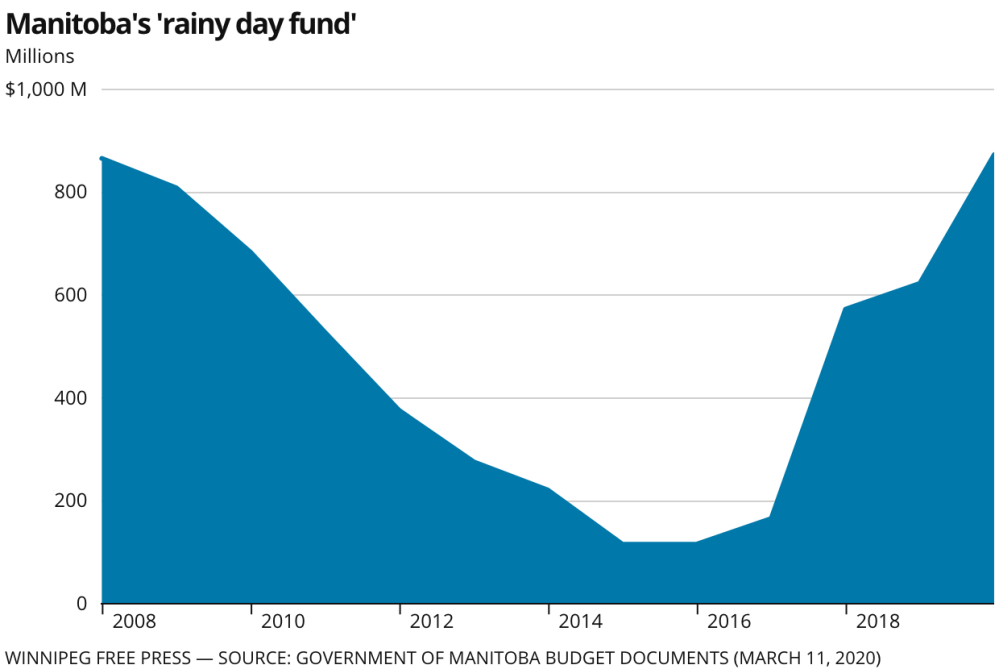

What won’t affect the province’s bottom line is government’s so-called rainy day fund. Pallister has tried to characterize it as a savings account that can be used as revenue in times of need. It isn’t.

The premier said last week the $872-million projected balance in the fund would be depleted in a few months due to the pandemic. He said building up the fund over the past few years has given the province a “cushion” for emergencies like the the COVID-19 outbreak, which is misleading.

“In challenging times, we began to put a little more money away for the future and good thing we did,” said Pallister.

In reality, the fund – officially called the fiscal stabilization account (FSA) – has no effect on the province’s bottom line. Spending cash from the rainy day fund has no bearing on the province’s deficit or surplus. It’s simply cash on hand that all governments maintain to pay immediate bills, like meeting the province’s payroll.

It’s something Manitoba’s auditor general clarified in a December report. Norm Ricard wrote that the fiscal stabilization account “does not impact the financial results of the province as reported in the summary financial statements.”

“The FSA is an account within the government’s ‘operating fund,’” wrote Ricard. “Transfers in are not recorded as an expense of government, nor are transfers out recorded as revenue of government.”

The bigger question now is how much the province will have to borrow next year. Barring a quick economic recovery — which is impossible to predict at this point — the province’s borrowing requirements could be just as bad in 2021-22. If it is, Manitoba’s debt as a percentage of GDP would likely skyrocket to dangerous levels, as it would for most other provinces.That could be mitigated, depending on how much governments do now to help keep businesses and individuals solvent (the Pallister government has so far done very little).

The greater the business failures today (and the deeper the unemployment), the longer this economic crisis will last. The longer it lasts, the more governments will have to borrow in future years just to keep the lights on.

Tom Brodbeck

Columnist

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.