‘Hypothetical’ wage-freeze law faces real-life court test

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/11/2019 (2212 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

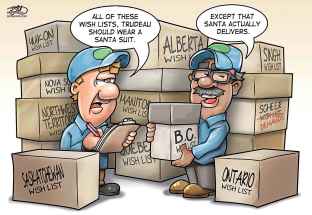

The question of whether the Pallister government has the legal right to impose a wage freeze on public servants should be a straightforward one for the courts to decide.

What will be more complicated to explain is how a court can adjudicate the constitutionality of a bill that hasn’t been proclaimed into law.

Monday was the first day of what’s expected to be a lengthy trial into the legality of Bill 28, the Manitoba government’s controversial Public Sector Sustainability Act. The bill imposes a two-year wage freeze on all public-sector workers, followed by modest increases in the third and fourth year of a contract.

All other aspects of collective agreements are open to negotiation.

A group of Manitoba unions, which has launched a lawsuit against the province, says the wage freeze violates their charter rights to collective bargaining. The province argues since the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled governments can legislate some aspects of collective agreements, they’re on solid legal ground.

The bigger question is: how can the courts rule on a bill that has yet to be proclaimed into law?

It’s a point the province appears eager to argue. In her opening statement, provincial lawyer Heather Leonoff said Bill 28 “is not law” and courts don’t deal with “hypothetical law.” She said the bill may never become law.

Bill 28 was passed by the legislative assembly and received royal assent June 2, 2017. But in order for a bill to become law, it has to be proclaimed. Some are proclaimed upon royal assent, via the lieutenant-governor; others require cabinet approval, which Bill 28 hasn’t received.

There are often valid reasons for such a delay, including the need to draw up regulations. But in the case of Bill 28, the delay appears to be tactical — the Pallister government was trying to avoid the risk of an unfavourable court ruling while still having the bill influence contract talks.

It worked to some degree. Some contracts have been negotiated under the terms of Bill 28, including a new deal for Manitoba doctors earlier this year.

But now the bill is before the courts.

The bigger question is: how can the courts rule on a bill that has yet to be proclaimed into law?

If it’s ruled unconstitutional, the legislated wage freeze is off. However, if the courts see it as a reasonable limit on collective bargaining rights, it will be a major defeat for the union movement.

Whatever Queen’s Bench Justice Joan McKelvey decides will almost certainly be taken to the Manitoba Court of Appeal.

What’s less clear is how the courts can render a decision either way if the bill hasn’t been proclaimed into law. Governments sometimes ask courts to rule on the constitutionality of bills before they’re introduced; this isn’t one of those cases.

It’s not law, as the province argues, but it does have the effect of being law since it can apply retroactively, if and when it’s proclaimed. It doesn’t affect contracts in place prior to the passage of the bill, but it does apply to new contracts that fall within the bill’s “sustainability period.”

If a bargaining unit concludes a new collective agreement and the provisions of Bill 28 are ignored, the bill could apply retroactively if it’s proclaimed at a later date.

It’s a legal rat’s nest.

To complicate matters further, the Pallister government last month introduced an amendment to the Public Service Sustainability Act, which — among other things — would give cabinet more discretion on how the legislation is applied.

Governments sometimes ask courts to rule on the constitutionality of bills before they’re introduced; this isn’t one of those cases.

Under these circumstances, it may be appropriate for the courts to weigh in, even though Bill 28 is officially not law. How else are employers and bargaining units supposed to interpret this legal quagmire?

Imposing a short-term wage freeze on public servants is a reasonable step under the circumstances. The Tories inherited a massive deficit and soaring debt from the previous NDP government, which resulted in three credit rating downgrades. Immediate steps to reverse that trend were critical to the financial well-being of the province.

But refusing to proclaim Bill 28 has caused unnecessary confusion and unfairness for both sides in the collective bargaining process.

It will now be up to the courts to sort out this mess.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.