Candidate transparency law keeps some offences secret

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/08/2019 (2301 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In May, MLAs passed Bill 240 — stating all electoral candidates must disclose publicly if they have been found guilty of crimes committed under the Criminal Code, Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, Income Tax Act, or “any other law related to financial dishonesty.”

Conservative MLA Sarah Guillemard, who sponsored the bill, said: “Voters in Manitoba should be aware of the history of all candidates, so they can make the best decisions possible.” A news release from the PC caucus said the law “would make Manitoba the most improved province in Canada for candidate transparency.”

A candidate must submit disclosures to Elections Manitoba or face a fine up to $10,000 or jail time.

They have until Monday at 1 p.m. to comply. By Friday, approximately 65 per cent of all provincial candidates had submitted disclosure forms, which were posted online by Elections Manitoba. More are to be released Monday.

There are a few surprises: NDP candidate Tom Lindsey (Flin Flon) pleaded guilty to impaired driving in 1977; NDP candidate Wayne Chacun (Riding Mountain) was found guilty of shoplifting and impaired driving in 1987.

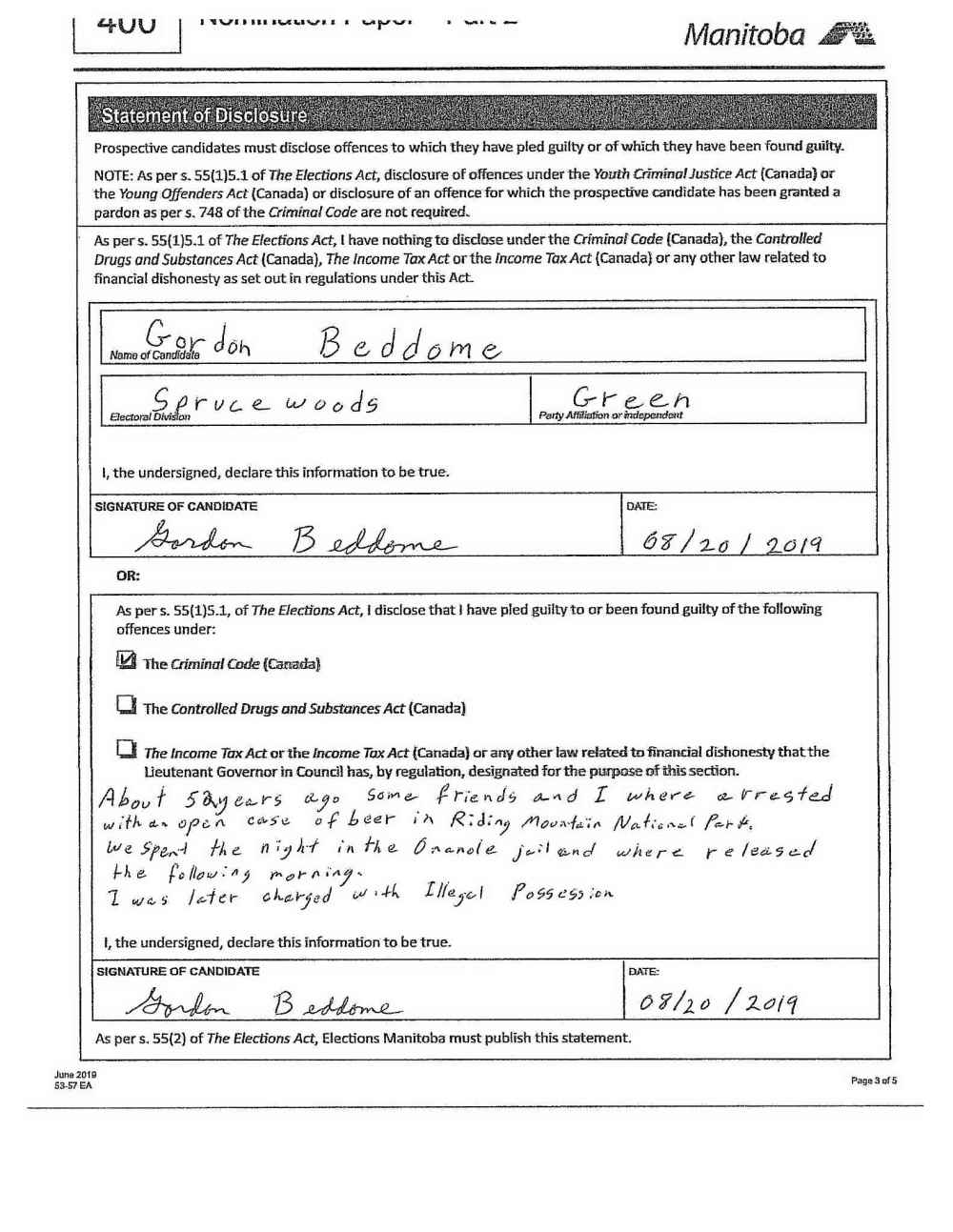

Some disclosures border on silly. Green candidate Gordon Beddome (Spruce Woods) admitted to being “arrested with an open case of beer in Riding Mountain National Park” and spending “the night in the Onanole jail” with friends in 1967 — fifty-two years ago.

Some are unsurprising. Green candidate David Nickarz (Wolseley) was found guilty in 1994 of non-violent civil disobedience while protecting a forest in B.C.

One, however, stuck out.

NDP candidate Joe McKellep (Assiniboia) was found guilty in 1998 of assault causing bodily harm, and violating the conditions of parole in 1999.

McKellep is one of the rising Indigenous political stars of the NDP. He is Métis and Cree, originally from The Pas, and has a strong record working in restorative justice with Indigenous youth.

In an interview, he said it was a “one-time bar fight” when he was 25, and has “regretted for the rest of his life.” He had no prior charges nor has any since.

As part of his guilty plea, he agreed to pay restitution and apologize to the man he assaulted.

McKellep, however, paid a much steeper personal price. At the time, he was an auxiliary RCMP constable accepted into the academy. He got into a bar fight, was charged, and lost his spot.

That night “changed my life,” he said. For months, he was angry and disappointed in himself. He violated his parole-imposed curfew one night during this time and had to pay a fine of $400.

Two years later, McKellep took over his father’s courier business and eventually entered an Indigenous management training program. He got a job with Manitoba Justice in 2007.

For a decade, he worked with Indigenous communities, telling his story to youth: “A mistake doesn’t define you.” He worked up the ranks to become a manager in Winnipeg.

In 2016, he ran for the NDP in the Assiniboia riding. He disclosed the assault charge during the vetting process and was deemed suitable. He did well, receiving 28 per cent of the vote, placing second.

The question is whether mistakes made decades ago — many atoned for — will influence voters.

This is the problem with the legislation. In an effort to promote transparency, there is only guilt and judgement, and no room for rehabilitation. In a world in which Indigenous peoples, the disenfranchised and those in poverty struggle, who has the most to disclose?

The legislation doesn’t require disclosures for other violations that illustrate important character, judgement, and breaches of trust violations. Professional misconduct, for example, (disbarment for lawyers, malpractice for doctors, dishonesty in accountants) is not included.

The legislation does not require former Tory justice minister and deputy premier Heather Stefanson to disclose she was suspended for seven months in 1999 by the Manitoba district council of the former Investment Dealers Association of Canada for “failure to meet educational requirements.”

Stefanson, who was in charge of deciding hundreds of cases of professional misconduct as justice minister, was found to have made 34 inappropriate trades while working as an investment adviser at Wellington West Capital Inc.

A spokesperson for the PC party issued a statement to the Free Press which said Stefanson has been “fully transparent about the incident” and couldn’t keep up her credentials because she had to “help care for her mother.” The spokesperson said: “during this time, a trade went through on a family account” which “she accepted responsibility for the error.”

When asked about the 33 other cited violations, there was no response.

Bill 240 seems designed to protect one group of people (white colar professionals) and punish another (blue collar, working-class activists).

In the end, it might be the most transparent discovery of all.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.