Smallpox epidemic left massive Indigenous burial ground under Winnipeg’s downtown

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/10/2018 (2630 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 1781 a smallpox epidemic ravaged communities across the plains, in what is now southern Manitoba. The decimating sickness came with a death rate as high as 90 per cent.

Near what is now called The Forks resided 800 lodges of Indigenous peoples, a community of approximately 5,000. Most were Cree, but among them were likely Nakota and Dakota (also known as Assiniboine), who travelled along the Assiniboine River and also lived here. Anishinaabeg (also known as Ojibwa) also frequented the area, but generally came to hunt and trade and afterwards return to their eastern territories.

These Indigenous nations lived, travelled and traded here for at least 6,000 years.

The French were newcomers in the area, residing nearby at Fort Rouge. The British-owned Hudson’s Bay Company arrived in the 1770s. Both were invested in the fur trade and had entered the politics of this space, following the guidance of Indigenous leadership that was firmly in place. Europeans had entered a well established civilization.

Until the sickness changed everything.

The smallpox epidemic arrived in the autumn, killing hundreds in its wake. By 1784, more than 1,000 people were dead. They were buried quickly, left behind by communities fleeing the epidemic and travelling north and west.

Recorders to the area could not help but comment on the tremendous number of graves here. In 1800, the fur trader Alexander Henry described “old graves, of which there are many, this spot having been a place of great resort for the natives.” In 1808, surveyor Peter Fidler commented in his journal about “graves on E. side by river at mouth.”

Fifty years later, fur trader Edwin Denig described the graves as located in “a mound near the mouth of the Assiniboine River embracing an area of several hundred yards in circumference and ten to twenty feet high, being the cemetery of nearly an entire camp of 230 lodges who died of the infection.”

That’s 1,200 dead, according to Denig, the mound located in “the heart of the city of Winnipeg” on “the north bank of the river.”

More on this in a moment.

The impact of the epidemic cannot be understated. It resulted in Anishinaabeg moving permanently into Manitoba, often to support southern Cree communities. One migrating group was led by Peguis, who settled with a community at Nebowesebe (Dead River, now known as Netley Creek). Peguis would eventually ascend to leadership amongst Red River Indigenous communities and negotiate European settlement with Lord Selkirk on the Red River in 1817.

For years, these and other Indigenous nations had been joining with Europeans to create the descendants of the Métis Nation. In 1814, the Métis Nation was fully realized with the Battle of Seven Oaks, expanding throughout the Red River and culminating into Manitoba’s provisional government in 1870 and the entry of Manitoba into Confederation.

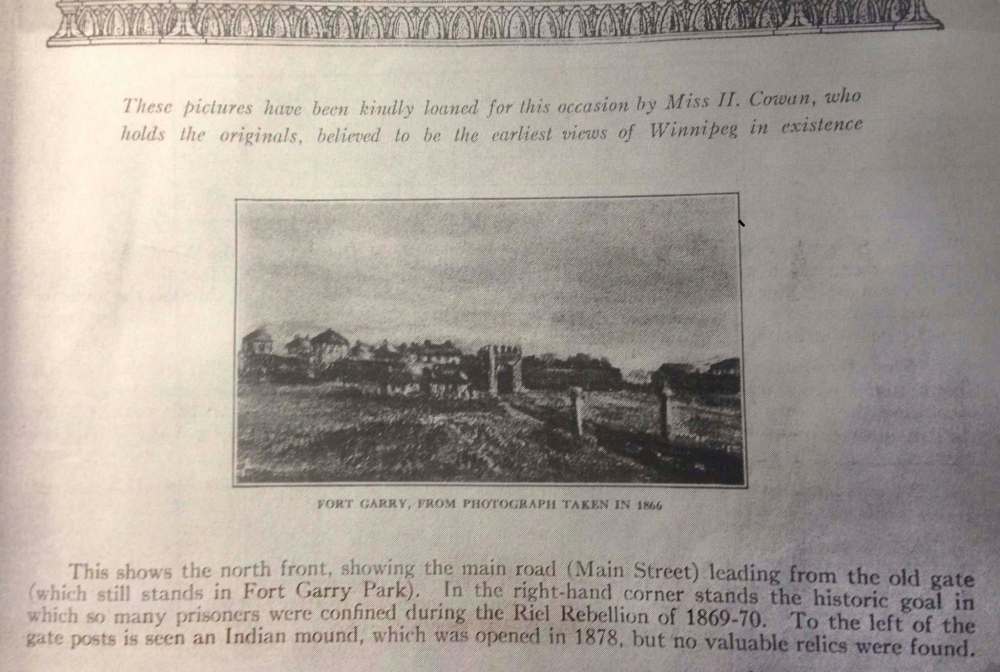

Due to the epidemic the French and, later, the North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company would expand into the region, eventually resulting in conflicts and bilingualism in Manitoba. A large part of this occurred after the companies amalgamated and Lower Fort Garry and Upper Fort Garry were built in the 1830s. Located on what is now Broadway and Main Street, Upper Fort Garry is the foundation of the city of Winnipeg.

But thousands of years of Indigenous presence don’t simply disappear.

As Winnipeg emerged, so did its history; much of it buried under high-rise buildings and hotels.

Which bring us back to Denig’s “mound.”

The question of its location has been the subject of much debate, as evidence piled up via the discovery of myriad Indigenous gravesites throughout the downtown.

An 1871 plan of Upper Fort Garry by J.S. Dennis noted an “Indian burying ground” near the southeast corner of Main and Water streets, now William Stephenson Way.

In the 1920s, historian Charles Bell claimed an “extensive Indian grave yard” was situated on what is now the east side of Main Street between Graham and York avenues.

You get the point. From 1875-1922, 11 more sites were uncovered with locations on Fort Street and St. Mary, Portage and Wesley avenues.

Each of these point to a huge, extensive burial site of Indigenous peoples, literally underneath the feet of Winnipeggers.

Last week, retired archeologist Leo Pettipas called me. We spent several days raking through archives, books and reports in an effort to pinpoint the infamous mound.

I should have known where I would find my answer.

In a story dated Oct. 11, 1875 in the Manitoba Free Press, we found the following: “While excavating on the mound opposite the northern gate of Fort Garry, October 9, 1875, it was discovered that the mound was an old Indian burial place. Quantities of very large human bones, skulls, etc. were unearthed and carried off by curiosity seekers.”

Leo thinks the paper meant “very large quantities of human bones” instead of “quantities of very large human bones.” I agree with him.

Further research produced a blurry 1866 photo of the mound, just in front of the north gate of the Upper Fort Garry settlement, in the book Souvenir of Winnipeg’s Jubilee, 1874-1924. In it, the description says that within a short distance from the Fort is “an Indian mound, which was opened in 1878, but no valuable relics were found.”

I’ve since found more references to the mound being excavated and searched by grave robbers from 1840-60. Later, traffic at the site increased as Broadway was built, streetcar tracks were laid, and, finally, a gas station was constructed at the corner of the Upper Fort Garry site in 1925.

The former mound site therefore begins either at the front of that gas station, Broadway or across the street where the Fort Garry Court (also called Strathcona Block) was built in 1902 and demolished in a 1976 fire. An insurance company building stands there now.

The burial mound “several hundred yards in circumference” may encompass not just the previously discovered sites, but maybe others, as well. Several hundred yards is, after all, a few football fields in size.

In 1870, for example, soldier Sam Steele was walking south from Upper Fort Garry towards the Red River (the former site of Fort Gibraltar) and found “several much decayed human bones and one skull close to the water’s edge, which had apparently rolled down from near the general ground level of the bank through undermining by the heavy spring flood.”

Steele believed the remains to be those described by Alexander Henry 70 years earlier.

If true, much of downtown Winnipeg — from Portage and Main to Broadway — is the site of a massive Indigenous burial mound. Maybe more than one.

Let that sit for a moment. Look around. See it.

Our history is here, and these voices echo into today.

How we hear, honour and, hopefully, one day memorialize our long-departed relatives — whom we are all here as a result of — is now up to us.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, October 3, 2018 12:12 PM CDT: fixes typo