Blossom’s brotherhood The little park has a different name and the old elm tree is gone, but for the River Heights boys who forged lifelong friendships there 65 years ago, the memories never fade

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/08/2018 (2660 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If Dan Allen had a dollar for every ball that he threw in this park, he says, he’d be a rich man today. A dollar for every ball thrown, or a dollar for every story that he heard under that old elm tree; it works either way.

The old tree isn’t here anymore, in this little park on Wellington Crescent. It died back in the 1990s, so the city chopped it down and hauled it off. Yet the stories that once flourished under its branches, Allen never forgot.

It wasn’t the football that made this place special, he says, so much as the bonds they forged playing it.

So this is a story about sports. It’s an oral history of the community life that once animated this part of River Heights. It is also a story about 65 years of friendship, soon to be reunited. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

First, to understand what kept the Blossom Boys together, you have to start at the same place they did.

Today, it is Andrew Currie Park, named after the iconic CFL executive whose house overlooked the site. At the time, it was still known as Blossom Park, a wedge of green bordered by trees, a railroad track running beside it.

The park was not an ideal football field. It was a little short, and one end zone was wider than the other, so woe to the team that had to defend it. Yet in 1953, it was the perfect spot for a group of teens to stake their athletic claim.

There were 34 of them in all, River Heights kids from what was then the humbler side of the tracks. In time, they grew up to become doctors and farmers; their ranks included journalists, artists and even sports Hall of Famers.

Brier champion and longtime curling broadcaster Ray Turnbull was a Blossom Boy. So was former MJHL star Cliff Pennington: he played 101 NHL games, mostly with Boston, and took Olympic silver with the 1960 national team.In the mid-1950s, they were just a gaggle of teens, hunting for fun in a neighbourhood that, at the time, felt more like a small town. Older kids shooed them away from other spots, but Blossom Park was open for playing.

Yet in the mid-1950s, they were just a gaggle of teens, hunting for fun in a neighbourhood that, at the time, felt more like a small town. Older kids shooed them away from other spots, but Blossom Park was open for playing.

It wasn’t just football. The Blossom Boys, as they came to be called, played every sport. In summer, there was slo-pitch and ball hockey; in winter, they crossed the frozen Assiniboine to slide down a ski jump on the north bank.

Everything they did was competitive, Allen says. After school, they’d cluster in front of an Academy Road drugstore, and challenge each other to a so-called Sidewalk Olympics — long jumps on concrete, that sort of thing.

Those were the kind of hijinks that give parents ulcers; mercifully, no parents were ever around to see.

That was the beauty of it, Allen thinks. They were young and vital, and mostly left to their own devices. They refereed their own games. And it was at Blossom Park where most of that youthful energy spread its wings.

As the years turned, the Boys’ games became well-known. They developed season highlights of their own: the most famous of those was the annual Toilet Bowl on Jan. 1, the only game they played with full contact.

They were all good athletes, though not all of them great. That didn’t matter when they played.This month, to mark their 65th anniversary, the remaining Blossom Boys will hold a big reunion, and this time, it might really be the last.

“Nobody had to tell anybody they were good,” Allen says. “If you didn’t have a good game, well, then, be better the next game. But you were equal. You might have been picked last, but they were still going to throw the ball to you.”

After each game, they would stretch out under a gnarled old elm and swap tales of dubious veracity, tales about friends or teachers or tomfoolery that grew longer with each telling. They’d spend hours that way, in the shade.

That’s what drew them together — and it’s what kept them coming back, long after they’d grown up.

In 1983, the Boys — then in their mid-40s — marked their 30th anniversary with a splashy reunion. It made the news: iconic Manitoba sportswriter Vic Grant wrote a gung-ho column about the Boys’ legacy for a local paper.

At the end of the column, Grant noted that the reunion might be their last. That was 35 years ago.

“We lasted longer than we thought,” Allen says, with a hearty laugh.

Because the years turned, and the Boys kept going strong. They had another reunion in 1995, two years before the city renamed the park; the Boys tried to get the old Blossom Park sign, but it vanished after it was taken down.

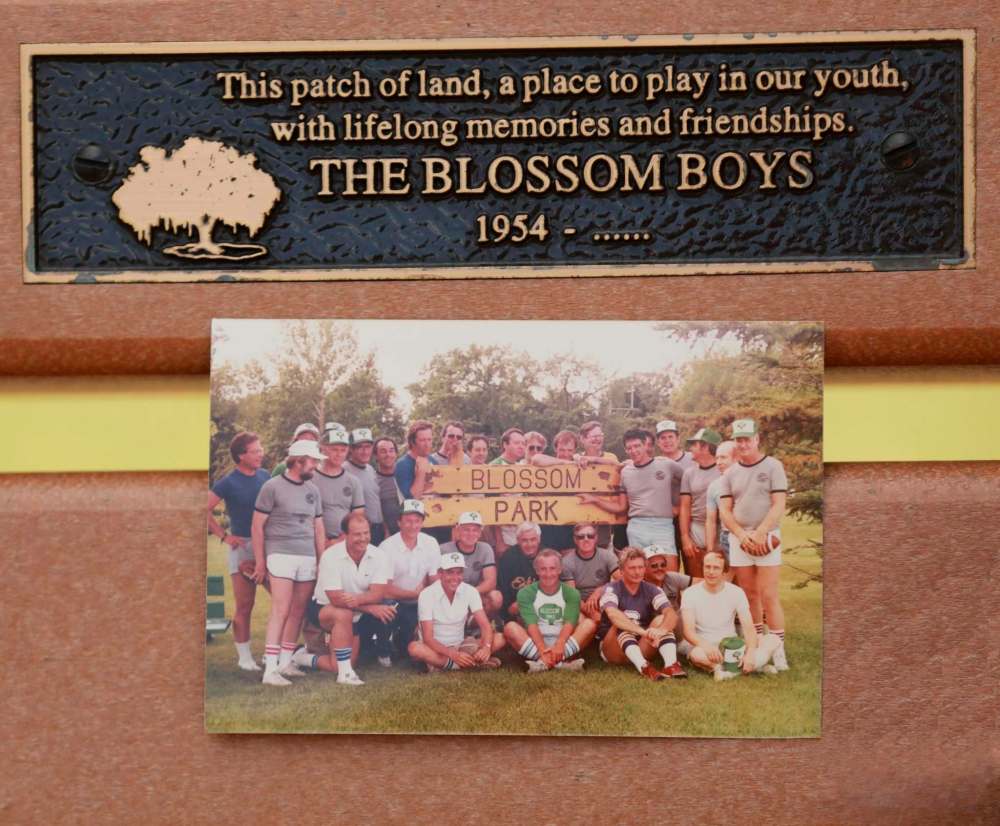

Oh well. To commemorate the park, they donated a bench, engraved with a message: “This patch of land, a place to play in our youth, with lifelong memories and friendships.” They deliberately left the dates open-ended.

Now, though, their time to remember this park together is waning. The past couple of years have been hard: they lost Mark Young in late 2016. Turnbull died of leukemia last October, followed by Michael Burstow in December. Then Barrie Plews, just this summer.

Over the years, they’d lost other Blossom Boys. But these came in a rush, one after the other.

“We’re not bulletproof anymore,” Allen says. “When I had to do the eulogy for Barrie, I thought… he was the glue. The sports was immaterial. The sports are the things that we did, but the most important part is the memories.”

So that cemented the decision: one more hurrah then, one more for sure. This month, to mark their 65th anniversary, the remaining Blossom Boys will hold a big reunion, and this time, it might really be the last.

What happens at a reunion? In past years, they played a little hockey, or knocked some golf balls around. This year, with most of the Boys pushing 80 years, the prospect of some of those activities is… slightly daunting.The last night of the reunion, they keep for themselves. On the 13th, they’ll meet for a banquet– just the Boys, no one else — and reaffirm those bonds they built, as young ruffians on the hunt for places to play.

“We’re running out of things to do,” Allen says with a laugh. “Maybe we could lawn bowl.”

Most of the reunion is just for old friends. But on Sept. 12, there will be a free evening social at Corydon Community Centre’s Sir John Franklin site. Everyone is welcome to attend; past reunions have drawn up to 200 people.

It’s not just the Boys themselves, Allen says. They’re still in touch. But they sure would like to see other familiar faces from the old neighbourhood and other long-ago friends; their bonds spanned out beyond just their group.

Still, the last night of the reunion, they keep for themselves. On the 13th, they’ll meet for a banquet — just the Boys, no one else — and reaffirm those bonds they built, as young ruffians on the hunt for places to play.

That night, they’ll be together again. A slice of Winnipeg history, never to be found in a museum, etched in living memories of tales that grew longer and trees that sheltered them. When all is said and done, what else matters?

“If you’ve got a group of friends, stay with them,” Allen says. “Don’t forget about them. It’s not what you take out of this world, it’s what you leave in it.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.