‘A lifetime of healing’ For those who have grown up into a life of crime and incarceration, long-term change requires compassion, cultural reconnection, sustained addictions rehabilitation and healthy role models

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/01/2023 (1073 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There’s no issue facing Winnipeg that draws as much attention, that sparks as many headlines and as much fear and anger and frustration, as crime. It’s in the news every day. It’s the focus of nearly every election campaign. Residents worry about it, some politicians pledge to get tough on it and social media bristles with arguments about how to solve it.

In all these public discussions, one set of voices is often absent: those of people with criminal records.

Yet their experience and knowledge are critically valuable. To lower crime we must first understand it; and to understand it, we have to name it. Crime isn’t a mysterious force. It doesn’t just happen. Crime is an action, taken by people. So if we want to reduce crime rates, the next most logical question is simple: why do people take those actions?

Nobody understands that path better than those who’ve walked it, and earned their insight into why crime happens.

Over the last few weeks, the Free Press spoke to four men and one woman who have an extensive history with the criminal justice system. We asked each the same questions, inviting them to share their story, reflect on what factors were the most helpful to them in breaking the cycle and offer their ideas for the most important investments to lower crime rates.

Their stories were unique, but also instructively similar. Most described childhoods stricken by poverty, abuse and massive intergenerational trauma; two of the folks we spoke to volunteered that they’d survived childhood sexual abuse. Most grew up in families that struggled with addiction, and all five began to use drugs or alcohol heavily as children.

To lower crime we must first understand it; and to understand it, we have to name it. Crime isn’t a mysterious force. It doesn’t just happen. Crime is an action, taken by people.

They described how that trauma compounded, exacerbated by a lack of recovery supports and basic material resources.

Above all, most described how their entry to criminal activity came from a deeply human place: a desire for community and belonging. Once, they were all just kids looking to love and be loved, and found ways they could help their peer group get the things they wanted or needed. That instinct to build community can thrive, given a healthy place to grow.

There’s a lot of hope in their stories. They spoke about the transformational power of connecting with culture and in creating stronger support networks. For some, a key positive turning point was a program they accessed while incarcerated; several cited receiving addictions treatment at the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre as a life-changing experience.

And for Josephine Harper, what helped most was meeting just one person who believed in her, and wouldn’t give up.

All five are now on a healing path, and are working to help others reach the same. Terrence Morin is going to school, and working in peer support at Bruce Oake. So is knowledge-keeper Tim Barron. Harper is studying to become an addictions support worker, while Glen Hondz is volunteering with several community efforts, as is Jeremy Raven.

These are their perspectives. Interviews have been condensed for length, clarity and focus.

Tim Barron, 38

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Tim Barron (New Grizzly Bear Man)

Where did you grow up?

We moved around a lot. That caused a lot of hurt growing up, because I wanted to make friends at school but then we would move from one neighbourhood to another when I was just starting to get to know these other children. I remember that. So I grew up mostly around the North End, then we moved to the Polo Park neighbourhood.

How did you first come into contact with the justice system?

Seeing and hearing everything that I went through as a child from my father and my mother, seeing them drinking, partying, seeing my father sell drugs, and all that activity growing up. Then my cousins, I wanted to be like my cousins. My cousin was an active gang member. I wanted to be bad, just like him.

When I was 15 years old I started drinking. The first time I drank I got in trouble and I went to the Manitoba Youth Centre. It just spiraled from there and kept on going. I was pretty much in and out. I was only in the Youth Centre that one time until I was 18. After that it was pretty much (incarceration) every year, up until I sobered up at 35.

I was a follower. I followed everybody. I wanted to fit in with these other people, with my friends. I didn’t have “me.” I didn’t have supports growing up, like positive role models. If I would have had a cousin or a family member that was involved in a healthy way of living, I think it could have gone a different direction. But I didn’t have that.

I remember growing up saying “I don’t want to be like my dad,” but I ended up growing up just like him.

What most helped you make positive changes in your life?

If I would have had a cousin or a family member that was involved in a healthy way of living, I think it could have gone a different direction. But I didn’t have that.–Tim Barron

When I sobered up. I ended up going to self-help groups, and then I ended up getting involved in my culture. That’s what helped me a lot, is my own culture and ceremonies. That helped me so much. I met my dad’s family in Sagkeeng and I got heavily involved in it, and I just continue to stay involved in it.

No, I didn’t (have access to culture growing up). That’s all from intergenerational trauma. My grandma and my grandpa are residential school survivors and my mom was a day school survivor. We were disconnected from our culture… I didn’t have the right connections early on, but now I do. For ceremony stuff, you have to know people to get involved in it.

I do sweat lodges today. I’m a sun dancer, and I teach men how to sing on the big drum. I reconnect them to their culture, to their communities, and just as much as I’m helping them, it helps me to stay on that good path. I try to think of others more than myself. I thought about myself all my life, and I thought I knew what was best for me. But I really didn’t.

So it has helped me a lot. I have purpose today, and that’s being a spiritual helper to help other men and women so they can find themselves and their purpose in life. What I love to do is help other people to walk on a good road.

When you look at the city now, what do you see as the main factors influencing crime rates?

I see a lot of the youth, and they’re growing up the same way I grew up.–Tim Barron

Just lack of resources and a lack of strong healthy men that are trying to help people. We need more people like us out there. There are self-help groups, but it doesn’t really work for everybody. Ceremony doesn’t really work for everybody. But there’s other resources we can do to show these young men there’s a better way of living.

Because I see a lot of the youth, and they’re growing up the same way I grew up. For myself there’s the bigger me here today, and if I saw my little self I’d say, “you’re going to come with me to ceremony.” I might have to say it with authority, in a good way, not scary, just a kind type of authority. And I’d get that little boy to come with me. He would come.

What are the most important things we as a community, city and province can do to reduce crime?

There’s resources out there, but there’s not enough. A lot of these little kids want to be rappers nowadays. If there was stuff like that going, a building where you can come make music but there can also be staff on site who can monitor them and see how they’re doing. Maybe we can integrate culture and get them to smudge before they start their music sessions.

There’s a couple places like that, but it needs to be something bigger, like a big safe space for them to go. It would have to be a drop-in centre, where you can just come there. Then there would be cultural workers, or any kind of worker. Just someone healthy… We don’t want to be causing lateral violence to these youth. We want to end that stuff, or try to.

For (Indigenous people) it’s a lot of intergenerational trauma. This is what I want them to understand. We were born with it, and trauma equals addiction, and addiction is like we’re chasing it.–Tim Barron

For these youth that are going in and out of the Youth Centre and in and out of jail, they should be having sessions or classes that are about living a good life. Most people when they go to jail, you’re going in there trying to be a better criminal. There’s not really any resources for these youth. They should be making more stuff to show them there’s a better way of living.

What do you wish people in Winnipeg knew about people with criminal records?

For (Indigenous people) it’s a lot of intergenerational trauma. This is what I want them to understand. We were born with it, and trauma equals addiction, and addiction is like we’re chasing it. We’re doing pretty much anything we can. So that’s going into a store and stealing whatever, just to get our next fix.

I really want them to know we need to start breaking that cycle for these youth. Then I try to teach these guys. Even though we make mistakes sometimes, and we go back into that, we’re still learning. It’s a lifetime of healing. We got to continue to heal for the rest of our lives. It’s about having supports too.

Glen Hondz, 38

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Glen Hondz Swirling Wind Eagle Clan

Where did you grow up?

I grew up all over the city, mostly the North End and East Kildonan. We moved around a lot. My dad didn’t keep a place more than a year, so I really couldn’t make friends. I was always hanging around with the wrong crowd, did stuff with gangs. My dad made sure we had a roof over our head and we always had food, but we were in the middle of poverty.

There was a lot of drinking around that home. A lot of fighting all the time. We were living in the North End, on Cathedral. A lot of different people going in and out. My dad didn’t know, but I was also getting abused by the people who were coming to the house. So I started running away from home.

How did you first come into contact with the justice system?

I started running away from home, hanging around with older gang members. I was eight years old, that’s how young I started. I used to think it was OK to break into houses, to fight people. I’d seen a lot of violence growing up, especially towards women.

At that age I couldn’t get charged. So I felt like I could do what I want. I was starting fires, burning down houses. I was doing what I was told by the older gang members. I had to do it. That’s what I used to think respect was, was doing what I was told. Proving myself to them, earning my respect that way.

I used to think it was normal. Seeing my family drink, fight, hurting women, fighting friends… It was all I knew.–Glen Hondz

That went on for years. I kept running back to this area, hanging around my friends still, getting in trouble, stealing, doing crimes. I was jacking cars with my friends at an early age, 14. Then they passed that law where kids could get charged as an adult, and I started getting (adult) charges.

I used to think it was normal. Seeing my family drink, fight, hurting women, fighting friends — it was all normal to me. There would be weeks that would be good, then weeks that wouldn’t be good. I was trying to follow my two cousins who were also in gangs. I thought that was cool. I wanted to be like them, I looked up to them.

It was all I knew, until I had a brother-in-law, he followed culture. He’s the one who got me off the street after I got charged with armed robbery (at 17). He said “you’re coming with me, I’ll try to show you a better way.” I was still too stubborn to listen, but I did good. I went to work every day. Nothing really bad happened during those times.

So I thought I was a functioning alcoholic, from 17 all the way up to my 30s.

I didn’t even notice I was bringing all this stuff into my relationship that I’d seen from my dad and my mom.–Glen Hondz

After my brother-in-law took his life, that’s when things went downhill for me. I started coming back and hanging around gang areas. I started doing meth and shooting (up), and I lost my way. I had really good jobs, I had benefits, I had a three-bedroom house with my ex. We were doing good, then we started drinking heavily, then we started fighting.

I didn’t even notice I was bringing all this stuff into my relationship that I’d seen from my dad and my mom.

What most helped you make positive changes in your life?

It took my incarceration. I couldn’t get into any beds for detox, they were all full. So I went and robbed a store as a cry for help. This was 2018… I thought maybe if I just do a simple crime, I’ll do some time and get healthy that way. That’s exactly what happened. I did that crime and waited for the cops… I went to Rockwood (Institution).

I was going to get involved in the gangs, but one of the higher-up guys said “maybe you should forget about this stuff. You’re getting old, man.” He’s a younger guy than me but I looked up to him. He said, “you should think about going to Crane River (O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi Healing Lodge, a corrections-affiliated facility located about 300 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg). Talk to the elder here, learn about your culture. Start going to sweats, pipe ceremonies.”

I thought about it, and thought, “maybe you’re right, man. Maybe it’s time I make a change.” That’s exactly what I did. I told them about my history, that I want to be spiritual and follow my culture. I talked to the elder there, and he says “we’ll put in an application.” Next thing you know I got accepted… So I got shipped out to Crane River.

That was the best place for me, the best decision I ever made. As soon as I got there I was welcomed… I showed them how hard I could work, how involved I wanted to be in the culture. Next thing you know I’m drumming and going to sweats, I’m working hard every day. I’m out in the bush learning the bush life, snaring rabbits.

Culture saved me. I’m trying to bring this out here. I already got little guys looking up to me, in their 20s or younger. I don’t tell them what to do, because I followed that way.–Glen Hondz

Man, I battled a lot of demons there. When I went in there, I was determined on just going there to get out quick, thinking that was a faster way to get out and then go back to doing what I was doing. Those people helped me open up my eyes, and showed me a better way of life, which was the Anishinaabe way.

Even though I put a smile on my face, they knew something was wrong. They grinded me every day. They kept asking me, “we can feel it, there’s something bothering (you).” I told them (about) my trauma, my sexual abuse, being surrounded by alcohol, my parents fighting, people coming in and out of the house. They got me to open up.

They have this program, a re-integrational program. That was a pretty amazing program. I think they should bring that out here more. We did a family tree of who all was drinking, and who all was sexually abused, and how it went down generation after generation. It’s really not a lot of their faults, because they went through it too, the abuse, gang life, poverty.

Culture saved me. I’m trying to bring this out here. I already got little guys looking up to me, in their 20s or younger. I don’t tell them what to do, because I followed that way. I can’t tell them “Oh, what you’re doing is wrong.” But I can tell them what I’m doing now is good. I’m following the culture, I’m going to meetings, I’m volunteering.

I just hope that it clicks in, because I know at a young age it didn’t click in for me. Not until I was older and saw how much damage I was doing to my family. That’s not the life I want to leave behind. I want to leave a positive legacy.

What are the most important things we as a community, city and province can do to reduce crime?

The addictions. More facilities, maybe a better understanding that it’s not their fault, it’s a disease. Meth caused me to do things I would never do now, or even before I started meth. I think Stony Mountain (Institution) should also put more programming in and try to help the men more, rather than they go in there and they get treated like an animal.

I’m sorry to say that, but it’s true. I went through it. I was locked down all the time. There were guards there that don’t care. In Milner Ridge (Correctional Centre), I had a case worker but he didn’t care at all. When I got out of Milner Ridge I got out to nothing. They promised me they’d help me get a place, but when I got out, I went right back to it.

What the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre taught me is that I do have support, there are tools I can use to keep on that path.–Glen Hondz

Even after I got out of Crane River, they put me on Redwood and Powers (in Winnipeg’s North End). I guess it was up to me to be strong and do what I have to do, but I ended up going right back to it within a month and a half. I had no supports. Or I did, but I didn’t use them. What the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre taught me is that I do have support, there are tools I can use to keep on that path.

When I went to Bruce Oake, it was a battle all over again. I was fighting my demons. I started getting back into the street life and hanging around with gang members. I had a relapse there and I almost went back (to jail). I could’ve went back, but it’s good thing that Bruce Oake saw hope in me, that I do want to get help.

Even right now, I’m starting from the bottom. I’m working my way up. I’m at a sober living house now. I’m volunteering with organizations like Mama Bear Clan, Agape Table and Manitou House, which is a halfway house. I just want to be there for the guys who come out feeling institutionalized and needing someone to talk to, someone to listen, give them some advice.

What do you wish people in Winnipeg knew about people with criminal records?

I wish they would understand that it’s not really everybody’s fault. It’s that re-integrational impact, it’s the environment they’re in. It doesn’t help if there’s a bar on every corner. I notice some are getting closed down… that’s what the community needs more. That and more programming for men, and not just for men, for the women as well.

They don’t have a facility like Bruce Oake for women. There’s women out there struggling too. I see a lot of women out there in poverty, with addictions. I see a lot of people get turned down and turned away from certain places. There’s more stuff for men then there is for women.

What I want for other people to see is that we’re trying. We’re trying to better our lives. We’re not bad people. I get judged a lot because of my lifestyle, because of the way I dress, the way I talk. People look down on that. Some people don’t agree that Bruce Oake should bring in people like (us), because I came from Stony.

Those guys say, “oh, it’s becoming a place for inmates.” But we’re trying to better our lives too.

Josephine Harper, 34

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Josephine Harper

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in a reserve that’s up north, mine’s Red Sucker Lake First Nation (situated about 470 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg). I was adopted by my mom’s auntie, she had me from when I was born. She’s the closest one I know to a mother. She’s a very nice lady, but from her upbringing she didn’t know how to be a mother herself, I guess, because she started when she was 16. That’s where my abuse came from.

We were poor. There was definitely a lot of struggles. I was sexually abused, because I can remember when I was four years old and how I was treated. Alcoholism came from my family. Me and my sister started drinking when we were teenagers. I was the one that would mostly always go drink to numb my pain from the problems I went through.

There was some stealing, breaking in, trashing places. I didn’t know nothing. I wasn’t taught. We would try to get high on anything, from air freshener to whatever chemicals. Or we’d drink, make home brew. To me, I realized I wasn’t feeling any pain or anything. It became a habit. We got so immune to it. I had no confidence at all, I had low self-esteem.

How did you first come into contact with the justice system?

When I turned 18 was when I moved here. I think I was only sober here for half a year or so. Then I met people and started drinking again, of course. I wasn’t doing any crimes yet, because I had to learn from seeing people do it. That’s how I learn stuff, is by simply watching. The way I do things, how I made it this far is… just by observing.

So from dealing with sexual abuse, abandonment, neglect, everything I experienced as a child, all my anger built up from my past. At that young age I didn’t know what anger was really, until I started drinking and blowing up on people. I’ve racked up assault charges because of it. I just didn’t know how to deal with it.

That led to stealing from stores to survive, because I was homeless. I didn’t know how to live. Of course I didn’t know how to communicate at that time. I was new in the city so I didn’t know where to go. I was with the wrong crowd, but we all have the same issues. The only difference between me and them is I am not scared to say it now, of why I am the way I am.

I was the one that would mostly always go drink to numb my pain from the problems I went through.–Josephine Harper

I just lay it right out in the open. I was sexually abused when I was a kid. I was neglected, I was abandoned. I don’t know the intimacy of a family member, where they’re supposed to hug, hold you, teach you. My mom wasn’t there.

The first time I got arrested here, I think I was 19. I can’t even remember for what. I’ve been arrested so many times… I think it was 2014. I was constantly in with assaults, one after the other. But I didn’t just go attack random people or jacking them, it wasn’t like that. It was more sexual abusers, because I witnessed people taking advantage of ladies passing out.

What most helped you make positive changes in your life?

It was a person. His name is Fedja, he works at Wahbung Abinoonjiiag (a North End healing centre focused on domestic violence prevention and crisis care). I was in jail, I think it was 2015. I was at that point where I couldn’t get out, not even to treatment. But my lawyer managed to get a chance if someone would bail me out, like an organization to watch over me… So my lawyer called all over the place and ended up with Wahbung.

It’s for domestic (violence recovery). Totally had nothing to do with my charges, but Fedja said “bring her in.” In the past, I never used to reach out, because I have this problem where I’d work with someone here, and they’d just stop working with me. It caused abandonment issues for me: “There you go, another person has abandoned me.”

It led me to think nobody wants to help me, I’m worthless. Then Fedja came along and I thought he was going to do the same thing, so I didn’t reach out to him at first. I kept on getting arrested… Each and every time he was there. He and his manager at the time would always call shelters and wouldn’t stop until they found one to have a roof over my head.

I didn’t even realize what they were trying to do, was be there for me. So how I changed my life, and started not going to jail is because of that. He showed me that not everybody is like that. He inspired me, and now I want to do that for other people.

When you look at the city now, what do you see as the main factors influencing crime rates?

The criminal things is racking up because these youngsters are going through what we went through. In order to lower that down, start working with younger ones, and make it possible for them to know there are people out there who can give you what your parents couldn’t give you, what anybody couldn’t give you when you were younger.

If somebody were to (have done) that for me, my life would probably be somewhat different.

Also, being homeless and institutionalized. I used to do crimes on purpose just so I could have a roof over my head. Believe it or not at least 35 per cent of people who are in jail do that, or maybe even 65. Just to stay sober, to gain your health and your mentality back, and to have a roof over your head for the winter. That’s why it spikes up in winter so much.

Those type of crimes, we did it out in the open and took our sweet-ass time just because we know we’re going to get locked up. At the time it was worth it. Not the stealing part, the going to jail part. Because who knew, maybe that would have been our last day alive (if we had stayed living unsheltered on the street).

These youngsters are going through what we went through… start working with younger ones, and make it possible for them to know there are people out there who can give you what your parents couldn’t give you, what anybody couldn’t give you when you were younger.–Josephine Harper

I would say 30 to 40 per cent of those people change their lives. It would be higher if they had support the way I was given.

What are the most important things we as a community, city and province can do to reduce crime?

People in jail, we all have the same situation, the same problems, but different ways it happened to us. That’s the main thing. Everything starts from childhood. Even if you didn’t experience the sexual part, there’s some kind of trauma. Being an adult, something traumatizing could happen, like your spouse gets killed, and you would know how to deal with it now.

What would help a lot with these people is to have someone like Fedja. Everybody in jail doesn’t have that kind of support, and they need as much support as they can have. Not the supports where (the worker is) just in it for the job. They have to mean it. We can tell who is sincere and who isn’t.

And reach out to them, as opposed to the other way around. What most people don’t know is we have a hard time reaching out. Especially being turned down. We don’t like being turned down, because then the negative self-talk builds up: “OK, I reached out and that person doesn’t want to help me, so I’m not going to try that other person.”

Instead of reaching out, a lot of people need to reach them. That’s what Fedja did for me. I didn’t reach out to him. He just stayed where he is and would always answer my phone call, or he would call me. “Do you need anything?” I’d say no just to make myself look good. But of course I did.

People in jail, we all have the same situation, the same problems, but different ways it happened to us. That’s the main thing. Everything starts from childhood.–Josephine Harper

In order to cut down on these criminal activities, (is about) simply working with them. It’s that easy, to be honest. Go reach out and just not walk away. Yes, they’re criminals, and definitely you’re going to be scared because they’re criminals, but deep down they’re nice. They’re nice people.

What do you wish people in Winnipeg knew about people with criminal records?

There’s a story behind it. There’s definitely trauma. It’s pretty much, “this happened to me, so that’s how I’m going to live.”

Even when I was homeless, I was helping other homeless people out. That’s the one thing about criminal people or homeless people — they have each other’s backs with clothing, food. We stole food, not to sell it, always to eat it. It was to share, because there was camp sites everywhere. We don’t only steal for ourselves.

That’s a very good thing about people that are homeless. They’re not selfish. Same thing with doing crimes. It all has to do with feeding yourself or whatever it is. Just too bad there’s not enough resources. There could be, but they decided for it to work like, “oh, they have to reach out to us.” That’s why kids are racking up on charges.

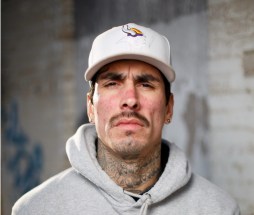

Jeremy Raven, 37

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Jeremy Raven

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in the North End with both my parents, mother and father. Life was good. I grew up playing sports, very active. My mom and father did the best they could with what they had, both loving supportive parents. Eventually, going through sports and school, I started meeting new people, new friends, and getting into other things growing up.

It eventually led to hanging around with a group of guys who weren’t always doing the greatest things, and I was involved in a lot of the things. It just led me to fall down a destructive path and unhealthy habits where I chose to do what everyone else was doing.

How did you first come into contact with the justice system?

Over time, it was like everyone was either going to jail, or getting out of jail. Because I was younger, everyone was always asking me, “oh, you haven’t been there yet?” So it was like, “this is what you gotta do.” I was trying everything I could to get into the system I knew nothing about. I was really excited to go, as messed up as it seems now.

I wanted to experience a life and a friendship with the people I was growing up with. It was just part of the way I was living.

(The first time), I was 11 years old. I remember going to the Youth Centre. I forget what it was that led me to come in contact with them, but I wasn’t old enough yet to actually stay in there, so they gave me a bus ticket and sent me on my way. I never mentioned it to my parents. I was just like, “I did it, I made it.”

Over time, it was like everyone was either going to jail, or getting out of jail. Because I was younger, everyone was always asking me, “oh, you haven’t been there yet?” So it was like, “this is what you gotta do.”–Jeremy Raven

From there, it was just getting involved in more and more things. Living a destructive lifestyle, not knowing the causes or effects it had on family or friends. Today it could be nieces, nephews, people that I love and hold close. I never knew those things until I actually started doing the work, and looking at my life and how I’ve affected others.

Addiction played a huge part of that, because I was out doing things so I could get money and buy my drugs. My whole life was in and out of the system, and making poor decisions, impulse decisions that created all this havoc or this mess that kept me a statistic in the system. Just another number.

What most helped you make positive changes in your life?

Reading. A lot of self-help books helped me identify some of the things I was going through or some of the issues I struggled with. And making myself aware of what I was going through, some of the emotions or things I was dealing with or struggled with that I didn’t know, or I wasn’t taught growing up.

It was good because it set a routine. I had to keep motivated and disciplined, and work to better myself, regardless of all the emotions I was suffering from. And healing, so I could project these good feelings that I’m feeling about myself now. So I could be the person that I truly desire to be.

Dec. 19 marked three years I’ve been out of jail. That was the last time. I was in a program while incarcerated then that helped deal with trauma and addiction, mental health. Just working those angles of how I could better my life, looking at the deeper-rooted issues, counselling.

When you look at the city now, what do you see as the main factors influencing crime rates?

A lot of it is the environment they grow up in. Everything I did revolved around my community, and how the people I was with were doing things. It was never good, but at that point in my life… I really didn’t see anything wrong with it because I was providing for myself and helping others with the things that I was doing.

I didn’t realize how much that affected the community, and how much hurt I was inflicting on people.

Going up and down Main Street or around the neighbourhoods, a lot of it is people who are suffering from mental illnesses, not having resources or medication to tap into so they can find a positive outlet to gain control of what they’re going through. The help that’s really going to take them on a long road.

Everything I did revolved around my community, and how the people I was with were doing things. It was never good, but at that point in my life… I really didn’t see anything wrong with it because I was providing for myself and helping others with the things that I was doing.–Jeremy Raven

Drug activity isn’t helping the situation, because some of them don’t even know that they have these problems, and they do drugs and it affects them differently or it creates psychosis. It gets them more involved into criminal activity. It’s just a cycle that will keep going unless people get the help and want to do the work and take the action.

What are the most important things we as a community, city and province can do to reduce crime?

I think for people that have already been charged and gone through the system, programming that helps them deal with the trauma, and rehabilitation so they can heal from within will help identify a lot of things for them to pinpoint the issues they’re struggling with. That will go a long way, rather than just the recidivism, that revolving door.

For the younger generation of kids, I think sports programs and literacy programs are things that are going to help them grow and think for themselves, rather than repeat the behaviours they see at home. It’d be a lot easier for someone to think for themselves about what they’re seeing every day, rather than gravitating towards that lifestyle.

What do you wish people in Winnipeg knew about people with criminal records?

Be kind to them. Give them a chance. Sometimes it’s not that people want handouts, sometimes they just need a hand up to be able to go that distance, feel that confidence, and people being genuine with them and showing them a different way than what they were shown.

Terrence Morin, 35

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Terrence Morin

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Thompson, Manitoba, in a broken home, broken family. My mom and my dad were alcoholics, abusive. I had a few older brothers, older cousins, and they were in gangs. They did bad stuff. Me growing up seeing that, it was like I had to out-do them, or be better than them.

Addiction and violence was the normal for me. I grew up poor, so if you didn’t get it, my brothers encouraged me to go get it: steal, rob. But I had one good brother who said, “only do it if you really have to.” And I had another brother did it because he was trying to be “gangsta,” trying to prove to other guys that he was more dominant, smarter.

I had one big brother who moved away because he wasn’t about that life. He was a different breed. He wasn’t like the other brothers, stealing and fighting. He was a nerd. He liked school. None of us could understand it. Maybe we didn’t choose to.

I just wanted to be accepted by them. I was a little brother once upon a time, just following them around, crying “no, I want to come hang out with you.”–Terrence Morin

We moved to the city, and then I got introduced to a whole new level. More crime, more opportunities to do crimes. I got introduced to gangs. I was drawn to it. I wanted to be like my brothers. I wanted to be bigger and badder, do more crimes, sell more drugs, fight.

I just wanted to be accepted by them. I was a little brother once upon a time, just following them around, crying “no, I want to come hang out with you.” They’d be like “no bro, you don’t.” I understand now they were trying to be big brothers, telling me no, but at that time I couldn’t understand what they were trying to tell me.

What most helped you make positive changes in your life?

I think since I’ve been 18, the total I’ve been free is four years, five years. I think the most I’ve been out at one stretch would be a year, then I’d go back to jail for like two years, 18 months, three years. It accumulates. The majority of my life I’ve been institutionalized. It’s all I know.

I know Jeremy (Raven) from jail. He had an opportunity to go to the privileged part of jail, it was minimum security. He had an opportunity to rehabilitate himself. So I tried to go where he was, but I was considered a high-ranking gang member, so I couldn’t go. “Your record is too violent.” So I’d get mad, I’d rebel against the system.

I’d go “oh, you expect us to rehabilitate ourselves, but you won’t give us a chance. So I’m going to go off.”

I felt just there was no hope, until I finally realized I was being in that cycle over and over again. I had an epiphany in jail. I was just looking at my wall, and I was thinking: this is what crime does. None of it’s appreciated anyways by anybody, they always want more. I gotta prove to myself that I can stop this. I gotta prove it to my family. I got kids.

You know the 12 steps? I had a Step 1 problem: not admitting I have a problem. I always said, “I don’t have no problem, I’m good.” I sat there one night and thought, “f–k, I do have a problem. Drugs is part of my criminal activity. I do crime to get drugs. I sell drugs to do drugs.” It all comes together, right? Then I was like, I gotta stop that cycle.

I had an epiphany in jail. I was just looking at my wall, and I was thinking: this is what crime does.–Terrence Morin

So I was sitting in jail watching the news, and Bruce Oake Recovery Centre was on the news. It just got to me: “I want to go there. I need help. When I get parole, maybe I’ll try this out.” I’d tried (other programs), they didn’t really help me. I didn’t hear something I needed to hear (in those programs), but I heard something I needed to hear at Bruce Oake.

It had something to do with the 12 steps. That if you walk and talk in a good way, good things will come back to you. It’s not going to come back to you right away, you got to work for it every day. I’ve been working since I got out, and a lot of good things are coming my way. Tim (Barron) taught me that too. I’ve got a good mentor.

What are the most important things we as a community, city and province can do to reduce crime?

More guys like us, straight up. Some guys are scared to speak up like this. I was kind of nervous, but I was like, “f–k it, I’m going to be that light for other guys.” Some of us are afraid because yeah, we have a gang past. I have a long gang past. But this is me doing my good thing, even though sometimes I’m scared it’s a liability for myself.

We need more guys like us, like a team. If there was a resource centre of guys all working that have a past like us so we can show them how to take those steps to change. So we can say, “I’ve done it. Tim’s done it. Jeremy’s done it, and he’s doing a great job.” At the end of the day, you got to want it. I wanted it, but someone showed me too.

They drive by us every day but they don’t know how it is, really. They just see us on the street, or they hear us on the news. They don’t understand what we had to go through growing up.–Terrence Morin

Sometimes I talk differently at the (Bruce Oake) Centre, but it’s all good because they understand what you’re trying to tell them. Sometimes when you talk to people, I don’t know any of the big words that they’re saying. I’m learning still. Slang is just as good as those big words. It means something to us, because we understand it.

So, a men’s resource centre… where they’ve got computers to help guys look for jobs, and a place where a guy would feel comfortable to come ask for help… a support system for guys who are just getting out of jail that would feel comfortable, where guys can come and chill. No gang activity, all that stays outside, this is a positive place.

What do you wish people in Winnipeg knew about people with criminal records?

I wish I could go out with a couple of guys from Woodhaven or one of those big neighbourhoods way out there by Waverley, and say “these are my shoes, go walk in them for one whole day and see how it is.” It’s not your fault the way we are, but I just want you to understand the way some of us had to grow up.

They drive by us every day but they don’t know how it is, really. They just see us on the street, or they hear us on the news. They don’t understand what we had to go through growing up. But you can work your ass off to get out of there. I’m still in that process, I’m not there yet, but I’m going to be there. I feel good about where I’m at right now.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.