Fateful mission Former Mountie believes guarding Soviet satellite caused rare cancer

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/05/2022 (1299 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

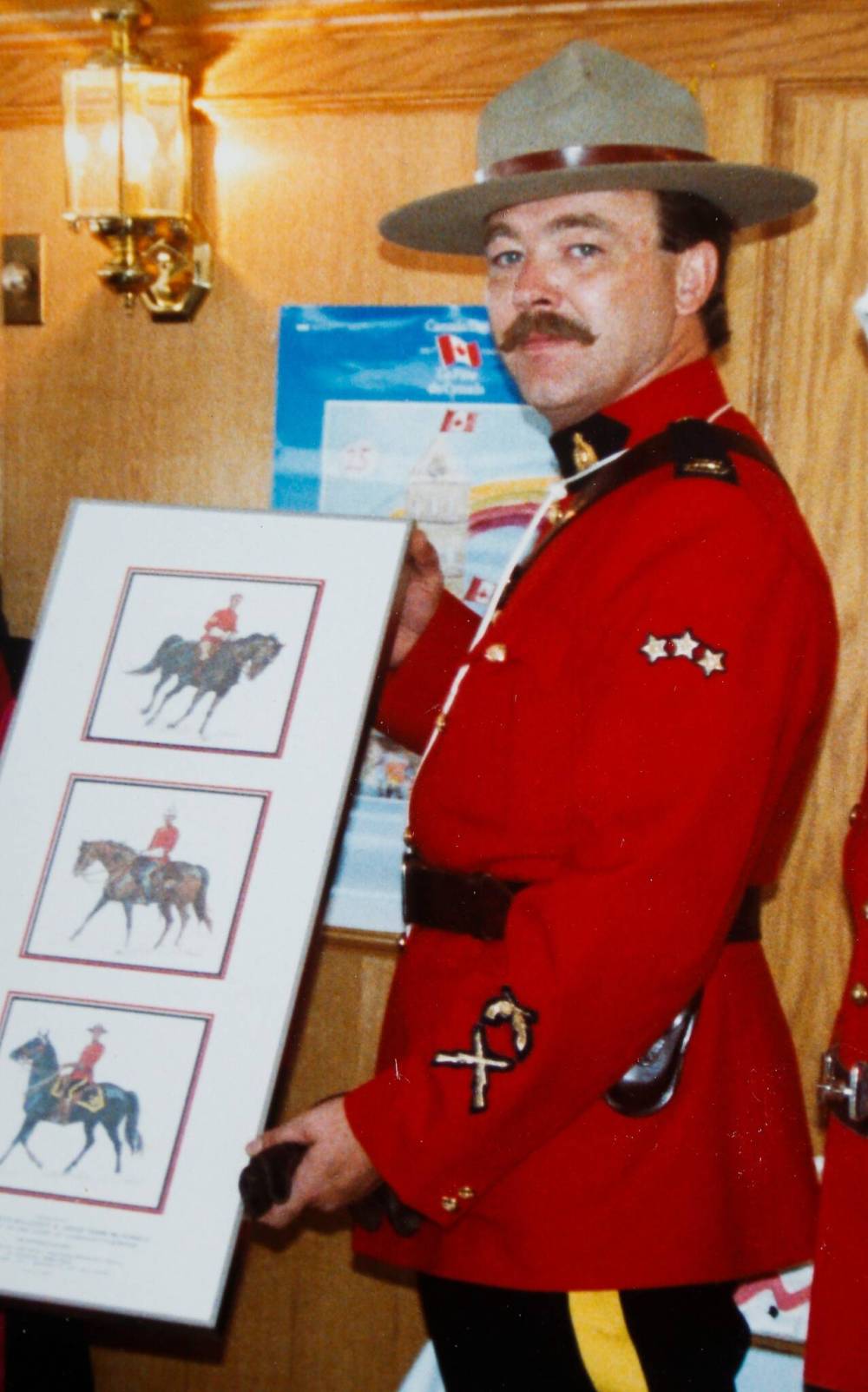

When a Soviet satellite plummeted to Earth and landed in the Canadian Arctic in 1978, Mountie Lance Rayner was put on the case.

The 24-year-old, along with fellow officer, 22-year-old Bob Grinstead, were two of the first on the scene when reconnaissance satellite Kosmos 954 landed in Lutselk’e, a settlement on the eastern shore of Great Slave Lake.

The Mounties were assigned the task of preventing the Soviets from repatriating the satellite.

It was a short mission; Rayner said he was in and out within three days. He said he was given no safety equipment. Instead, he was handed two dosimeters, which measure radiation exposure. He was told to wear one on his skin and another on top of his winter gear.

“We never gave it a thought. It’s 1978 (and) I’m 24 years old then,” he said.

“I had no clue what I was exposing myself to, or what the RCMP had exposed me to.”

“I had no clue what I was exposing myself to, or what the RCMP had exposed me to.” – Mountie Lance Rayner

Earlier this year, Rayner, who lives in Ste. Agathe, was diagnosed with a rare malignant parotid tumour. Although the tumour in his neck was removed, he has been diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer.

High levels of radiation have been linked to salivary gland tumours and cancer and, while being screened, Rayner was asked if he’d been exposed to radiation. He mentioned his mission to the Arctic in January 1978.

“I got odd looks, to say the least, because you have to be likely 60-odd-years old to even know about it, because it’s lost history right now, I think,” Rayner, 68, told the Free Press.

That experience has haunted Rayner as he fights cancer. He remembers the RCMP and military members sent to the site were “ill-prepared.” The crew was given food rations that required water, so they melted the snow on site. They were told not to get too close to the satellite debris, he said, but they slept less than 30 metres away from it.

He wonders if that mission — part of the five years he spent as an officer in the Northwest Territories — is responsible for his cancer.

He’s applied to Veterans Affairs Canada for coverage for his cancer treatment. More importantly, he wants recognition from the RCMP that his service likely directly contributed to his terminal illness.

“It’s no different than somebody shooting at you with a gun in January of 1978, but the bullet doesn’t really hit me until I get my diagnosis in March of 2022,” he said.

He hasn’t heard from the RCMP, and said he was never given information about Kosmos or radiation poisoning.

The RCMP said it wouldn’t be able to comment on the issue. The Free Press had asked whether it had similar testimonials from other ex-officers exposed to radioactive material.

The Northwest Territories was thrust into the Cold War spotlight when the uranium-powered satellite Kosmos 954 crashed on Jan. 24, 1978, after the Soviet Union had launched it four months earlier. The crash, which was far from communities, was reported by travellers four days later.

Within 24 hours, both the Canadian and the U.S. military had arrived, and began Operation Morning Light, an analysis and cleanup. It was learned that the radioactive core of the satellite hadn’t been destroyed in the fall to Earth.

There was radioactive debris around it, which posed a danger to both researchers and officers on site, as well as civilians in the area.

Rayner said he was never told his dosimeter readings.

His cancer diagnosis kept him up at night for a while, he said, but he’s come to terms with it now.

“I’m taking it in stride. I tell a lot of people that being an RCMP member, for some reason I had it in my head that I would never make it to this age anyway, which is a tough thing to accept… But once I was married, and had children, all that changed,” he said.

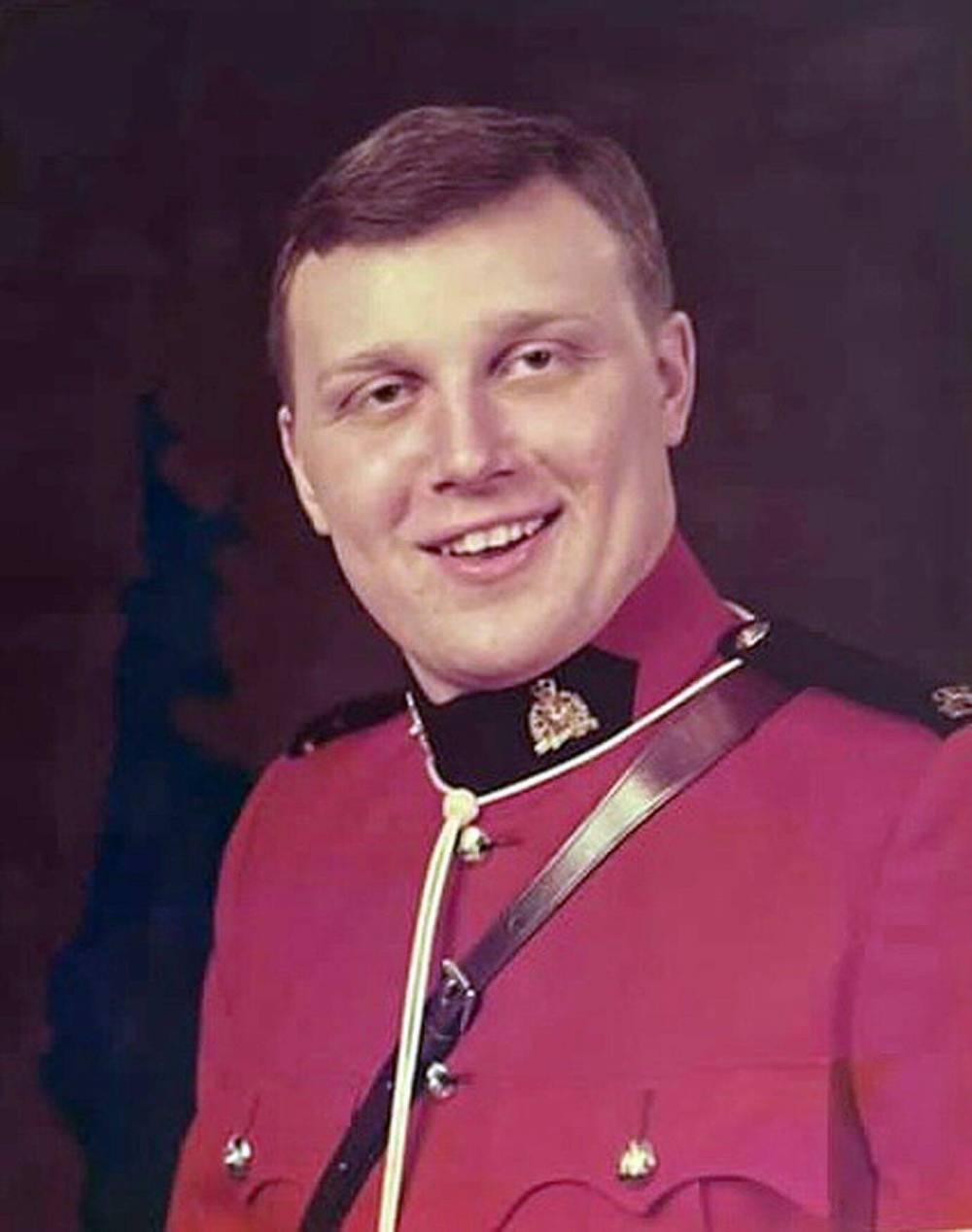

Rayner believes Grinstead, his former partner, was a victim of the Arctic mission, too.

In 2012, Grinstead called him to say he had leukemia. He had been a Mountie for 24 years. They kept touch until Grinstead died in 2019, and Rayner said he’s speaking out for him, too.

“I appreciate people feeling sorry for me, but that’s not the intent of the message I want to get out. I want to be recognized for my co-workers that basically died as a result of the RCMP’s — I have a hard time calling it negligence,” Rayner said.

Jennifer Grinstead Mason remembers her dad as loving and a hard-working Mountie.

“My dad was a very committed RCMP member, my dad was a very funny man. He loved his family, he loved his community, he loved to help people,” Mason said.

She said her father was told his leukemia had been caused by a chromosome mutation often seen after a person has been exposed to high levels of radiation. He recovered twice, once after chemotherapy and again after a stem cell transplant, but died after his third bout of leukemia, when another attempt at a stem cell transplant didn’t take, on Aug. 23, 2019. He was 63.

Their family has so many unanswered questions, including whether her brother Boyd was affected because he was conceived after the Arctic mission.

“Does this radiation pass down genetically? This radiation exposure to my brother, does it pass down to his children? We don’t know,” she said.

“Does this radiation pass down genetically? This radiation exposure to my brother, does it pass down to his children? We don’t know.” – Jennifer Grinstead Mason

Grinstead had written a long report that provided background on Kosmos 954 and Operation Morning Light, along with documenting his own illness and its connection to radiation poisoning. He received “a small amount” of compensation from Veterans Affairs, Mason said, but was never recognized for what he had sacrificed by guarding the satellite debris.

“He was disappointed, but he felt like that was all he was going to get at that point,” she said.

Mason believes the satellite incident, and potential exposure to radiation, could have ramifications for years.

“There could be many, many, many health issues that are still taking place from generation to generation in those communities up north that absolutely are not being recognized,” she said.

malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.