Bonded under the basket Gordon Bell Panthers 1981 varsity boys basketball squad remember brotherhood and glory on the hardwood

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/03/2022 (1354 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

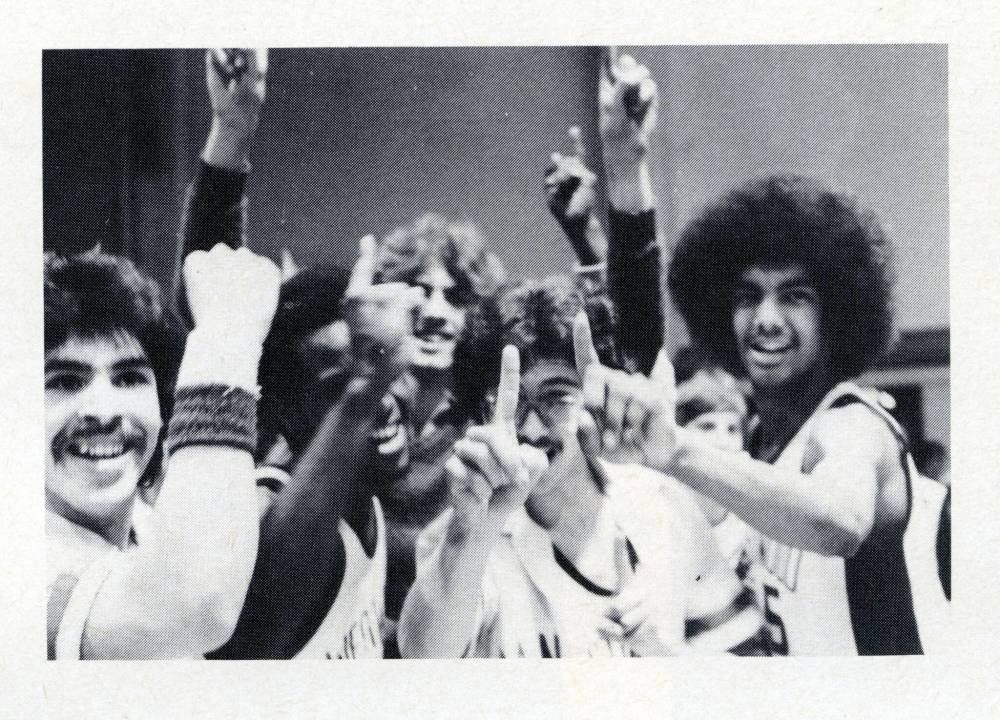

On a cool spring night 41 years ago, the Gordon Bell Panthers were making history.

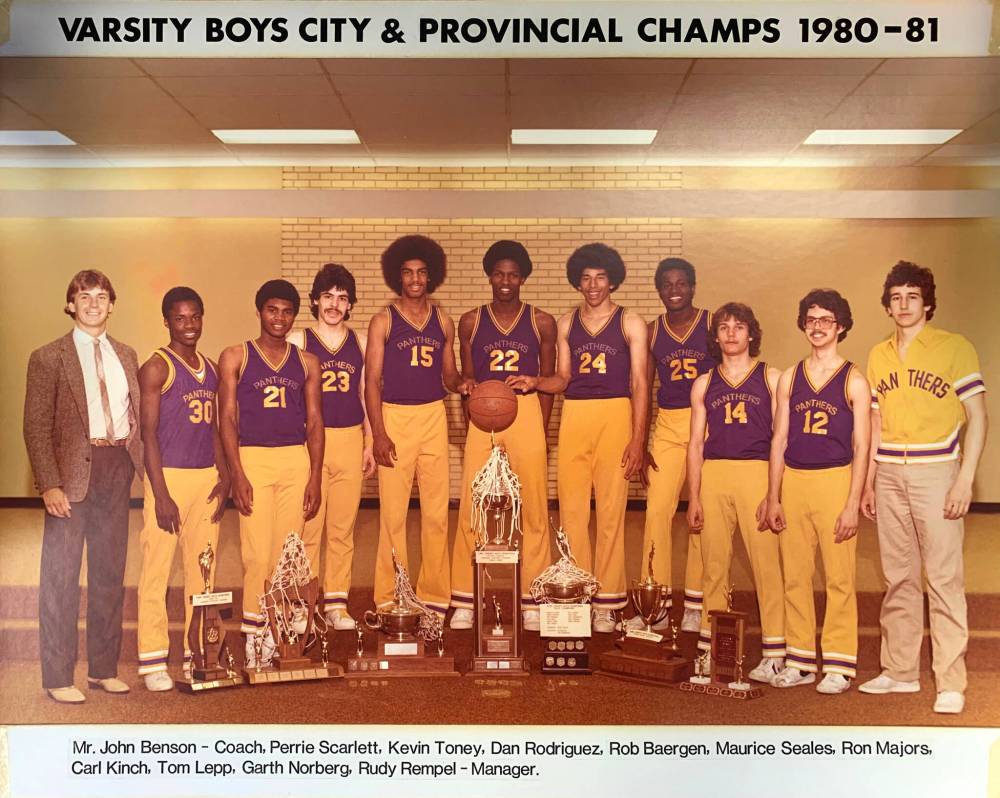

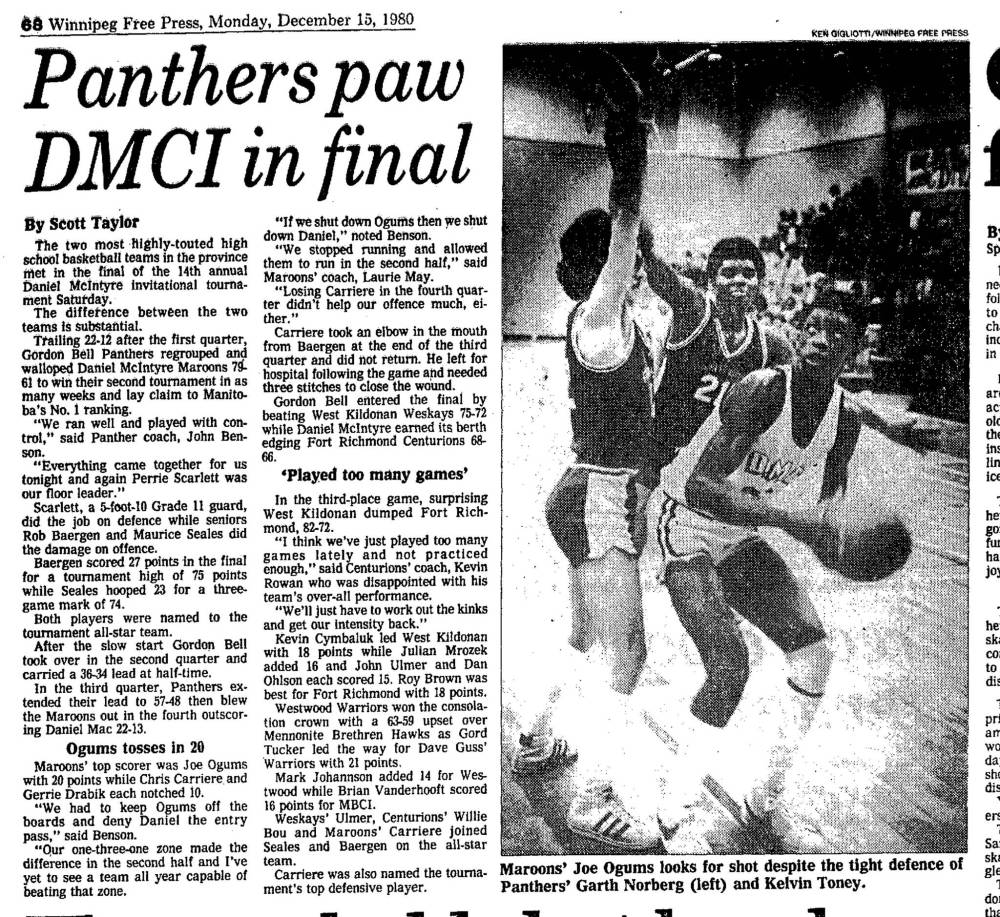

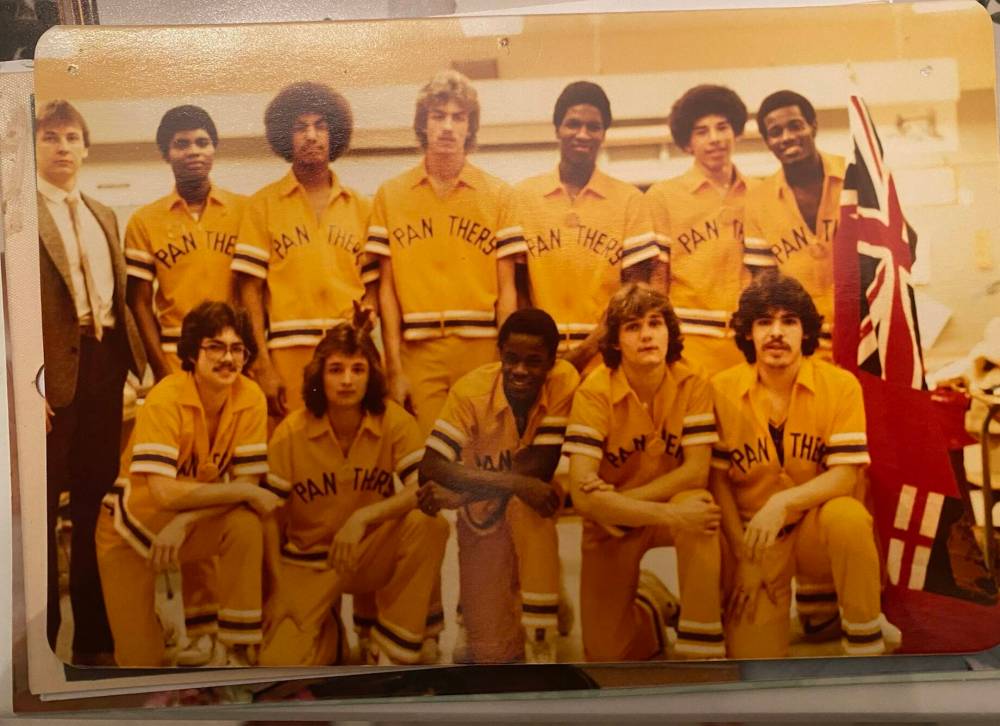

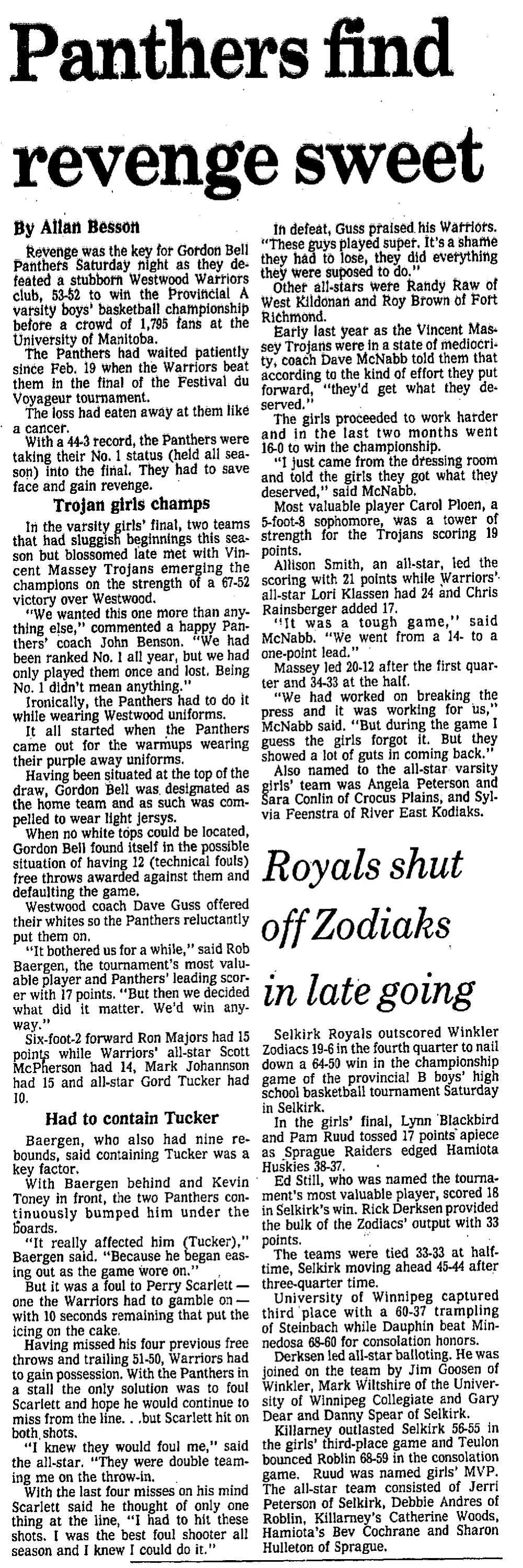

A few newspaper clippings have survived, although the photographic evidence of their accomplishments is scarce. Further proof can be found on YouTube, where a flickering video of a basketball game played in a dimly lit Bison East Gym on March 21, 1981 has been uploaded.

Final: Gordon Bell 53, Westwood 52.

Most people don’t remember the score but they do remember the team.

A crowd of 1,795 witnessed the game and years later, whether Kevin Toney is speaking at a business seminar, grocery shopping or playing hoops with his 14-year-old son Kai, he is reminded of the Black Panthers with astonishing frequency.

“I remember that team,” perfect strangers tell Toney, who was Gordon Bell’s scrappy sixth man when they won the first provincial varsity boys basketball title in school history all those decades ago.

He is 58 years old but he can’t escape — nor does he wish to — reminders of the accomplishments of a band of brothers that also included guards Perrie Scarlett and Maurice Seales and forwards Ron Majors, Rob Baergen and Carl Kinch.

The Panthers were the first all-Black starting lineup in Manitoba history and are probably more famous for how they won. They were stylish, attacking the basket with a ferocity never witnessed before on the provincial scene and they were the best show in town.

“How could you not want to be around these guys?” says Rudy Rempel, who opted to serve as the student manager of the ’81 team. “They were just so awesome. Just to watch them and watch their interplay was quite something and it must have been intimidating for the people they played because it was as if they had come from another country or another planet.”

Despite their mythic reputation, the Panthers were firmly grounded — at least when it came to real life.

Majors, who was raised by his single mom in the West End — and “moved 40 times between (age) three and 20,” he says — admits his upbringing was challenging but speaks with pride about what they were and what they became.

“Being from an inner-core school here at Gordon Bell, I can honestly say the five, six core people like Mo, Kevin, Rob and me, Perrie and Carl, you couldn’t find better well-behaved and aware and just respectful young men,” says Majors, who lives in Winnipeg and works as a manager in the provincial civil service. “We never got in trouble for anything — not the greatest students at times, but basketball took us away from everything else that possibly could have put us in it in those spaces…

“If anything, that was more important than even playing basketball and winning a championship… it set us up to move on without all that other noise going on. There was a lot of negative influence or things we could have done. Basically, our gang was our team.”

● ● ●

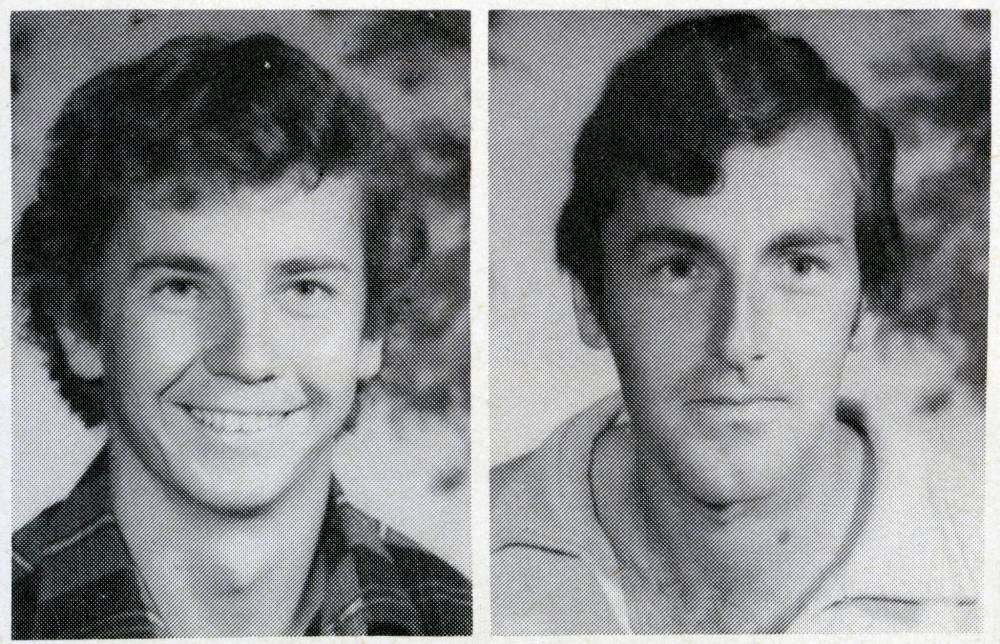

Six years before the championship season, Rick Suffield came west looking for adventure.

He was 25, ambitious and anxious for a change of scenery. After four years of teaching and coaching at Richelieu Valley High School in McMasterville, Que., he wanted to leave a province vibrating with political and cultural tension that erupted during the 1970 October Crisis.

In fact, deputy premier Pierre Laporte was found murdered by separatist FLQ terrorists only three blocks from where Suffield lived in St. Hubert.

With political and ethnic tensions still simmering, Suffield had arranged to visit Gordon Bell High School in the spring of 1975.

The school, at the intersection of Maryland and Broadway, was in the heart of Winnipeg’s gritty inner city and had a modest athletic tradition. The football team was competitive but there wasn’t much else to get excited about. Principal Herb Lother wanted to change that.

After a 30-minute walking tour of the school building and grounds — “there are some really great athletes in Grade 7 and 8,” remarked Gordon Bell phys-ed teacher Donna Crowe as they passed through the middle school gym — Suffield sat down with Lother.

“He said, ‘I want you to come here and I want to know one thing right now: Can you turn this school into a basketball school over a period of time?’” recalls Suffield. “Well, what am I going to say? I’m young, I want a job. I said, ‘Absolutely.’

“I was probably lying through my teeth. And I didn’t know those kids at the time. I said, ‘absolutely’ because I was pretty confident at the time. He said, ‘OK, you’re hired.’”

A few months later, Suffield was learning quickly the school’s reservoir of athletic talent was brimming with potential.

Three young Black players — Darryl (The Flea) Stevenson, Tony Scott and Keith Lynch — were already in the system and would eventually form three-fifths of the starting lineup of the school’s city championship squad in 1977.

Only four years behind this trailblazing group was a prodigiously talented bunch made up of guards Scarlett and Seales and forwards Rob Baergen and Carl Kinch. Majors would join the big four in Grade 10, and the roster would be further supplemented by Kevin Toney, who was a year behind.

Gordon Bell’s super six, which constituted the first all-Black starting lineup in provincial high school hoops history, have an almost mystical presence in the public imagination.

Four decades ago, they represented an athletic ideal. These were six players so celebrated they packed gyms across Winnipeg when high school sports routinely drew few spectators. The predominantly Black Panthers — six of the team’s 10 players had roots in the Caribbean — were viewed with awe, sometimes even as a threat.

More than anything, they changed the way the game was played. Before 1981, the high school game was archaic — a slow-moving, half-court spectacle played mostly below the basket.

Gordon Bell’s soaring, rim-rocking style was all more remarkable because the innovations of the three-point line, 30-second shot clock and breakaway baskets were still some years away from being implemented on the local scene.

“They played great basketball,” says Joe Di Curzio, who went on to coach provincial title squads at Tec Voc in 1985 and ’86.

“If they would’ve had more people — they played zone most of the time — they could have played some incredible man-to-man defence because they were all so athletic, but because they didn’t have much of a bench they couldn’t do that. But their work ethic was unbelievable.”

“Things like the behind-the-back dribble, making three or four moves to beat somebody to the basket wasn’t that popular back then and they used it, right?” – Joe Di Curzio

Di Curzio says the Panthers not only changed the way the game was played, but how the players were expected to look.

His championship teams at Tec Voc liked to refer to themselves as the Team United Nations, with Filipino, Black, East Indian and Indigenous players becoming fixtures on the court.

“Things like the behind-the-back dribble, making three or four moves to beat somebody to the basket wasn’t that popular back then and they used it, right?” says Di Curzio of the ’81 Panthers.

“And they also were very good at attacking the basket. They weren’t intimidated by say, a six-(foot)-five guy. They were not afraid to challenge and they knew how to finish going against somebody that tall.”

Gordon Bell’s attacking approach appealed to many younger players, including brothers Clive and Delroy Griffiths at Tec Voc. Clive idolized Scarlett and fell under the spell of the Panthers’ early version of Show Time, often begging Di Curzio to schedule practice earlier in the day so he and his brother could watch them play.

“The way these guys passed the ball, shot the ball and the team chemistry that they had, I got attached to basketball,” says Clive Griffiths. “Those guys were rock stars in Winnipeg.”

Another coach, Oak Park’s legendary Randy Kusano, is unequivocal about the ’81 Panthers’ place in history and how they compare to the great teams that came after them.

“If that Gordon Bell team played now they would shine because all the rules favour a team like that,” Kusano says. “They could get up and down the floor and you’ve gotta shoot (the ball with a shot clock), so it would really favour them. Their transition was amazing as it was. They would be dominant now.”

● ● ●

Before they became stars, Gordon Bell’s super six were influenced by strong male role models at the school.

In those early days, Suffield and Mike Gaston, a Black history teacher, helped to fill the bill.

Gatson, who died at age 65 in 2005, was a commanding presence in the school hallways from the early 1960s onward.

His background as a former pro athlete — he pitched for a time for the Winnipeg Goldeyes in the original Northern League during the late 1950s — carried extra weight. A transplanted American, the Alabama-born Gaston had first-hand experience of hard times while growing up in the racially divided Jim Crow South.

“Where he came from it was tough,” Toney says. “He was always on our cases in school. He took a lot of Black kids under his wing and he said, ‘Listen, this is the way the world is, you’ve got to work your butt off. You’ve got to be the best you can be.’”

Gaston’s wisdom wasn’t reserved for the school’s Black students.

“Mr. Gaston was an intimidating dude. He had a presence about him and a gravitas to him. He was like the Morgan Freeman of our high school. You listened (to him).” – Rudy Rempel, student manager of the ’81 team

“Mr. Gaston was an intimidating dude,” says Rempel. “He had a presence about him and a gravitas to him. He was like the Morgan Freeman of our high school. You listened (to him).”

Gaston also served an important support role in the gym, opening the doors early in the morning for the basketball-crazed bunch until Suffield arrived at the office.

Gaston supervised lunch hours in the gym where throngs of students and hangers-on from other schools dropped by to eat and watch the Panthers elite play pickup games. In summer, he operated the daily open gym drop-in centre from 1 to 10 p.m.

● ● ●

As a kid, Perrie Scarlett had an intensely personal feeling about school: he hated it.

Given up by his birth parents shortly after they emigrated to Winnipeg from Jamaica when he was nine, Scarlett was shipped off to the Children’s Aid Society and then into foster care. He remained with his foster mom when she moved from Garfield Street to a new group home in Unicity.

The change of scenery didn’t mean he gave up on his friends in the old neighbourhood. It was just a long bus ride away from hours of fun on the basketball court, football or baseball fields.

A close friend, Rob Baergen, lived on Arlington Street. So did another buddy, Maurice Seales.

The three kids had grown up playing on the outdoor courts at Laura Secord School and their interests ran the gamut — football, baseball, soccer and hockey.

“Rob and I were peas in a pod because I was in the foster home and he was also adopted,” remembers Scarlett.

Following Grade 12, Scarlett returned to Gordon Bell to improve his marks in hopes of qualifying for the University of Winnipeg with the intention of playing for the Wesmen. He got his wish, but just barely.

Teachers like Henry Huber, a member of Gordon Bell’s history department, saw something Scarlett didn’t even recognize in himself at the time.

“I said, ‘I need marks to go to university,” recalls Scarlett, now 58. “He said to me, ‘Scarlett, I’m giving you this mark but I hope I never see you again.’ It was awesome!”

He went on to earn an education degree at the U of W before continuing his academic and basketball careers at the University of British Columbia and spending seven years playing pro ball in Japan.

Today, he is a learning support teacher at Fraser Heights Secondary School in Surrey, B.C.

He also coaches basketball and other sports and moonlights as a teaching golf pro. Talking about the irony of the career path he has taken makes Scarlett laugh.

When he gets serious, however, he credits his childhood fascination with sports for keeping a sense of balance in his life. Often, there was a community looking out for him when he least expected it.

“Sports was our deal. We had friends who ran with the crowd, right? I tell this story (to my students). Back then there was lots of drugs and stuff and we’d go to parties and, you know, and a guy would go, ‘Scarlett, what are you doing here? Get out!’” – Perrie Scarlett

“Sports was our deal,” he says. “We had friends who ran with the crowd, right? I tell this story (to my students). Back then there was lots of drugs and stuff and we’d go to parties and, you know, and a guy would go, ‘Scarlett, what are you doing here? Get out!’”

The real chemistry came out on the court.

Seales, who later changed his surname to Sampson for legal reasons (adopting his mother’s maiden name in order to match his passport for the purposes of registering for university), was especially close to Scarlett and Baergen. The three had a symbiotic relationship from an early age.

“I think the three of us were all pretty much in the same situation,” says Sampson, born in Guyana before coming to Canada as a seven year old in 1972. “I mean, Rob came from an adoptive family.

“My parents had been on and off — separated, not separated — so I think we were just always together with each other. No matter what happened, we always had each other’s back. That’s what drove us.”

● ● ●

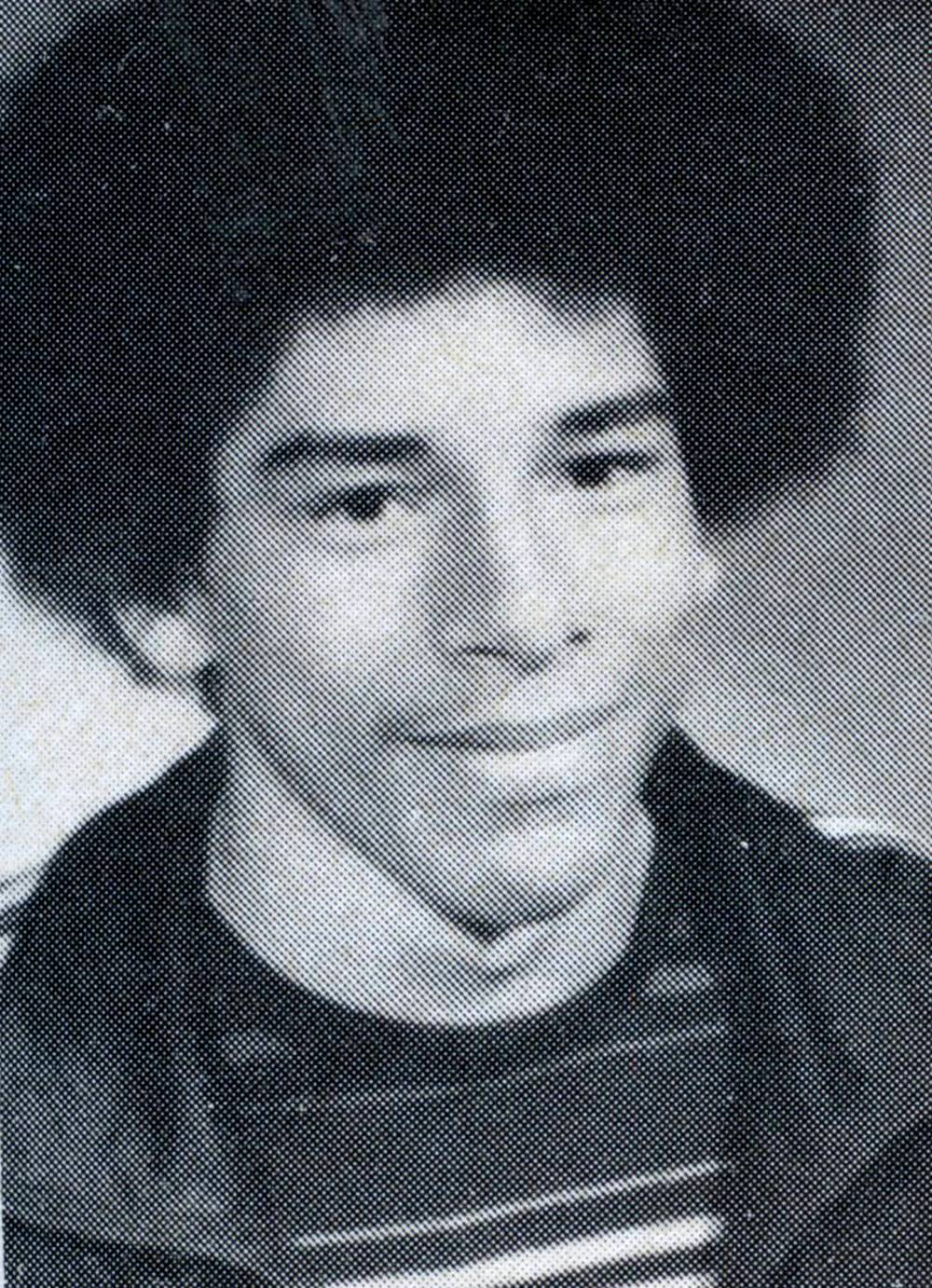

On a team filled with stud athletes, Rob Baergen was the one who most often heard fans chanting his name.

His visibility was accentuated by a massive Afro that announced his presence.

“He loved his Afro,” says his widow, Portia Sam, who first met Baergen at Gordon Bell. “He liked the way when he ran up and down the court it would bob up and down. People mentioned it and everybody noticed it.”

At six-foot-four, Baergen was the tallest of the group and throughout his childhood he displayed a preternatural gift for the games he played — football, baseball and hockey.

When basketball eventually became his sport of choice in high school, he had the soft hands of a shortstop and the physical presence of a hockey enforcer.

If you messed with one of his teammates, you would also have to answer to Baergen. That toughness never surprised Betty and Bob Baergen, the white parents who fostered Rob as a four-month-old and finalized his adoption when he turned four years old.

Betty remembers a “kind, gentle kid” who learned to endure the taunts of “zebra” and “Oreo” in elementary school.

While his birth mother was white and his birth father was a Black man from Jamaica, Rob grew up attending Sunday school at Bethel Mennonite Church.

When he was nine, while playing with his friends near his Arlington Street home, Rob was struck by a car when ran onto the street.

Suffering a broken collarbone, punctured lung and broken leg in the mishap, he spent a week in hospital before he was able to return home. Within three weeks, he had discarded the sling he had been wearing and was taking swimming lessons.

Sam remembers her husband’s fierce drive to succeed.

“He was a great sportsman, but I mean it was about winning,” she says. “It was 100 per cent about winning.”

Baergen was fiercely proud of his Jamaican roots and would sometimes communicate with his Gordon Bell teammates in patois, the English-based creole language.

“That was fascinating to me,” Rempel says. “But I remember Rob quite unequivocally said, ‘No, it’s not for you.’ Like, ‘You can’t talk. That’s for us.’ ” And I was like, ‘OK,’ and I felt terrible. So it was just trying to figure out the meanings of ‘raasclat’ (a derogatory term) and all this stuff that they would say to each other…. It was their code. I’ve subsequently discovered that a lot of this was straight from the Caribbean.”

After high school, Baergen played one season for Suffield, who had departed for Lakehead University prior to Gordon Bell’s championship season, but never found a fit with university life, leaving school before gravitating to the building trade.

Then in 1991, after years of cajoling from Scarlett, Baergen and his wife moved to Vancouver, where he worked as a plumber and independent contractor. When most parents are focused on watching their own kids play — Baergen and Sam had a son, London, and a daughter, Tanner — he was still an active baseball, basketball and football player well into his 40s.

“He never lost the edge that he had — that competitive edge,” says Sam. “He would play a football game and it was like it was a Super Bowl. You’re like, ‘Really, dude?’ I used to get really upset (with him). I was like, ‘What are you doing? You have to go to work tomorrow.’ ”

Through most of his adult life, Baergen dealt with recurring stomach issues and he used antacids to calm his digestive system. In July 2011, he phoned his wife complaining of an excruciating pain in his back and hurried to hospital.

Not long after, he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and he died on Aug. 28, 2011. He was 49.

“He went there and never left…. It was 34 days,” says Sam.

● ● ●

Kevin Toney lived the immigrant experience.

In 1970, his mom, Helena Liverpool, left her home on the Caribbean island nation of St. Vincent and moved to Canada to seek a better life. Young Kevin stayed behind with his grandmother while Helena laboured at two or three jobs simultaneously, working six or seven days a week.

“My mother was a very hard worker,” Toney says. “The fact that she had to have the courage to leave a place and where you know no one, pretty much, and leave your kid behind because you couldn’t afford to take him. And then (five) years later, she sent me a plane ticket.”

Toney and his single mom settled into an apartment on Alloway Avenue and it took time to adjust to his new life. At home in St. Vincent, he had neighbours who lived in houses with dirt floors and he rarely wore shoes, except to go to church on Sundays.

The blistering cold of Winnipeg winters was something else.

He had what he believed was a fairly routine childhood, but racism, something he hadn’t encountered in his birth country, was a constant presence.

Two episodes are permanently imprinted in his memory. He recalls being bewildered after being called the N-word on the playground at Mulvey School in Grade 6, the first time the slur had been directed at him.

“Those are things you just never forget. So there wasn’t any overt racism in terms of people coming after me, but those things kind of stick with you.” – Kevin Toney

A second, perhaps even more traumatic episode, came two years later while he was standing with his mom at the corner of Westminster Avenue and Maryland Street, waiting for the No. 17 Stafford bus. Two white kids leaned their heads out of a bus window and bellowed the N-word while spitting on the mom and son below.

“Those are things you just never forget,” says Toney. “So there wasn’t any overt racism in terms of people coming after me, but those things kind of stick with you.”

Those intolerant attitudes have informed Toney’s life ever since. Highly motivated by the desire to improve himself, he pushed himself in the classroom and in the gym.

After high school, he played three seasons of university volleyball for the Wesmen — the starting five Panthers all played university hoops to some degree — before transitioning to the working world, although he remained closely tied to the neighbourhood by spending more than two decades as a volunteer coach at Gordon Bell.

Today, the 58-year-old Winnipegger is a self-employed marketing manager.

“Our feeling at this time was we’re from Gordon Bell, we’re representing our school, our team is predominately Black and that was a motivation, for me anyways, because based on the history, we weren’t supposed to do very much,” he says.

“We’re lazy, you know? All the stereotypes, right?”

Kinch, who was raised on Dominion Street, also grew up hoping for acceptance. He played baseball and hockey, before he lost enthusiasm for the white-dominated sport at 14.

“It was tough,” Kinch says over the telephone from Kelowna, B.C., where he is a semi-retired bus driver.

“I remember a good friend of ours, Milson Jones, who played (running back) for Edmonton and the Bombers. He was a great hockey player but he said, ‘No, he wouldn’t make it because of the times.’ And he told me don’t bother going any further because you won’t be accepted. So I went to basketball.”

Born to Bahamian parents in England, Kinch came to Canada in 1968.

Slightly undersized at six-foot-one, he earned respect for his breathtaking leaping ability and willingness to bang with the big bodies. He took great delight in beating rival Joe Ogoms, Daniel McIntyre’s six-foot-six star and future Team Canada player, on a jump ball.

Curiously, Kinch’s first interest in basketball was triggered by watching an earlier Daniel Mac star, Ken Opalko, shoot baskets on his Banning Street driveway. Opalko, probably the city’s finest player at the time before going on to a storied university career at the U of W in the late 1970s, was a man ahead of his time.

He was accepting when some other white players weren’t.

“That’s when I started– he let me take shots. And I think that’s when I thought, ‘I’m going to stop playing hockey and I’m going to play some basketball.’ To this day, Ken Opalko is still my hero…” – Carl Kinch

“That’s when I started — he let me take shots,” Kinch says. “And I think that’s when I thought, ‘I’m going to stop playing hockey and I’m going to play some basketball.’ To this day, Ken Opalko is still my hero…”

Opalko’s work ethic rubbed off, too.

“He would see me walk home (from school) in Grade 6 every day and I would see him shoot hoops — practice, practice, practice,” says Kinch. “I thought, ‘Man, this guy’s pretty good.’ He was a giant when I was young.”

The intersection of the Panthers’ lives, however, was more than a mere coincidence.

While immigration from the Caribbean to Winnipeg had been only a trickle in the years before 1962, Toney and Kinch’s parents were part of a bigger wave arriving on the Prairies when Canadian immigration regulations loosened.

The country’s unofficial “White Canada” immigration policy had given way to a new guidelines when Progressive Conservative Ellen Fairclough, the first female federal cabinet minister, obtained cabinet approval for new non-discriminatory immigration regulations.

And so, a trickle became a small stream. Between 1966 and 1980, 4,518 individuals from Caribbean countries settled in Manitoba. Toney’s mom, Helena Liverpool, was one of 487 Caribbean newcomers in 1970. The Kinchs were part of a wave of 322 in 1968. Born in Jamaica, Scarlett was among 247 newcomers from the Caribbean in 1972.

They were unmistakeable targets for racial intolerance. Through his early years in Winnipeg, Scarlett felt the bigotry of his adopted country.

“It was right around that time where they hated blacks, per se, but then the East Indians came and then they had found someone else that they hated more, you know what I mean?” says Scarlett. “It was that sort of racial tension.”

● ● ●

In 1981, a cultural shift was taking place and the tremors were being felt in Winnipeg, too.

Members of Gordon Bell’s Big Six had grown up with R&B music, which would soon transform into hip hop.

The soundtrack of their games — Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight during warmups and Cool and the Gang’s Celebration at the conclusion of wins, many of them blowouts — rubbed some opponents the wrong way.

“It wasn’t to rub it in the other team’s face,” says Sampson. “We’d all gather around in the circle — and it didn’t matter if you were (teammates) Danny Rodrigues, who was Portuguese, or Ray Hartung, or anybody. It would be a Soul Train thing; everybody would do their little dance. And then we just have a good time together, because we knew this was a limited time that we were going to be together.”

Even on U.S. network televisions, executives seemed to be willing to challenge the status quo.

White Shadow, an hour-long drama that ran on CBS between 1978 and 1981, was regular viewing for the Panthers, who were enthralled by the realistic but fictional portrayal of student and basketball life in ethnically diverse Carver High in Los Angeles.

Carver coach Ken Reeves, played by Ken Howard, had the titular role while guiding a team that included Black, white and Latino players.

Gordon Bell players, watching the weekly trials and tribulations of the television cast, felt a sense of connection. Baergen could be compared with fictional Carver star big man Warren Coolidge and the introspective Majors was a fair equivalent of the brainy Morris Thorpe.

And Suffield, when five members of the Big Six were in Grade 11, was a reasonable facsimile of the wisecracking Reeves. A year later, the dashing John Benson, only six or seven years older than his players, slid comfortably into the coach’s seat.

“(Our lives) were just like that, like the show living itself out,” says Scarlett.

“(Our lives) were just like that, like the show living itself out.” – Perrie Scarlett

White team members were also glued to the TV show, including Rempel, their manager and wannabe teammate.

“I watched it, too,” says Rempel, who returned to Winnipeg recently after years of working as a musician and producer in Toronto. “Because it was a reflection of what was unfolding in front of us. I mean, these guys were cool just like those guys were. So much cooler than I could ever be, right?”

Majors, a cerebral guy with an American father, had a unique place in the team hierarchy.

A conduit for the cool music trends his U.S. family connections could provide, he was just as comfortable serving as the dungeon master for the lunchtime crowd at Gordon Bell playing Dungeons and Dragons as he was elevating above a defender before sending a jump shot to the hoop.

“Ron was a quiet guy, but the thing people didn’t realize about Ronnie was, Ron had the mentality of an assassin,” says Sampson. “He would do whatever it took to win and people always saw him as a quiet, shy guy but Ron had the competitive spirit of everybody combined.”

While Majors comfortably straddled the intelluctual and sports world, connecting with popular culture wasn’t without pitfalls, however.

Suffield, who would leave for a head coaching position at Lakehead University in the summer of 1980, was charged with unfairly distributing playing time.

“I was accused by some parents of trying to be like the White Shadow on TV,” says Suffield. “In other words, I purposely started these guys because I wanted to be like the guy on TV.

“I’m sitting there going, ‘No.’ And then I talked to the principal (Herb Lother) about it. I said, ‘What do you want me to do? He said, ‘Just keep doing what you’re doing.’ He said, ‘Varsity athletics is about competition and excellence. These aren’t intramurals.’ ”

The final episode of White Shadow aired on March 16, 1981, five days before the Panthers would make high school basketball history.

● ● ●

They played hard and they probably practised harder.

John Benson realized that soon after replacing Suffield as head coach — the more closely connected his players were, the more likely they were to irritate each other.

Baergen and Sampson, more brothers than best friends, frequently resorted to punches when the temperatures rose.

“They battled each other hard,” says Benson. “Two tough guys. I had to separate them many times.”

Workouts were also a chance for seldom-used subs such as Dan Rodrigues, a five-foot-eight guard who played nose tackle on the football team while his basketball playing time was usually limited to mop-up duty during blowouts. It was the same for other white subs like Ray Hartung, Tom Lepp, Garth Norberg and Tom Papaionnou.

“Practices for me was the time I got to play, and I mean there was no holding back for me,” says Rodrigues. “I went hard and I went hard at them, too. Sometimes they got a little upset with me.”

The template for tough, all-out play had been established years earlier by Suffield; Benson was only happy to continue the tradition.

“Maybe people saw us as football played on a wooden floor, but we could play and we could compete,” says Tony Scott, who played on the ’77 city champions and spent many hours scrimmaging with the next-generation players. “We understood how to play the game at a very high level.

“Before that, I don’t think we were given any of that recognition that we could actually play structured basketball and be successful. Those guys took it to another level.”

At game time, especially at home in Gordon Bell’s cramped senior gym, a rowdy group of students and assorted others cheered their heroes on, stomping on the wooden bleachers and slamming garbage can lids together.

“They walked into the gym and it was an intimidation factor,” says Keith Lynch, an assistant coach on the 1981 team. “Because you had three or four kids on the team that could dunk and, at that time, kids were not really seen dunking like this.”

Since high school games honoured a no-dunking rule in warmups, the Panthers often had to employ subterfuge to get their thrills. Prior to home games, officials were coaxed into a backroom, away from the gym for a pre-game snack.

“We used to try to hide the officials in one of the (phys-ed) rooms so that we could dunk (during the warmup),” says Sampson. “We’d bring them hot chocolate, coffee and pop and stick them in the back room with one of the other PE teachers and we’d get five minutes just to get the crowd excited.”

Without direct supervision, the big four of Baergen, Seales, Kinch and Majors were putting on a crowd-pleasing show for their fans.

The Panthers’ 1981 season was rolling along when they faced the Westwood Warriors in the final of the Festival du Voyageur tournament.

“They were undefeated and we were kind of finding our way — winning, losing and just flopping around,” remembers Westwood star Gord Tucker, who went on to a stellar career at the University of Winnipeg.

“And then some guy in the warmup grabs the mic and says, ‘Hey, we’re waiving the no dunking in the warmup rule.’ And we’re all looking at each other — none of us can dunk. And these guys are going nuts at the other end and we’re looking at each other thinking, ‘Oh, no.’

“But we ended up winning that game and we didn’t see him again until the (provincial) final, so we had some belief that we could beat them.”

The Warriors, coached by the cagey Dave Guss and underappreciated before they went on a late-season run, were one of three teams to beat Gordon Bell that season.

The Panthers also lost to Ottawa’s Bell High School in the final of the prestigious Bedford Roads Invitational Tournament in Saskatoon in January and dropped a 71-68 decision to the Daniel McIntyre Maroons in Game 2 of the best-of-three city final in March.

The Maroons and Panthers had a hotly contested rivalry, meeting seven times that season. At another mid-season game, Gordon Bell romped to a lopsided victory over the Churchill Bulldogs and the home fans weren’t happy about the pounding their team had absorbed.

“I don’t remember seeing any knives but I know there were people waiting outside. They had to call the police down to get us out of the gym.” – Assistant coach Keith Lynch

“We blew the team out and people have words and they weren’t happy with losing and they weren’t happy with how they lost,” Lynch says. “I don’t remember seeing any knives but I know there were people waiting outside. They had to call the police down to get us out of the gym.”

The drama and tension seemed to follow the Panthers.

During a regular-season game at St. John’s High School in January, the Tigers were still smarting from a blowout loss when coach Bill Wedlake had a new plan. After watching University of North Carolina unleash the Four Corners offence against an opponent on television, Wedlake plotted a similar strategy that originated in the 1950s and coached to near-perfection by Tar Heels mastermind Dean Smith.

“For our home games we usually had a half-decent crowd but I think the week before we played them that day we played them in the Wesmen Classic final, and I think we lost by 25 points at least,” remembers Mike Thomas, St. John’s young Black star from that era. “And that’s in the days before the three-point field goal, so 25 points is huge. So athletically, we were just outmatched, you know what I mean? Pretty much at every position.”

In plain terms, the Four Corners offence was an deliberate stall tactic in which St. John’s would look to hold the ball, trying to score on only on the safest of shots. The Tigers scored the first bucket of the game and held the ball for much of the contest and were trailing 25-24 with seconds left.

“Everyone was going crazy because we actually had an opportunity to win that game right down to the last play of the game.” – Mike Thomas, from rival team St. John’s

The gym had been mostly empty at tip-off but news leaked out during night school that a big upset was brewing.

“By the end of the game the gym was packed with people who had never seen us play before or they were just excited,” says Thomas. “Everyone was going crazy because we actually had an opportunity to win that game right down to the last play of the game.”

In fact, St. John’s had the last possession but the upset was not to be.

“If you ever want to watch that movie Hoosiers, there was a play called the picket fence,” says Thomas. “That’s what we ran, an out-of-bounds play… a guy went wide open and did a finger roll instead of a layup off the backboard and it rolled around and fell off the rim at the buzzer.

“To this day if you mentioned it to that guy, he’ll want to fight you. It was that big of a deal.”

● ● ●

Gordon Bell reached the provincial final on March 21 with a 44-3 record only to meet an old nemesis, the Westwood Warriors.

The drama began before the opening tip-off.

As the No. 1 seed, the Panthers were the home team and, according to provincial guidelines, required to wear their white jerseys. Some Panthers claim to this day they had only one set of uniforms, a dark purple-and-gold set purchased the previous year. Sampson, however, admits the team had a set of whites, but inexplicably didn’t bring those jerseys to the final game, except for Scarlett.

The referees insisted; Warriors coach Dave Guss insisted. After a lengthy discussion and the threat of multiple technical fouls if they played in their dark uniforms, Benson was given the option of having his team play with practice jerseys provided by the U of M or Westwood’s home whites.

They chose the Westwood home whites, which set up the preposterous spectacle of two teams in Warriors uniforms playing each other. Only Scarlett — with his white Gordon Bell jersey — looked the part.

“The thing that annoyed people was the fact that OK, if this is a true team sport, they could have said, ‘Listen, we’re just gonna wear our whites. You guys just wear your darks…. It turned into something that didn’t need to be,” says Sampson, who moved to Vancouver in 1993 and works for the B.C. government’s First Nations Health Authority. “For us, it was just another bump where we all just got together and said, ‘OK, there’s one more (obstacle) in front of us. Let’s go jump over it.’”

The Panthers, apparently rattled, started slowly and were never able to find the running game their reputations were built on. Sampson, a superb scorer and playmaker, had perhaps his worst game of the season and finished with only three points.

Gordon Bell led 28-27 at halftime.

Baergen, the tournament MVP, led all scorers that night with 17. Majors had 15 and Kinch, Scarlett and Toney had six apiece. The unflappable Scarlett’s two free throws with four seconds left on the clock provided the margin of victory.

Before Baergen’s death, the Panthers would sometimes get together to reminisce about the glory days.

“We’ve often said when we’ve gotten together we should have our 20-year reunion game, and now it’s like, ‘I can’t run up and down the court,’” Sampson says with a laugh. “Now it’s, ‘Let’s just have a three-on-three game on one basket.’ ”

Apart from the old newspaper clippings, the flickering YouTube video and fading memories, the only other reminder of the Panthers’ historic feat is a small piece of silver metal — engraved with “Gordon Bell 1980-81” — on the base of the trophy that is awarded to Manitoba’s high school boys’ basketball champ.

But there are some who insist the Black Panthers are worthy of a more permanent honour, that they should be included among the game’s greats in the Manitoba Basketball Hall of Fame. The hall, however, tends to only recognize teams that had multi-year dynasties.

Tony Scott, one of Gordon Bell’s Black star players who preceded 1981’s mythical six, says it’s an oversight that needs to be corrected.

“There was never before that many minorities playing on a team that dominated in the province they way they did,” says Scott from his home in Port Coquitlam, B.C.

“Never ever had we seen anything like that. I mean, do we have to establish a Black Hall of Fame? No, you don’t want to do that. The fact is, these kids were inner-city kids who were a special group that happen to have that type of makeup and that was never replicated anywhere in the province. That was something quite unique in that time frame.”

Although they may not be in the Manitoba Basketball Hall of Fame, Toney, Scarlett, Majors, Kinch and Sampson are fiercely proud of their legacy.

They were trailblazers and innovators then. They are good men now.

mike.sawatzky@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @sawa14

Mike Sawatzky

Reporter

Mike has been working on the Free Press sports desk since 2003.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.