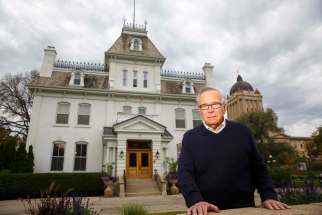

Triumphs and tribulations Former Manitoba premier Gary Filmon takes stock of political rise and reign in memoir

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/09/2021 (1637 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Gary Filmon came close to quitting as the leader of the Progressive Conservative party before he became premier in 1988.

It wasn’t the pressures of political life or the frustrations of being in opposition for five years that proved difficult for the son of a Polish immigrant, who grew up in relative poverty on the mean streets of Winnipeg’s North End.

It was the persistent attacks from his own caucus that almost did him in.

“I had had enough,” Filmon wrote in his recently released memoir titled Yes We Did: Leading in Turbulent Times. “I was prepared to resign.”

Lessons in leadership

Posted:

Read excerpts from Gary Filmon’s newly released autobiography Yes We Did: Leading in Turbulent Times. They touch on themes that remain today in Manitoba and across the country — the fragility of leadership, governing in a time of crisis, and navigating the campaign trail.

Filmon won an acrimonious leadership battle in 1983 after former Tory premier Sterling Lyon lost the 1981 general election. Like many leadership contests, it was divisive. But unlike most, the bad blood lingered for years, well beyond what it normally takes for a party to heal.

There was an anti-Filmon faction in caucus — led by influential Tory MLAs Clayton Manness (who ran against Filmon for leader), Don Orchard and Jim Downey — that just wouldn’t go away. It nearly caused Filmon to throw in the towel.

“As the months progressed, Manness, Don Orchard, Gilles Roch and Jim Downey took every opportunity to undermine and embarrass me,” wrote Filmon, 79, who’s been working on his book for the past five years.

Even after the 1986 general election, when the Tories came close to defeating the NDP government under then-premier Howard Pawley, the political infighting continued.

“My own situation did not improve, as the dissidents in caucus continued to stir up discord, seeking every opportunity to demonstrate a divided caucus,” wrote Filmon. “My frustration continued to get the better of me as I’d chat in the evenings with Janice (Gary’s wife Janice Filmon, current lieutenant-governor of Manitoba) and question whether or not it was worth it to continue battling the likes of Orchard and Manness.”

Filmon called for an immediate leadership review at a party convention in 1987 after rumours circulated some were plotting to remove him as leader. He won the review with 70 per cent support and went on to form a minority government in 1988.

It was a rough start in what turned out to be a successful career in politics for Filmon, who won majority governments in 1990 and 1995.

“I guess what kept me going was that I honestly believed that there was a role and a responsibility for me to do the things that needed to be done,” Filmon said in an interview with the Free Press. “To turn it over to people who were just using power tactics and undermining my role, that was not the kind of people who should be leading in these challenging times.”

Many of the dissenting MLAs — Manness, Orchard and Downey — would become senior cabinet ministers under Filmon, who appointed them against the advice of senior advisers. Downey became deputy premier and was one of the most influential members of Filmon’s cabinet.

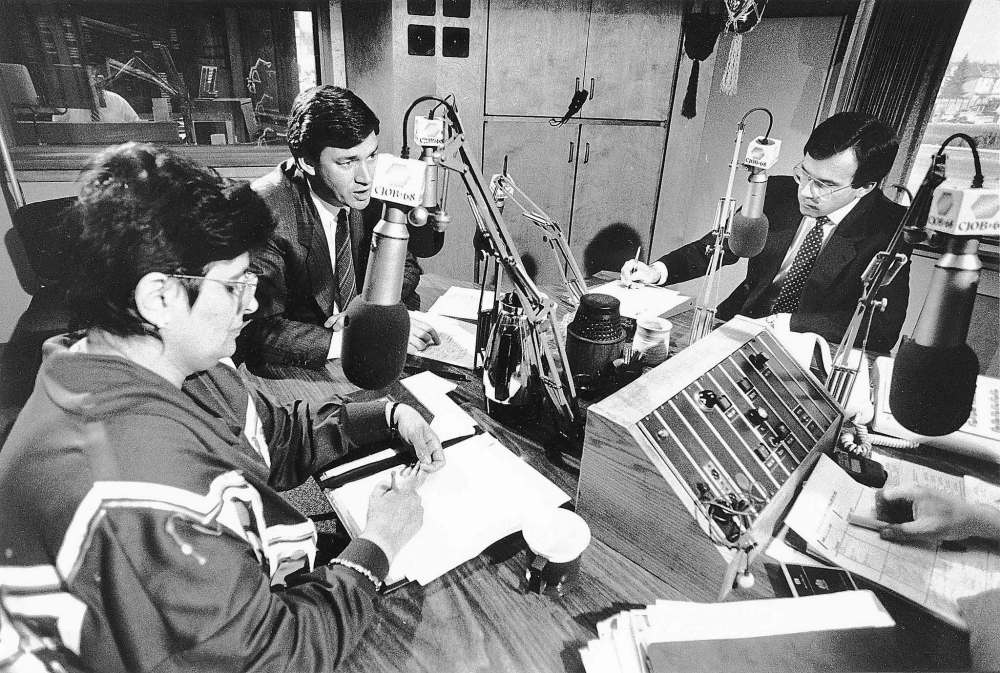

Leading in Turbulent Times takes the reader from Filmon’s early childhood in Winnipeg’s North End to his days at the University of Manitoba where he studied engineering, worked in the industry for a few years and eventually took over his father-in-law’s business college. After a short stint on Winnipeg city council, Filmon made the jump to provincial politics and became party leader within four years. It was a quick ascent up the political ladder.

Filmon’s insight and behind-the-scenes stories around the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords is one of the highlights of the book. Canada’s political landscape in the late 1980s and early 1990s was dominated by constitutional wrangling, as Ottawa and the provinces attempted to bring Quebec into the constitutional fold.

Book launch schedule

Brandon

Sept. 22, 6:30-8:30 p.m., Riverbank Discovery Centre

Gimli

Sept. 25, 4-6 p.m., Gimli Yacht Club

Winnipeg

Oct. 26, 7 p.m., McNally Robinson Zoom launch

Filmon was thrust into it immediately after becoming premier in 1988. It became all consuming during his first four years in office, including marathon first ministers meetings, political compromises and a piling on of demands from all quarters of the country. The public was burnt out on all things constitutional. By the time the Charlottetown Accord was presented to Canadians after the failure of Meech Lake, the proposed constitutional changes became so complex, it was almost impossible to explain their merits.

“It was like playing whack-a-mole — whenever you answered one criticism, up popped another,” wrote Filmon. “It was impossible to explain the balance and the trade-offs that made Charlottetown a reasonable solution, because you’d have to spend an hour going through a carefully reasoned conversation… the opponents just boiled it down to a few sound bites that riled up their audience.”

Charlottetown was rejected by Canadians in a 1992 national referendum, an approval process Filmon says he laments to this day.

“In the end, a referendum is a terrible way to make important government decisions. I wish we had experienced Brexit before Charlottetown,” he wrote. “Government by referendum does not work.”

There was a silver lining: the close bonds created between premiers during Meech and Charlottetown lasted long after the final referendum ballots were counted. Filmon developed close friendships with several of the key players, including Saskatchewan NDP premier Roy Romanow and New Brunswick Liberal premier Frank McKenna (whom he sent a copy of the book’s manuscript for input).

Filmon said he and other premiers regularly consulted each other on issues after Charlottetown and would sometimes co-ordinate government policy. When Manitoba converted pharmacare coverage to an income-tested program, for example, it was done at the same time as Saskatchewan to show it wasn’t ideologically motivated.

The book covers most of the hot-button issues during the Filmon government years, from balanced budgets, health-care reform and the save-the-Winnipeg-Jets campaign, to the 1997 Flood of the Century and the privatization of the Manitoba Telephone System.

Like most books written by former politicians, Filmon spends a lot of time defending his government’s record. There are no apologies in the 280-page memoir; nothing the former premier reflects on that he would have done differently.

Some of it is a rehash of old political battles, deep wounds that will probably never heal. The partisan brawls over health-care reform, especially the often sensationalized “hallway medicine” and “frozen hospital food” sagas, still appear to be a thorn in Filmon’s side, who points out his successors were unable to do any better than he did.

“After 15 years of NDP government, Manitoba still had hallway medicine, overcrowded ERs, and among the longest waiting lists in Canada for most procedures,” he wrote.

Filmon attempts to explain why he blamed flood victims during the 1997 flood for “building on a floodplain,” and how some “tried to game the system” by tossing furniture into their flooded basements. On the privatization of MTS, he said he never promised Manitobans that he would not sell the Crown corporation, despite claims to the contrary by his political opponents.

(It is true, he never made that pledge. The closest Filmon ever came was on May 24, 1995 when he said in the legislature that “we do not have any plans” to privatize the Crown corporation, but that his government would “keep an open mind on all opportunities that are presented to us.” A year and a half later, the Tories announced MTS would be sold off.)

Cabinet making is one of the toughest and loneliest jobs for any first minister. For Filmon, one of his most difficult decisions was to exclude longtime Tory MLA Harry Enns from his first cabinet. The rural MLA, who died in 2010, served in Tory cabinets dating back to former premier Duff Roblin. He was a seasoned politician and a strong supporter of Filmon, but he also suffered from untreated alcoholism. Filmon couldn’t have him in cabinet until he dealt with his drinking problem, which he did following an impaired driving charge.

“Enns went away to an addictions treatment centre and shortly after his return, I appointed him to cabinet, where he served with great effect for more than a decade,” Filmon wrote, calling Enns an “icon.”

Manitobans never knew it at the time but Gary and Janice Filmon came very close to being victims of a plane crash, just a few weeks after Janice underwent treatment for breast cancer in 1989. The couple were flying back to Winnipeg from Dauphin (where Filmon had a speaking engagement) in a small aircraft when one of the landing wheels wasn’t fully extended. The young pilot had to circle around the control tower in Winnipeg so officials below could visually verify how many wheels were down. They could see all three, but the indicator light still showed one wheel was not down. It was possible one of them was not locked into place. The Filmons were given instructions to assume a crash-landing position.

“We dutifully followed instructions, assumed the position, held hands tightly, prayed together and waited for what seemed an eternity,” Filmon wrote. “In an instant it was over. We landed safely.” The story was never reported in the media.

Filmon devotes considerable space in his book to Janice (who he says deserves her own book), how he “married up” when they tied the knot and how influential she was throughout his political career. Janice, now in her seventh year as lieutenant-governor, played key roles in inter-governmental relations, including during trade missions when Canadian premiers travelled abroad to promote bilateral trade.

No book on the Filmon years would be complete without a chapter on the Tory vote-rigging scandal. Filmon doesn’t shy away from it. It’s a black mark on his government’s record, which saw senior party officials secretly fund three Indigenous candidates in rural Manitoba during the 1995 provincial election. The goal: to split the vote with the NDP.

“I was disappointed in everyone involved in that,” Filmon said in an interview. “It was clearly wrong. It was a foolhardy expedition.”

There was no evidence Filmon knew anything about the scheme, the details of which weren’t revealed until three years later when a CBC reporter convinced one of the Indigenous candidates, Daryl Sutherland, to tell his story. The plan was hatched by several Tory strategists, including Filmon’s chief of staff Taras Sokolyk. Filmon said he decided to testify at the inquiry in 1998 because he felt it was the only way to convince the public he had nothing to do with it.

“It was gruelling,” said Filmon of the six-hour grilling, including by NDP lawyer Mel Myers. “I firmly believed that the only way the public would really be satisfied was if I testified under oath, so I did.”

Filmon doesn’t name Sokolyk or Jules Benson, head of treasury board secretariat at the time, in his book. Sokolyk took $4,000 from the PC party fund to bankroll the Indigenous candidates; Benson tried to help him cover it up by returning the money and fudging the party’s books.

Filmon says he has spoken with Sokolyk many times since the inquiry, including in social settings.

“I don’t think things like this, which is an error in judgment, should be a detriment to a person being able to have a normal life and a productive future,” he said.

No one can be certain, but the vote-rigging scandal could have been the final straw that knocked the Tories out of government in 1999. It wasn’t the only tough issue facing the PC party at the time. Hallway medicine and health-care reform weighed heavily on the minds of voters and selling off MTS without a mandate was also seen as unforgivable for some voters. Still, with the economy growing at a steady pace, the books balanced and Manitobans enjoying modest tax relief, Filmon had a chance.

“I had lots of reasons why I should have stepped aside from my own personal standpoint which was, I could have been getting corporate appointments and all manner of different offers because of my experiences and my time in office,” Filmon said.

The party’s internal polling showed the Tories could still win with Filmon at the helm. They came close, losing 32 to 24 in seats to the NDP, but only four percentage points behind in the popular vote. Seven ridings were won by fewer than 300 votes, including four won by the NDP.

“I worked harder in that election than I had in any of the previous ones that I had won,” said Filmon. “But it just wasn’t meant to be.”

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.