Bertha Rand: Winnipeg’s cat lady Famous protector of felines fought decades-long battles with neighbours, police and the limelight

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/05/2021 (1682 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

1. Well, it looks like we’re at it again

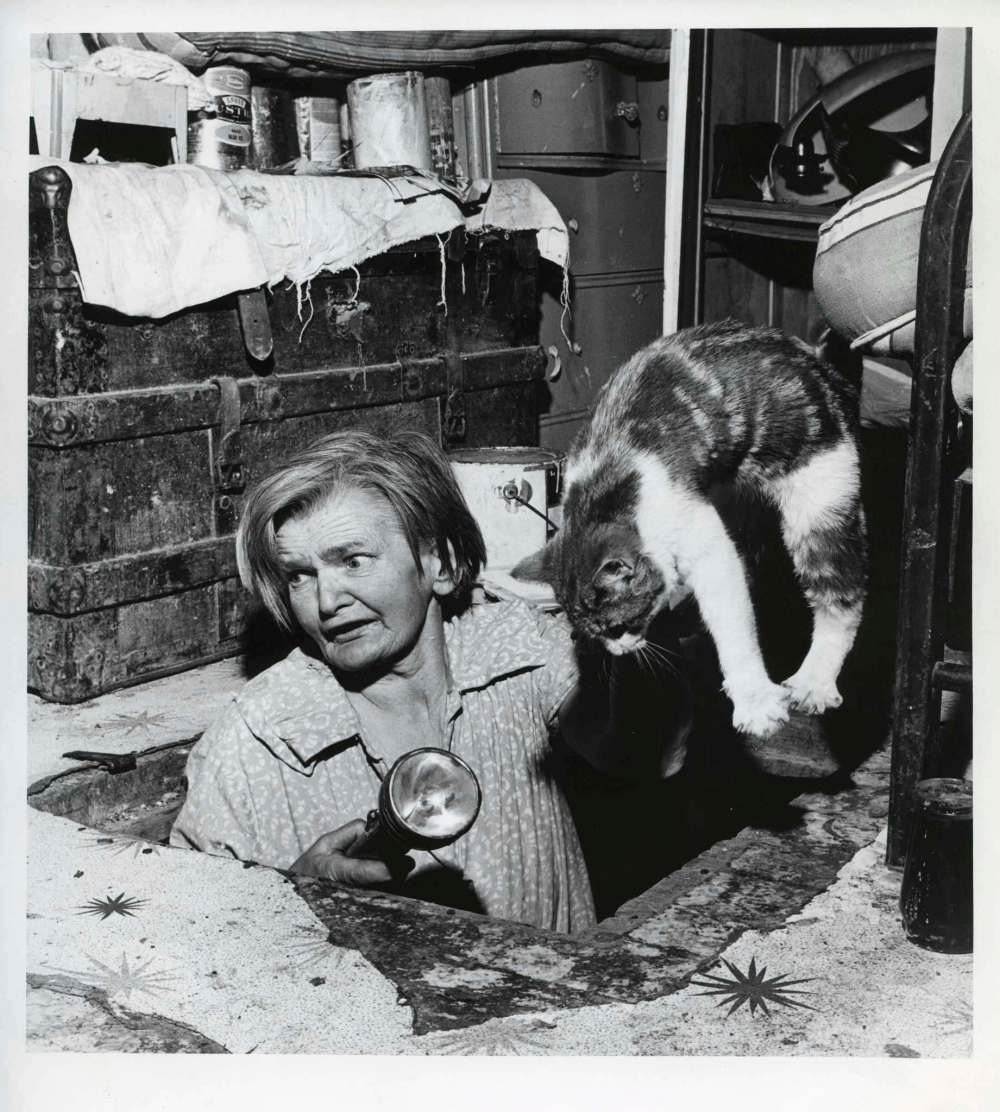

She stood in the doorway, frowning, with a black cat tucked over her arm and five others flopped down beneath the shade of a tree in the front yard of her house on Queen Street in St. James. In the backyard, a few kittens mewed as they lay in the sun. Inside, 15 sets of paws awaited their guardian’s return.

A sign on the front door asked in capital letters that agents and pedlars skip over the house, and a large board propped against the tree, just past a picket fence spanned by chicken wire, reiterated the message.

Bertha Rand, three weeks shy of her 73rd birthday, didn’t want to be bothered. She wanted only to be with her cats, many of whom were left at her doorstep or tossed into her yard by strangers who knew that no cat would ever be turned away.

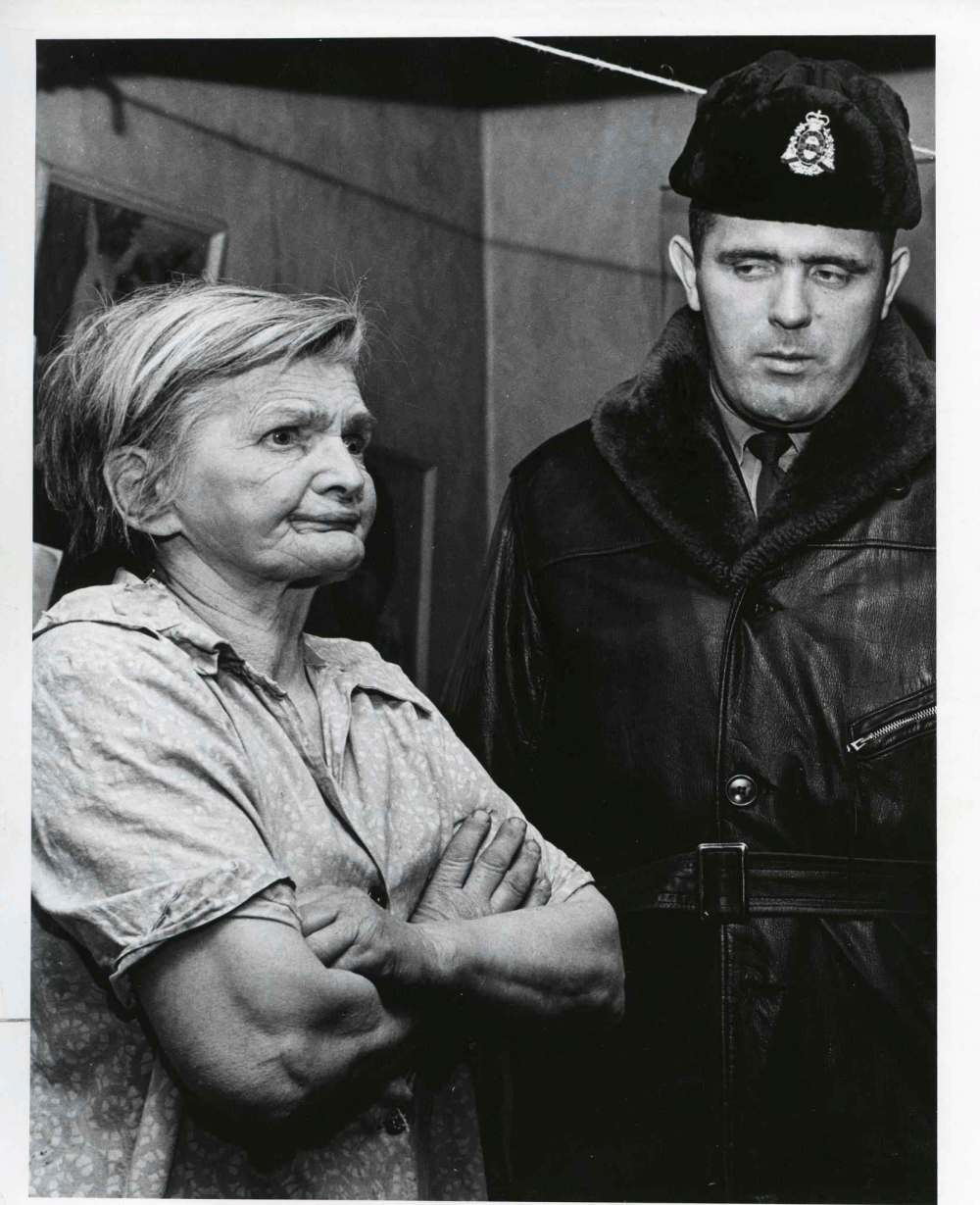

Those signs didn’t work. That morning, George Maltby, the police chief of St. James, knocked on the door and handed her a summons, charging her with a crime that could be at best described as one of compassion and at worst one of compulsion: she had too many cats, and was in contravention of a City of St. James bylaw, Bylaw No. 10640, which said no more than three animals of the same species could legally reside in any home within the city’s limits.

The bylaw existed because Bertha Rand did, or rather because her neighbours noticed she did.

A committee made up of Queen Street residents took it upon itself to go straight to city hall. The neighbours complained the menagerie was depreciating property values, that the growing number of cats presented a potential health nightmare, that the smell emanating from Rand’s house was too putrid to go uncontrolled, and that the cats themselves would be better off elsewhere.

The council of St. James, led by Mayor A.W. (Bill) Hanks, enacted No. 10640. Colloquially, it became known as the Bertha Rand bylaw. Rand was charged with violating a previous version of the bylaw earlier in the year, but those charges were dropped.

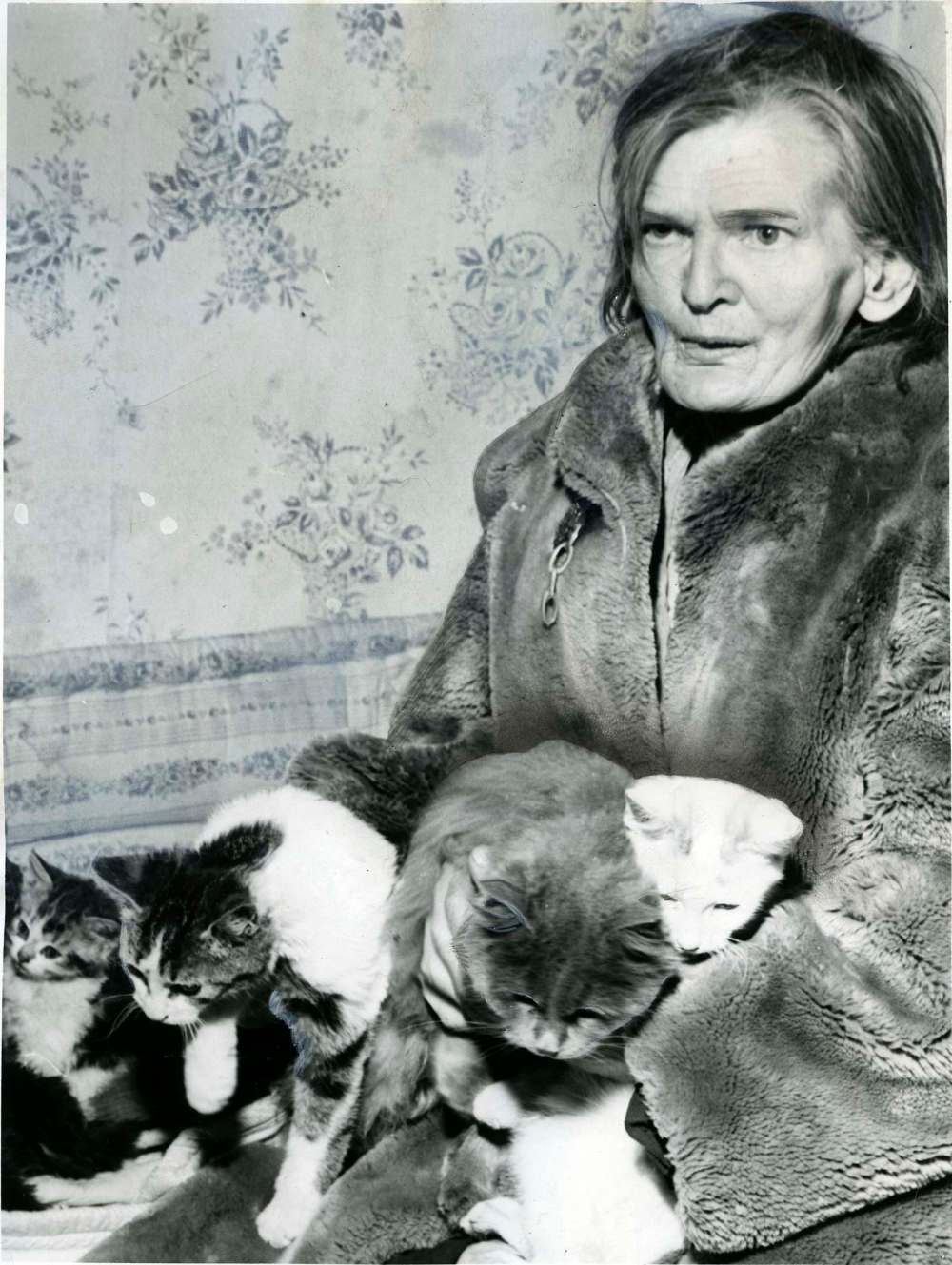

It must be said that Bertha Rand was a very famous woman without ever trying to be, an accidental celebrity embraced and abhorred by a public that cast her as an eccentric, a kook, a miscreant, an activist, a spinster, a witch, a defender, a spectator sport, a rebel and an urban legend who very much existed.

Headlines referred to her simply as “Bertha,” hold the Rand, and whenever police came knocking, as they did that morning in June 1967, after a short-lived victory in court six months before, a horde of reporters followed, looking to hear from a woman who probably wished they’d never learned her address was 350 Queen St.

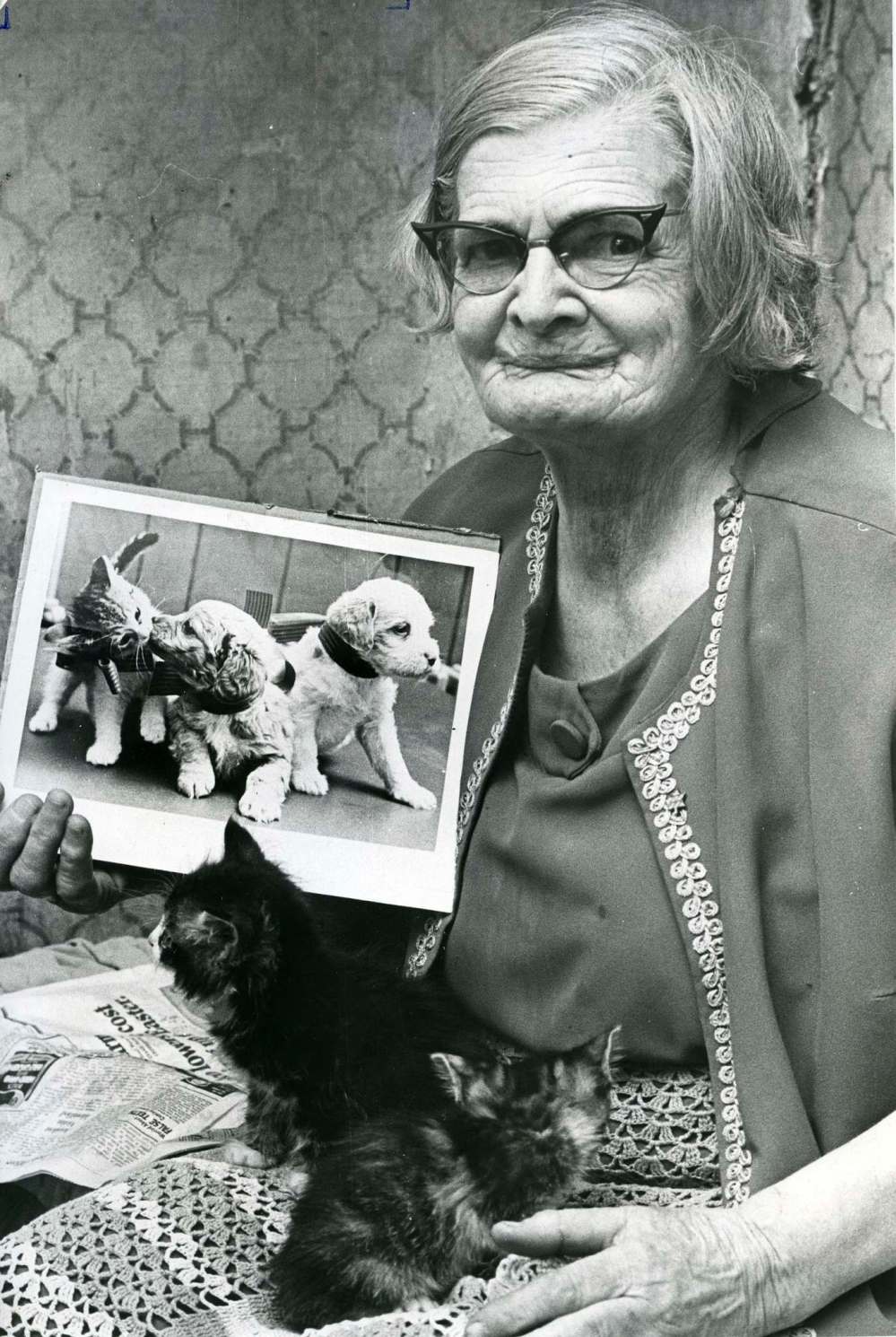

One reporter knocked on her door and stepped back. With a black cat slumped over her forearm, Bertha Rand stood in front of her house, cat-eye glasses resting on her nose, as she came to a realization that her war — with the city, with her neighbours, with the press, with strangers, with her own mind — was not yet over, not in any way at all.

“Well,” she said. “It looks like we’re at it again.”

2. Crystal City days

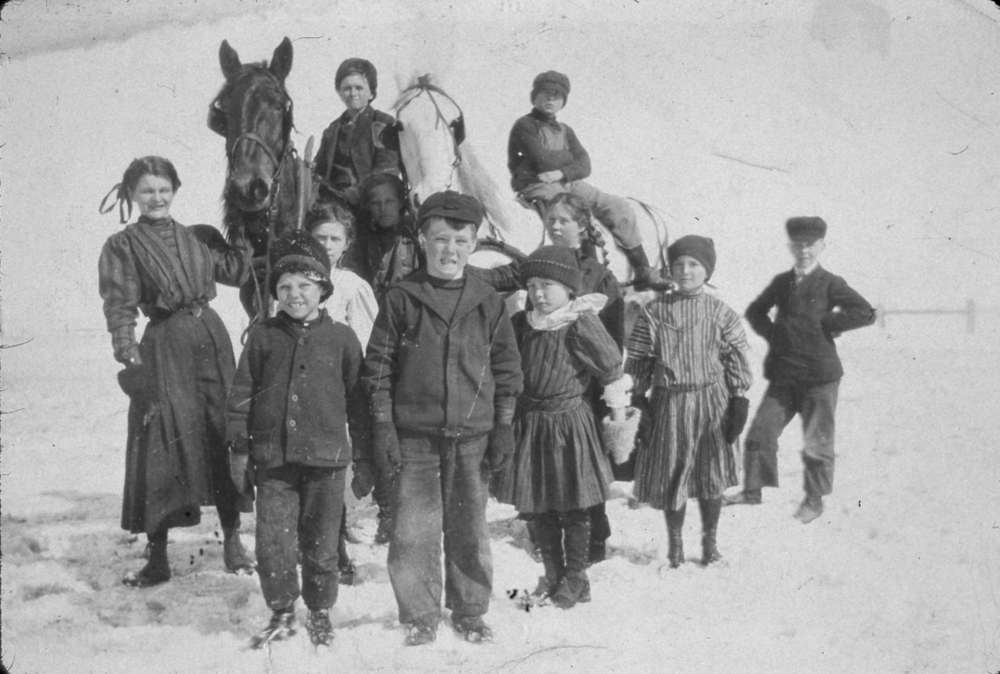

Bertha Gertrude Rand was born on the first day of summer in 1895, the fifth child of Silas and Sarah Rand, who owned a homesteading farm a few hours southwest of Winnipeg.

Silas and Sarah were fruitful, and multiplied. By 1909, there were 11 Rand children — William, Ethel, Orinda, Florence, Bertha, Lyman, Sarah, Esther, Eunice, Dawson and Stanley — all packed into a small log house with one room surfaced by a dirt floor about 10 kilometres south of Crystal City, which was hardly a city. The Rands weren’t privy to many crystals, either.

Their life was not idyllic, but it was a life nonetheless, one filled with hard work and an interdependence characteristic of a farming family. Each Rand had a role to play. For Bertha, a regular task was preventing cows and horses from making their way into neighbouring fields of corn and grain, where they could trample a family’s future with a brief stampede.

Once, her sister Esther said, a teenage Bertha mounted a horse and chased after several, screaming at them to come back at once.

“My mother didn’t tell me too much about Bertha, but that’s one story she would tell,” says Esther’s daughter Lorraine Hagen, now 81 and living in British Columbia. Her mother died in 2000 at the age of 99.

For however much is known about Bertha’s later life in Winnipeg, details of her years in Crystal City — her origin story — are comparatively scant, even to her family.

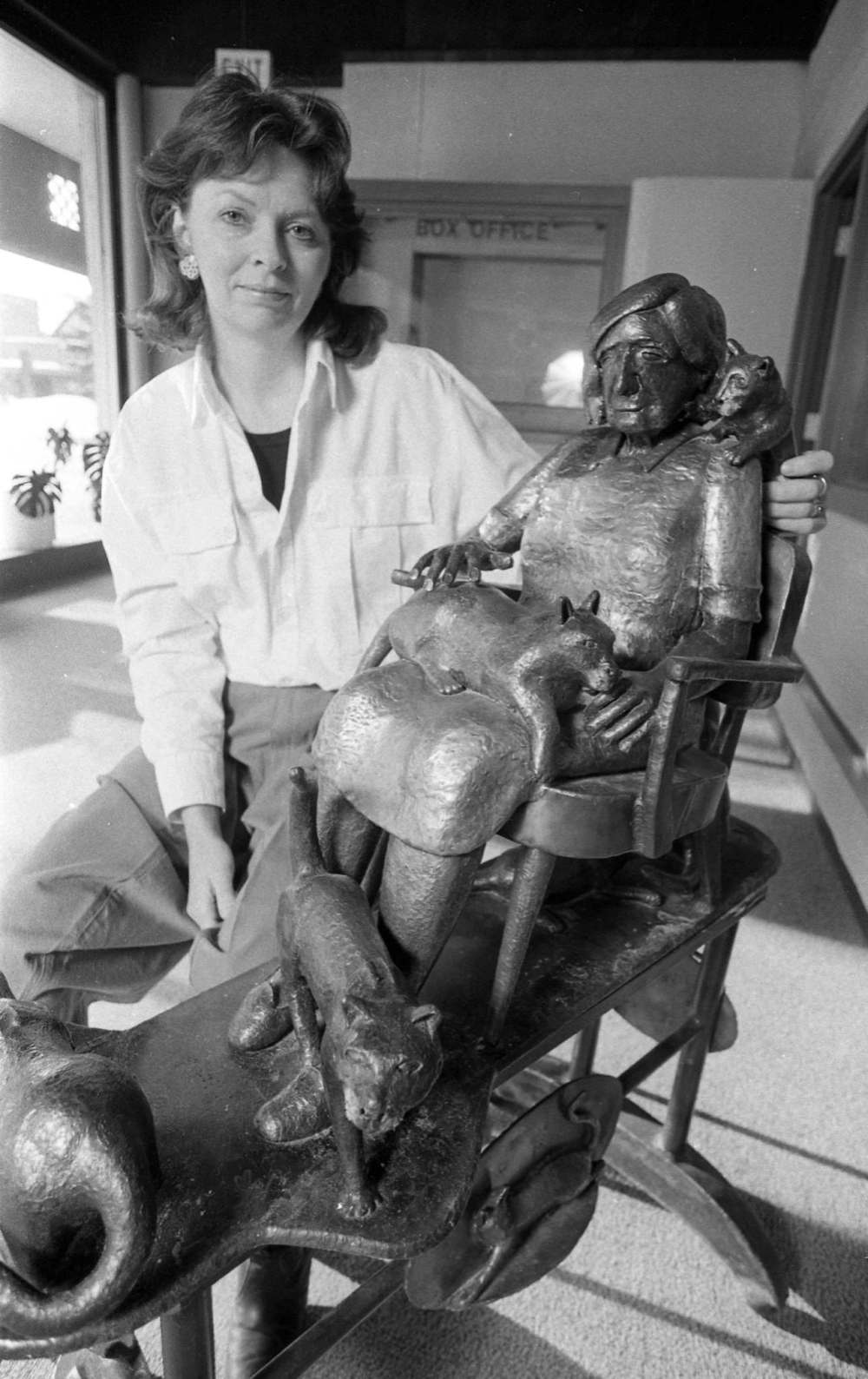

Maureen Hunter realized this in 1987, when she was writing a play about Rand, entitled The Queen of Queen Street. Hunter knew the rough contours of the life that would soon consume her research, but the raw material, the details that change a play from a collection of scenes into a fully realized vision, was missing. She needed to understand the lady before the cats.

She got in her car with a friend and drove south from Winnipeg to Crystal City, roughly 50 years after Rand took a ride in the opposite direction. Armed with a notepad and tape recorder, Hunter, a former journalist turned playwright, set out to find a link to her subject. She also adopted a cat, named Ben, to get into Rand’s psyche.

Like a good reporter, she went to the seniors centre, hoping to connect with somebody old enough to remember the town’s famous expatriate. Her instincts paid off: Pat Simning, a woman who grew up around the same time as Bertha and her siblings, was still alive, and reached back into her memories.

She told Hunter about the house with the dirt floor, about the brothers and sisters who played the fiddle, about Bertha’s prowess on the skating rink. She also gave hints at the tragedies that would soon befall her.

Ethel died in 1913, at the age of 21; Florence died the following year at 20. In just over a year, an 18-year-old Bertha’s two older sisters were taken from her. Then came the war. Her brother Lyman went off to fight in Europe, and returned a hero short one leg.

The war, the loss and the oncoming Depression spelled trouble for the family farm. Silas died in 1920 at the age of 71, with Orinda following two years later. Simning told Hunter the family believed Silas had buried money in the fields, which were bought by her uncle.

From time to time, Bertha and her mother returned with shovels to see whether the story was true. With the Depression soon to be in full swing, and no farm to work on, Bertha got a job as a “scrubwoman” at the local hotel, earning $5 per week with her sweat and sore elbows.

This information, though second-hand, helped Hunter build a narrative that was missing from a story everyone in Winnipeg thought they already knew. All that the public, and the press, did was discuss Rand’s current life.

In Crystal City, Hunter found at least some inkling of Rand’s roots as an independent woman who scrapped for all she had, who wasn’t willing to let anyone take anything, or anyone, from her again.

That story corresponds with what little information Hagen has about her aunt, whom she only met a handful of times. But there was one other tale of Crystal City heartbreak that neither Simning nor Hagen knew.

There was a story that while Lyman went off to war, so did another local man whom a teenage Bertha was dating, or possibly engaged to marry. He’s said not to have returned. “My mother said she was basically heartbroken,” says Hagen, who admits she knows little about this moment in time.

In 1933, Lyman died at the age of 36. With no undertaker in town, Simning recalled to Hunter, his body was transported by train to Winnipeg. Bertha chased after the train on foot, watching another person she loved — her baby brother — leaving her behind.

The story handed down to Hagen from her mother may have been true, but there is no record of such a loss or any broken engagement. What is clear is that Bertha Rand’s life changed. From the death of her sisters onward, through the death of her father and brother, and her surviving siblings’ moves to Winnipeg or elsewhere, her inner circle contracted, while she stood, at the middle, reaching out.

Proof of a lost love in the Great War doesn’t readily exist. There is, however, a letter, in the Winnipeg Free Press, published Dec. 6, 1939, that marked the first appearance of Bertha Rand’s words in the newspaper that would one day publish more than 200 articles about her exploits, making her private life the matter of heated public discourse. This is the letter in full:

“SOCK — In loving memory of Karl Sock, who was drowned, December 3, 1935. Today I am thinking of someone, Who was loving, kind and true. Whose smile was as bright as the sunshine. That someone, dear Karl, was you. How often you came before me, Your dear face fond, and true. For death can never take away, Sweet memories, dear Karl, of you. — Sadly missed by Bertha Rand”

3. Big city Bertha

The apartment on Kennedy Street was small, but it was hers. It was 1936, and with fewer reasons to stay in Crystal City, she had made the decision to move to Winnipeg.

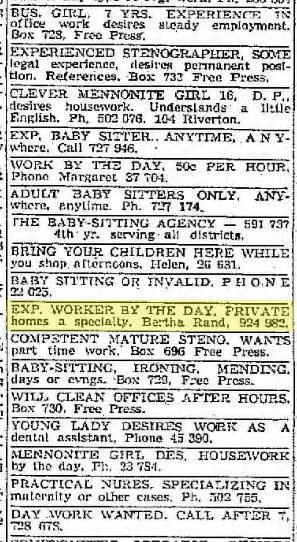

She placed paid advertisements in the newspapers promoting herself as a day labourer, working whatever jobs she could to earn a steady income — a commercial scrubwoman, as she had been in Crystal City, and a cleaner for residences much ritzier than hers.

Her brothers were all in Winnipeg by then. Her sisters were spread out: Eunice in St. Vital, Esther in Transcona and Sarah still at home in Crystal City. Her siblings were all married, making Rand, 41 years old, somewhat an outsider in her own family.

Her advertisements were published in spurts, and she soon had a relatively stable rotation of clients at downtown offices and nearby homes. It is believed that she lived alone.

She was a frequent entrant in weekly trivia competitions in the newspapers, winning a dollar in 1936 for correctly guessing that the daily picture puzzle was a mop. Wherever she was, the radio was turned on. She often listened to multiple sets at once, not wanting to miss a single word or contest. What to some people was background noise was, to Rand, a partner in conversation, a constant stream of connection to a city that had just become her own.

Eventually, Rand moved to an apartment on Donald Street, described to Hunter by a radio repairman whom Rand hired in 1947 as a place “about as big as a closet.” The setting was characteristic of every place she’d lived before and any place she’d live after. When she was on the job, her clients’ radios were flipped on, and if they were broken, she’d make a call for a repair herself.

On New Year’s Eve in 1946, Rand was onstage at a packed Metropolitan Theatre, competing in the weekly Winnipeg Tribune trivia contest, where questions like “What Manitoba natural resources boomed in 1946?” and “Who was the late king of Italy?” were tossed out by CKY MC Tommy Benson, with cash prizes on the line.

The first question she faced she answered correctly, winning $2. But on her “Front Page Special” — with $50 just one correct answer away from her pockets — she stumbled.

“What is the name of the Canadian minister of labour?” Benson asked. “McKinnon,” Rand responded. “Sorry. It’s Humphrey Mitchell.”

That money would have gone a long way. As a woman in her early 50s, Rand continued to do difficult manual labour, carrying her mop and bucket around the downtown from job to job, and by most accounts, lived her life with few frills or extravagances.

She was thrifty, shrewd, and without much choice in the matter, fiercely independent. With her meagre income and a small insurance payment, she was able to save up $1,500 — enough to buy a home in which she could live out her remaining years.

She settled on a house on Queen Street.

4. The queen

For better or worse, everybody knew where Bertha Rand lived.

There was a short period when her eccentricities were unacknowledged in the working-class neighbourhood of St. James, where she was far from the only person living a life within her means. It was a blue-collar neighbourhood. The houses around hers were just as small. Before she stood out, she blended in.

But soon came the cats. There were at first three or four, then five or six, then 13 or 20. The number varied depending on the going estimate of the day, a yardstick that for many who never spoke to Rand indicated her mental well-being.

Before she was of concern to their parents, Rand became an object of fascination and intrigue to neighbourhood children. They’d go by her house to catch a glimpse of her and try to get an accurate count of cats; some would throw stones at her windows, calling her a witch. When they broke, she’d patch them up with cardboard. A walk past Bertha Rand’s house became a guaranteed source of entertainment.

“Let’s go to Bertha’s; I have to collect for the paper,” said Charlie Caswell to his friend David Bayn before leaving on his weekly route in 1964. “He asked me if I wanted to see something,” recalls Bayn, now in his 70s. “So we went.”

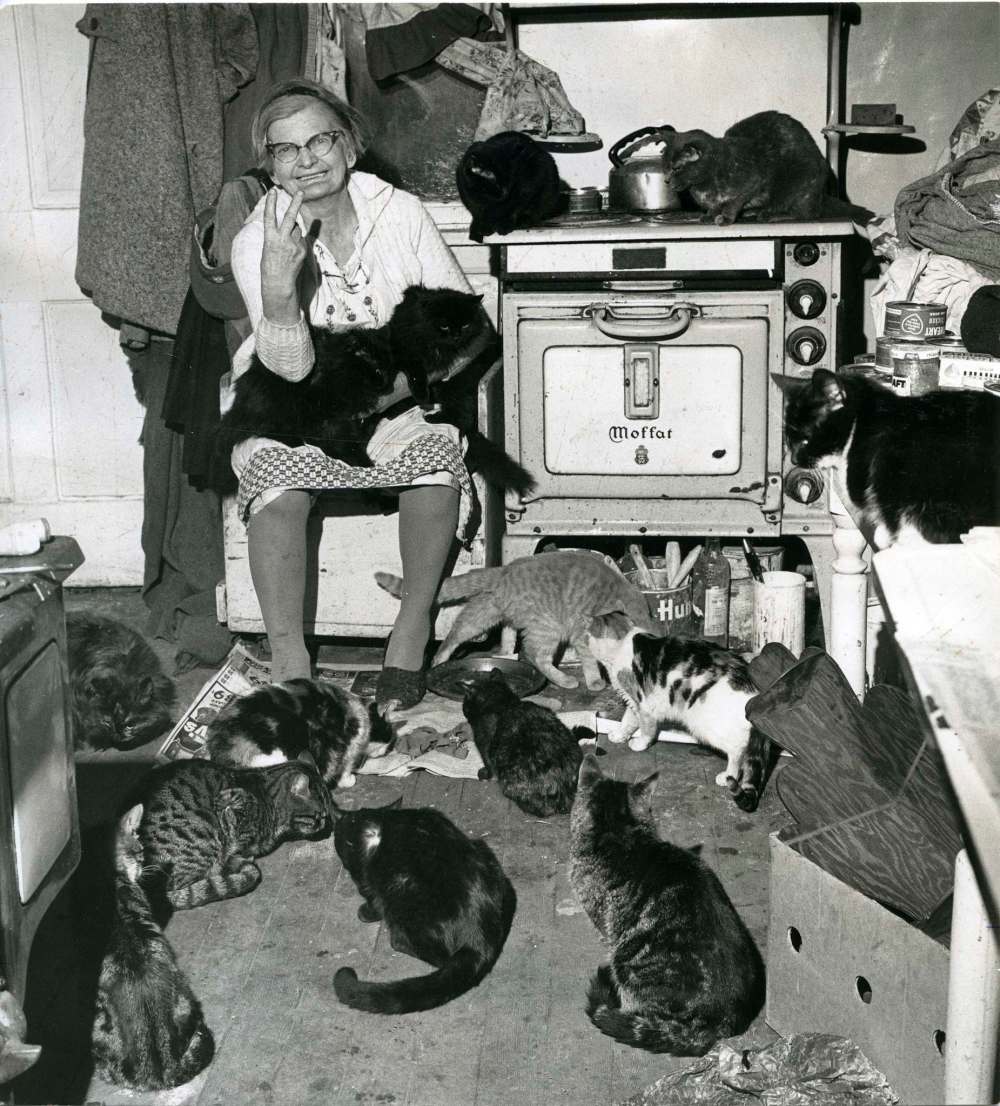

The house was dirty and cluttered, with cats crawling on every floorboard and across every shelf, counter and table. On the dining room table, there was a plate of cat food left out for the animals to nibble at as they pleased. “The place was alive with cats,” says Bayn.

That was only partially Rand’s fault. She started off with a few, but her infamy and care for street cats soon drew unexpected donations on her doorstep of litters of unwanted kittens in baskets or elderly cats who otherwise would die in alleyways and dumpsters. Sometimes, people would throw cats over the wire fence that surrounded the house. It was not in Rand’s nature to not nurture; she couldn’t turn them away.

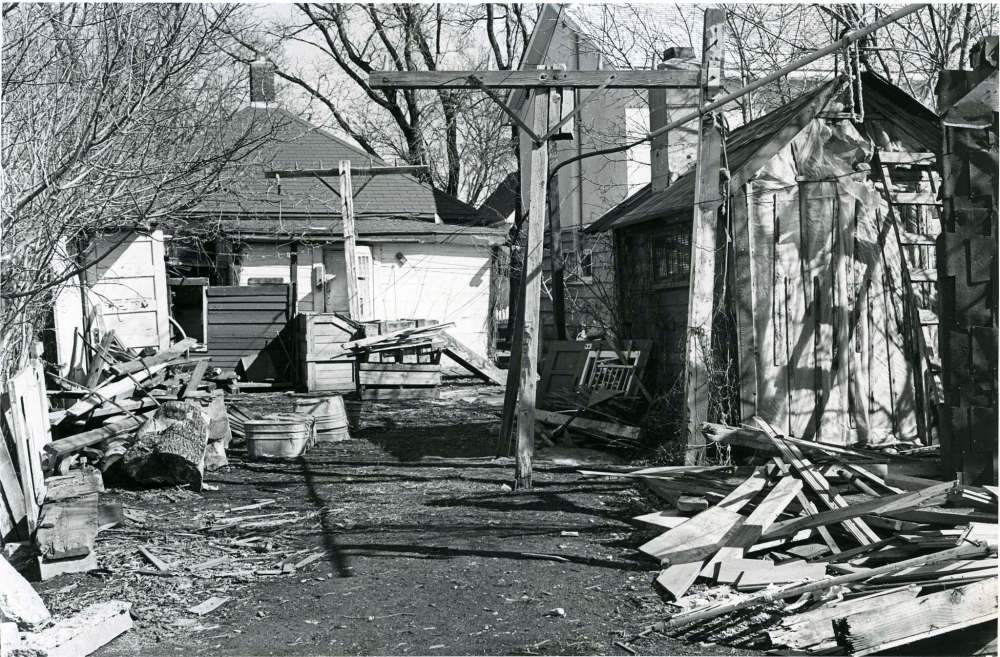

Her cats became the focal point of her existence, willing recipients of her care, with personality traits — independence, sensitivity, protection, tenacity — that mirrored her own. Rather than paying for traditional heating, Rand walked the back alleys of St. James with a wheelbarrow, hauling loose boards and lumber that she could chop in her yard and light in her wood-burning stove. Most of her finances and pension went to her furry beneficiaries.

The way she saw it, there was no alternative. If she didn’t take care of the cats, they would get sick and die on the streets, run over by careless drivers and left suffering on the side of the road. Or, they would be taken to a shelter, like the Humane Society, where at the time, they were more likely to be put down than live.

“She was, in her way, providing what solutions were available to her at that time, a humane outcome for cats abandoned in her yard, tossed at her house by horrible people.”

“In those days, it was a given that if you sent a pet to animal services or any shelter, it was going to die,” says Lynne Scott, the founder of Craig Street Cats, an organization that humanely manages the current population of free-roaming cats in Winnipeg. “She was, in her way, providing what solutions were available to her at that time, a humane outcome for cats abandoned in her yard, tossed at her house by horrible people.”

In 1964, with her cats numbering 20, Rand began openly advocating for a heated clubhouse or a fenced-in area where cats could live, avoid death, and possibly find new owners to take care of them.

“I’m sure,” Rand wrote in her first letter to the editor of the Free Press published since her memorial to Karl Sock, “there would be many kind people like myself to help out and put this noble cause over the top. Seems to me there are oceans of money or grants for underpasses, bridges, roads, or building a new city hall, but not a helping hand to our unfortunate, unwanted animals.”

Inadvertently, Bertha’s call for humanity triggered a series of events that led to her unceasing legal troubles.

Neighbours on all sides formed the Queen Street Committee, convinced — with concerns both legitimate and exaggerated — that the cats needed to go.

For the next two years, the city council of St. James debated at length what to do about “Miss B. Rand and her cats.” Some defenders stepped forward. A St. James resident named Norma Burgess, of 134 Kane Ave., pleaded with councillors to find a middle ground between punishing Rand and extending the plight of her annoyed neighbours. She even provided a solution: free of charge, local contractor Alfred Pastrick agreed to build a fenced-in enclosure with a roof to go up in Rand’s backyard.

“These animals are Bertha’s reason for living,” she said. Alderman J. Frank Johnson called it “the most constructive discussion so far,” but the support from the city never came close to equalling Burgess’s or Pastrick’s, or that of the cat lovers who would drop food in the yard to help where they could.

An inspection by the St. James police, the Humane Society and a veterinary surgeon conducted at Rand’s house in January 1966 found that there were 23 cats in all, each in “satisfactory” condition, with absolutely no evidence of cruelty. The animals were well-fed and healthy.

But it didn’t matter. Soon, the draft for an animal control bylaw was written up. It was never stated directly the bylaw was in response to the cats of Queen Street, because it didn’t need to be said: each resident and each councillor knew as well as Bertha Rand did why No. 10639, and later, No. 10640, were written.

The penalties were fines, which could become jail sentences if they went unpaid. But worse, a successful charge meant homeowners would be prohibited from keeping animals on their land. To Rand, it was a penalty akin to murder.

Facing charges of her cats creating a nuisance in January 1967, Rand and her lawyer won in court, with the judge ruling the bylaw’s application was discriminatory — worded specifically to single Rand out for punishment — as argued convincingly by lawyer Barry Krawchuk. Bylaw No. 10639 was deemed invalid.

“TRIUMPH FOR BERTHA,” the headline read, and in a photograph taken in her kitchen, Rand flashed the photographer a “V” sign for victory.

“I’m very happy about the decision,” Rand told a reporter from the Tribune. “I don’t think my neighbours or city council are. But I don’t care about them. The animals are more a friend to me than they are.”

Then in June 1967, the police came back with a summons and charges under a fresh bylaw. After finally getting better, things got worse.

5. Oh, dear me

“Oh, dear me,” Bertha Rand said.

She was sitting in court, and had just been convicted, sentenced to pay $250 or spend 20 days in jail. Lawyer Barry Krawchuk, after helping Rand evade a similar bylaw not nine months earlier by framing it as discriminatory, had not been able to pull the same trick twice.

His client didn’t have $250, he told the court, and at 73 years old, Rand was headed for the Vaughan Street detention centre and later the women’s jail in Portage la Prairie. The court date and guilty charge were a thinly veiled attempt by the city to get Rand out of her house and remove all cats but three.

But the plan was thwarted: a benevolent stranger paid her fine, freeing her and allowing her to return to her cats, but not getting the police off her back.

The day after Rand’s release from Vaughan, St. James officers arrived at 350 Queen St. Chief Maltby said it was likely Rand would be charged again, and told the Tribune the police would return “as frequently as possible” to check on the number of cats. Daily visits were not ruled out.

The reason for the excessive frequency, Maltby said, was that a police officer could not assume she had more than three cats; he had to be able to testify on a witness stand and say he saw the felines with his own eyes.

It was clear then as ever that the authorities were looking for a way to get rid of Rand, who saw herself as solving problems — overpopulation of strays, the kill shelter system — the city did not seem to worry about.

Someone reportedly offered her an acreage in St. Boniface, and Rand admitted she wanted to get her cats out of the city, but she lived on Queen Street. She bought her house with hard-earned money. She wasn’t interested in giving in to political pressure. Like clockwork, the police arrived at her doorstep to count her cats.

Meanwhile, criticism from her neighbours grew more intense; after years of agitation, Rand grew less and less appreciative of the attention. A fire alarm went off at Rand’s house in October 1967, and a neighbour who responded accused the elderly woman, likely hysterical owing to the situation and the safety of her cats, of slapping her. That led to not just a charge of violating the cat bylaw in St. James magistrate’s court, but of assault at the provincial level.

It was that charge of physical assault, and not of cat ownership, that paved the way for one of the greatest tragedies and indignities of Bertha Rand’s life.

Rand was committed in February 1968 to the Hospital for Mental Diseases in Selkirk, where she stayed for more than one month, leaving her cats and her house on Queen Street. The Crown attorney said indications were she suffered from what was then known as chronic paranoid schizophrenia.

While she was gone, former Humane Society president Ross Murray and a group of other cat lovers took in her pets, nearing 30 in total, promising to protect them until Rand could return. With the help of Laura Watson, a friend of Rand’s who held power of attorney, a trust fund was struck up to support Rand and the cats. Upon her release, Rand said she intended to comply with the bylaw, which had been a thorn in her side for nearly four years.

As it turned out, Murray and others had managed to find caring permanent homes for several of the cats in preparation for Rand’s return to Queen Street. They had also secretly kept 10 cats at a house in Charleswood, where group members took turns taking care of them.

They were kept inside, the yard was kept clean and no neighbours knew they were there, Murray said; in Charleswood, the pet bylaw, enacted in April 1968, said no prosecutions could occur without complaints from neighbours to support them.

Then, on May 8, 1968, fire.

All 10 cats in the house at 526 Berkley Ave. were burned alive. The Charleswood RCMP suspected arson, though the mayor heard the fire started with a spark and a chesterfield. An investigation ruled out arson, with assistant fire commissioner Derry Newton confirming the fire originated in a hot-air floor furnace. Early reports of arson “were probably the result of someone’s vivid imagination.”

Regardless, Rand’s worst fear had come true. Without her nearby to protect them, 10 precious animals were gone.

6. The pet cemetery

To the funeral, Bertha Rand wore a gingham-patterned over coat, a black cloche hat, black gloves and a look of despair.

She was standing in a field about six kilometres east of St. Adolphe, staring down at a large pile of dirt. This was not supposed to happen. The cats were supposed to be safe in Charleswood. But the furnace malfunctioned, the fire started, and now, she was here.

With Frances Campbell, who ran what was then called the Animal and Bird Cemetery, Rand laid down a small bouquet of flowers and thistles atop the soil mound, the corners of her mouth turning downward and inward as she said goodbye. A Tribune photographer was there to document the rite of passage at what was then a relatively empty burial ground. A marker atop the plot read, “Ten Pets, loved and fought for by Bertha Rand. May 10, 1968.”

The cemetery today is fuller, with hundreds of gravestones telling short stories of love and loss. Some are obviously for pets, like the rust-coloured stone for Sam, “beloved poody of Nick & Anne Lubinski,” who died Sept. 14, 1980 at the age of 14; or Thumper, born Jan. 15, 1978, and died Aug. 12, 1984 — “He gave us love,” reads his epitaph; and “Our Pal Muffin,” who lived from 1982 until 1994.

Others seem like they mark the resting place of people, with first and last names that could have belonged to lawyers, nurses, teachers or janitors: Mork Zimmerman, standard poodle; Lutz Beinke, whose grave is protected by a tarped roof; 16-year-old Chico Castagna; Peter Ciastko; and Rufus Boyko.

One pet named Pepper, who died in 1988, is “loved forever” by “mom and dad.”

Rand couldn’t afford a fancy headstone for her cats, so the lettering has since faded away, making it impossible to locate the plot where she stood in 1968.

Seeing the graves of Nikki and Rose-Bud and Boots McCaw, it becomes obvious that to many of the mourning owners, these animals transcended being merely pets. They were family members, and for Rand, they were only the latest ones she had to wish goodbye.

7. The final decade

The last 10 years of her life, Rand fought two battles simultaneously: one against the police and her neighbours, and one against her own mind.

Even after the heartache of 1967 and 1968, the city council and police in St. James kept on about enforcing the bylaw, serving the Queen of Queen Street with a permanent injunction in 1971 and offering her an ultimatum: get rid of the cats, or we will do it for you. She appealed to legal aid, but was told she didn’t qualify. “I don’t know what to do,” she told reporters.

She attempted at first to limit her cats. But people kept coming by and dumping cats on her front lawn, on her doorstep, and in her backyard. Two kittens arrived the same week as the injunction. Rand could not turn them away.

Rather astutely, Rand summed up her predicament to the Tribune, encapsulating the very issues she’d long tried to address of overpopulation and poor ownership. “They can throw the cats out. There’s no law against it. But I can’t keep them.”

She was 76 years old, tired of fighting but seeing no other option as her mind and physical well-being began to truly worsen. She’d been breaking the law for years, yes, but the punishment was unceasing, and as pointed out by many commentators, it verged on the point of absurdity.

”They can throw the cats out. There’s no law against it. But I can’t keep them.”–Bertha Rand

In 1972, Winnipeg city council was asked to uphold the bylaw, with Rand facing charges of contempt of court. Her lawyer, Greg Brodsky, argued the bylaw should be repealed because it was discriminatory. Councillors voted that down. One suggested the bylaw extend across the city and was turned down.

Coun. June Westbury said she felt Rand should be “relocated to a rural area where she won’t have any close neighbours to take offence at her pets.” (The current responsible pet ownership bylaw allows residents to own up to six cats if they have no dogs, but owners can now apply for “excess animal permits.”)

Rand retreated into her home, and turned to an old friend — the radio — to get her voice heard. Several times a week, for years, she would call Peter Warren, the host of CJOB’s popular Action Line show, telling him each time that the city “needed a cat house.”

Warren was an eminent journalist, a legendary figure in broadcast news who once had four escaped convicts give themselves up live on his show. He interviewed Muhammad Ali and 10 Canadian prime ministers in person. Pierre Trudeau once called an interview with Warren something “worse than Question Period.”

But when Rand called, he picked up, becoming one of the only people she communicated with on a regular basis in the last years of her life. She called him every day, but most days he would say “You’re on the air!” and chat with her during commercial breaks.

“She was a legitimately intelligent woman, and she wasn’t crazy. She just loved pussycats, goddamn it,” says Warren, now living in British Columbia. “I think had she just been left alone, she would have been the same lady whom I loved.”

“She was a legitimately intelligent woman, and she wasn’t crazy. She just loved pussycats, goddamn it.”–Peter Warren

As she got older, she called less frequently. From time to time, Warren would stop by to check in on her on Queen Street, having coffee now and again and listening to Rand talk about her cats, her neighbours, whatever she wanted.

Even surrounded by cats, Warren could sense the value she placed on human company.

Rand remained on Queen Street throughout the 1970s, her mental capacity waning and her ability to care for the growing cat collection, which reached 30, disappearing as the decade wore on.

In October 1981, she was taken to Princess Elizabeth Hospital. From her deathbed, she spoke often about her cats. “Once in a while,” head nurse Margaret Sullivan said at the time, “she would call out an animal’s name, as if she was wondering where it was.”

On New Year’s Eve 1981, Rand died at the age of 86. Not only did her obituary run on the front page of the Free Press the following Monday, it ran above the masthead, so nobody could miss it.

8. Return to Queen Street

“Do you know who used to live at this address?” I asked after knocking on the door at 350 Queen St. in April.

“I do,” Cathy Vechina replied. “Do you?”

What’s so great about cats?

Last year, the Winnipeg Humane Society adopted out 2,777 cats, a drop from 3,361 in 2019. We asked people who adopted a feline companion during the pandemic the above question.

Last year, the Winnipeg Humane Society adopted out 2,777 cats, a drop from 3,361 in 2019. We asked people who adopted a feline companion during the pandemic the above question.

“I think one reason people are so obsessed with their cats is that they’re so weird. With a dog, you know exactly what they’re thinking, and it’s obvious they’re motivated by a desire to protect you or play with you. But with cats, it’s kind of like living with an alien. Sometimes they’ll curl up on your lap and purr, other times you try to pet them and they’ll go after your hand like you’re a murderer.

It makes it so much more gratifying when they do decide to love you, like you earned it. It sounds kind of like a toxic relationship when I explain it, and I understand it sounds ridiculous to people who aren’t into cats, but it really is the best.”

— Amelia Williams, Vancouver

“Floyd adjusted beautifully to home, and now it’s so much less depressing to be here all day while one of us is home and the other is at work. My partner and I both struggle with anxiety (and depression in my case) and having Floyd to take care of makes getting out of bed every morning so much easier for both of us. He’s pretty needy and very busy, so we never feel alone in the apartment anymore.”

— Sydney, Winnipeg

“Well, we haven’t seen a mouse since we got Jojo.”

— Monique Woroniak, Winnipeg

“After not having a cat for about 20 years, you lose sight of how much personality per square inch you get with one. They can be playful, moody, mysterious and downright goofy sometimes.

They’re also really gorgeous to look at and photograph — like having a little lion in our house.”

— James Turner, Winnipeg

Being a single guy, no more roommates during this pandemic, it’s just been myself and my cat, Beans, and it has been amazing. It’s given me companionship. It has given me additional responsibility, a living being to look after.

I can tell how much she loves me (despite cats being not known for their affection) and the feeling is mutual. She has definitely made the lonely times up north with no family and just myself in my house, a lot less lonely.

— Josh Goldstein, The Pas

In 1982, Vechina and her husband Carlos, both in their mid-20s, were looking for a place to start their lives together when Rand’s property came to market. Vechina grew up in Pilot Mound and her grandmother was born in 1916 in Crystal City; she knew Bertha Rand before she became Bertha Rand.

The house was at that point decrepit beyond salvage and had been condemned by the city. The lot was available for $10,000. The Vechinas went for a viewing.

To this day Carlos remembers the smell inside the house, which was more like a shack. The floors were caked with cat urine and feces. The backyard was full of discarded lumber and dying branches. There was nothing worth saving. The house and yard were razed, as was the shed in the backyard. Underneath it, a crew found a burial ground for several cats.

They built a new house on the lot, moving in on Halloween night in 1983. Neighbours thanked them for being there, and told them stories about Rand, whose energy loomed over the property long after she was buried in Crystal City, next to her father and mother.

A few years after the Vechinas moved in, Carlos came home from work and saw a six-week-old kitten, without a licence, in the flowerbed, lying between the lilies. “Tomorrow,” he told Cathy, “I’ll go knock on doors and find whose cat this is.”

That never happened. They named her Georgia and she stayed for 14 years. They just couldn’t turn her away.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.