Getting stuck Canadians are largely in favour of vaccination, so why are Manitoba's school immunization programs so far from achieving herd immunity?

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/04/2021 (1684 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Sometimes, neither a lollipop nor a dinosaur sticker is enough to convince someone to get a needle.

Dr. Michele Feierstein, a pediatrician for more than 35 years, knows that all too well.

Feierstein has given thousands of immunizations to young patients throughout her career, but she has also had her fair share of difficult conversations with parents who are vaccine-hesitant or outright anti-vaxxers.

She does not bar families who have lukewarm feelings about or adamant views against immunization, whether they be rooted in misinformation, distrust, religious belief, or any other reason, from her practice at the Manitoba Clinic.

Instead, she answers their questions without judgment, provides them with factual information, and hopes her efforts will convince them to protect their children and others from vaccine-preventable diseases.

“It’s a huge time commitment — huge, huge, huge,” Feierstein said. “It’s more than one visit, you spend a lot of time with these people, and it’s usually people who you have known for several years, who you can change their mind.”

No matter the vaccine-preventable disease, the general principle in public health is that herd immunity is unlikely if immunization uptake is under 80 per cent. The gold standard is between 90 to 95 per cent or above; the more highly infectious a disease, the higher the requirement for immunization and antibodies from prior infection to protect a population.

As the COVID-19 vaccination rollout carries on, addressing vaccine hesitancy — a key stumbling block to achieving herd immunity and ending public health restrictions — is top of mind.

School vaccination rates in Manitoba

The Free Press filed freedom-of-information requests for a breakdown of school-by-school and division-by-division vaccination rates for the grades 6 and 8-9 immunization programs from Shared Health and each of the five health regions, during the 2018-19 school year.

The provincial authority indicated it did not collect such data, while nearly every region indicated it had different data available.

The Free Press filed freedom-of-information requests for a breakdown of school-by-school and division-by-division vaccination rates for the grades 6 and 8-9 immunization programs from Shared Health and each of the five health regions, during the 2018-19 school year.

The provincial authority indicated it did not collect such data, while nearly every region indicated it had different data available.

Winnipeg

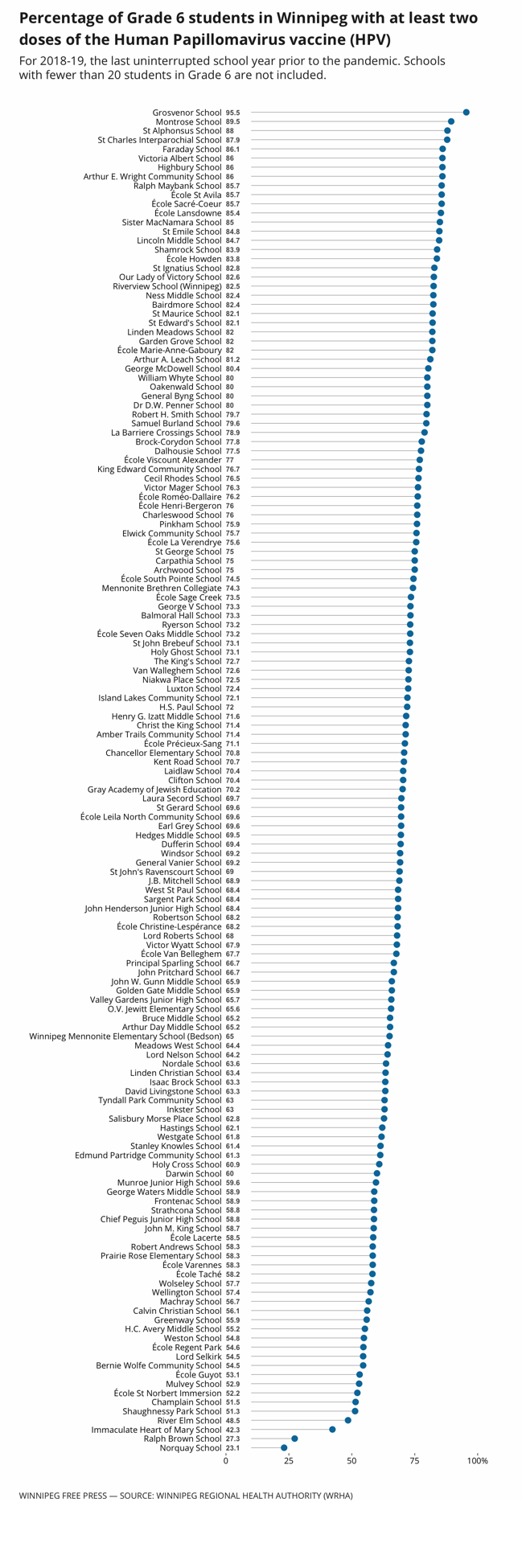

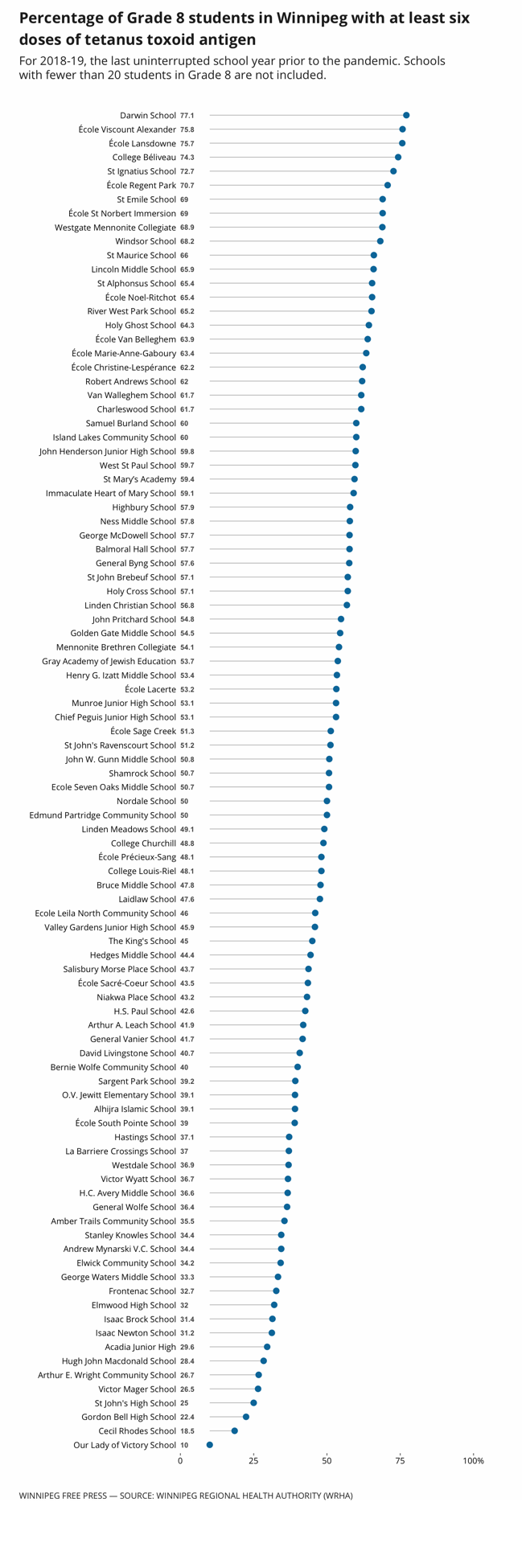

The Winnipeg Regional Health Authority provided school year-end vaccination reports for Grade 6 hepatitis B, Grade 6 humanpapillomavirus and Grade 8 Tetanus shot uptake in 2018-19. (The Tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis vaccine, or Tdap, is typically administered via school programs in Grade 8, but Winnipeg only had figures for overall Tetanus status.)

The Winnipeg data includes school names, total students in each grade who were eligible for a vaccine, and the number of students who are up-to-date with public health’s immunization schedule — which is two doses of both Hep B and HPV shots by the end of Grade 6, and at least six doses of Tetanus toxoid antigen by the end of Grade 8. The reports also include average rates in Winnipeg in all these categories.

Citing confidentiality, the region did not provide information regarding schools where fewer than 20 students were being reported on.

Region averages: Grade 6 Hep B (75.3 per cent); Grade 6 HPV (69 per cent); and Grade 8 students with at least six doses of Tetanus toxoid antigen (47.5 per cent).

Interlake–Eastern

The Interlake–Eastern Regional Health Authority provided school immunization rates for its Grade 6 HepB, Grade 6 HPV and Grade 8 Tdap programs in 2018-19, by individual community area. There are 16 areas, which include Lac du Bonnet and Gimli-area schools, among others. The document also includes health authority-wide average rates for each vaccine category.

Region averages: Grade 6 Hep B (78 per cent); Grade 6 HPV (67 per cent); and Grade 8 Tdap (78 per cent).

Southern and Prairie Mountain

Both Southern Health and Prairie Mountain Health provided the total number of pupils in each relevant grade in 2018-19 in their respective regions, as well as the total number of children who received doses of the relevant vaccines recommended in the provincial immunization schedule that year.

The regions both submitted tables that outline HepB and HPV figures among children born in 2007. Southern’s data included Tdap rates for students born in 2005, as well as 2004, because the program targets both grades 8 and 9 students in the region. Prairie Mountain’s data includes a combination of grade 8 and 9 students in 2018-19, as well as the total pupils in that category who received the vaccine.

Southern averages: Grade 6 Hep B (44 per cent); Grade 6 HPV (45.8 per cent); and Grade 8 Tdap (55.4 per cent).

Prairie Mountain averages: Grade 6 Hep B (59.8 per cent); Grade 6 HPV (65.5 per cent); and Grade 8-9 Tdap (31.8 per cent).

Northern

The Northern Health Region provided school immunization data for programs — including the Grade 6 HepB, Grade 6 HPV and Grade 8 Tdap — in the school districts of Thompson and area in 2018-19.

Thompson-area averages: Grade 6 Hep B (17 per cent); Grade 6 HPV (66 per cent); and Grade 8 Tdap (57 per cent).

Note: In September 2019, Manitoba adjusted its immunization schedule to start to offer the Meningococcal vaccine as part of the Grade 6 school vaccination program.

“There’s the direct protection you get from vaccination… but it’s also part of a social contract that we have with each other,” said Shannon MacDonald, an assistant professor of nursing at the University of Alberta, who studies determinants of vaccine uptake. “For the same reason that we don’t blow through a red light and risk hitting somebody else, we get vaccinated so that somebody else doesn’t get sick.”

Every vaccine is unique, as are the reasons an individual chooses to get or abstain from a shot, but health-care professionals often encounter similar questions and concerns around hesitancy: a grey area in which patients are in limbo about whether to get vaccinated, often because of issues around access and trust.

In an effort to gauge how Manitoba’s longtime immunization programs are doing and pinpoint where rates are both stellar or subpar, the Free Press sought out school-by-school vaccination rates for annual shots offered via school immunization programs.

“(Vaccine coverage numbers are) a fantastic place to start, because that can show us where we might need to be focusing some more attention,” said Julie Bettinger, a professor of pediatrics at the Vaccine Evaluation Center, which is jointly supported by the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute and University of British Columbia.

“If your vaccine coverage is 50 per cent, that’s probably an indication that you need to figure out what’s going on there. It doesn’t mean that the 50 per cent who aren’t vaccinated are all hesitant or that they’re all resisting vaccines, but it does indicate that there’s a problem.”

The vaccine with ‘an image problem’

It was only five years ago that Manitoba expanded its human papillomavirus virus (HPV) vaccination program to include both boys and girls.

Before that, dating back to its inception in 2008, the annual school immunization program aimed at protecting against HPV — a sexually transmitted disease that can cause cancer and genital warts — was offered only to girls.

It was only five years ago that Manitoba expanded its human papillomavirus virus (HPV) vaccination program to include both boys and girls.

Before that, dating back to its inception in 2008, the annual school immunization program aimed at protecting against HPV — a sexually transmitted disease that can cause cancer and genital warts — was offered only to girls.

“(The vaccine) still suffers from sort of an image problem, if you will,” said Dr. Julie Bettinger, who researches vaccine hesitancy and attitudes around immunization uptake at the Vaccine Evaluation Center in British Columbia.

“I don’t think it’s ever very good when you target a vaccine just to one segment of the population, because then that raises all sorts of questions. The other side of it is it’s a vaccine that prevents cancer, but the human papillomavirus is spread through sexual contact so right there, suddenly, it gets quite complicated to talk about.”

The premise behind the initial rollout in Canada was to protect girls from cervical cancer, but the program has been expanded in recognition that anyone can be a carrier of HPV, for which there is no cure.

In fact, an estimated 75 per cent of sexually active Canadians will have at least one HPV infection in their lifetime, according to Health Canada.

In 2018-19, average uptake for both doses of the Gardasil vaccine in Winnipeg was 69 per cent, according to school year-end vaccination reports obtained by the Free Press.

That figure is six per cent less than uptake for both hepatitis B (HepB) shots, which are also part of the annual Grade 6 school vaccination campaigns.

“That’s a sign that people are selectively refusing HPV vaccination,” said Dr. Shannon MacDonald, who researches determinants of vaccine uptake at the University of Alberta.

MacDonald, an assistant professor of nursing, attributes the lingering hesitancy around the vaccine to how it was first rolled out; public health messaging touted Gardasil as a shot to prevent sexually transmitted disease.

“A lot of parents and schools and religious organizations balked at that, ‘Why are we giving Grade (6s) a vaccine against a sexually transmitted disease?’” she said.

A professor of community health sciences at the University of Manitoba, Michelle Driedger said some schools — particularly private and religious-based schools — in Manitoba have been reluctant to even send information home to parents about the vaccine so families can make an informed choice.

A single school in Winnipeg, Al-Hijra Islamic School in River East, had zero per cent uptake for the vaccine in 2018-19.

Norquay School and Ralph Brown School, both elementary schools in the Point Douglas area with significant Indigenous populations, had the second- and third-lowest uptake numbers, at 23.1 per cent and 27.3 per cent, respectively.

Public health officials could do a much better job at promoting the HPV vaccine as one that protects patients against cancer, MacDonald said.

She added, “Yes, it’s a sexually transmitted disease, (but) we’re giving it to your child at the age when we know that a) it works most effectively and b) it’s before even the minority of kids have started sexual activity.”

Owing to parent concerns that their middle schoolers are too young to be vaccinated against HPV, some Manitoba physicians set up alternate vaccination schedules with their patients to administer Gardasil shots later than Grade 6.

Ultimately, Bettinger said debunking myths and misconceptions is key. HPV is still a relatively new vaccine and parents continue to have questions about why it’s needed and how safe it is, said the professor of pediatrics at the University of British Columbia.

“Could we set up a conversation with parents at (low-uptake schools) to help them better understand why it’s still important that their children get this vaccine?” she said. “And understand that it’s actually preventing cancer and will protect their reproductive health rather than harm it?”

— Maggie Macintosh

Should perceptions of public health’s trustworthiness affect uptake of an existing vaccine in one community, it’s unlikely members of that community will have faith in the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines, Bettinger noted.

Every academic year, public health nurses across the province run free school vaccination clinics for students in Grade 6 to receive two doses of both the hepatitis B (hep B) and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines.

The former protects against a disease that attacks the liver and increases risk of organ failure, cancer or cirrhosis, while the latter is to protect against a sexually transmitted disease that can cause cancer and genital warts.

Nurses also offer in-school shots for students in Grade 8 or 9, depending on the district, to get the tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (Tdap) vaccine — protection against bacterial infections and whooping cough.

Students can also get these jabs at a doctor’s office, should they miss the school clinic date or choose to do so for whatever reason.

Following a series of Free Press freedom-of-information requests, Manitoba’s five regional health authorities provided a patchwork of data for these vaccines during the most recent uninterrupted academic year, 2018-19. (In fall 2019, the Meningococcal vaccine was added to the Grade 6 program.)

Aside from the Northern Health Region, which only had data for students in the Thompson area, every authority provided region-wide averages in some form. Overall, the data, which was obtained after months of delays, indicate no health region is achieving even 80 per cent uptake, the lowest end of the herd-immunity spectrum, for any of the doses recommended by Manitoba Public Health in these grades.

The data show Interlake-Eastern has the highest vaccination rates for both hep B and Tdap in the province, with 78 per cent of its student populations fully vaccinated against these diseases. In Winnipeg, 69 per cent of Grade 6 pupils in 2018-19 received the recommended two jabs to prevent HPV.

On the bottom end of the list, Northern reported rates of 17 per cent for hep B, Southern had 45.8 per cent of sixth graders receive their HPV shots, and 31.8 per cent of Grade 8s in Prairie Mountain received the Tdap jab.

“The risk, when vaccination coverage drops, are potential outbreaks of disease,” said MacDonald in a phone call from Edmonton. “If coverage rates drop for pertussis vaccine, we see babies in the ICU on ventilators with whooping cough.”

If vaccination rates drop for hep B and HPV, which are bloodborne or sexually transmitted infections, the impact is seen years later, she said, noting one result is rising numbers of preventable deaths related to cervical cancer.

Only the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority provided a breakdown of schools, except for those with fewer than 20 eligible pupils in the respective grades, and the percentage that was up-to-date with Manitoba’s immunization schedule. Other regions indicated they did not have such specific data.

The average rates for uptake of two shots of both hep B and HPV, offered during annual school clinics at the 148 Winnipeg schools, is 75 per cent and 69 per cent, respectively. Immunization rates for tetanus boosters among Grade 8 students is even lower, with less than half of the student population in Winnipeg adequately immunized against the infection.

The Winnipeg health authority declined multiple requests to contextualize the data and provide information on vaccination strategies. Manitoba Public Health also declined interview requests, offering instead generic statements about how vaccines are recorded — data from health regions about school programs and individual doctor’s information ends up in a massive information management system — and monitored.

The province relies on annual reports that document immunization surveillance and communicable diseases, as well as a provincial immunization registry, in planning vaccination strategies, according to a provincial spokesperson. The most recent reports posted are from 2017.

However, there are no provincial-specific targets for hep B, HPV and Tdap in Manitoba.

“Data isn’t information and information isn’t knowledge and knowledge isn’t wisdom. We need data, information, knowledge and wisdom in order to promote public health,” said Arthur Schafer, a philosophy professor with expertise in bioethics at the University of Manitoba.

Schafer said that publishing data without any analysis, nor a plan to improve rates in areas with dismal uptake, is hardly useful.

He added that he’s surprised at how little public discussion there has been around the health consequences of differential vaccine uptake in Manitoba, what public health officials know about it, and what, if anything, is being done about it.

The variance in what regions collect and absence of consistent data on immunization rates across Canada is “hugely problematic,” said Michelle Driedger, a professor of community health sciences at the U of M.

“Our data is terrible… We do need to have better centralized reporting. We need to have some consistency. There needs to be some kind of consensus agreement, provincially, federally and territorially, about what we are going to focus on in collecting,” said Driedger, who researches health-risk communication and vaccine hesitancy.

Inconsistent data does little to promote confidence in a system charged with the responsibility of public health, she said.

The WRHA data that is available suggests intervention is needed to determine why rates are consistently low, no matter the vaccine, in Transcona, Point Douglas, Inkster and River East — Winnipeg neighbourhoods that ranked among the bottom in uptake for both Grade 6 and 8 school programs in 2018-19.

Norquay School and Ralph Brown School in the Point Douglas area were among the bottom three schools with the lowest rates for hep B (30.8 per cent and 39.4 per cent, respectively); and HPV (23.1 per cent, and 27.3 per cent, respectively).

As for the percentage of students with up-to-date tetanus shots, Our Lady of Victory School in Riverview, and Inkster-area schools Cecil Rhodes School and Shaughnessy Park had rates under 20 per cent.

“The numbers are so low. I can’t believe it. If that’s truly the school immunization program and it’s being recorded and reported properly, it’s a failure. We’re not getting herd immunity for a lot of our immunizations,” said Feierstein.

Only six per cent of the 148 schools included in the data met the 90 per cent threshold for two doses of the hep B vaccine, while an elementary school in Crescentwood was the only one that also achieved it for the HPV vaccine.

It’s a mystery to both Grosvenor School administration and the parent association as to why the school achieved such high buy-in.

There are numerous factors that could be at play when it comes to uptake, be it high or low. For school programs, absenteeism, student anxiety and needle phobia, misplaced consent forms, and language or literacy barriers can affect whether or not a student gets a jab. Newcomer student files might also exclude immunizations received prior to moving to Manitoba.

“It’s really discouraging to hear those numbers,” said Radean Carter, spokeswoman for the Winnipeg School Division, reflecting on division schools recording some of the lowest rates in the city. “It sounds like we need to do even more work with our intercultural and community support workers to help increase those numbers.”

The translation of consent forms is an easy fix in comparison to addressing systemic distrust and other deep-rooted factors that cause hesitancy.

Feierstein said there needs to be a re-think about how vaccinations are provided in many areas in the city, given the school vaccination data, which indicates many schools with low rates are in communities with poverty and notable racialized populations.

“If we agree that there’s vaccine hesitancy, the only way you’re going to get more people immunized is to make it the easiest thing possible,” the pediatrician said. “If you make it difficult, they have 600 reasons why they’re not going to go get their vaccine.”

Amid the COVID-19 vaccination rollout, the team at Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre, which provides the urban Indigenous population in Winnipeg with community-based programs and services, has been conducting surveys about vaccination.

Executive director Diane Redsky said fear of both the unknown and the health-care system in general have been common themes of hesitation in the inner city, North End and Elmwood. “For Indigenous people, (hesitancy stems from) a combination of access and the relationship we have with the public health system. It has not always been favourable. There’s some mistrust, and some of that is very true with experiences of systemic racism,” said Redsky, who is Ojibwe from Shoal Lake 40 First Nation.

Those reasons might contribute to the low rates in schools with high Indigenous populations in the inner city, including Norquay and Ralph Brown.

Ma Mawi is running a COVID-19 vaccination centre, in part to address some of these concerns; staff will also do door-to-door outreach in the North End to let residents know about the trusted community-organization-run centre.

“This (pandemic) will be a learning experience, I believe, for the province, in how to prioritize vulnerable populations,” said Redsky.

In the opposite end of the city, in Dr. Ruth Grimes’ practice in southwest Winnipeg, students who are not up-to-date with their immunizations tend to come from either wealthy families or families from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

“The outcome is the same, but the underlying trigger is very different,” said Grimes, a community primary care and consultative pediatrician.

Whereas parents who are trying to make ends meet may not prioritize immunizations because of urgent concerns relevant to daily living, such as food insecurity, higher income caregivers may have more time to do research and question the pharmaceutical industry.

Researchers have found hesitancy is frequently associated with highly educated parents who actively seek out information.

It is often easier to find false information about vaccinations online than it is to find facts, said Driedger, who studies health risk communications.

Anti-vaxxer campaigns package bogus science in a way that appears to be very convincing, she said, noting the myth that vaccinations cause autism — which has been repeatedly debunked by legitimate science — has resonated with parents.

Misinformation aside, Driedger listed cultural and religious beliefs, as well as traditional conservative ideals that favour individual choice rather than government interference, as other factors that affect hesitancy and outright rejection.

“Even though doing nothing is still a decision, sometimes parents will feel more comfortable in making a decision not to immunize their child, even though their child might get exposure to that disease and maybe they catch it and maybe they even develop serious consequences and they might even die,” she said.

“But in their minds, it’s like, ‘That was fate’ or ‘That was God’s will’ — there’s other ways of rationalizing.”

Some of these factors could be playing into Southern Health’s statistics trailing behind other regions, overall, she said, adding that Southern — home to Manitoba’s so-called Bible Belt — traditionally has lower rates than other areas.

“The vast majority of people are not opposed to vaccination; the latest numbers in Canada (are) that between two and five per cent of people would say, ‘I’m not getting my kids vaccines because I don’t believe in them or they’re not safe,’” said MacDonald, of the University of Alberta.

Meantime, she said approximately 20 to 25 per cent of Canadian parents start vaccinating their children, but are behind on immunizations or miss doses. In order to bridge the gap, she prescribes better awareness about immunization schedules, and quality data collection and information-sharing between health-care providers.

In particular, Tdap immunization rates across the province suggest families are not as aware of the shot as they should be, or that tetanus boosters are required every 10 years, said Grimes, incoming president of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

The Winnipeg pediatrician added, “When you don’t see and hear of these illnesses, it comes out of the family’s consciousness.”

If distrust is affecting immunization, recruiting well-known leaders in a community to promote facts about vaccination is one strategy to improve immunization rates.

Adjusting communication strategies, tailoring messaging to unique vaccines, and ramping up reminders could address low rates in areas where accurate information is not making it into parents’ hands. As for problems around access and transportation, setting up mobile clinics or programs in community hubs could go a long way in improving rates.

The first step, however, is determining what’s behind the numbers.

A bioethics researcher, Schafer wants to know if health officials have actually conducted surveys or knocked on doors in communities with low figures to find out what’s behind them.

From his perspective, public health has an obligation to investigate rates, undertake empirical research to find out why they are so low in particular areas, and then take appropriate remedial actions.

Manitoba undertook a childhood immunization mapping project between April 2017 and March 2020 to look into coverage for measles, pertussis, HPV and rotavirus at select ages by geographic district in the five health regions, according to a provincial spokesperson.

The spokesperson said the maps and coverage results were then shared with health-care providers and regional health authority stakeholders to identify causes of low immunization rates.

“By shifting the discussion to local district level, local intervention strategies could be developed, tailored and implemented, as opposed to ‘one size fits all’ solutions at the regional health authority or provincial level,” the spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement.

The results and whether officials will work directly with schools to boost rates remains to be seen.

Ideally, officials should work with community members to identify problems, as well as solutions that are meaningful to them, said Bettinger, who researches vaccine hesitancy and attitudes around uptake.

However, she said it’s unlikely any real progress can be made if public health continues to be underfunded and pressured to roll out vaccines at the lowest cost.

One way primary-care providers can pitch-in is to use every meeting with a patient — be it during a routine check-up or urgent hospital visit — as an opportunity to address vaccination status, said Grimes.

Doctors Manitoba recently launched the “Ask a Doctor” campaign to promote accurate information about the COVID-19 vaccines.

The expansion of such a site to include information about other vaccines could be of great use to physicians who are trying to convince patients to get a shot, said Driedger.

The U of M academic’s recent study on the immunization experiences of newcomers suggests strong recommendations about vaccination from trusted physicians are also critical.

In late 2019, Driedger interviewed Nigerian mothers who had recently immigrated to Winnipeg about their attitudes towards immunization. One common theme she found among respondents was that, although these women were very vaccine-accepting, they reported that Manitoba doctors’ “wishy-washy” language about vaccines was off-putting.

By contrast, they indicated they received thorough breakdowns from health-care professionals in Nigeria, who outlined each disease-preventable vaccine and possible side effects, as well as each disease and all of the risk factors associated with it during appointments.

“There was always a complete sense of what they were getting into, but there was still always that really strong recommendation,” she said, adding that in Winnipeg, these women felt vaccination was posed more as a choice.

“It’s either important or it isn’t, so you shouldn’t be wishy-washy about it… That was their perspective.”

While Health Canada has approved the use of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for people who are age 16 and older, Manitoba has yet to announce plans to immunize anyone younger than 18 against the novel coronavirus.

It also remains unclear when and if the province will take into consideration the National Advisory Committee on Immunization’s recommendation that youth who are high risk and between the ages of 12 and 15 should be eligible for Pfizer shots.

But in Grimes’ sterile office at the Sterling Lyon Health Centre, she has already started to gauge patient feelings about the new vaccines.

“It is coming, and so in appropriate age groups, I will start planting the seed, and I would have to say that most parents are actually on board with the idea, in my practice and in my world,” she said. “It certainly has been heartening to me.”

Despite all the lives lost and on hold during the pandemic, Grimes recently had a conversation with a parent who was resolute in their decision their child would not receive a vaccine.

“I don’t think there’s any way of understanding where that (anti-vaxxer) mindset comes from; it’s like faith, people can’t understand it, but others are immovable by it,” she said.

One challenge leading to hesitancy is the newness of COVID-19 vaccines, but Grimes said what is known about the severity of infection is invaluable in promoting them.

Also concerning for her is fears about the virus, which are preventing families from booking or attending doctor’s appointments and getting caught up on immunizations.

Education disruptions have also interfered with the annual school-based vaccination programs.

Given so many children are getting behind on their immunizations because of the pandemic, vaccine-preventable outbreaks are a real possibility, said Amila Heendeniya, an infectious disease physician at the U of M.

“I bet you anything we will see more HPV-related outbreaks in the future, because of this pandemic wave,” Heendeniya said.

“Unfortunately, it’ll affect the demographic that’s already facing low health care, who don’t have the time to take time out of their day to chase down doctors and chase down vaccines.”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, May 1, 2021 10:55 AM CDT: Corrects typo in quote from Michelle Driedger about cultural/religious vaccine hesitancy.

Updated on Saturday, May 1, 2021 11:11 AM CDT: Corrects grammatical errors.

Updated on Saturday, May 1, 2021 11:37 AM CDT: Corrects further grammatical errors.