The game, the shame In the aftermath of the Graham James sex-abuse horror story, sports officials have long promised changes — but observers wonder where they are

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/12/2020 (1820 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

To ensure Graham James would survive his stay in prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach would sometimes be required to move from one facility to the next.

Serial sexual abusers are never popular behind prison walls. But because of the high public profile of some of his victims, including NHLers Theoren Fleury and Sheldon Kennedy, there were many on the inside who were motivated to deliver vigilante justice.

About this series

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

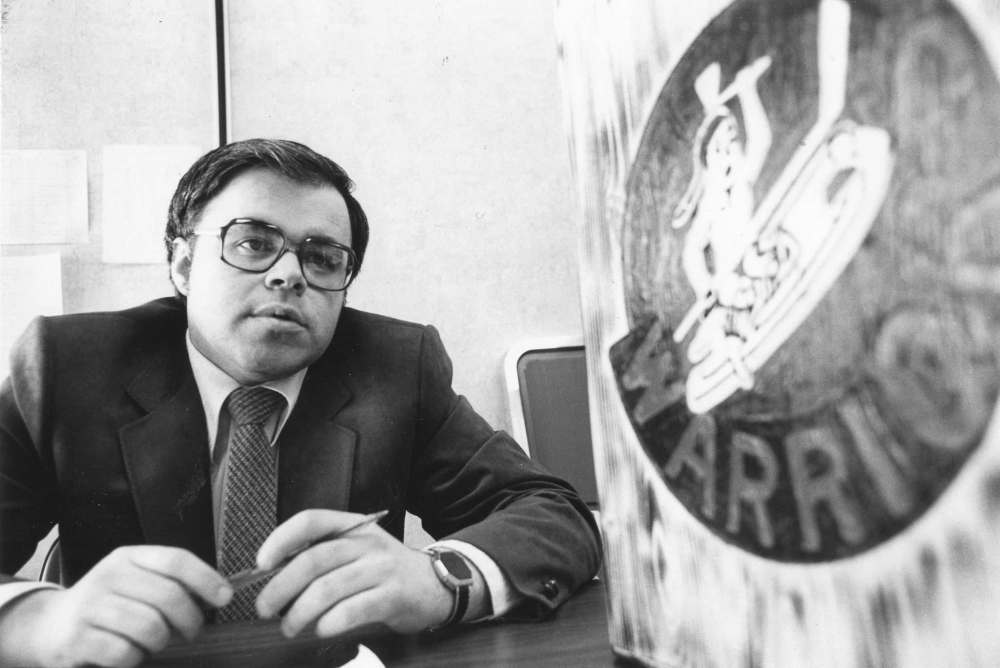

While a significant number of the assaults occurred in Saskatchewan, where he coached both the Western Hockey League’s Moose Jaw Warriors and Swift Current Broncos, the James scandal has always been a Winnipeg story.

James worked his way up through the ranks here — in Winnipeg minor hockey, the Manitoba Junior Hockey League and the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors.

It was with this backdrop that Free Press sports writer Jeff Hamilton began investigating James’ past, from his formative years growing up as an Air Force brat in St. James to his time as a substitute teacher in the St. James-Assiniboia School Division, and from his first foray into coaching minor hockey to his ultimate downfall.

Hamilton interviewed dozens of former players, childhood friends, educators and hockey colleagues and officials.

His investigation reveals an awkward teen who found confidence both in the classroom and at the rink, one that enabled him to embark on his trail of destructive criminal behaviour.

The investigation also paints a picture of complicity or, at the very least, wilful ignorance through all levels of the sport, which allowed James to abuse young players for years.

In total, James has been convicted of sexually assaulting five former players: Sheldon Kennedy, Theoren Fleury and Todd Holt have all publicly shared their ordeals; the identities of two others have been protected by publication bans.

However, police estimate the true number of victims is between 25 and 100.

While powerful institutions, such as the Catholic Church, and prominent individuals, including Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, have all had their moments of reckoning, there has been no equivalent to the #MeToo movement in hockey.

This Free Press investigation attempts to change that narrative by giving voice to victims and asking questions of those who knew or ought to have known what was happening on their watch.

Read the full six-part series, titled A Stain on Our Game.

Don Cherry, the bombastic frontman for the now-ended Coach’s Corner feature on Hockey Night in Canada, set the tone early. In 1997, shortly after James was sentenced to 3 1/2 years in prison for abusing Kennedy and another unnamed player with the Western Hockey League’s Swift Current Broncos, Cherry used his popular Saturday-night platform to declare the predatory coach should be “drawn and quartered” for what he did.

Shortly after, James contacted the Calgary Sun to say Cherry’s comments had put his life in danger. He complained that he was now living in fear and lamented, ironically, how Cherry could get away with such irresponsible behaviour.

Years later, and not long before James was granted full parole in September 2016, he was transferred to a different facility. Word inside had already spread that James would be joining the population when he first surfaced to take his spot in the meal line.

James looked old and frail, weighing no more than 150 pounds — no longer the out-of-shape coach known for his large pot-belly.

As he inched his way down the line, a soft noise started to fill the room, eventually reaching a pitch for all to hear. The inmates had combined their efforts to intimidate James, humming in unison the iconic theme song to Hockey Night in Canada.

James just stood there, according to someone who witnessed the scene first-hand, with a look on his face that made it clear he was in trouble. At the same prison, inmates covered the window of his cell door with spit, to the point where guards were unable to see through and would have to get James to clean it off.

Though James is now a shell of his former self, no longer in possession of the power and influence he once wielded to manipulate and sexually assault his victims, the reality is he’s just one of many predators that have infiltrated hockey over time and contributed to a toxic culture around the game — a problem that persists to this day.

Part 6 of a Free Press investigation examines the culture of abuse in hockey — and the broader sports scene — and asks the question: are players safer today?

●●●

Just before James’ crimes were made public, Laura Robinson set off on a journey across Canada in the early 1990s. Her goal to was pull back the curtain on a junior hockey culture that she knew was rife with abuse.

In her book Crossing the Line: Violence and Sexual Assault in Canada’s National Sport, Robinson documents one story after another, detailing heartbreaking anecdotes of the abuse of power and exposing the institutionalized violence in hockey and the carnage it leaves in its wake.

Based on numerous interviews, some of which were conducted with sexual assault victims, the book includes stories of multiple gang rapes — which, in one instance, involved a mentally challenged girl in Swift Current while James was running the Broncos — and the cavalier attitudes of players who see women as objects that exist to feed their sexual urges.

It also examined how the adult men and women responsible for providing a safe environment for the teams and surrounding communities were complicit in enabling a culture that allowed teenage boys to run wild with few, if any, consequences.

Robinson says her publisher, McClelland & Stewart Inc., didn’t grasp the brutal picture of Canada’s game and expected the book to focus on James, who had been accused of hundreds of sexual assaults on players.

“I think they thought this was going to be a book about a homosexual man who wandered into hockey and fooled everyone,” Robinson says over a lengthy phone interview from her home in Ontario. “As opposed to an entire culture that says the sexual abuse and rape of children is just fine with us.”

If you wondered about hockey’s influence and power at the time, Robinson offers this nugget: “All the names of important hockey people at the time were removed by the publisher.”

Robinson recalls meeting with James — then considered one of the WHL’s premier coaches — in Swift Current.

”Graham was willing to talk to me in very graphic language about what was going on with all these NHL players.”

“I went in January 1993, to find out about this gang rape, and Graham met me after the game and he said — and he knew I was a journalist — he said, ‘You know, all the NHL players I know, they’ve got a whole list of girls that will f–k them after the game, no matter what town they’re in. It doesn’t matter what city they’re in, there are so many girls who want to f–k them,'” Robinson says.

“And I thought, ‘I can’t believe you’re saying this to a journalist, like, do you think I’m not writing this down?’ (It) struck me that Graham was willing to talk to me in very graphic language about what was going on with all these NHL players.”

After her sit-down with James, she met with a group of excited volunteer boosters for the Broncos —known as the Hockey Hounds — at the local mall. Robinson took a moment to reflect on their unwavering loyalty, asking herself: “Didn’t they know that these guys raped a learning-disabled girl with the intellectual capacity of a 12 year old?”

While Robinson’s work helped shed light on the abuse occurring in Canadian hockey communities from coast to coast, it did little to curb the problem. She was resisted by top officials in the Canadian Hockey League (the umbrella league consisting of the Western, Ontario and Quebec Major Junior hockey leagues), all of whom claimed the sport wasn’t as bad as she was suggesting.

“The problem still hasn’t ended,” she says. “And the thing about sexual abuse is the effects last a lifetime.”

”The problem still hasn’t ended… And the thing about sexual abuse is the effects last a lifetime.”

Earlier this month, more than a dozen former Canadian Hockey League players filed affidavits with the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. The affidavits, which detail numerous disgusting incidents of abuse, many of which were sexual in nature and part of team hazing rituals, are key evidence in a class-action lawsuit filed in June by former players Daniel Carcillo and Garrett Taylor.

• Read the affidavits (PDF file, 600 pages, 6.5 MB)

Listed as defendants in the case is the CHL, along with its three member organizations — the WHL, OHL and QMJHL — and the 60 junior teams that make up those leagues. The plaintiffs claim the CHL and its teams, as well as their respective executives, “have perpetuated a toxic environment which condones violent, discriminatory, racist, sexualized, and homophobic conduct, including physical and sexual assault, on the underage players that they are obliged to protect.”

The affidavits filed by the former CHL players cover a 35-year period, between 1979 and 2014. While each disturbing incident is enough to turn an unsuspecting stomach, there are some that stand out above the rest.

Among them is the sworn testimony of a former player with the then-Winnipeg Warriors.

The player says he was enthusiastically recruited in the 1980s by James, who convinced him to give up his plan of playing U.S. college hockey and accept a trade from the Medicine Hat Tigers, who owned his WHL rights, and join the Warriors for the 1983-84 campaign.

After living in a hotel for a few days, he says James drove him to Edmond Oliverio’s house, telling him how lucky he was to be billeted with such a great person.

Oliverio, a gay man, lived alone in a large house in St. James. Almost immediately after the player arrived, Oliverio encouraged him to drink copious amounts of alcohol and took him out to restaurants and bars. Following one night of heavy drinking, the player said he woke up with Oliverio having snuck into his bed.

“I freaked out. I yelled at him, pushed him and threatened him with violence if he ever did anything like that again,” the player wrote. “I started sleeping with a dresser in front of my bedroom door.”

The sexual advances persisted.

The player says he complained multiple times to Tom Thompson, the team’s general manager, and each time he expressed his concerns he had his position with the team threatened. Thompson denies the claim.

The player added: “I was petrified of the veteran players while I was at the rink, but when I went home, it was even worse.”

”I was petrified of the veteran players while I was at the rink, but when I went home, it was even worse.”

He also detailed the horrors of being assaulted by veteran teammates during various hockey hazing initiations.

It included having his penis tied to a rope swung over a bar suspended above him and attached to a bucket for players to throw pucks in. By the time the torture was over, the player says more than 20 pucks had been tossed in the bucket.

“What was being done to my penis did not even look real,” the player said.

He then had his pubic hair shaved with a dull razor, with the ensuing wounds covered in heat ointment. Not done there, the player says his veteran teammates penetrated his anus with a hockey stick, also covered in heat ointment, so the burning could be felt inside him.

Following the assaults, the player says he retreated to the shower, where he was shaking uncontrollably, trying to understand what had just unfolded. He says James and the team’s trainer consoled him shortly after.

The assaults weren’t limited to the arena. All WHL teams are forced to ride the bus, often driving long hours through the night to play the next opponent. It also provided another opportunity to abuse rookie players.

“They would make us strip naked and spend hours in the bus bathroom, sometimes up to eight at a time, with the lights off so it was pitch-black. They called it the ‘hot box,'” the player wrote.

“Our clothes were tied together into a large knot. The last player to get their clothes on would have to remain in the hot box for the remainder of the trip.”

The player added: “The coaches and team staff were aware of this ritual.”

”The coaches and team staff were aware of this ritual.”

A former Warriors player cringes when told of his old teammate’s statement. He remembers the player fondly.

He says because he joined the Warriors partway through the season he missed the time frame for when veteran players usually initiate the rookies with the kinds of abuse his teammate detailed. The player, who asked to remain anonymous, isn’t surprised it happened; he witnessed the same behaviour first-hand years before, while playing in the Manitoba Junior Hockey League.

As for the antics that took place on the team bus, he says he was present but purposely distanced himself from the abusive behaviour, always taking a seat near the front.

He says anyone on the bus — which would have included head coach Bruce Southern, James, equipment manager Craig Heisinger and Thompson — would have seen what was happening.

Heisinger, currently the assistant general manager and director of hockey operations for the Winnipeg Jets, denied an interview request through the NHL club. Southern, who later was hired by Heisinger to scout for the Manitoba Moose, denied knowledge of the allegations when contacted by the Free Press.

When read the entirety of the player’s claim, Thompson said he was sorry for the player but that he had no idea that was going on.

Thompson, who had a long NHL career in various roles, denied any hazing occurred with the Warriors, though he admits he hardly spent time in the locker room. He says Southern and Heisinger — “the two guys that ran the room” — were not the type of people to condone such behaviour.

The player, who says he was once considered a top-100 prospect, was out of hockey the following year and continues to struggle because of his time with the Warriors.

Other incidents documented in the affidavits include: players being forced to have sex with prostitutes; how rookies were lined up naked and ridiculed for the size of their penises; how other rookies were forced to masturbate on a piece of bread, with the last player to “finish” having to eat it; and, in what is a practice called “mashing,” older players would place chocolate pudding between their buttocks, then lower themselves onto the rookies’ faces so they could eat the pudding off the veterans’ anuses.

In the wake of these traumatic events, players became addicted to drugs and alcohol and struggled with self-esteem issues and intimate relationships.

The CHL issued a statement to the Free Press stating it has taken notable steps to end hazing and that the league takes such “deeply disturbing” allegations very seriously. Part of the league’s efforts include putting together an independent panel chaired by former New Brunswick premier Camille Thériault, with former NHLer Sheldon Kennedy acting as an adviser.

The panel was asked to help the CHL better understand hazing and sexual violence and come up with recommendations to end the haunting rituals.

The Free Press has learned the report has been completed and is in possession of the CHL, and there is a plan to adopt changes to league policies in the new year.

“Most of the allegations are historic in nature and we believe are not indicative of the experiences of current CHL players,” the statement reads.

”Most of the allegations are historic in nature and we believe are not indicative of the experiences of current CHL players.”

James Sayce, a partner with Koskie Minksy LLP in Toronto, and one of the lawyers representing Carcillo and Taylor, says he believes the affidavits can be litigated together but cautioned that it can take time. He hopes a motion will be heard sometime 2021.

“What we see with survivors of sexual assault and sexual abuse is they don’t come forward immediately,” says Sayce. “We’ve alleged a serious culture of silence in the CHL and, so, whether or not it’s happening right now will be a matter for the courts to determine.

“But for the CHL to suggest that this is something that only lives in the ’80s, ’90s, 2000s, I think is, well, we’re going to have to prove otherwise. It’s going to require the scrutiny of a court and a judge and I’m happy to address that defence when the time comes.”

●●●

What bothers Jay Johnson most about hazing rituals, beyond the violence and pain it inflicts on the people forced to endure it, is that it achieves the opposite of what it’s supposed to do.

Johnson, a University of Manitoba professor, has studied hazing and its effects on teams and athletes for the past 25 years. He says while team-building is often viewed as the goal of these initiations, they often lead to a breakdown in trust and, in most serious cases, long-lasting damage to victims.

What Johnson says needs to happen in hockey, as well as other sports and areas where hazing is prominent, is a complete ban of the disgusting tradition. If this kind of abuse is going stop, teams and athletes need to better understand the damage they are doing to each other.

“It’s a cycle, right? It’s all about membership and wanting to be accepted by that group, that hockey team, and this is what they’re requiring us to do to get that respect and get that recognition,” Johnson says.

“So you rationalize it in whatever way you can in your mind at the time and for as long as you are a team. And then it’s further entrenched, because you then become the one doing that to someone else. That completes the cycle — the cycle of hazing, a cycle of violence.”

Johnson says it’s no secret there’s a culture ingrained in hockey for players to be tough, be able to endure extreme pain and resist showing vulnerability or perceived signs of weakness. He says people might read some of the traumatic stories, such as those in the CHL lawsuit, and wonder how players would put up with such heinous assaults.

But it can often be even worse for those who have the courage to push back.

“Resist in any way, (and) more often than not, that player ends up being ostracized and marginalized and probably even ends up leaving the team,” he says. “All because they wouldn’t do what the team was requiring them to do.”

”Resist in any way, (and) more often than not, that player ends up being ostracized and marginalized and probably even ends up leaving the team.”

It’s that with-us-or-against-us attitude, one that still exists today, Johnson says, that can lead to a wall of silence within teams, shielding the public from what really goes on behind closed doors. And while teams in all sports understand the damage hazing can do to their athletes — and the heavy costs associated with civil lawsuits — meaningful action often isn’t taken until a serious problem occurs or a reputation is at stake.

Simply put, he argues, sports should invest in alternative team-building exercises now or pay for it, quite literally, later.

Johnson filed an expert report on hazing, initiations and rites of passages that is being used by the lawyers representing the former CHL players in their pending class-action lawsuit. Through his research he has seen the issues in hockey and other sports first-hand, and argues the stakes have never been higher for instituting meaningful change.

Coupled with the current pause in play owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s no better time than the present, he says.

“There’s a real potential for change here with everything being shut down or at least upended the way it has been in the world of sport,” he says. “A lot of these things, who knows if they come back? Or, I should say, who knows what they come back like?”

●●●

Gretchen Kerr has spent most of her professional life studying the maltreatment of athletes and advocating for safer avenues to report abuse within sport.

The University of Toronto professor figured that after all the recent high-profile sexual abuse scandals in sports, both in Canada and the U.S., she would have already achieved her goal in establishing a national independent body to report and handle allegations. But here she is, years later, still fighting the fight.

And while others might see the sports world inching closer to a reckoning when it comes to acknowledging decades of abuse, Kerr believes there is still too much evidence to the contrary.

A lack of a full accounting of the Graham James scandal is one example. Another is the initial coverup and then the abject failure to properly investigate and protect hundreds of girls and young women victimized by Larry Nassar, a sports doctor at Michigan State University and with USA Gymnastics.

That’s why it’s critical to have an independent oversight.

“(The Nassar fallout) certainly was a case that has scared people in the Canadian context,” Kerr says in a phone interview from Toronto. “Hopefully they’re not waiting for the same kind of fallout. I think we’ve already arrived there.”

Nassar was accused of assaulting at least 265 young women and girls dating back to 1992. His victims included numerous Olympic and U.S. women’s national team gymnasts. In 2018, he was sentenced to decades behind bars, a sentence that ensures he will die in prison.

A 2019 CBC investigation into sexual abuse in amateur sport revealed just how bad things can be. Over the last 20 years, they found at least 222 coaches who have been convicted of sexual offences involving more than 600 victims, all of whom were under the age of 18. Another 34 coaches had cases still pending before the courts.

A total of 36 sports were identified to have a convicted abuser, including hockey, soccer, basketball, baseball and swimming, sailing, rugby, fencing and archery.

Hockey led the way with 86 people charged, 59 convicted and eight still awaiting trial.

Charges were wide-ranging, including sexual assault, sexual exploitation, child-luring and making or possessing child pornography. All persons were charged between 1998 and 2018, though some of the offences may have predated that timeline.

Sandra Kirby, an Olympic rower and University of Winnipeg sociology professor, says that while the number of people who have faced criminal punishment will shock some, it’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“We know sexual abuse is extremely under-reported and that the numbers are much higher,” she says. “But even with everything we know today, everything we’ve learned about sexual violence in sport, there are people who still don’t get it or aren’t willing to understand the magnitude of the problem.”

Kirby says that no sport is immune to predators and that offenders aren’t limited to the coaching ranks; they also include anyone who has access to the athletes. She says she’s not trying to create an environment of fear, but simply wants people to know the issues are real and to recognize the importance of having safeguards in place.

Taking time to confront the sometimes brutal reality of abuse in sport is of paramount importance and will lead to people being better equipped to create a more positive experience for athletes and their families, she says.

“Parents in sport should want this information to be put out there, but more importantly, transparency should include sports organizations providing all available information on coaches, whether they have been criminally convicted or reprimanded or suspended,” she says.

“Parents deserve to know who their child is being coached by.”

”Parents deserve to know who their child is being coached by.”

Kerr says athletes are hesitant to report abuse out of fear that it could affect their status or position within their sport. It can be daunting to reveal details of abuse and extremely uncomfortable to make accusations to high-ranking officials in the same organization.

She says she doesn’t understand why sports organizations are unwilling to cede control over the investigation of abuse allegations. Not only does that send the wrong message; it also misses the opportunity to send the right one, she argues.

By allowing for arm’s-length investigations to take place, sports organizations would be sending a message to families they are taking the issue seriously and that their children will be in a safe environment.

“The big challenge is many of the big sport organizations are resisting this independent body and I can’t understand why it just hasn’t been pulled away from them,” Kerr says.

“You would think that the transparency around this would be a good business decision. But they very much want to hang onto their autonomy and their control in these types of decisions.”

Hockey Canada has resisted giving up power and control over investigations into abuse within its ranks. It’s not the only one, but given its influence in the country, the reluctance is disappointing, Kerr says. The most frustrating part is that if hockey was to jump on board it would benefit all sports organizations.

”We sure don’t want a hockey player in Montreal being treated differently than a squash player in Brandon for the same infraction.”

“We need sports like hockey to step up and that’s because they are so big and prominent that they’ve got resources. It’s a lot easier for them to hire lawyers when cases come up, to hire independent investigators or a hearing panel of members, and things like that,” she says.

“But you take a small sport, where you might have one employee and the rest are all volunteers, they just don’t have the capacity to deal with these cases. And so, having the big sports on side actually helps to provide more resources for all the other sports. It’s a far more equitable situation with that kind of approach, and we sure don’t want a hockey player in Montreal being treated differently than a squash player in Brandon for the same infraction.

“So, I think for the athletes, it’s really important to have equitable access to these complaint mechanisms and to support and to expect the same kind of process that is not based on what sport you are in or where you reside in the country.”

While Kerr remains committed to establishing arm’s-length investigations, she worries that despite the recent attention abuse in sport has been receiving, it will lose momentum, much like it did after the James scandal first broke.

”I’m afraid we’re just going to regress until the next crisis comes along. I hope I’m wrong, but I worry about that.”

“There was tremendous upheaval when Sheldon Kennedy came forward and Sport Canada allocated a lot of money to dealing with abuse. They came out with a new policy that said every federally funded sport organization had to have a publicly accessible harassment policy and two trained harassment officers and they had to be accountable for this on an annual basis. So, it was very similar to where we’re at now in some way, but then the attention fades away and things regress until the next crisis comes along,” she says.

“My fear is that we’re going to repeat where we in the mid, late 1990s, where everybody is sort of in crisis mode now trying to figure out what to do. But when things settle down, and especially with COVID-19 and attention shifting elsewhere, I’m afraid we’re just going to regress until the next crisis comes along. I hope I’m wrong, but I worry about that.”

●●●

In the stuffy world of hockey politics and boardrooms, Mike Bruni is a breath of fresh air.

Bruni has been around the game throughout his life. He played as a kid and then, as a parent, would drive his own children to and from rinks.

But more than that, the Calgary lawyer has seen the sometimes troubling underbelly of a sport that’s ingrained in Canada’s cultural fabric. He started as a volunteer at the grassroots level, moved on to become the head of Hockey Alberta, which eventually led to a senior role with Hockey Canada.

When he was named executive vice-chairman in 2011, Bruni wanted his new role to result in meaningful change. He knew it needed to evolve with the rest of society and he was finally in a position to do something about it. He even coined a slogan that has since stuck with him: “staying relevant with the courage to change.”

Bruni echoes that slogan in a conversation with the Free Press about the state of hockey, its past challenges and the need for the sport to continue to evolve and become a better place for all Canadians.

And while he sees the positive impact hockey can have on children and their families, he’s not blind to the messy parts. For the sport’s culture to continue to improve, he says it must start with leadership at the top, and include meaningful dialogue with its various partners.

“I really think that there’s a huge responsibility on hockey’s shoulders, and I don’t know if the leadership realized that,” Bruni says. “I think they may realize that now, and when I say leadership, I’m talking about the board of Hockey Canada, the executive of the operations, but also the heads of each of those 13 (provincial and territorial) members.”

”I really think that there’s a huge responsibility on hockey’s shoulders, and I don’t know if the leadership realized that.”

Bruni admits hockey has been slow to react at times when dealing with issues around social change. He’s observed first-hand the reaction of colleagues who believe hockey is attacked unfairly when asked to change, which only leads to a higher level of resistance.

He points to the recent shuffling in November of the Hockey Canada board. Bruni, who heads the Board of Directors Nominating Committee for Hockey Canada, which was established in 2012, was extremely proud that the five new additions bring some much-needed diversity to the mix, including three women.

With a secret ballot, anything was possible.

“It’s a delicate process. People tend to be very sensitive that you’re being critical of them, and this is not the case…. It’s a significant step and the important part now is how this unfolds moving forward with the new board. I think there is going to be some challenges but those challenges are really opportunities,” he says.

It was an important step for hockey and one that other organizations, from not-for-profits to corporate boards to other sports, need to take. “And it’s not only gender diversity, but also people with disabilities, the Indigenous and (LGBTTQ+) communities. It’s not just to be diverse for the sake of it.”

Bruni says he believes hockey, like all sports, has had the time to reflect, especially now with play paused during the COVID-19 pandemic. He’s inspired by seeing a shift in perspectives.

“When I left the board many years ago one of the things I said was, ‘You guys aren’t going to exist in five or 10 years unless you change.’ Because you know what? There are going to be other institutions that are going to come up and there are others that are starting up,” Bruni says.

“If you want to fight the market you’re going to lose. You don’t compromise your principles or your values to satisfy the market, but you’ve got to recognize what the market is and what the market is demanding, and I think hockey has lagged behind in so many ways. I can list so many things that they’ve had to adapt to.”

One of the big issues facing hockey is its over-emphasis on top-level athletes, prioritizing them over the vast majority of players who don’t play in the sport’s top leagues.

Bruni says it’s time for a dramatic shift in philosophy. Instead of a singular pursuit of international glory, the focus needs to be more about developing participants as players and humans.

”It’s almost better as a parent if your kid is not an elite athlete.”

“No matter what the system, the truly elite athletes will rise to the top. Only a small percentage of hockey players — and in other sports, as well — make a living at the game. A very small part. It’s almost better as a parent if your kid is not an elite athlete. If they’re an athlete that’s good enough to enjoy it from a developmental and skills point of view, but they’re not elite,” he says.

“Because what happens is, regardless of what sport it is, it’s to the exclusion (of) the rest of your life. Everything else is gone to the exclusion of that sport and that’s not very healthy.

“Even kids in the Western Hockey League, not many of them go on from major-junior. You think that’s the elite of the elite but not many go on to making a living from it. And I think that, if it can be a vehicle to educate them at any level of the sport, that’s a really positive thing as opposed to really focusing on excelling and making a living at it. There’s a lot of elements to this, but I think it’s getting better. But it’s going to take time.”

●●●

Sheldon Kennedy can’t help but wonder how different his life might have been if some of the safeguards in place today to protect players from predators like Graham James had been there when he played.

But he also knows that while James spent years terrorizing him, the serial sexual predator coach is just a symptom of a much bigger issue in the game. Hockey culture, Kennedy says, allowed James to do what he did to teens for decades.

”The power and influence coaches can have over players is just incredible.”

“The power and influence coaches can have over players is just incredible. You saw it with me years ago, where one man was calling the shots and he was able to make or break me with one phone call,” Kennedy says.

“My case was obviously bad, but it’s not just about sexual abuse, either. That power and control can lead to emotional abuse and other forms of abuse, too. We’ve gotten better — hockey has gotten better, for sure — but we still have a long ways to go.”

Kennedy remains fully committed to his company, Respect Group Inc., which he founded in 2004 with friend and business partner Wayne McNeil. Its focus is empowering people to recognize and prevent bullying, abuse, harassment and discrimination with online training courses. It covers all industries where abuse could be prevalent, with a specific focus on the school system.

They have spent the last 20 years trying to help sports organizations across the country. Their programs educate groups about the various forms of abuse and their effects, and establish a way of reporting issues as they arise.

It has been a challenging exercise, Kennedy says. Although much more is known about the damaging consequences of abuse in sport, organizations are still reluctant to commit.

“One of the biggest things that we’ve done, and we’ve spent a lot of time on, is showing these organizations, holding these organizations’ hands to get them to a place to make it mandatory,” he says.

“They’re so scared to make this type of training mandatory, whether it’s ours or anybody else’s.”

The issue, Kennedy says, is organizations sometimes think that adopting such programs amounts to admitting to having a problem. Or, more commonly, there’s a fear that if they do require such programs they’ll lose quality coaches.

”Hockey has gotten better, for sure– but we still have a long ways to go.”

Kennedy says Sport Canada is a source of frustration; the federal governing body isn’t providing any guidance to its lower-level associations, leaving the provincial organizations, many of which are run mostly by volunteers, to do much of the heavy lifting.

“Sport Canada only focuses on national team coaches. They don’t reach grassroots, they don’t get to St. James minor hockey,” he says. “It’s the system; that’s not their jurisdiction. So it’s up to the provincial sports organizations to drive it down into those everyday coaches. So there’s such a lack of understanding.”

McNeil believes it could take many years before there are real changes throughout sport culture.

“One thing we’ve found is that it takes a lot of time to change culture because it’s embedded in people’s personalities,” he says.

“You can also say that it might take a generation to influence culture, as you see with some of these social issues that are emerging.”

It’s a crisp November day and Kennedy is playing with his two-year-old son Lochlin in the front yard of their Calgary home.

They pull around a sled, shovel snow and tinker with a toy dump truck as a Free Press photographer’s camera snaps away.

Once inside, Kennedy pulls out a few mementos from his days of playing junior hockey in Swift Current. There’s a large diamond-encrusted ring adorned with the Broncos’ horseshoe logo that the players received for winning the 1989 Memorial Cup, which is the championship awarded to the country’s top junior team.

He also pulls out a massive belt buckle that’s engraved with ‘Memorial Cup Champions’. But that’s about all he kept from his three seasons in Swift Current because, although he left as a champ, most of his memories from there are best left in the dark.

Besides, Kennedy is looking forward, not backward, at this point in life. He’s focused on being a support for other sexual abuse survivors, helping them find those little victories in their daily lives that allow them to continue in their healing journey.

He’s also focused on his family. Maybe Lochlin will have the same passion Kennedy had for the game when he was tearing up the Elkhorn rink as a boy dreaming of playing in the NHL.

Ultimately, he says, it will be today’s young children who will make the sport a better place.

Kennedy was 14 when he met James and his life became hell. He says while many of the educational programs in place are tailored for players in their early teens, another one, for children as young as nine, is already in the works.

That age is crucial. Although the kids are still growing and developing, they’re starting to gain confidence in themselves and their personalities are emerging.

“It’s that part of life that is so important,” Kennedy says.

“If you can get to those kids at that age, that’s going to be your greatest success of seeing a hockey culture change.”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

After a slew of injuries playing hockey that included breaks to the wrist, arm, and collar bone; a tear of the medial collateral ligament in both knees; as well as a collapsed lung, Jeff figured it was a good idea to take his interest in sports off the ice and in to the classroom.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.