Multiple-choice exam Back to school this year means very different things for three Winnipeg families

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/09/2020 (1999 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

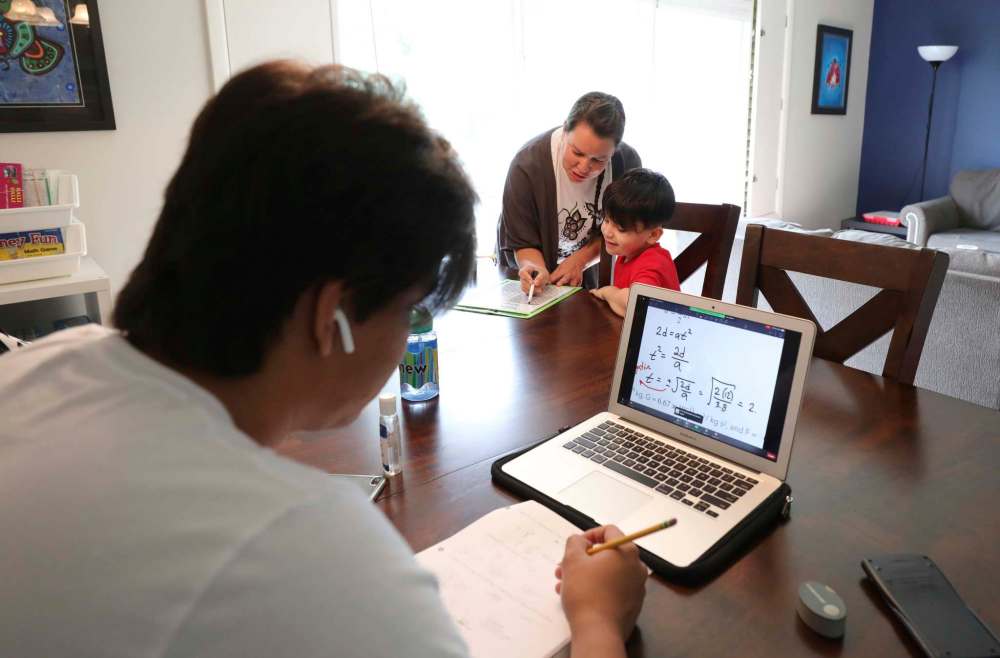

Meet the Milne-Karns, the Parenteaus and the Blum-Paynes.

Anna Milne-Karn and her moms Heather Milne and Luanne Karn live in Wolseley.

The Parenteaus — Anna, Jason and their sons Carter and Josiah — live in Silver Heights. The boys’ cousins can also be found inside, sharing meals, laughs and cultural teachings.

Across the city in Elmwood, Andy Blum, Krystal Payne and eight-year-old Emby Blum-Payne live in a house with a pink door. Emby’s grandfather Edward Payne lives in a suite downstairs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected each city family in unique ways. Throughout the last six months, workloads — for parents and their children — have been altered, social circles drastically reduced in size, and travel, celebrations and ceremonies have had to be postponed.

Differences aside, all three households share in a single goal: keeping loved ones safe — and that means they have all had to evaluate their places in the public school system this year.

“We’re generally feeling positive about our family’s decisions,” Milne says about Anna’s Grade 3 classroom attendance. “We recognize that every family is in a difficult situation and will have to make the best decision for their families.”

The options for families who don’t feel comfortable sending their children to school with masks include home-schooling and remote learning. The latter is for students such as Emby, who have been advised by health-care providers to stay out of classrooms because of virus-related risks to themselves or to others.

There are approximately 210,000 kindergarten to Grade 12 students in Manitoba. A total of 186,372 of those pupils attended public schools in the province’s 37 school divisions, according to last year’s provincial enrolment report.

Since the data is collected on Sept. 30 annually, it’s too early to know exactly how COVID-19 has impacted public schools on a provincial scale, but Manitoba’s home-schooling office is reporting a spike in interest.

As for remote-learning figures, the Winnipeg School Division — the largest of its kind in the province, with nearly 33,000 students enrolled in schools in the provincial capital — has already approved 126 students, 99 of whom are in the English stream and 27 who are in French immersion.

COVID-19 has and continues to transform education in ways unimaginable before March 11, the day the World Health Organization declared a pandemic.

Within days in mid-March, teachers swapped whiteboards for webcams. School divisions paid for internet access and distributed devices to students who didn’t own them. Others had to finish the school year using homework packages.

Now, teachers are scrambling to address the learning gaps and mental-health challenges that accompany being isolated for much of the last six months.

As the learning curves carry on into a new year, the Free Press will follow these three families to document their experiences in the classroom, with remote learning and home-schooling amid the uncertainty and anxiety of the pandemic. Much like the province’s ever-changing virus-response policies, their plans may require adjustments.

The Milne-Karn, Parenteau and the Blum-Payne families have graciously opened both their textbooks and homes for the 2020-21 school year.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

An uneasy return to school for the Milne-Karn family

A few days before the first day of school, the Milne-Karn family stopped by 7-Eleven for an end-of-summer treat. Wearing masks, they pulled the levers to fill up their cups with the variously coloured slush that is, in some circles, considered Winnipeg’s official beverage.

Eight-year-old Anna started to suck on her straw.

“Anna was drinking the Slurpee through the straw through the mask,” recalls Luanne Karn, one of her two mothers. For the record, Anna says “it worked!”

Karn uses the anecdote as an example of the challenges teachers will face this year.

From students attempting to pick their noses under their masks to face-covering trades between friends, enforcing proper public health protocols among young students will be no easy feat. An experienced resource teacher, Karn knows first-hand what working with students is like on the best of days.

That reality has made both Karn and her partner Heather Milne uneasy about sending their daughter back to school to attend the third grade at École Laura Secord.

Even still, after considering Anna’s well-being, work schedules and the value of French-immersion education, they decided it’s what’s best for them.

The family of three also lives in a different city from their relatives, so their bubble is limited to a select few friends and Anna’s school and daycare cohorts.

“There was a lot of screen time when everything was shut down — too much screen time,” says Milne, an author and English professor at the University of Winnipeg.

The contrast between how her students will learn (fully online) and how her daughter will learn (in a crowded school) is not lost on her. She and Karn had hoped the province would cap class sizes and require K-12 schools to ensure students would be separated by at least two metres in classrooms.

“We have great confidence in the teachers at her school. We think they’re going to do what they can to keep her safe but in general, the return to school has been very poorly executed by the government and by the school divisions.” – Heather Milne

They both expressed their frustration throughout the Safe September Manitoba campaign leading up to the back-to-school season.

“We have great confidence in the teachers at her school. We think they’re going to do what they can to keep her safe but in general, the return to school has been very poorly executed by the government and by the school divisions,” Milne says.

Karn adds the province has been “close-fisted about the money.”

As of mid-September, there are 21 students in Anna’s class. As for chief provincial health officer Dr. Brent Roussin’s public health orders, teachers are to enforce physical distancing whenever possible and space desks out at least one metre apart.

Anna and her peers are now required to wash or sanitize their hands frequently, stick to their assigned playground areas during recess and borrow bathroom tags to hang outside the facilities while in use so others know the capacity level.

Music, one of Anna’s favourite subjects, also looks different.

Instead of playing instruments, her class was tasked with listening to different songs and drawing pictures of how they made the students feel during the first week of school. Anna says she drew a castle when her teacher played classical music.

She wears a mask during the day even though the province has made them mandatory only for Grade 4-12 students. She has a variety of them in her wardrobe; her favourite is blue and has clouds on it.

“(Masks) are like socks,” Karn says. “We’re just going to have a lot of them.”

As they walk down Wolseley Avenue on their way to Laura Secord, the trio pauses at a crosswalk to put on their masks before dropping Anna off.

It’s a new routine they’ve become familiar with in this most unusual school year.

Room for three cousins in one home-school bubble

Carter Parenteau will spend the fourth grade studying core subjects and speaking Ojibwe with his cousins in the cosy living room of his family’s Silver Heights home. The cooking and canning lessons will take place in the kitchen during the week. On Fridays, his father will organize fishing field trips.

Some might call the Parenteau family’s plan for 2020-21 home-schooling.

A more accurate description of Carter’s upcoming year is, according to his parents, Anishinaabe-izhichigewin. Or, in English, “the way Anishinaabe do things.”

The changing colours of the leaves typically mark the start of a new school year in the Ojibwe-immersion program at Isaac Brock School for the family. This year, Anna and Jason Parenteau have chosen to keep Carter home in order to limit their close contacts and protect the elders and high-risk relatives in their lives.

“Children do not know boundaries. You try to enforce these things, but the reality is adults don’t even have those habits. Even in the grocery stores, people don’t follow the arrows,” Jason says on a recent school day.

For the time being, only teenage son Josiah will attend in-person classes part time. A Grade 12 student, he is enrolled in blended learning at the University of Winnipeg Collegiate.

“I was in denial for a while, like, ‘Oh my God, are we really going to have to home-school?’” Anna says.

She has high praise for the Ojibwe-immersion program and its teachers who are “almost like family,” so her hope is they can remain connected to the school until the threat of COVID-19 subsides.

“Children do not know boundaries. You try to enforce these things, but the reality is adults don’t even have those habits. Even in the grocery stores, people don’t follow the arrows.” – Jason Parenteau

After much planning, Anna says she has come to terms with the home-school bubble organized by the Parenteaus, Kennedys and Patricks. Together, the families — all members of Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation — have planned a schedule that will see different adults take on academic and land-based teaching roles throughout the week.

Monday through Wednesday will be reserved for core subjects including math, English and Ojibwe, as well as strategy games and baking. Thursdays will be for outdoor education and socially distant meet-ups with other First Nation family bubbles. On the weekends, Carter and peers Kenny Kennedy and MJ Patrick-Prieston will attend ceremonies and take part in cultural outings.

“A long time ago, pre-Canada or Confederation, families did what we’re doing now. We’re just looking after our children and teaching them as best as we can,” says Jason, who is Lenape from the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown in southwestern Ontario. Anna is Ojibwe, from Roseau River.

He has already started to teach the boys about tanning hides. One hide from a recent deer hunt is currently soaking in a bin in their backyard. It will soon be stretched into a drum to be used for ceremonies.

The Parenteaus have always taught their sons about the importance of embracing their Ojibwe and Lenape identities, but the pandemic has provided them with a flexible schedule to focus on cultural and land-based learning.

It has also required the adults to reorganize their shifts and for some, work fewer hours per week. Jason is taking Fridays off from his work at Dakota Ojibway Child and Family Services. Anna, who is employed at the Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre, is working remotely.

“It’s a choice between having the kids in school and still continuing to access the elders and community and family,” says mother Dawnis Kennedy.

The families have chosen the latter option.

Kennedy says it feels daunting, but she finds comfort in the knowledge they have a support network of friends and elders and she and Anna, who are cousins, learned traditional ways from their families when they were growing up.

Remote-learning option will keep grandfather safe

Emby Blum-Payne is a chatterbox.

As the eight-year-old roller-skates down the sidewalk in her hot pink wheels — a mid-pandemic purchase — she talks about her two dogs, her friends and her friends’ dogs. It’s hard to get a word in edgewise.

“She’s normally this chatty, but she’s starved for attention. She’s an extrovert,” her mother Krystal Payne says.

Ever since March 11, the day the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus pandemic, Emby and her family have been spending most of their time at home in their Elmwood neighbourhood. An only child, Emby’s interactions with other children have been limited to video calls and physically distant visits.

“We want to get a bubble so in the winter, we can go inside with Bryan, Kelly (and baby Forest), our friends,” Emby says.

Payne says they have been extra-careful because Emby’s grandfather, who lives in a semi-independent suite in their basement, is immunocompromised; his lungs haven’t fully recovered from a months-long hospital stay and intubation several years ago.

Given their situation, the Blum-Paynes sought back-to-school advice from their family nurse practitioner.

“Emby will require to stay home and access a remote learning program/option for the Fall 2020 school year, in order to prevent transmission of COVID-19 onto her grandfather,” states the subsequent medical note, which Payne submitted to the Winnipeg School Division one month ago.

The province’s back-to-school guidelines indicate division-level remote learning will be in place for students who are medically advised not to return to in-classroom learning because of COVID-19-related risk factors. There has been widespread confusion about the exact situations that qualify, but Emby has received approval.

If the pandemic had not disrupted their lives, she would be starting the third grade at École Sacré-Coeur near Health Sciences Centre.

“Unfortunately, because my dad is so high-risk, a return for us just might not be possible until there’s a vaccine or a really good treatment.” – Krystal Payne

On Wednesday, Payne received an update from the principal: WSD is hiring staff and finalizing details for its division-wide virtual school. She has yet to receive a definitive start date.

Until the school is up and running, École Sacré-Coeur has offered to prepare learning packages for Emby and her remote-learning classmates.

A frustrated Payne says it’s “mind-boggling” how few details the division has provided to families while tens of thousands of students have already returned to classrooms across the province.

Emby is currently working through the home-school curriculum Payne purchased to supplement the remote program.

“I like my project today for science. I’ll go get it,” Emby says, then vanishes, quickly reappearing with a large worksheet that has a drawing of a Fennec fox on it. She is studying an animal-classification unit.

“This is my project. It’s a fox — the littlest fox on earth,” she says.

Payne is aware that her family is privileged to be able to keep Emby home.

She took a leave from work to provide child care and plans to focus on completing her master’s degree in archival studies at the University of Manitoba and part-time work as contract research assistant this year. Her partner Andy Blum continues to commute to his full-time job with the city.

Outside, the Blum-Paynes have installed a rock-climbing wall and swings in their yard. Inside, they have set up a remote classroom for Emby.

“If the schools did all of the right things: distancing, more testing in the schools for asymptomatic students, better ventilation systems, I still don’t know (if we’d send Emby),” Payne says.

“Unfortunately, because my dad is so high-risk, a return for us just might not be possible until there’s a vaccine or a really good treatment.”

For now, through remote learning, she says the hope is Emby will be able to learn in French and stay connected to her school.

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

.jpg?h=215)