A call to serve Since arriving from Syria, Nour Ali had a desire to build communities; even his tragic death became emblematic of his mission

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/07/2020 (1971 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

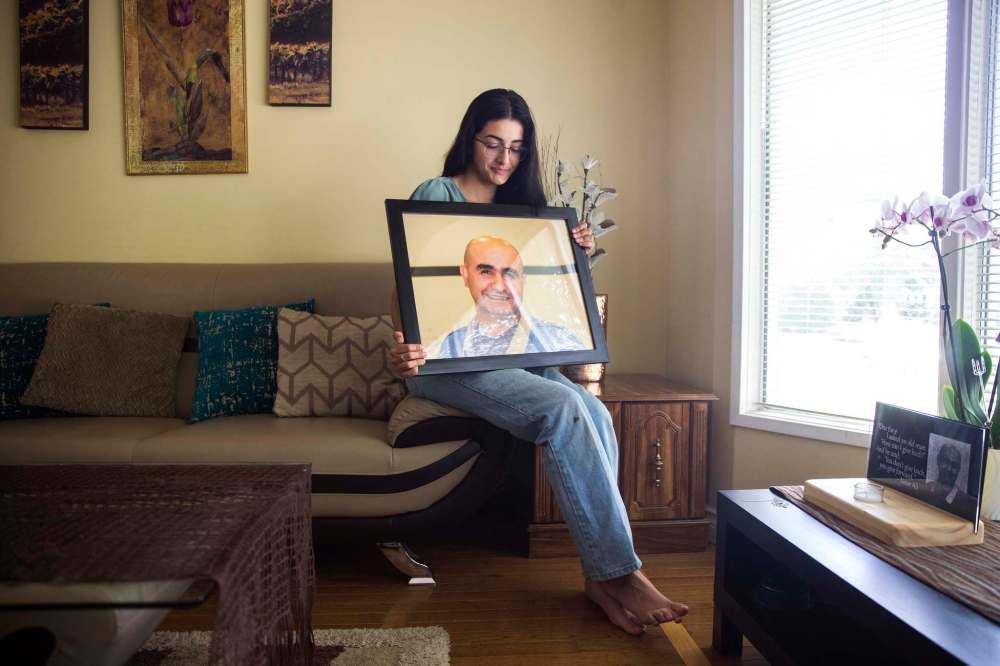

On the day that would change her family’s life forever, as Rooj Ali stepped out to greet her relatives in the dappled light of early summer, she had no way of knowing it would also be their goodbye. So it is all the more precious that this is what she remembers: the last time she saw her dad, he was laughing.

His name was Nour, which in Arabic means “light,” and that is the same word friends reach for to describe him. He was tall, with a sturdy build he’d inherited from his father. He had a presence, a way of drawing everyone’s eyes to him. At 42 he was “a ball of energy,” one of his friends says, always smiling, always in motion.

That afternoon was no exception. The family had rented a cabin in Lester Beach, close to the rolling waves of Lake Winnipeg’s eastern shore. In the nearly eight years since they’d come to Manitoba, the first Syrian family to arrive as refugees, they hadn’t always had much time to spend all together; they’d had to work so hard.

But in recent months, Rooj says, Nour had tried harder to find time to spend with his two daughters. After work, he’d ask if they wanted to go fishing, or go to Birds Hill Provincial Park. To the girls’ delight, just the night before, he announced that next year, they were going to buy a cabin of their own; he already had the boat to go with it.

He’d bought the boat a few weeks earlier, at auction. It wasn’t anything grand, just a shallow fiberglass fishing boat, but he spent hours fixing it up with his younger daughter, 13-year-old Naya. One of his friends was skeptical, joking that he’d kill himself if he tried driving it, but Nour only laughed.

That was Nour, though. He was an optimist. He didn’t worry about things like that.

So now, on a blissful Saturday afternoon in mid-June, Nour was getting the boat ready to take out on Lake Winnipeg. He loved the water, and spent as much time around it as he could, and liked to invite others. This time, his brother, a cousin, his father-in-law and his father, Hamza, were coming along for the ride.

Outside the cabin, Rooj saw Hamza arrive, and went to greet him. The 16-year-old hesitated, not knowing if it was OK to give him a hug, given the pandemic, so she awkwardly shook her grandfather’s hand instead. At this, Nour laughed, and the three spent a few minutes chatting, until Rooj turned and went back inside the cabin.

In the days that followed, she would be grateful for that last happy moment together. In truth, the teen and her dad often butted heads; she’s so much like him, friends say, and also like her mother, Maysoun Darweesh, all of them imbued with the same sharp minds, the same strength of will, the same firm convictions.

“Just like him, I don’t hold onto things very much,” she says. “I don’t really hold grudges or take things super, super personally. That makes me always return back to positive thinking and having a good relationship with the person. Because of that, I was able to have my last memory of him be a happy one.”

As she speaks, she absentmindedly toys with the delicate silver chain that hangs around her neck, twisting it in her fingers. It was a gift from a friend, after everything that happened next, and from it dangles a tiny pendant studded with sparkling faux gems in the shape of a letter “N.”

● ● ●

To understand Nour Ali, to understand how he did what he did and became what he became, maybe one has to start by looking at the points in his life where he had to become something new, and start all over again. There were many junctures like this, but in the arc of this story, none were more pivotal than Dec. 13, 2012.

That night, the Ali family landed in Winnipeg, ready to begin a new life in Canada.

Already, they’d walked a long road to get to that point. Nour had grown up in northeastern Syria, the second of six kids in a big Kurdish family. He met Maysoun at university in Damascus, where they both studied journalism. They were drawn together and, within days of meeting in 2001, they knew they would someday marry.

Maysoun is ethnically Arab, and it isn’t common in Syria for the two ethnic groups to intermarry, but their bond soon proved unshakable. They were both outgoing, with a deep passion for human rights. In December 2002, they were married; Rooj was born in 2004, and Nour started a logistics business to support their young family.

But he was also becoming politically active, invested in calling for human rights in Syria, particularly for Kurds and other ethnic minorities. For this, he was arrested by Syrian police, and held as a political prisoner. He never talked about that time in his life much, Rooj says. It must have been a dark one.

By 2006, Nour knew it was too dangerous for him to stay. He fled to Macau, a glittering resort city on China’s southern coast. The next year, as pressure from Syrian authorities mounted, Maysoun and the girls followed. Rooj was three years old at the time; her sister Naya, just a baby.

They would spend more than five years in Macau, where the girls learned Cantonese. Life was challenging, Rooj recalls: her father was gone a lot, working hard to build an import-export business. The risk of deportation to Syria loomed; they needed to find a safe third country where they could settle for good.

Then, a ray of hope. In Macau, Maysoun befriended a bible study group from a local Mennonite church. One of the pastors there, Tobia Veith, learned of their plight; her cousin, Don Boschman, was pastor at the Douglas Mennonite Church in Winnipeg, and she reached out to ask if that congregation could help the Ali family.

The answer came back quickly: yes. The church already had extensive experience sponsoring refugees, and the personal connection made it even easier. They started the paperwork to bring the family over, and settled in for a months-long wait: it would take over 2.5 years to complete the process, Maysoun says.

Finally, the day came: the family was approved to travel to Winnipeg, where the Douglas congregation was waiting.

Rooj remembers that first drive from the airport, staring wide-eyed out the van at their new country, marvelling at the snow and the single-family houses, so different from the soaring skyscrapers of Macau. She was excited, though she didn’t fully understand why, but she saw the hope in her parents’ faces.

“Our lives were saved from having to go back to Syria,” she says. “My parents knew this is where we could start completely fresh, and we knew that we had support. They were very happy to be here and I thought, ‘if my parents are comfortable, and they feel safe, then I do too.’”

Church members had spent days fixing up the family’s apartment, a two-bedroom on Edison Avenue. Heidi Reimer still remembers meeting Nour for the first time that night. The van pulled up and he hopped out, beaming: “You must be Heidi,” he said, and pulled her into a thankful embrace.

“I knew right from the minute I saw them that this is a really special family,” she says. “There was a warmth about them that was very visible. For people who are completely exhausted from travel, and they’ve been halfway across the world, and they’ve been through so much to get here, and yet, they seemed to embrace everything.”

In Winnipeg, the family hit the ground running. Within days, Reimer recalls, Nour and Maysoun had mastered using Winnipeg Transit, which they took to a blood donation clinic. They came regularly to church, where Maysoun joined the congregation and Nour, an agnostic, happily helped out around the building.

Soon, Nour found a job working for Winnipeg Building and Decorating, a restoration company owned by another member of Douglas Mennonite, Henry Thiessen. He had little experience in restoration, but he threw himself into learning the trade, asking for as much work as they would give him, often 70 hours a week or more.

Thiessen, who is now retired, identified with that drive. His own family had come to Canada as immigrants when he was 11 years old, having fled Russia during the Second World War. He knew how hard it was to build a life in a new country, and Nour’s determination impressed him. Within days, Thiessen was singing the man’s praises.

“He won’t work for us that long, he’ll be owning his own business soon,’” Thiessen recalls telling Boschman.

Years later, Nour did just that. In 2017, he started his own restoration company, calling it Thank You Canada. He focused on hiring other newcomers, so that they could get work experience in Canada, and he kept close ties with Thiessen’s business, which hired Nour’s company as a contractor.

By then, he was also becoming deeply immersed in community work. As the devastation of civil war spread across Syria, the local Kurdish community held rallies to draw attention to the crisis. Nour was quick to get involved; that’s how Allan Emre, who is originally from Turkey, first met him around 2013.

“It caught my eye how quickly he could gather people together,” says Emre, who became a close friend of Nour’s. “We did several protests at the Legislative building, and he would just jump in and get things done. Things were unfolding unbelievably fast when he was attached.”

At the time, Nour and his family were, as far as Emre knew, the only family of Syrian Kurds living in Winnipeg. That didn’t last for long. When asked to describe the local Kurdish community, Emre divides it into “before Nour, and after Nour.” Before Nour, it was a small community; after him, it had surged by the hundreds.

He became a key voice at the Kurdish Association of Manitoba, where he often urged them to think more broadly. Their mandate was to help Kurds in crisis, but Nour thought they should expand that to help refugees from every ethnic background. Emre encouraged him to take that drive and create something new, of his own.

The seed of that idea would later grow into a non-profit, the Kurdish Initiative for Refugees.

It was remarkable how Nour found his voice in the city. Only a few years in Canada himself, by 2015 he had met multiple times with then-premier Greg Selinger, pressing for more provincial support for refugees, including from Yazidi and Arab communities. Nour was “very passionate and very committed,” Selinger recalls.

Meanwhile, with the help of Douglas Mennonite and other organizations, Nour threw himself into trying to bring more families to Canada. He started reuniting his and Maysoun’s own family, and advised groups from across the province on how to sponsor refugees; not only from Syria, but from all over the world.

Nour took an active role in building these connections. Sometimes, he’d be at the airport at 5 a.m. to welcome one family, and go back at night to pick up another. He and Maysoun travelled all over Manitoba to attend weddings or celebrations, or just to be present to give advice to the community they were working to grow.

“We would finish one sponsorship of someone and he’d be like ‘OK, onto the next! What can we do next?’” Reimer says. “It’s hard work to always be hospitable, and always be generous, and always be working to the next goal. But they very much lived out that ideal that you don’t build a wall, you build a bigger table.”

This approach, sometimes, caused a little friction. At Douglas, Nour always thought they could do more, go bigger; Boschman tried to talk him down to earth. Nour encouraged newcomers to start working, sometimes within days of their arrival, even though sponsorship afforded them time acclimatize to Canadian life.

“We’d say to them: ‘we’ve committed to sponsoring you for a year. So take that year to recertify, or to get your qualifications,” Boschman says. “But Nour was all about ‘no, get off the church’s payroll as quickly as possible, so then the church has money left over to sponsor the next family.’”

Through it all, Nour was focused on what he thought was right. He never thought of himself as the leader of it all, Rooj says. But with every family he helped bring to Canada, and every program he started, and every person he helped, others began to see him that way, calling him at all hours of the day and night.

About seven months after Mohamad Bakr’s family came to Canada from Syria in 2016, they met him at a party for Newroz, the Kurdish New Year. Bakr, now 24, describes Nour as “the head” of the Kurdish community in Manitoba, and they discovered a special connection: Bakr’s mother came from the same Syrian town as Nour.

The Bakrs lived in Portage la Prairie, but Nour visited them whenever he could. When Bakr told Nour about how he struggled using English at work, Nour urged him to stick with it. “It will come,” he told Bakr, “you’re doing really good.” The family hoped to sponsor Bakr’s older siblings to Canada; Nour started planning a fundraising party.

“He had a group pretty much, he said ‘I can bring them, I can do the party, I can raise the money, I can help you guys,’” Bakr says. “We are really thankful. He was always trying to help us. But I know he helped lots of people… When I go to Winnipeg, or to see friends, I always hear stories about Nour, always.”

It had been only a handful of years since Nour arrived in Canada with nothing but his family, his vision and his mind. Now a growing community of people were turning to him for advice, for support. Looking to him as the one to lead, the one to build. The one to light the way.

“He just became a figure of importance and care because honestly, his whole life became the people,” Rooj says. “And I think that people could tell that. Because he was always there for them. He was always supporting them.”

● ● ●

That Saturday, around 4:20 p.m., Chris Feakes and his friend, Trevor Hargren, were relaxing on Hillside Beach, nestled into the eastern shore of Lake Winnipeg. Their Sea-Doos bobbed on the water nearby. The friends were just about to head out for a ride when they were paged: a boat had capsized, not too far away.

“We were in the right place, at the right time,” Feakes says.

The pair, both volunteer firefighters, sprang onto their Sea-Doos and started racing towards the scene.

Feakes knows Lake Winnipeg. A year-round resident of Victoria Beach, he has spent much of his life on the water, and he knows what it can do. The lake is beautiful, but it can also be tempestuous, changing moods from flat-glass water to crashing waves within minutes, whipped by the winds that race across its vast surface.

That day, he recalls, the lake was angry. A brisk southeastern wind would gust up to 60 km/h, raising four-foot swells tinged with white froth. The water was frigid, which meant immediate danger for anyone stuck in it; they might have as few as 10 minutes before they started losing the ability to control their limbs.

Arriving at the scene, the rescuers found a small fishing boat upside-down in the water. A man was sitting on top, and Feakes surmised he would be OK to stay there for a moment. Two others were floating nearby, one clinging to a life jacket; in the distance, a kayaker was helping another man to shore.

The rescuers focused on the two men in the water. One of them, Feakes realized, had already died. The other, he saw, was in dire condition, struggling to move and almost blue from the cold. Feakes hauled him onto the Sea-Doo, then took off racing for the shore, where rescue crews were gathering.

That man, Maysoun’s father, was rushed to hospital in critical condition, but he survived. A few minutes more in the water, and the story might have been different. Nour’s father, Hamza, perished; but with the help of the rescuers his cousin and brother made it safely back to the shore.

Soon, Feakes learned there was another man who went into the water and hadn’t come out. He turned back to the waves, scouring for signs of life. In his five years as a local firefighter, it was the most devastating water rescue he’d witnessed; he would stay out on the lake until dark, searching for Nour.

“At the time you don’t think about it. You just do what needs to be done,” he says.

On the other side of the lake, RCMP S/Sgt. Bob Chabot heard the mayday call come in over the marine radio, and pulled his team together. As RCMP Manitoba’s inland water transport co-ordinator, he was readying his crew to fill in for the Gimli-based Coast Guard, which was preparing to head to the lake’s north basin the next day.

Now, they found themselves rushing their boat across the lake.

When he arrived, Chabot and his team assessed the situation. In some water emergencies, information is sporadic; they might know only that a boater never came back. This time, the information was clear: witnesses told them how the boat capsized about 700 metres from shore, and that Nour had disappeared in the water.

Chabot knew the odds of survival were slim. But in his 29 years on the force, including the last four in his current position, he’d seen miracles before. His team towed the capsized boat to shore, and began co-ordinating a search with the Coast Guard and the Victoria Beach rescuers. Above them, a military C-130 Hercules aircraft circled.

“You always hope for the best,” Chabot says.

As they searched, news began to spread that Nour was missing. It spread in phone calls and texts sent in English, and Arabic, and Kurdish, and probably other languages too. It spread from Winnipeg to small towns in Syria, from Germany to China, and many of those who received it struggled to believe it was true.

“I thought there must have been a mistake,” Reimer says. “It just seemed so surreal, like a bad movie.”

At home in Winnipeg, Emre was hosting a few friends in his backyard when he got the news. Stunned, he turned to his guests, who came from different communities, different backgrounds, and told them that one of his friends was missing, a man originally from Syria.

One of his guests looked up. “Is it Nour?”

That was how Emre found out that his guests also knew Nour, but he wasn’t surprised. By then, it felt as if everyone in Winnipeg knew Nour, no matter who they were, no matter where they came from. That’s just who Nour was, Emre explains, someone who connected people together.

“Winnipeg is small, but this guy was making it even smaller,” Emre says.

● ● ●

By 2018, the Ali family had fully settled into their life in Canada. Nour’s business was going well, even as much of his and Maysoun’s time was consumed by community work. They became citizens that year. They’d bought a house in North Kildonan the year before, which was often filled with friends they’d invited for dinner.

The two were a “powerhouse couple,” one friend says, cut from the same cloth. Nour was most public — a spokesman for their endeavours, but Maysoun was always beside him, often handling the details and helping newcomers; she would soon take a job at the Mennonite Central Committee as a refugee settlement co-ordinator.

“She was the brains of the operation,” Rooj says. “And he was the heart and the soul and the face of it all.”

Their work made regular headlines. Journalists went to Nour for story ideas about the refugee community, and he always came back with several. He joined the board of the Ethnocultural Coalition of Manitoba. He organized big community BBQs, where Syrian families served food and chatted with hundreds of neighbours.

Of all of these efforts, the one Nour was perhaps the most proud of was the summer program for refugee children, which the Kurdish Initiative for Refugees had launched in 2016. It was an ambitious idea, bringing hundreds of kids together to practise English, take in human rights workshops, and even act in short films.

It was important to Nour that the camp show kids the breadth of cultural life in Canada. In 2018, he took them to a powwow at Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, where they met Chief Deborah Smith and learned about the struggles Indigenous people had faced in Canada, and got to dance along to the beat of the drums.

At that event, Nour met Clayton Sandy, a Dakota powwow dancer and knowledge-keeper. The two got to talking, and realized they shared many of the same values in bringing communities together. Before long, Sandy says, Nour was helping plan almost all of Sandy’s projects, including a North End party to mark National Indigenous Day.

For that event, Nour announced he knew the owners of a local ice cream shop. A few calls later, he’d enlisted their help too. Sandy can still picture the scene: all of these kids running around, some Indigenous and some born clear across the world, gleefully mingling over little paper cups of ice cream.

“I just think that Nour was one of the people that thought from the heart,” Sandy says. “We just do things sometimes even if it costs us our own money, our own time, our own family time. We just do it because we grew up like that. We know what it’s like to be in poverty, to have people be mean to you.”

● ● ●

As the search for Nour stretched into hours, and then days, the process fell into a sober pattern. Every morning, Chabot mustered his RCMP team to go over the day’s mission, and at night they’d guide the boat back to Gimli, without finding any trace of Nour. They’d assess what they had accomplished, and what to try next.

It’s tedious work, and it can be psychologically draining, but the team committed to staying positive.

“We’ll be in the boat and say ‘hey, this looks great, the wind’s going to be calmer today, it’ll be a better day today,” Chabot says. “We’re always hopeful, always. We never say ‘it’s never going to happen.’ We know that’s a possibility, but… if it’s not that day, we’re saying, ‘OK, it’s going to happen tomorrow.’”

For Chabot, the search had taken a personal twist. Friends of his knew Nour, because Nour knew everyone, so as the search went on he got messages from them, saying they knew he was trying his best. Every day, he and other RCMP members met with Maysoun to keep the family updated, which drove them to keep searching.

“When you see the hurt that’s happening, and the sadness, you really do your best to try and bring closure,” Chabot says. “Our team would have stayed as long as we had to… I think lots of police officers, we’re type-A personalities. We want to be the person who stays to the end and gets the job done.”

It wasn’t always easy. For the first several days, the wind and the waves didn’t let up, making it unsafe for divers. Instead, the RCMP team marked any sites of interest that popped up on their sonar, and continued on in the search pattern, cutting kilometre-long lines up and down the lake.

They weren’t the only ones searching. At the beach, dozens of people converged to support Nour’s family, and to help where they could. Every day, around 30 people split into groups to search on the lake in their own boats, or comb the woods along the shore, sometimes playing Nour’s favourite music as they looked.

On land, an Indigenous group held a ceremony, laying down tobacco to pray for his return. The Douglas Mennonite congregation rallied around the Ali family, organizing to keep them supplied with everything from food to emotional support. Bakr and his friends came out hours after the accident, and returned every day to search.

Every night, when they returned to the city, they longed to do more. “We’d say, ‘if we walked two more miles, maybe we’ll find him,’” Bakr says, “always we hoped.” And they marvelled at the diverse group of people that had gathered for Nour, united in this effort from a multitude of faiths and cultures.

“I was really surprised about the people too,” Bakr says. “I saw people from everywhere. Not only Syrians. There were Arabs, Kurdish, Canadians, lots of other communities. They came and they asked about him, and they really cared about him.”

The searching was hard, especially for those closest to him. Each time Emre went out looking for Nour, he came back feeling as if he’d lost part of himself in the search. But he kept doing it, because he kept thinking what Nour would have done if the roles had been reversed.

“I told my wife, ‘I’m going to look at the mirror straight and feel good, because he would have done 10 times bigger,” Emre says. “He would have rented a cottage there and say ‘we’re not going anywhere until we find our buddy. Until we were done with our mission.’”

At the cabin, Nour’s daughter Rooj tried to stay focused, coming to terms with what was unfolding.

“The second day is when I woke up and I realized, there’s no getting away from this,” Rooj says. “This is happening and this could very well would be it. That was the day I started to prep myself for what I would be doing for if I would be to return to Winnipeg without him, if he wasn’t in my life anymore.”

Even in the midst of that realization, she was struck by one fact. As the days wore on, messages would come in from all over the world, a new country almost every hour: someone in England sending their love, or Macau, or rural Syria. Many had never even met Nour, but they’d heard about him from others.

“The fact that some of them had never met him before shows how many people he reached,” Rooj says. “Because of their lives changing, it just rippled outwards. I honestly could not give you a number of how many people were trying to help him. And it just blew me away.”

On the fourth day of the search, a friend of Nour and Maysoun’s called Chabot. There was a team of Hutterites who wanted to help, she explained. They’d just returned from Alberta, where they’d spent days searching for the last of three Hutterite girls who drowned in a river, and now they wanted to try again for Nour.

Chabot was intrigued by the offer. The Hutterian Emergency Aquatic Response Team (HEART) had a better type of sonar than the one mounted on the RCMP boat, he learned; they also had a remote-operated vehicle, one of only a handful in all of Western Canada, and they’d successfully recovered eight bodies before.

After getting official approval to bring a civilian team on board, he invited them to meet at the Yellow Brick Road boat launch just after noon the next day. It was a good decision, he said later, because the search was about to change.

● ● ●

The thing about Nour, his friends say, is that he was always on the go, always going somewhere, always doing; as a result, everyone who knew him had a story, or a few, or a dozen. So in the days and weeks after the accident, these Nour stories became a sort of currency of grief, passed from one person who loved him to another.

In a way, these stories hold his legacy more than anything that made the news.

There is the story about how he once showed up shoeless at a Winnipeg grocery store, casually explaining to his family that he’d given his shoes to a homeless man, right after buying him a meal.

There’s the time in 2016, when a church group in South St. Vital needed to help a refugee family from Syria move apartments. “Call Nour,” someone said, so they did, and he just asked what they needed and when, and they were amazed when he soon showed up with moving boxes, a truck and a whole bunch of people.

They finished the move in a couple of hours. Church members asked Nour what they owed him: “Nothing,” he said.

There are all the times that, learning someone was in trouble, he jumped in his car and drove to Saskatoon, or to North Dakota, or to somewhere in small-town Manitoba. The times when a group in Arborg, which had sponsored around 20 refugee families, called Nour and put him on speaker phone so he could translate for them.

Once, a young man wanted to get married but couldn’t afford a wedding, so somehow Nour rustled up a venue in the North End and filled it with 150 people. Once, someone from the Syrian community woke up after surgery, surprised to find Nour right there in the room, working on his laptop beside the hospital bed.

When immigrant youth needed help to navigate conflicts with more conservative parents, they called Nour, and he called the parents, and within hours he had fixed the problem. When a young gay man from Syria felt excluded by that community, he reached out to Nour, who took him under his wing.

And there were all the times when his friends were left bemused or flabbergasted at the audacity of his efforts. He was unflappable, even when his plans seemed to escalate to what others perceived as unmanageable levels, and those stories too say a lot about who he was.

Once, pastor Boschman remembers, Nour asked if he could host the Kurdish New Year party in the gym at Douglas Mennonite Church. At first, he said it would be just 100 people, which the pastor thought would be fine; a week later, Nour revised that number upward, closer to 250, which Boschman thought would still be OK.

On the night of the event, Boschman was out for supper when his phone rang.

“All of a sudden (an organizer) phones and says ‘there’s some problems, there’s a fire alarm, and plus there’s a lot of people here,’” Boschman says, and shakes his head, laughing. “It was like 500 people. But this is how life goes with Nour. He comes to you with a small idea, and it grows.”

This spring, as the pandemic put Winnipeg into lockdown, Nour started looking for ways to help. Along with school trustee Jennifer Chen and KIFR volunteer Magi Hadad, he launched an initiative to deliver food from local refugee and immigrant-run businesses to health-care workers; at one point, he called Emre to chip in.

“He would call me for donations,” Emre says. “And he would say, ‘(Allan), we’re going to give food to all those front-line workers for COVID-19 at Grace Hospital. I put you down for $500.’ I said ‘buddy, if you’re going to do that, you may as well pay it, because you’re not asking me, you’re obliging me.’

“He says ‘OK, no problem.’ This is how he got things done.”

That sort of thing happened all the time, Emre says. But he never could get mad at Nour.

“You never got upset, because you knew the jewel that he was after,” Emre says. “You knew what he was trying to polish. So when he was trying to polish a diamond, obviously you would give him a rag or you’d give him a tool. He needed a tool… and money was just a tool for him, a simple tool.”

Through all of this, his friends say, it’s important to remember that Nour wasn’t a saint. He wasn’t perfect. Nobody is, and besides, if he was he wouldn’t have been such a compelling figure. He was abundantly and exuberantly human, and that’s why friends marvelled at how he kept finding new ways to help.

He was never reckless, they say, but he was confident, which is what allowed him to keep going. The confidence to start life over in a new country, and within just a few years be leading a community. The confidence to try a new trade and start his own business. The confidence to call friends up at all hours to enlist their help.

Or, the confidence to take a shallow fishing boat onto Lake Winnipeg, not really realizing the danger.

● ● ●

On the fifth day of the search, brothers Paul and Manuel Maendel arrived at the edge of the water, ready to load their gear into the RCMP’s boat. It was the 23rd time they’d set out to find a body, and they had a connection: some Manitoba Hutterites knew Nour, and had asked the Maendels if they were helping.

The journey that brought the brothers to Lake Winnipeg that day had begun more than 20 years earlier at their home in Oak Bluff Hutterite Colony, when a young boy drowned in a pond. His body was recovered by an RCMP dive team, and that effort struck the Maendel brothers; they soon took up recreational diving.

As the years turned, there were other drownings, and the brothers offered their dive skills in the searches. At first, they didn’t have much success, but that just intensified their desire to learn more. In 2016, they made their first recovery, finding the body of a teen who’d drowned near Plum Coulee.

“That inspired us even more that yes, we are a capable team, we can do this,” Paul says. “It’s not just the equipment and the ability, it’s also the mental preparedness. You have to have the right attitude. It’s black-water diving, you can’t see anything, you have to overcome claustrophobia. There’s a lot of emotions that you go through.”

In late 2018, tragedy struck Sagkeeng First Nation. A snowmobile crashed through the ice, carrying two victims with it. It was too dangerous for RCMP divers; the Maendels reached out to a search expert from Minnesota named Tom Crossmon, who arrived with a special remote-operated vehicle.

Within days of starting their search in January 2019, they’d found and recovered both of the victims.

Inspired by that experience, the Maendels decide to take HEART to the next level. They began calling managers at other Hutterite colonies across Canada and the United States, asking for donations. At last, they raised $160,000 to buy an ROV equipped with sonar and a camera, called the VideoRay Pro 5 Mission Specialist.

That summer, a man from Netley Creek Hutterite Colony went missing. The community feared he’d drowned in the pond, and called HEART to search. Guiding the ROV beneath the surface, they found the victim quickly. It was the first recovery ever made with the brand-new Pro 5 model; their fundraising efforts had been worth it.

Now, as they set up their equipment in the RCMP boat, they focused on the mission. Their tow-behind sonar — the Maendels call it The Fish — followed along, attached by a tether and swimming about seven feet from the bottom. On the screen, the texture of the lake bed spread out in stark relief, dotted by shadows of fish.

With Chabot in control of the boat, the searchers ran a pattern. They guided the boat north about a kilometre, then turned 70 metres closer to shore, before heading back south; this way, the sonar covered every area at least twice. Manuel watched the screen closely, marking any unusual sonar shadows on the GPS as they went.

They scanned for hours, until a vicious lightning storm howled over the lake, forcing them off the water.

The next day, the team suggested a new approach. In speaking with Maysoun, the Maendels had learned that Nour was a strong swimmer, so strong that his wife still struggled to understand how he didn’t make it out of the water. As they thought about that, they wondered: could he have fought his way closer to shore?

With that, they decided to start the day’s search closer to land, bringing the boat about 200 metres from shore, in sight of the trees, and the sand, and the spines of jagged rock that jut out into the water. At 1 p.m., they set out.

An hour into scanning, an anomaly caught Manuel’s eye. It wasn’t much to look at, just an irregular dark shadow almost directly underneath the boat, but it was so different than the lake bed splayed out all around it. Manuel pointed it out to Chabot, and clicked the spot on the screen to mark it with GPS.

Chabot guided the boat around to pass by the anomaly again. This time, the image was even more clear, almost unmistakeable. There on the screen stretched a long dark shadow, and near it a brightness rising from the lake’s bottom, about six feet long and narrow, like a jewel nestled into the silt.

Or: like a light, shining up from the watery dark.

The Maendel brothers readied their ROV and set it in the water, remotely guiding it down. As it neared the target, an image came up on the screen from the vehicle’s camera, and now it was certain what they’d found. For a few sacred minutes, they were the only people in the world who knew Nour was no longer missing.

In the boat, the RCMP members and HEART crew turned to each other, and shared relieved hugs.

“It’s an intimate moment,” Manuel says. “It’s a moment where we do stay professional, we are able to complete the task… You stay focused, and you stay strong for the family because they need us to be strong. I always tell myself, ‘you’ll have time afterwards, you’ll grieve with the family.’”

Using the ROV’s remote-controlled arm, they carefully lifted his body to the surface. They brought him into the boat and checked his pockets to find his identification. With confirmation it was Nour, they gently placed him in a body bag and began the process to bring him back to shore where Maysoun was waiting.

In the RCMP boat, Manuel took a minute, and felt the weight of all that had happened welling up inside him. He thought of Nour’s family, and of everything that had brought them together in this exact moment, where love, technology and training had come together to bring Nour back into the light.

He prayed for them then. He has prayed for them ever since.

“I thank God for the family, I thank God for this opportunity, and I give Him glory for that, thank Him for letting us find him,” Manuel says, as his voice catches in his throat. “It wasn’t the technology. I believe it was God leading us to be able to help in this situation. I did have to take a moment and give thanks to God for that.”

● ● ●

On a hot, cloudless afternoon in mid-July, a group of about 30 youth sit in a circle inside the Douglas Mennonite Church gymnasium, listening while KIFR volunteer Magi Hadad, 19, explains in Arabic the next group activity. Downstairs, in the basement another group of about 20 kids, all under age 10, sit cross-legged in a recreation room, watching their group leader with eager bright eyes.

The youth program that Nour started for refugee and immigrant kids still goes on, a little smaller this year than most because of the pandemic, but still infused with the dream that Nour held for it.

Three weeks earlier, they’d buried Nour and his father, Hamza, together. On their coffins were draped two flags: one Kurdish, one Canadian. They held a small funeral at Douglas Mennonite, and then a community visitation at the funeral home, where people from every background gathered to say goodbye.

At the graveside, Nour’s sister Shler thanked Indigenous people for welcoming them onto their territory. There were Yazidi prayers, and Muslim prayers, and Sandy sang a prayer song from his Dakota tradition, and Boschman gave a Mennonite invocation, and all of these prayers mingled together in the sweltering heat of late June.

And as the days passed, signs of Nour’s ongoing legacy worked their way into the world. Even in death, he brought people together. Chabot was impressed with HEART, and the mission’s success has them exploring the possiblity of working together more in the future.

Still, the hole that Nour left behind will take a long time to fill. Or maybe it never truly will. He was a “hero for the community,” Emre says, and now that hero is gone, and you can’t really replace someone so unique. Even now, weeks after the accident, they are still not sure what they will do without him.

“I’m afraid we will never find a person like him for our community,” Bakr says. “To be human, to care about people, like he was doing always.”

And sometimes, his friends wonder what Nour could have been, had he lived long enough to bring more of his and Maysoun’s plans to fruition. He could have made a lot of money if he’d wanted, friends say, but he didn’t. But given more time, he could have built something to help the whole world.

So that legacy falls to those around him to carry forward. In one way or another, the work of Nour’s life will continue. His family and friends are determined to carry the banner, and keep many of the initiatives he championed going, including the youth programs, dance groups and men’s support groups.

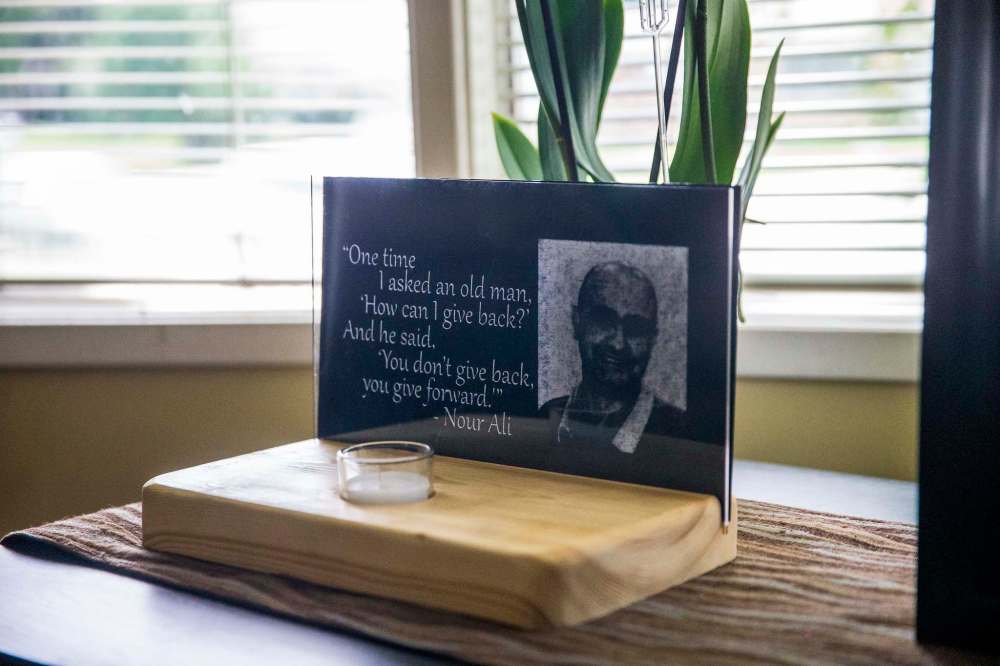

“We started this,” Maysoun says, via email. “It is a legacy. It needs to continue. We have been through hardship all our lives, but we never forget that this is not about us, or one person. It is about giving it forward, always remembering that we are all connected and supporting each other and our communities.”

To Reimer, Nour’s life stands as “a challenge to all of us” to seek out ways to help. To his daughter Rooj, he taught her to “work with what you have, and make the absolute best of it.” When asked what he learned from Nour, pastor Boschman sits quietly for a moment and then, with a smile, finds his answer.

“That we probably can do more than we think we can,” he says.

Sometimes, Rooj thinks about the search, and the funeral, and about all of those prayers that mingled over the water and the earth that held her father. She thinks about everyone who helped, and everyone who stood with them, and in those times it seems to her that there’s a sort of sense to the tragedy. A symmetry in it, even.

Once, a child was born to a family in northeastern Syria, and he started a journey that took him to the other side of the world. He gave all he could give to that community, and then he gave more, reaching out across the fissures of language or ethnicity or religion, until he slipped into the waters of a lake so vast it can dance like the sea.

There, at the end, a world of prayers found him, uttered by thousands of voices and to many different versions of God, and also to none. The prayer that is a search. The prayer that is a hug. The prayer that is dozens of people converging on the shore, until he was at last carried home by two Hutterite men in an RCMP boat.

“I think it happened for a reason, because of how many people came together,” Rooj says. “He worked his whole life to bring people together, and suddenly at his disappearing and his passing, people all came together. This one thing he really, really wanted to happen, happened. They all came, and it was just mindblowing.

“If he was able to be here and see that, he would be smiling a lot.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.