Mapmaker for memories Hobbyist historian Gordon Goldsborough hits the road every chance he gets in search of forlorn, forgotten vestiges of Manitoba's past

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/03/2020 (2104 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

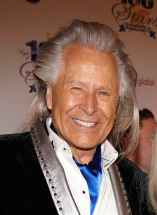

By day, Gordon Goldsborough is a mild-mannered aquatic ecologist in the department of biological sciences at the University of Manitoba.

On weekends and holidays, however, this 60-year-old associate professor transforms into a history hero — a road warrior, armed with camera-equipped drones and global positioning units, dedicated to exploring and chronicling abandoned sites throughout the province.

For the past 13 years, when he’s not busy with his day job, this affable research scientist has spent untold hours on a passion that borders on obsession — visiting, photographing, mapping and writing about everything from abandoned one-room schoolhouses and grain elevators to derelict churches, shipwrecks and federal radioactive fallout monitoring stations.

“I’m passionate about learning more about my home province,” the married father of two grown children confides between bites of a burger at Capital Grill and Bar on Roblin Boulevard. “I love the things that have changed in this province over the years. Finding out about these places tells me more about the province.

“I often start presentations by telling people, ‘I’m an obsessive person and you’ll realize that at the end of this presentation.’ I want to know every last grain elevator, every last one-room schoolhouse, where every last Ukrainian Orthodox Church is located. This is not normal, but I want to know.

“For starters, they (abandoned places) tell us how the province is changing. This information is only in a few people’s heads and they’ll be gone in the not-too-distant future. I’m fascinated to see how Manitoba has changed through the years and we show that through these abandoned sites.”

If Goldsborough’s name sounds vaguely familiar, it should. Along with being a popular professor, former director of the now-closed Delta Marsh Field Station, and oft-quoted president of the Manitoba Historical Society, he’s also a bestselling Manitoba author.

In his spare time, he’s churned out four books, two of which — 2016’s Abandoned Manitoba and 2018’s More Abandoned Manitoba — document his adventures as this province’s best-known freelance history detective.

He’s currently working on the third in the series, expected to come out in 2022. “My working title is… On the Road to Abandoned Manitoba, because not only do you have to drive somewhere to get to these places, but also along the way you could be travelling on abandoned highways.”

He’s become an in-demand public speaker, making roughly 50 presentations every year, and for the past five years, every Sunday morning, he’s been a fixture on CBC Radio Winnipeg’s Weekend Morning Show highlighting the history of abandoned things.

“Gordon Goldsborough is a walking, talking, insatiably curious story-telling machine,” longtime CBC Radio host Terry MacLeod wrote in the foreword to Abandoned Manitoba.

“He has a bottomless pool of stories — stories he has discovered, researched, photographed and written himself… No one in Manitoba has driven more back roads, trudged across more fields, poked around more decaying foundations, spotted more overlooked places, asked more questions of total strangers and snooped through more obscure historical documents than Gordon.”

This amateur sleuth has also been busy creating his masterpiece — a customized Google map that will allow anyone with access to a computer or smart device to find their way to thousands of abandoned and historic sites scattered throughout the province.

It began as an online tool — check it out at mhs.ca/map2 — to promote a dozen small museums in rural Manitoba, but has morphed into much more. Those 12 museums on the map quickly became more than 1,000 historic sites. A short time later it topped 2,000 cemeteries, monuments, buildings and other points of interest.

By the time Abandoned Manitoba was published Goldsborough, with some help from friends and colleagues, had mapped 6,200 sites. As of last week, the total sat at a stunning 7,781 abandoned and historic locations.

Gordon Goldsborough’s five must-see sites

1. Elva grain elevator This small wooden grain elevator at Elva, in southwestern Manitoba near the Saskatchewan border, was among more than 700 that once stood across the province. Their number has winnowed due to the changes that have occurred in Manitoba agriculture over the past half-century, where small elevators like this one are replaced by a few, huge elevators. The elevator at Elva is special because it is believed to be the oldest one in all of Canada, built in the fall of 1897. 1. Elva grain elevator This small wooden grain elevator at Elva, in southwestern Manitoba near the Saskatchewan border, was among more than 700 that once stood across the province. Their number has winnowed due to the changes that have occurred in Manitoba agriculture over the past half-century, where small elevators like this one are replaced by a few, huge elevators. The elevator at Elva is special because it is believed to be the oldest one in all of Canada, built in the fall of 1897. 2. Gervais bowstring bridge Bridges over rivers are a fundamentally important part of our provincial highway network, allowing us to travel with ease to many areas that were once difficult to reach. Bowstring bridges like this one over the La Salle River east of Portage la Prairie were once commonplace but their numbers have dwindled because the narrow width is not well suited to modern traffic, especially big farm equipment. This bowstring was constructed in 1919 at a cost of $7,000 borne equally by the municipal and provincial governments. 3. Port Nelson In 1915-16, the federal government began constructing a port facility at the mouth of the Nelson River, at the terminus of the Hudson Bay Railway from The Pas. They built an impressive steel truss bridge nearly a kilometre long out to an artificial island in Hudson Bay. It was later determined that the Port of Churchill was better suited to the needs of commercial shipping and Port Nelson was abandoned. A large dredge lies abandoned atop a seawall on the artificial island where it was deposited during a storm in late 1924. 4. Grainfields School In 1929, a one-room schoolhouse was built southeast of Roblin and it operated until 1967 when the remaining students were transferred to a school in town. Trustees responded positively to directives from the Department of Education to plant a shelter belt of trees around the schoolhouse to shield it from harsh winter winds. Their work was done so well that the former school building, now surrounded on all sides by dense vegetation, is now almost invisible from nearby roads. Only with the benefit of an overhead drone photo is its roof still visible. 5. Smokey’s Tree Stump A large concrete structure resembling a tree stump stands on the south side of the eastbound lane of the Trans-Canada Highway between Richer and Hadashville. The stump is believed to have been built when the highway was being twinned, between 1970 and 1972, as a lasting tribute to three young men who perished in a 1955 forest fire. The stump was to have supported a large statue of Smokey the Bear, as a reminder to always be vigilant against fires. A decision by construction engineers caused the completed stump to be off the highway so plans to finish the monument were abandoned. The site was slowly overgrown by a new forest that reclaimed the burned area.

“It does grow day by day. I’m not the only one doing it now. I get people contacting me all the time offering other places to be added to this. It seems to me a great way for this thing to evolve,” Goldsborough explains.

“Originally it started with 12 things and now it’s over 7,000 things. I have a backlog of over 1,000 things to add to it. People who know I’m doing this mapping project will send me stuff. I have a guy in West St. Paul who alone has sent me over 800 things I haven’t integrated into the map yet.”

“I’m the gatekeeper, so it has to pass muster before I put it on the map. I don’t just throw anything on the map because I believe it reflects on the Manitoba Historical Society. If it’s sloppy, if there’s any factual errors, that reflects badly… I always insist on verifying the information.”

For Goldsborough, finding out the backstory of an abandoned location, and sharing it with a growing legion of readers and listeners, is just as important as tracking down the physical location of a historically significant site.

Born in Winnipeg, he’s adamant that abandoned sites can yield valuable information about how Manitobans lived in the past, and where they’re headed in the future.

“Abandonment is a statement,” he says. “It’s a statement of priorities. You don’t abandon something you think of as valuable. Therefore, a place that is abandoned… it’s a statement that somebody didn’t think this place was worthwhile. Why? What led them to abandon it? This is the information that makes it interesting to me.

“I’m fascinated by the one-room schoolhouse. Here was an institution by which many people got their education, a fundamentally different experience than what we have today. We don’t have any one-room schoolhouses anymore. When I see an abandoned one-room schoolhouse, it reminds me of how our education system has evolved. It’s gone from this one-room school to mega-schools with thousands of students… to me, a lot of these abandoned places are interesting examples of how Manitoba has changed through the years.

“Another example would be a grain elevator. They are disappearing all over the place. There used to be hundreds of them and now there are less than 200. That is an interesting story about how agriculture has changed… the little elevator is a nice reminder of how we started. I want to go to the site of every single grain elevator that ever existed in Manitoba.”

His passion for history began innocently when a teacher at Charleswood Collegiate assigned his class to create a newspaper set during the Second World War. It intensified during his studies in biology at the University of Manitoba.

“This shows you what kind of a nerd I was,” he says, laughing. “While some people are going to the bar or playing pool or the other things you do at university, I was reading old newspapers from the 1920s or the 1940s… because I wanted to get a sense of what it was like living in the past.”

But the moment “everything changed” came about 18 years ago when his son and daughter were small and his mother arrived to babysit, allowing Goldsborough and his wife, Maria Zbigniewicz, to visit Dalnavert Museum, the small Victorian mansion nestled in the heart of Winnipeg.

“I asked the guy at the end of the tour who this house belonged to and he said, ‘Oh, the Manitoba Historical Society,’ and I said I should become a member because it would give me access to this building… my wife has said on numerous occasions she wishes she could take back that afternoon,” he recalls.

“She has described herself as a history widow. There are sports widows and there are history widows… people often say, ‘Doesn’t your wife go out travelling with you?’ No! I don’t think she has gone out with me once. She’s just not the sort of person who enjoys this kind of thing.”

In 2007, his passion for abandoned sites reached full boil when his wife, then working for an environmental consulting firm was asked to investigate sites for wind farm development near Deloraine.

“We thought we’ll take the kids and make it a family holiday,” he recalls, noting he’d done some research and discovered there was an abandoned bank vault in the area. “When the railway did arrive, it missed the town. So the town is here and the railway is over there and the guys go, ‘I guess we’ll just pick the town up and move it over.’ But they couldn’t move the bank vault because it was made out of stone. So they just left it behind. A farmer bought that site and turned it into his farm and for whatever reason decided to preserve this bank vault and put a little fence around it.”

Goldsborough and his children spent several fruitless hours searching for the vault. “We spent a couple of hours and the kids are getting rangy so finally I pulled into a driveway and went up to a house and knocked on the door. So I said, ‘Do you happen to know where there’s a bank vault?’ And the guy says, ‘Oh, you mean the one behind my barn,’ as if everyone has a bank vault behind their barn.

“I remember thinking there has to be an easier way to do this…. We have Siri on our phones and you can ask Siri to make you a dinner reservation. Why couldn’t you ask Siri to take you to the Deloraine bank vault? Well, the reason is Siri needs to know where the Deloraine bank vault is, and she needs to know the co-ordinates, the latitude and longitude. And I thought, ‘Hey, I can do that. I know how to take co-ordinates for things.’”

His idea for an online map/database providing GPS locations for historic sites became a reality after the historical society received a provincial grant to promote 12 rural museums.

The problem was the volunteer who obtained that grant had left for a job outside the province, leaving the society holding the bag. “I remember the government that had given us the grant said, ‘You either do the project or you give the money back. And we don’t give money back.’”

The original plan had been to erect billboards directing motorists to the museums, but Goldsborough figured it made far more sense to put the whole thing online and, well… why not provide the co-ordinates for all the other historic things you’ll find along the way?

“So, I thought, ‘Well, if I’m going to encourage someone to drive to Melita why don’t I also then map other things along the route so that as they are driving there — it’s a good three hours to Melita — why wouldn’t you want to stop and make a day of it? That’s where it began to snowball.”

And that snowball just keeps getting bigger and bigger. A few months back, a former student, now working for Environment Canada, sent him a fascinating site.

“She’s driving in a fairly remote area north of Hecla Island on the west side of Lake Winnipeg and she notices in the bush this culvert sticking out of the ground and she’s curious,” Goldsborough says.

“So she goes over to it and finds there’s a lid on top of the culvert and there’s stairs going down into the culvert, so she climbs down to the bottom and takes a picture. There’s an open area with a couple of bunk beds, a shelving unit, it looks like some kind of residence. Why would you have a residence about 12 feet underground?

“My first thought was it was some kind of bomb shelter, but there’s no one nearby. I did some digging and eventually found a guy at the Canadian Military Museum in Ottawa and he told me it was built in 1962 to monitor radioactive fallout because the worry was the Soviets were going to send a bomber over the pole that was going to drop a bomb somewhere in Canada or the U.S. and there’d be radiation everywhere and they’d have to evacuate major cities. They were going to build 2,000 sites all across Canada where they were going to monitor radiation, and 200 of those sites were here in Manitoba, and this thing my student found was one of those sites.”

What with Manitoba marking its 150th anniversary this year, it’s the perfect time for someone who is often considered this province’s Mr. History. He’s busy documenting sites that existed before the province did.

“If you could bring somebody from 1870 to today, what would they see they would recognize? What is here that is still from 1870? There’s churches, there’s cemeteries, there’s buildings… as much as possible I’m trying to talk about these various sites.

“If I’m a tourist and want to go somewhere that is older than Manitoba, what would you tell me to go look at? Well, if you go to Churchill, for example, you can see the Prince of Wales Fort, it was built in the 1700s, long before there was Manitoba. Or you can go to Norway House and there’s some fur-trade warehouses built in the 1830s. Or you can go to a cemetery outside Lockport.”

His main message is this — abandon your couch, hop in the car, and go visit Manitoba’s abandoned treasures, 80 per cent of which are located outside city limits.

“The fact I have seen so much of Manitoba convinces me that it’s absolutely a great place to live,” Goldsborough insists. “I love Manitoba. I was born here. I can’t imagine living anywhere else. There are so many places that are just fascinating and beautiful. If you venture out, you’ll see the things I’ve seen.”

With any luck, you’ll bump into a aquatic ecologist turned history sleuth as he traipses through the woods with three cameras, a notepad and a camera-equipped drone.

“I was stopped by the RCMP one time because one of the neighbours saw me driving around and assumed I was up to no good, so they called the cops on me,” Goldsborough says. “But I would do it over again. I would not change a single thing. As long as my health permits, I will continue to do this. I still have maybe 20 years left in me. I will continue to do it as long as I can.”

And the rest, naturally, will be history.

doug.speirs@freepress.mb.ca

Doug has held almost every job at the newspaper — reporter, city editor, night editor, tour guide, hand model — and his colleagues are confident he’ll eventually find something he is good at.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.