One man’s treasure, another man’s trash Outcry forces city to abort plans to eliminate temporary homeless shelter 'bulky wastes,' spurs overdue dialogue about mental health, drugs, affordable housing

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

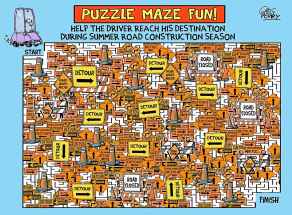

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/07/2019 (2349 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s just past noon on one of the first truly sweltering days of the Winnipeg summer, and Corey Campbell is hosting an impromptu gathering in his front yard.

Campbell’s home isn’t set up quite how he likes it yet. Just two weeks ago, when he first began looking for a new place to stay, he happened upon the riverfront lot and saw potential: it’s near La Verendrye Park, within walking distance to grocery stores and coffee shops, and is far from the parts of the city he hopes to avoid.

Most important, it was available.

The space, however, is unassuming: instead of walls he has blue tarps. There is artwork, but it sits delicately atop a nearby branch. He has no dishwasher, no refrigerator, no closet. His bedroom is his living room is his dining room.

He has been homeless since the beginning of the year. And for the time being, this small, steamy tent in St. Boniface will do.

“I had it set up a little bigger yesterday, but I scaled it down; I made it smaller so people could enjoy the view and the environment,” says Campbell, 36, gesturing to the Red River and Esplanade Riel. He’s doing his best to be a good neighbour.

Campbell’s already-precarious existence was threatened further in May when the city’s public works department issued a formal request for proposals seeking a contractor to clean up increasing numbers of temporary shelters, such as Campbell’s, sprouting up across the urban terrain as the city’s population grows, while low-income housing availability and social supports don’t.

The RFP called for the collection of “biohazardous waste” such as needles, but also for the collection of “bulky items.”

“COLLECTION AND DISPOSAL OF BULKY WASTE FROM TEMPORARY HOMELESS SHELTERS ON PUBLIC,” the request read in capital letters. “Bulky waste under this contract shall include but is not limited to items such as: (a) tarps; (b) shopping carts; (c) mattresses; (d) blankets; (e) garbage,” it went on. “The city has the right, from time to time, to add or delete (to) the list of materials.”

In short, Campbell’s few meagre possessions — blankets, mattresses and tarps providing minimal comfort and protection from the elements — are garbage to be collected and deposited at the dump, as far as the public works department was concerned.

The request, in a single line, equated the very structure that gave Campbell shelter and protection with trash. His blankets and mattresses — junk. His walls and ceilings — disposable. His way of living — as nontraditional as it may seem — thrown in the bin like a rotting banana peel.

“I feel upset about it,” Campbell says after learning of the RFP. “If we’re homeless, and we’re stuck like this, we gotta live somewhere we feel comfortable, not where the city feels is best for us.

“Down on Main Street (where the Salvation Army, Main Street Project and Siloam Mission shelters are located), some people can’t go because they’ll be threatened or jumped if they have enemies. When we find places like this, it’s just safer for us.”

Campbell wishes his situation is different, but it isn’t. Life as he knows it right now feels as temporary as the shelter he has fashioned for himself.

● ● ●

Marion Willis extends a friendly invitation.

The founder of St. Boniface Street Links, which offers support and housing opportunities for men with substance abuse issues, and Morberg House, a three-year-old housing facility on Provencher Boulevard, approaches Campbell’s tent and suggests he drop by to do his laundry and have lunch. She offers to work with him to find secure housing options.

“Come see me,” she says, handing him a business card with Morberg’s address on it. “We’d love to have you.”

“Sometimes, it’s as simple as that,” she says after. “Plant the seed, make the connection and help these people get back on their feet.”

Campbell shows up later and before he leaves says he’s hoping to get into detox to help him get off meth for good.

Most weekdays, the 64-year-old Willis hops on her 10-speed bike, flanked by Antoinette Bryan, a psychiatric nurse who has a background in harm reduction, and Morberg tenants — many of whom have been homeless and all of whom have a history of methamphetamine use. They ride along the river and try to connect people they find with available supports.

Willis finds discarded bottles, blankets and a pillow under the Esplanade; someone slept there, but it’s hard to tell when.

A large camp along the river is temporarily abandoned, but domestic life still lingers: a watercolour paint set, a pair of flip-flops, a large mirror tilted skyward, in which the glass peak of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights is visible.

Willis reaches out to Jay, who had been living there since March. He accepts her offer to shower and do laundry at Morberg. And he decides to stay, abstain from meth and attempt recovery.

“There has to be more places like this,” he says. “Thank God they came; I never want to go back.”

Street Links has been busy. An increasing number of tents and temporary shelters have appeared in St. B and Willis’s phone is buzzing with tips from residents about piles of needles and meth-related paraphernalia; the group found hundreds of unused, unopened insulin needles in a shopping cart at Coronation Park, along with a meth pipe, a blow torch and a pair of butcher’s knives.

“There has to be more places like this. Thank God they came; I never want to go back.”

– Jay

Jay, who spent many years on the street, says he understands why the public might fear the camps. “Some of those guys are messed up,” he says. “But we have to understand that for many of these people, it isn’t a drug problem — it’s a mental-health problem, and the drugs are just the medicine.”

While Willis, who has a background in social work, viewed the city’s now-cancelled RFP as an opportunity for outreach groups across the city to work together and develop a plan to connect temporary shelter residents with more stable housing options, others saw it as an obstacle to the work they’ve been trying to accomplish.

As soon as the RFP became public, groups such as the Mama Bear Clan and the Lived Experience Circle sounded the alarm. They said the terms of the document were dehumanizing, and by directly displacing people living in the shelters the city would ratchet up their trauma and instability.

“There is no exit plan,” says Al Wiebe, chair of the Lived Experience Circle. “We are setting these people up for terror.”

Wiebe is speaking from experience. In a well-documented story of rise and fall, Wiebe went from making $150,000 a year — with $1 million in the bank by his mid-20s — to living in a ratty old Mercedes Benz off Higgins Avenue for months, and then in the shelter system for a longer period into his mid-50s.

Now 64, he has become a leading advocate for homeless people, and sits on the National Poverty Advisory Council, among other volunteer roles.

He says even on the streets, people try to surround themselves with what they need to live as comfortably as they can. Moving forward with a seek-and-destroy cleanup plan and not offering housing alternatives would be devastating for a significant percentage of them, Wiebe says.

The request for proposals reminds Ward Draper, a pastor and street outreach worker in Abbotsford, B.C., of what happened in his community four years ago.

“A person’s entire life might be in that shopping cart,” he says. “To see a city like Winnipeg propose to take that away is vile and inhumane.”

Abbotsford v. Shantz, a case that reached B.C.’s highest court, dealt directly with the issue of homeless encampments. The city obtained an injunction requiring the removal of all shelters and tents erected as part of a homeless camp. The injunction was challenged, on the grounds that it violated the charter rights of the people living in the camp — a precedent-setting decision.

The court assessed whether enough alternative space was available to the camp residents, as well as whether there were barriers blocking access to that space, including shelter hours, sobriety requirements, unaffordable rental fees or poor living conditions.

Ultimately, the court concluded that if the municipality lacked sufficient shelter space, the homeless had the right to sleep in public spaces, and ruled that homeless encampments could be constructed in public parks between 7 p.m. and 9 a.m.

“A person’s entire life might be in that shopping cart. To see a city like Winnipeg propose to take that away is vile and inhumane.”

– Ward Draper, a pastor and street outreach worker

To Draper, there are echoes of Abbotsford’s precedent at play in Winnipeg, where it has become increasingly difficult to find income-geared housing. According to data from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, half of Winnipeg’s renters live in conditions below housing standards. And while rents are increasing, the availability of financial assistance has been reduced, says Kristen Bernas of Make Poverty History Manitoba.

As the city’s population has increased, the number of rental units in the Winnipeg Central Metropolitan Area has failed to keep pace: in 1992, the CMA had 58,521 units for a population of 677,000. In 2018, there were 61,199 for more than 840,000 — a five per cent increase in units paired with a 25 per cent rate of population growth.

As well, the 2018 Winnipeg Street Census, which measures the prevalence of homelessness in a single moment in time, found more than 1,500 homeless people over the course of two days in April. However, the number is likely much higher. Of the 1,500 surveyed, about 13 per cent said they were unsheltered.

Pair that with an increasingly long wait list for subsidized housing and the intersectional needs of those engaged in the shelter system — from mental health to substance-use issues to domestic violence and abuse to the lasting effects of colonialism — and it becomes clear that the deck is a long way from being stacked in the homeless community’s favour, Wiebe says.

He says he spends much of his free time walking along the river and in the Central Park area, using his street knowledge to show the people he meets that he’s a friend, not a bureaucrat.

“I was on the streets for two years,” he says as an introduction to a woman living under the Osborne Bridge who goes by the name Gramma.

Gramma is the de facto leader of the neighbourhood under the bridge, where she has a bright-green tent set up on a “yard” made of cardboard, surrounded by a makeshift fence. She has a rocking chair, a bookshelf and a system for washing her utensils. It may be a temporary shelter, but it’s a homey one.

“We’re a family here,” she says. “We clothe and feed each other and help however we can. It’s not like we’re discarded animals.”

“We’re a family here. We clothe and feed each other and help however we can. It’s not like we’re discarded animals.”

– Gramma

For a few minutes, Wiebe chats with Gramma, who prefers to live off the land, and is disappointed to hear what the city had planned to do. She’d have no choice but to pick up and find somewhere new if forced out from under the bridge.

“Sorry you feel this way,” she’d tell the workers.

Nearby, in Fort Rouge Park, directly across the Assiniboine River from the Legislative Building, a man in his 50s named William and a baby-faced 38-year-old named Dylan say they don’t want to find a home. William says he has one in Tuxedo, but Wiebe later theorizes that it’s just the desperation talking: on the street, people can be ashamed to admit their needs, and can create fantasies to distract themselves from reality.

William says the park is Indigenous land, and that if anyone told him to leave, he’d say as much.

“I’d say, eff you, show me the paperwork,” he shouts. “I’d stay.”

Five hours later, both William and Dylan are gone, a new trio of nomads setting up camp in their place. From River Avenue, the tents couldn’t even be seen.

● ● ●

Across the city, Mama Bear Clan co-ordinator Alexa Legere cried when she first read the RFP.

For three years, she had been walking the streets of Point Douglas doing outreach work with people in need, offering guidance and connection to support systems. When she was 14, Legere became homeless, sleeping in heated parkades and bus shelters. She had nothing then; now she has made it her mission to give others where she was everything she can.

Homelessness disproportionately affects Indigenous people, made clear by the street census. Although just 12 per cent of the city’s population is Indigenous, two-thirds of the 1,500 census respondents identified as Indigenous. Women made up one-third of respondents and it is significantly harder to find safe housing for women, Legere says, adding the city’s plan stood to disproportionately affect those populations.

Along with artist and activist Sharon Johnson, Legere immediately organized opposition to the RFP. A rally was held at city hall and a petition was circulated, garnering hundreds of signatures in a matter of days. An open letter to city hall followed, signed by prominent activist organizations such as Make Poverty History Manitoba and the Main Street Project.

“Nobody in their right mind would want to take someone’s home away,” Legere says, her anger apparent. “Are we really going to displace people who are already displaced?”

A few days earlier, a group of relatives she’d been helping near Norquay Community Centre in Point Douglas found their tent slashed and their propane tank ignited. Legere quickly co-ordinated an exit plan and found them safe housing.

Then, on June 20, Gabriel Coates, 44, was found dead in a Higgins Avenue park, the likely victim of fatal assault.

The next day, during a Friday-night Mama Bear Clan patrol, Legere stops where Coates — who Legere had done outreach with — was found.

“He was loved,” she says. “He was so loved.”

A short distance away, beside Pilgrim Baptist Church, a man and woman peek out of their tent and call to Legere. They were in the same park as Coates the night before. Legere hands them food and water, which she often purchases out of her own pocket, and continues along.

Soon, the patrol, about 25 strong, walks toward the Main Street Project, where, at 7 p.m., more than a dozen people are waiting to find out whether they have a space to spend the night.

Adrienne Dudeck, Main Street Project’s director of supportive and transitional housing, says the facility has a capacity of about 85, including a room for women and, in the winter, a warming station in the former Mitchell Fabrics building. Many people avoid shelters for a variety of reasons — some prefer to live on the street to reduce the chances of conflict, or to maintain a sense of independence.

The centre’s approach is harm-reduction focused and does not require its clients to be sober. Each night, Main Street Project’s van patrol connects with 100-plus people. It runs 365 days a year on minimal funding, providing support to the Winnipeg Police Service and Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service.

All the organizations doing this type of outreach function on shoe-string budgets; by the time the patrol loops around to the west side of Main Street, there are no more sandwiches or water bottles left to hand out. The level of need is profound.

Legere seems energized by the fight against the RFP, and has a meeting set with Mayor Brian Bowman the following Monday.

Bowman says he didn’t read the RFP prior to its release, and neither did city councillors, says Fort Garry Coun. Sherri Rollins.

“When I saw RFP, I thought, ‘There’s a lot of work we have to do to disrupt the systems that criminalize the poor,” Rollins says.

“I was angry, I was disappointed, and I wasn’t alone. The language surprised me,” she adds. “It inadvertently criminalizes vulnerable people.”

● ● ●

On June 25, the meeting goes as Legere had hoped: the mayor and the public works department, which had accepted pitches for the contract, agree to cancel the request. Instead, Bowman says officials will work with local advocacy groups under the co-ordination of End Homelessness Winnipeg — a city-funded initiative — to develop alternative solutions.

Stakeholders meet at city hall and discuss increasing the number of sharps disposal containers on the streets, something both Wiebe and Legere identified as a priority.

And they talk about boosting efforts to de-stigmatize the temporary shelters and about drug use, Dudeck says.

“I think the fact that the city was willing to meet was a win,” she says. “It’s huge that we’ve had two meetings to discuss, and if our organizations don’t have decision-making power, it’s important that we’re at the table.”

Having a seat at the table for discussion is a positive development. But there’s a prevailing sense that the discussion should have taken place before the request was issued, stopping this mess before it began.

● ● ●

Notwithstanding the city’s decision to cancel the RFP, to be homeless is to be continually forced into motion by others who prefer to ignore the reality of their existence.

Whenever Jeff gets comfortable, it seems, someone else gets uncomfortable. If he sits down at a restaurant for a coffee, the manager comes by to tell him he can’t sleep. And as often as six times a day, if he’s sitting on a walking trail, a police officer comes by to tell him to move, as he is in violation of city bylaws that govern camping.

Jeff, 45, is sitting in the shade near the Norwood Bridge with his possessions in a cart beside him. Two officers approach him and his friend Rebecca — his sister, he calls her — telling them they need to move, immediately. Street Links arrives at the same time the police did.

“We’re going to come back here in 20 minutes or half an hour, and if you guys and your stuff aren’t gone, then we’re going to have to make you leave,” one says. “Go get treated, get looked at, get services. But if we come back, we’ll make you leave.”

Jeff, who has spent three years on the street, stares straight ahead.

“Our job isn’t so much the social aspect,” the officer continues. “Our job is the legal aspect of it. We don’t make the laws, we enforce them, and if we’re contacted by a private citizen of the city, we have to do our job.”

Jeff nods.

“I’ve never been in your shoes, I can’t imagine how much it must suck, but we have to come along and do what we’re empowered to do,” the officer says.

He suggests they go to the Salvation Army or to the Main Street Project, but both Jeff and Rebecca feel unsafe going there. The officer says if he knew more places to send them, he’d direct them there. (Later in the week, Rebecca went to Morberg House and Willis has since connected her with safe housing.)

A bystander interjects: “When you say, ‘We’ll move you,’ what do you do then? What’s the course of action?”

“It really depends on what they’re doing,” the cop says. “If they don’t get up and move, we’ll move them and their stuff.”

“If they can’t be here, where can they be?” the bystander asks.

“They need to be someplace else,” the officer says before walking away, adding Jeff’s cart is the property of Safeway.

Jeff gets emotional.

“It happens three, four, five, six, seven times per day,” he says. “I just have to keep picking up and moving, and I have no clue where to go next. I’ve had people tell me they’ll come with bulldozers or slice up my tents. They’re literally destroying our property or threatening to just to get rid of us. How is that legal? That’s what’s happening. It’s bull.”

Sometimes, he says, it’s like people care more about the cart than the person pushing it. He shakes his head, wipes away a tear, and begins to walk in the opposite direction.

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.