Post-traumatic mess eradicator It takes a strong stomach, specialized skills and a lot of protective gear to clean up after a violent crime or unnoticed death

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/05/2019 (2399 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

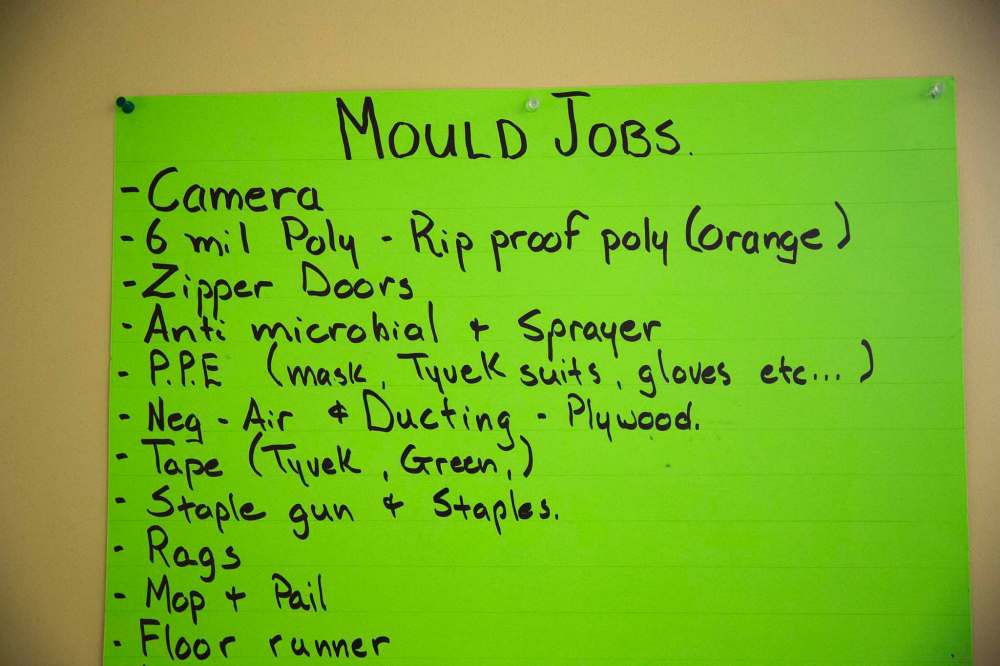

In the back rooms of the Winnipeg branch of property-restoration company WINMAR, co-owner and manager Scott Rose runs through a verbal catalogue of all the equipment he and his team use to clean.

As he walks from room to room, the 40-year-old with an affable disposition points out the body suits and respirator masks hanging on the walls, and then makes his way over to some large trunks full of supplies his technicians take to each location.

He squats down and opens a case, showing a few more items, such as gloves and various cleaning implements before pulling out a large bag packed with plain old cotton swabs.

Rose pauses for a moment and then casually says, “These are actually important… you know, for the blood and fluids in small spaces.”

Right.

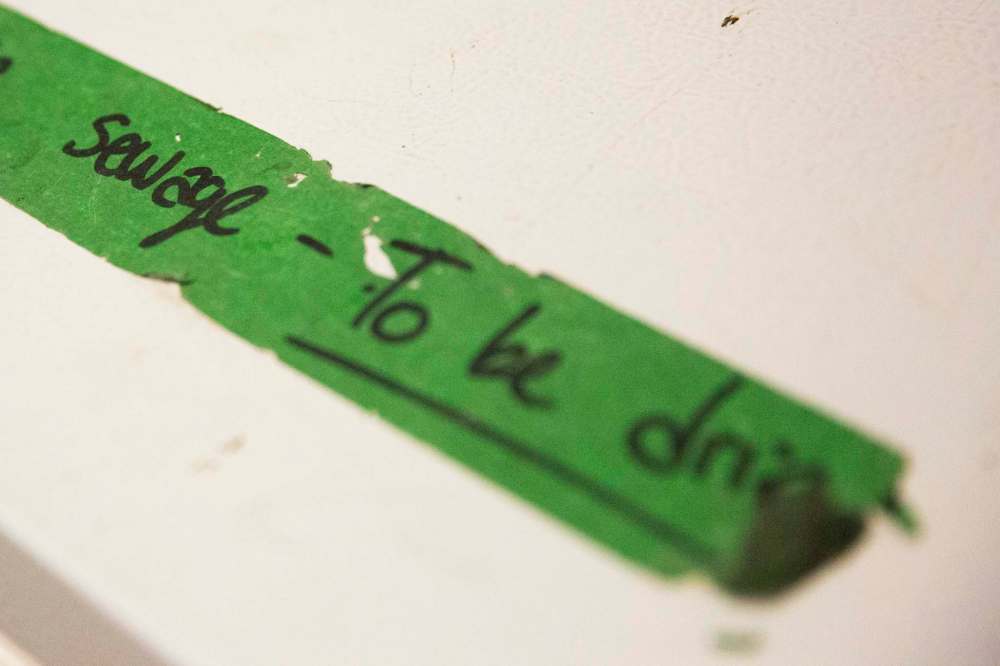

In addition to the host of traditional industrial and residential cleanups — mould, sewage, fire and smoke damage — Rose and his team are also hired to clean up trauma scenes.

Classifying a scene as a trauma can mean a lot of different things; it could mean a homicide or some other violent crime took place, it could mean a death by suicide or an attempted suicide happened or it could mean someone died in their home by way of an accident or natural causes and wasn’t discovered for a while.

Regardless of the circumstance, when a trauma has happened in a home or business, someone has to clean up the aftermath.

It’s a profession many people don’t even realize exists; until, that is, they are in need of it.

Many assume police are, in some way, responsible for cleanup if the space is also a crime scene. That’s not the case.

“The majority of that falls to the next of kin, who we obviously give advice to, as to the best way of cleaning something up, or recommendations… but in the grand scheme of things, a lot of the cleanup is either done by professional companies that exist out there right now.

“Beyond that, what we clean up is the mess that we make, but essentially we don’t have large involvement in cleaning up of scenes,” says Sgt. Brian Neumann, who has been part of the forensic investigation team at the Winnipeg Police Service for 11 years.

“A 10 per cent bleach solution will clean up a lot of that. Excessive material, you may have to remediate the surface, replace the carpet and wood. There’s a reason why we say things ‘smell like death.’

“That’s a smell that doesn’t go away.”

•••

So what do you do if someone has died in your home and you are in need of remediation services? The first step is to call your insurance broker.

Some home insurance policies cover part of the cost of remediation, which can vary widely, from something in the neighbourhood of $600 up to $15,000 for more severe cases.

CSI: Winnipeg

Sgt. Brian Neumann has been with the Winnipeg Police Service 17 years, and has spent the last 11 of those years as a forensic investigator.

To put it bluntly, he’s seen stuff.

Sgt. Brian Neumann has been with the Winnipeg Police Service 17 years, and has spent the last 11 of those years as a forensic investigator.

To put it bluntly, he’s seen stuff.

“I think everybody secretly wants to be a CSI person, so given an opportunity to actually do it just really gave me that ability to have a workplace where any day, anything can happen,” he says.

“I’ve been involved in a lot of different types of investigations, from the most mundane and simple, to some very complex and interesting national and international significant investigations.”

When the WPS is called to a crime scene, investigators can spend anywhere from minutes, to hours, to days, to even months on site, depending on the type of the scene and whether it’s related to other scenes they are investigating.

As the case unfolds, a botched cleanup job from a suspect often helps point police in the right direction, Neumann says.

“Our goal, essentially, when we attend scenes is to collect everything; a full and thorough investigation will involve that. We do pull up floorboards, drywall, we pull up carpet, disassemble furniture. Sometimes what makes my job interesting is that we are usually following an attempted cleanup… and people aren’t generally that good at cleaning up,” he says.

“As a general rule, people are not as clean as they once were. The white-glove treatment is not necessarily the litmus test that most people use nowadays, but that is something, when we’re going in and looking, people’s poor attempts at cleanup are a good indicators there might be more for us to look for….

“It’s a win-win when people try to clean sometimes because bodily fluids have a way of getting places that are hard to clean.”

Neumann also notes the the types of crimes people commit likely hasn’t changed very much since the start of humanity.

“I can’t tell you if anybody ever went through the caves at one point in time and tried to clean up the messes, but realistically speaking, the human mind still works very much the same way; do something bad, you’re best bet of not (getting) discovered is to try and clean it up. Some are good, some are not so good.

“That’s what keeps me employed.”

— Erin Lebar

The Free Press reached out to a handful of local home insurance companies, and each one had a different answer ranging from no coverage to partial coverage to coverage dependant on the cause of death. Regardless, you’ll want to know where you stand before any cleanup commences.

The next thing to be aware of is the possibility of being displaced for a few days. Again, depending on the condition of the scene, trauma cleanup can be a lengthy and incredibly detailed job in order to get a home or business to “be back in service,” and completely rid of any dangers, including a form of bacteria known as mycobacteria, which carries pathogens that are known to cause serious diseases such as tuberculosis, hepatitis and leprosy, among others.

“Normally an elderly person will pass away and no one will find them, unfortunately, for a long time and then the process with that is pretty involved, because you essentially have to wipe down the whole house. You have to cut out the floor where they were because the body fluids will sink and seep underneath them, because gravity pulls everything down and through, there’s a very distinctive odour,” says Rose.

To do this, trauma scene remediation technicians have an arsenal of tools and protective gear. They wear full-body suits and respirators to protect against various types of blood- and air-borne pathogens, booties to cover their steel-toed shoes and multiple sets of gloves, as sometimes more than one layer is needed.

They use construction tools to tear out walls, rip up carpet and floorboards and dismantle furniture when contaminants have seeped in; they use complex cleaners that help break down enzymes and disinfect surfaces; they use high-powered filters to eliminate (as much as possible) the extremely unpleasant odours in the air; and, when there are porous materials that just can’t be cleaned deep enough to save, they dispose of them following the regulations dictated by the province.

“It’s a very detailed, conscientious cleaning effort,” says Carey Vermeulen, an Ontario-based instructor with the Institute of Inspection Cleaning and Restoration Certification, a non-profit organization that works to establish global standards for all branches of the cleaning industry. The organization offers a series of certification courses on various cleaning topics, including trauma-scene remediation.

To receive certification in trauma scene remediation, a technician must complete a course, such as one offered by the IICRC, that involves both written and hands-on training. Vermeulen, who has been in the cleaning industry since 1980, says the IICRC trauma remediation course is quite new and much of the two-day intensive curriculum revolves around safety concerns for the technician on site.

“The technicians that go in to do the work, their personal safety is the main issue; the body suits, gloves, eye protection, respiratory protection (is) the same as you would (wear) for mould,” Vermeulen explains.

“It’s not like we’re dealing with bodies, that’s taken care of by the coroner, we’re dealing with the aftermath of somebody who has bled badly, bled out sometimes, or people who aren’t found for a week or two weeks, and now the decomposition of the body is 100 times worse. And the respiratory protection, you know, respirators that cover your whole face have specific cartridges that block out that smell.”

“It’s not like we’re dealing with bodies, that’s taken care of by the coroner, we’re dealing with the aftermath of somebody who has bled badly, bled out sometimes, or people who aren’t found for a week or two weeks, and now the decomposition of the body is 100 times worse.”

Other topics include the microbiology of human fluids, which biocides and antimicrobial chemicals to use, how to control “that smell,” how to dispose of materials properly and how to manage a trauma scene after significant time has passed when putrefaction has started to take place.

And then there’s the hands-on training.

Vermeulen says instructors often spatter artificial blood, hog’s blood or cattle blood on a surface, allow it to dry, and then guide trainees through proper cleanup techniques.

During his training, Rose also had to learn the proper way to clean up brain tissue that has had time to dry on a wall or other surface.

“And we’ve done that (in the field). You have to scrape it into a pan and throw it into a special bag for proper disposal,” he says.

***

So, how and why does someone end up in the trauma cleanup biz? For a lot of technicians, Rose included, it starts with work in the other branches of cleaning, such as mould or fire restoration, before making a transition to trauma.

He started his career in remediation when he was offered a position managing a mould restoration company where he met his current business partner, Brian Dudek.

Mould cleanups evolved into sewage cleanups, and then the pair was approached by WINMAR, a national restoration company, to buy the franchise in Manitoba, so they did, opening locations in both Winnipeg and Brandon.

One of the services WINMAR offers is trauma-site remediation, so Rose did the necessary training and added it to their list.

“It just came with the territory, I don’t mind doing it. There’s something satisfying about cleaning very messy things. I don’t know what it is,” he says with a laugh, before describing a few of the worst scenes he has attended in his career. (The grisly details won’t be included here… you’re welcome.)

“There’s something satisfying about cleaning very messy things.”

Rose seems relatively unaffected by the occasional — but intense — gore he encounters. However, a part of the IICRC’s training course focuses on psychological issues as they relate to both the worker and the surviving family or occupants of the residence. Rose encourages his staff of about 40 people to talk to each other if a job has hit them particularly hard.

“We don’t want to divulge information externally, but we do encourage our staff to talk amongst each other, because it is traumatic. All of them have a health spending account they can access. I’ve never seen anybody adversely affected yet, and if I did, I would do what I could to help them,” says Rose.

“The main thing they talk about (during training) is talking about the jobs, because the post-traumatic stress is the most dangerous aspect of trauma cleaning.”

Vermeulen adds: “They are forewarned of that emotional effect and you should try to separate your feelings about it from the work itself and focus more on personal safety and getting the work done.”

WPS’s Neumann, too, understands the personal difficulties that can come along with a job that involves attending trauma scenes as often as he and the cleanup teams do, but such as with any occupation where one is exposed to trauma more frequently than the average person, it becomes necessary to figure out a way to separate work life and home life.

“With the expansion into research about (post-traumatic stress disorder) and that aspect, I don’t think anybody can completely disconnect themselves from what you see and what you do, but I think I probably equate it more to being an ER doctor. If you know what your job is and you know what you could or may be exposed to, then you can compartmentalize that in a certain way. Mainly because it’s a job function, it’s something that’s occurred and you have a goal, your end goal is to do X, Y or Z,” says Neumann.

“As opposed to John Q. Public walking down the street and granny is walking across the crosswalk and gets hit by a car. The exposure to that, though in the grand scheme of things I’ve maybe seen in my career may not be all that extravagant, but to that person, that’s the worst thing that will ever happen to them in their life. So I think what a lot of is just quite truly, for me personally, that is my work, that is my job, that is what I do for a period of time and I’m hoping to come out the back end of it still well adjusted and normal and able to interact with people in the public.”

“It’s not cracked up for everybody. If you have the stomach for it, it has a lot to do with that. “

But this kind of work certainly isn’t for everyone, and Vermeulen advises anyone considering a career in trauma-scene remediation to really think carefully about the dangers, the difficulties (and, apparently, the alarming cocktail of odours) and to proceed with caution.

“It’s not cracked up for everybody. If you have the stomach for it, it has a lot to do with that. Some people just gag and can’t do it. I relate it… the easiest way for the average person to understand it (is) if you can imagine a house has a sewer backup, so now there’s sewage, potentially raw sewage, visible raw sewage; not everybody can clean that up, either, so it takes a certain person, a certain personality,” he says.

“There’s probably a majority of workers in the field who prefer not to do it. Most of these people come from cleaning water damage, mould cleanup, fire and smoke damage, that’s their background, so part of that training, the initial question is, ‘Do you want to do this? Do you want to try this?’ Because not everybody can.”

erin.lebar@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @NireRabel

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.