Power surge Manitoba Hydro's thirst for power nearly destroyed Fox Lake Cree Nation. Decades later, the northern community pushed back and won

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/03/2019 (2457 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

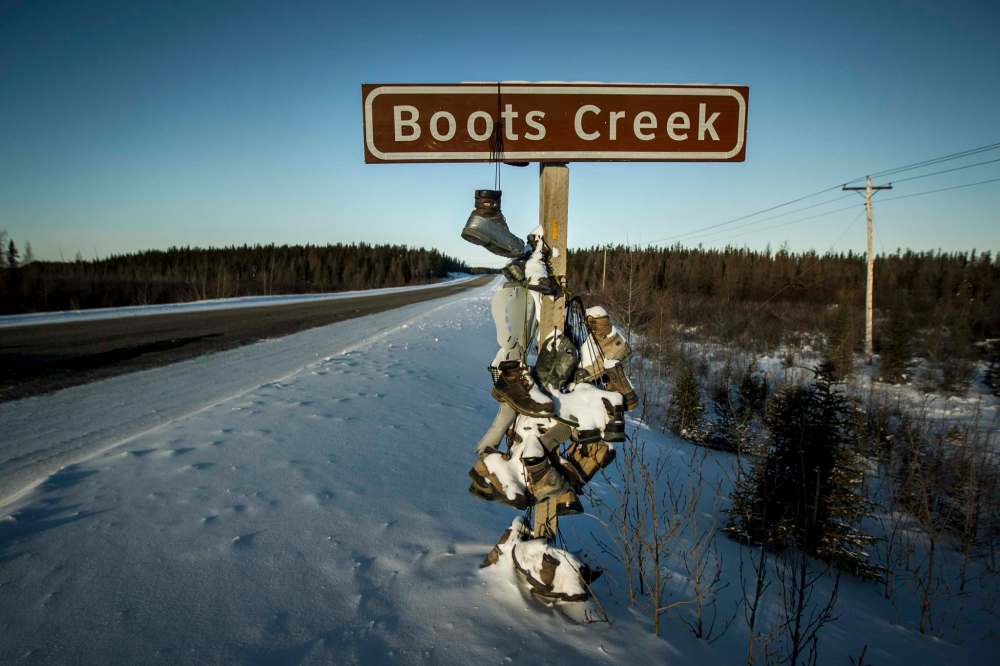

FOX LAKE CREE NATION — One of the northernmost highways in Manitoba cuts a hard line through the thick boreal blanket of trees, a dull ribbon splitting the jagged reliefs of black spruce and jack pine and the trembling aspen that stand naked for winter. It cuts onwards until it reaches the Nelson River, and now travellers must make a decision.

Take the south fork and you will cross over the spine of the Long Spruce dam, passing under the silent obelisk of its soaring spillway tower. On one side, hidden for now under a seasonal crust of ice and snow, the pent-up river splays out almost to the horizon and rises nearly to the road, 35 metres above its throttled downstream to the east.

Or, you can take the north fork and skirt the stifled river as it rushes to mingle with the frigid waters of Hudson Bay, 100 kilometres northeast. Take this route, and you will pass another dam, the utilitarian trailers of a Manitoba Hydro camp and, before that, the turn-off to Fox Lake Cree Nation land, the 98-acre reserve that locals call Bird.

That’s where Clara McLeod was on Aug. 21, 2018, when the Clean Environment Commission’s report dropped. Like everyone else in Fox Lake, she didn’t know it was coming; there had been no warning from the province that its investigation into the impact of Hydro development was about to be made public. She found out when she turned on the news.

There, splashed on the screen, were the unvarnished details of her community’s pain. It was a condensed version, packaged for viewers to easily grasp the basics of the story: how decades ago, Hydro workers had inundated this small Cree community and, in their wake, left a trail of violence and abuse.

“It was a shock too, right when it came out,” McLeod says. “It was a very difficult, emotional day. After we did everything, we made sure we debriefed. We sat together, we talked about it. It was just us being together, to be able to pour your heart out in regards to what happened. And then us coming together like, ‘OK, well, let’s talk about this.’”

Six months later, the jolt of that day has settled, a little. It is a clear afternoon in early February, and the brilliant winter sun bounces off the snow and into the windows of the band headquarters in Bird, where McLeod has her office. Squinting at the light, she thinks back to how the CEC report’s release once again shook Fox Lake’s world.

At 37, McLeod knew the nuances of the story. As a child growing up in nearby Gillam, where Hydro had staked its presence in the North, she “never really (had) any bad experiences,” she says. To her, it was just home, a place where everyone knew everyone, where Cree kids played with their friends at Hydro-worker parents’ houses.

Yet as Fox Lake’s development co-ordinator, she also knew the elders’ stories about what happened after Hydro first landed in Gillam in the mid-1960s. She’d sat with them, and heard their pain. In early 2018, she’d helped organize their testimony before the Clean Environment Commission, and she knew there was still more to say.

So when the report came out and journalists started calling, a part of her wanted to tell them everything she knew about what her community had endured, and how it had changed them. Then she thought of the Fox Lake elders, whose lives were layered by the struggles of the past like rings on a tree, and she bit her tongue.

‘I was getting phone calls at home, and I was getting phone calls at work,” she says. “I’ve always wanted to be part of a voice, working here and living here for so long. I think it was, ‘OK, well, where do we want to take this? Where do we want to go from here?’ I felt, ‘Oh, if I could just spill everything, I would. But I’ll just say ‘no comment.’”

The commissioners had not come to Fox Lake. They had travelled to hear testimony in York Factory and South Indian Lake; they’d even visited Tataskweyak Cree Nation, 160 kilometres from Gillam along the rugged Provincial Road 280 that links it to Thompson. But they never went to Fox Lake, underneath where the great dams had risen.

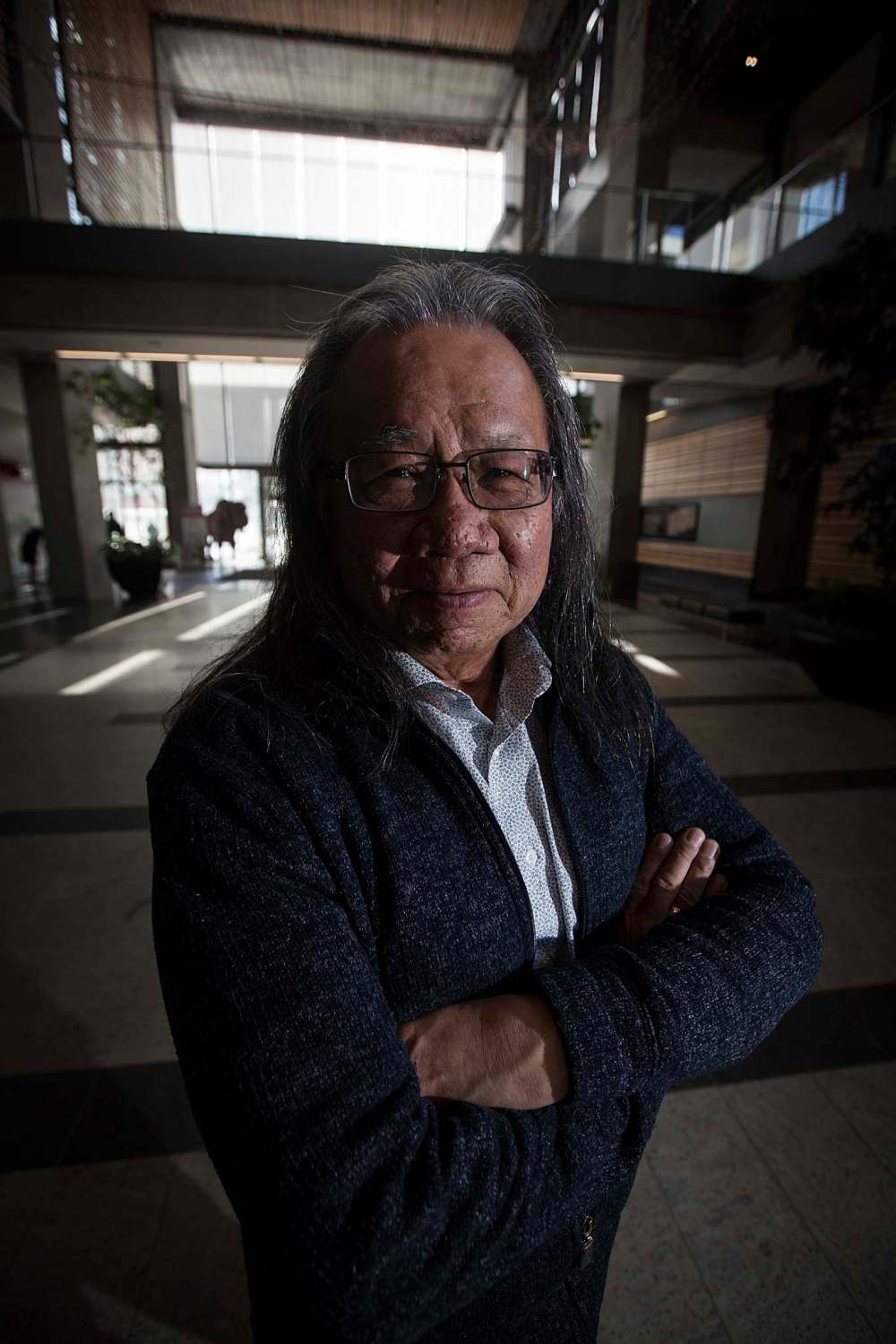

To Fox Lake Chief Walter Spence, it was simple: “They forgot about Fox Lake,” he says, during a break between meetings at Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakinak’s Portage Avenue office. But band staff had kept an eye on the commission’s progress, and management reached out to ask if they could still testify to what Hydro had done.

The commission offered to pay for about a dozen people to travel to Winnipeg. McLeod helped pull the trip together. Some of the elders weren’t able to go; she helped prepare those that could. She made a Powerpoint presentation, to show just how deeply Hydro development had disrupted their existence and the land around Gillam.

In the middle of January 2018, the Fox Lake delegation boarded a flight for Winnipeg. The mood was apprehensive.

“We didn’t know what to expect,” McLeod says, thinking back. “We had members who didn’t want to go because they wouldn’t have felt anything would have come out of it. For speaking so long, and telling our stories for so long, to some people it was, ‘Why do they want to hear?’”

Now, in front of a panel of commissioners appointed by the province, Fox Lake’s people told their story again. The elders spoke first, then the middle-aged folks and the youths. The stories they told mapped out a flood of historical abuse, in its own way just as powerful as the watery deluge that swamped the river when the dams closed.

Elders testified how, during the construction rush of the 1960s and ‘70s, they saw Hydro workers use alcohol to exploit girls, and laugh while they raped Fox Lake women. How Cree people had been beaten, insulted, arrested for no reason. How RCMP officers had taken women to jail and held them there to be sexually assaulted.

None of these stories were new. The Fox Lake Cree had told them for nearly five decades, including to a previous inquiry in 1999. They’d gathered elders’ memories into oral history collections and an unreleased documentary, keeping them safe so that future generations would always have a record of what happened.

But when the province released the CEC report that morning, followed by a hastily-announced press conference, Fox Lake was caught off guard. Since 2016, the community of about 1,200 people — half of whom live in Gillam or Bird, the other half mostly elsewhere in Manitoba — had been focusing on their wellness plan. Now, they were thrust into the glare of a provincial spotlight, and the subject was not their health, but their trauma.

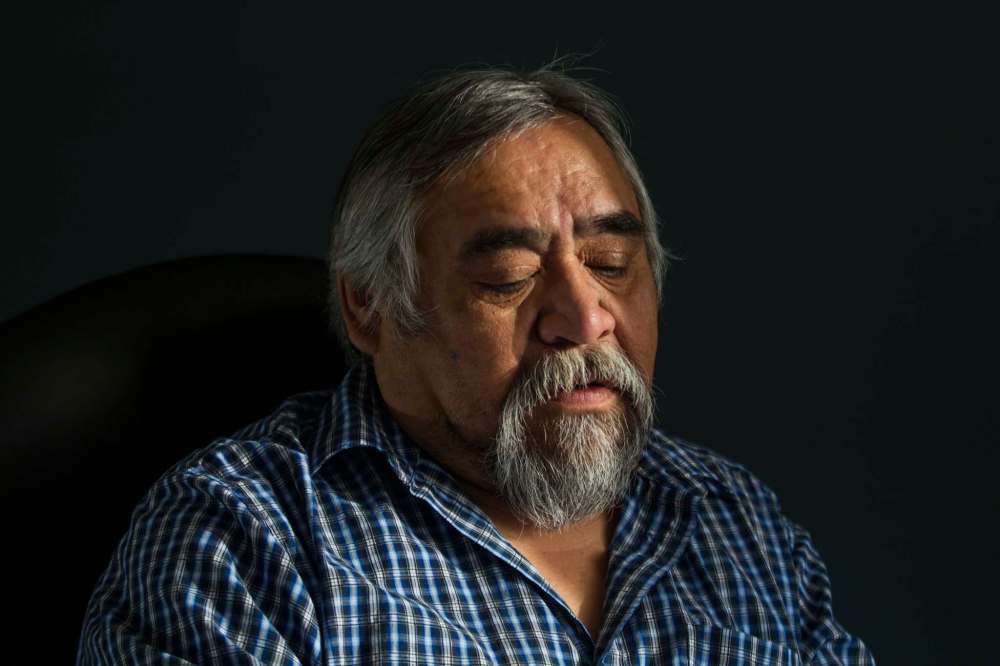

From Gillam, Chief Spence was cautious about engaging the discussion. When reporters called, he said little; but behind this quiet facade, Fox Lake leadership was immersed in a flurry of action. They knew something pivotal had just happened, but to rush headlong into it might bring an even more painful sort of attention.

With that in mind, Spence and his team made a decision: Fox Lake members were, of course, free to speak to the media about the report if they chose, and some did. But the community’s leadership would not speak at length about what had happened to their people, until they were absolutely certain what they wanted to say.

“It was like opening a wound,” Spence says. “We had no notice. ‘Bang,’ I was already contacted by media. We pulled our team together and decided we gotta strategize on what we’re going to do…. So that was the focus, on how we’re going to help our members go through this. We didn’t want our community, our members to get hurt again.”

So as news cycles turned over the testimony, Fox Lake’s voice faded from the stories. When the province asked the RCMP to investigate the abuse allegations against RCMP and Hydro workers — a request turned over to the Independent Investigations Unit and the Ontario Provincial Police — Spence offered no comment.

It’s not that Fox Lake didn’t have a story to tell. It’s just that it wasn’t the one the headlines were telling, frozen in the pages of a government report unceremoniously splashed out for public consumption. The abuse is part of what happened to them, but it is not who they are, or who they have been or what they are becoming.

Their story is far older than that, and much newer, too. Older than time, and as young as the children who scamper to classes at Fox Lake School. It is a story of how a tiny northern community stared down one of the most powerful entities in the province and won; a story about how they learned to survive the end of their world.

“To be beaten down so small, and to come back up, and to thrive, that’s what I want them to know about Fox Lake.” – Clara McLeod

“(Winnipeggers) saw all the negative stuff,” McLeod says, softly. “They don’t see our close-knit ties here. They don’t see our programming here. They don’t see how far we’ve come. To be beaten down so small, and to come back up, and to thrive, that’s what I want them to know about Fox Lake.”

There is a word in the Cree language, “êkosi.” It arrives at the end of every story, and in the way of many Cree terms, it carries shades of meaning that English needs many words to explain. “That’s it” is sometimes how it’s translated, or “it’s finished.” Or else, it becomes something like, “Goodbye; that’s all there is to say.”

More than 50 years since Hydro landed on top of the Fox Lake Cree, Manitoba was finally ready to listen to what the people there had to say. And for a little while after the CEC report came out, it seemed that their voices might be slipping into the background again, out of the wider public awareness. Off of the record.

That’s not what was happening, though. The Fox Lake Cree aren’t at their êkosi yet. Not by a long way.

A river forever changed

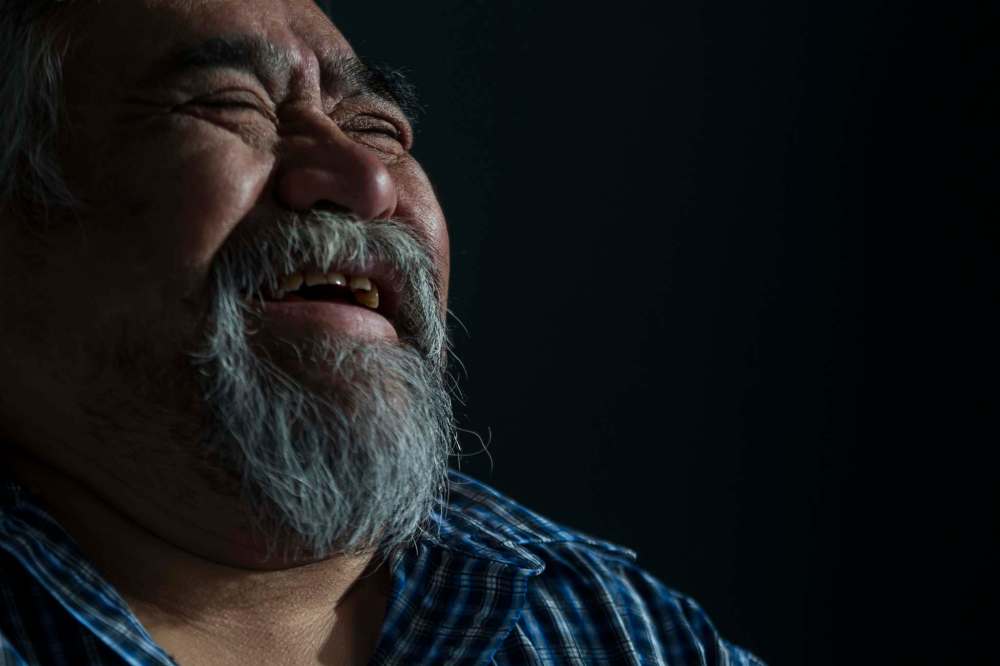

Before he will pose for a picture, Zack Mayham takes off with his walker, scuttling down the hallway of the tidy Gillam home he shares with his granddaughter, grandson-in-law and young great-grandchild. His visitors trail after him, offering to help him on the way, but he waves them off brusquely; he likes to do things on his own.

Timeline

1913-1916: Surveys identify the Nelson River as a source for future hydroelectric development. At the time, Canada lacks the technology or logistical capacity to develop it.

1930: Under the Natural Resources Transfer Act, Ottawa hands jurisdiction over vast swaths of land once controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company to the government of Manitoba. The agreement requires provinces to respect First Nations hunting rights and reserve land.

1947: The Fox Lake Cree are federally recognized as an independent band and signatory to Treaty 5. They request a reserve in their home area of Gillam. This request bounces between government officials, who send a surveyor to “walk out” boundaries of a potential reserve. In the meantime, the Cree are considered “squatters” on provincial land.

1964: Manitoba Hydro’s attention has turned to the Nelson River. A consultant’s report notes that the river, regulated by Lake Winnipeg, “contains the greatest undeveloped hydro-electric potential remaining in Manitoba.” The province and Ottawa are so impressed by the report that they renew a cost-sharing agreement to develop new dams.

1913-1916: Surveys identify the Nelson River as a source for future hydroelectric development. At the time, Canada lacks the technology or logistical capacity to develop it.

1930: Under the Natural Resources Transfer Act, Ottawa hands jurisdiction over vast swaths of land once controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company to the government of Manitoba. The agreement requires provinces to respect First Nations hunting rights and reserve land.

1947: The Fox Lake Cree are federally recognized as an independent band and signatory to Treaty 5. They request a reserve in their home area of Gillam. This request bounces between government officials, who send a surveyor to “walk out” boundaries of a potential reserve. In the meantime, the Cree are considered “squatters” on provincial land.

1964: Manitoba Hydro’s attention has turned to the Nelson River. A consultant’s report notes that the river, regulated by Lake Winnipeg, “contains the greatest undeveloped hydro-electric potential remaining in Manitoba.” The province and Ottawa are so impressed by the report that they renew a cost-sharing agreement to develop new dams.

1966: Manitoba designates a 1,996-square-kilometre swath of land as the local government district of Gillam. It is the largest LGD in the province, more than four times the size of Winnipeg. This same year, construction begins on the Kettle dam, which will eventually flood more than 22 square kilometres of land, including some of the most important hunting and fishing areas for Cree people along the Nelson River.

1968: Instead of a reserve in what is now the Gillam LGD, the Fox Lake Cree are assigned 26 Crown lots within Gillam for housing. They will continue to fight for a reserve in the town, where they had lived since long prior to Hydro’s arrival.

1973: Construction begins on the Long Spruce dam, which will flood another 13.8 square kilometres of land in the Gillam area.

1976: Workers begin construction on the Limestone dam, which won’t be completed until 1992. This year, the population of Gillam hits its peak with nearly 5,500 people in and around the area, many of them temporary workers living in camps.

1977: The province signs the Northern Flood Agreement with five different First Nations whose territories were impacted by regional Hydro development. Among other things, the deal provides land in exchange for territory that was damaged. Fox Lake approaches the province to be included but it is signed without them.

1985: After years striving for their own reserve in the area, the Fox Lake Cree are allotted a 39.5 hectare reserve, called the Bird reserve, about 50 kilometres northeast of Gillam. Many of the community members move there, although about half of them remain in Gillam.

2004: Fox Lake Cree Nation and Manitoba Hydro sign an impact settlement agreement, recognizing some of the damage done to the community.

2009: After more than five decades of pushing for reserve land in the town of Gillam, Fox Lake is given 3.21 acres. It is a tiny fraction of what they would have received, if their original claim to a reserve in the town had been approved.

2016: Following a pivotal blockade in response to Hydro encroachment on ceremonial land, Fox Lake and Hydro negotiate a landmark agreement that sees Hydro fund several positions to support better relationships between the company and the band, as well as to support other endeavours important to the First Nation.

When he returns, he is wearing a moose-hide jacket, its leather softened by time and festooned with swirls of blue and red beaded flowers. His late wife Beth made it as a Christmas present many years ago. On his bedroom wall, there is a portrait a guest painted of him once, and he’s wearing the jacket in that image too.

At 91, Mayham is the longest-lived of all Fox Lake elders. In the tradition of many Cree families, he was raised by his grandparents, following the traplines that criss-crossed the forest. He has been south of The Pas just once in his life, when he went to Winnipeg for an event. The rest of his days have belonged to this northern “askîy,” the land.

And he was out on the land one night in 1970, when the first Manitoba Hydro dam closed over the Nelson River. He and his fishing partner had tied their boat on the water and made camp in view of the ridge called Môsokot, named for how it looks like a moose nose. They heard a rustling in the dark and thought a moose must be near.

That sound was actually their boat, pushed upwards by rising floodwater. When Mayham awoke, it was to a river he no longer recognized: the Kettle dam had begun to inundate more than 220 square kilometres of forest. In time, the swollen river swallowed up Cree graveyards, washed away fish spawning grounds, smothered trappers’ cabins.

This was not the world Mayham knew. He’d been raised in the familiar pattern of the Inninuwak, the Cree people. He grew up hunting with his grandfather, praying in the forest each morning over a Cree-language Bible. When he grew up, he followed work and game all over the region, eking out a life on the land wherever he went.

Eventually, he settled near the town that the Cree knew as Kwaskimakuh, or “where the trains turn around.” Settlers called it Gillam, after an 18th-century fur trader, but to many people who lived in the region it was known simply as Mile 326 on the 820-kilometre (510-mile) railroad line that ran from Thompson to Churchill.

The Cree had a good life there, near the banks of the Kichisipi, the great rushing river that white settlers called the Nelson. In those days, an elder once said, there was no such thing as poverty. The concept had no meaning. Everything the Inninuwak needed was around them, and had been for countless generations.

The land provided, to those who knew how to live with it, and the Inninuwak’s flesh and bones were built of that labour. They ate little store-bought food; speaking in Cree, Mayham recounts how his grandparents bought only sugar, some tea and packages of flour. Almost everything else they consumed came from the land.

Food was plentiful. The rivers teemed with fish — anjawpeowak (pike), okâwak (pickerel) and, especially, the thrashing namao sturgeon, some of which weighed 40 kilos or more. In Gillam, Fox Lake children would scamper from their houses to splash in the babbling Kettle River, catching wriggling trout with their hands.

Vast herds of caribou drifted through the region, a migration path that took them right through town. Many years later, grandparents would tell grandchildren about how you couldn’t even put laundry out to dry during those seasons, because the caribou would dash through the yard and carry off lines of washing in their antlers.

The forests were thick with game — moose and wâpos (rabbit) and lynx. In the summer, families gathered the tiny, sweet strawberries that grew wild in the bush, savouring them as they worked. Hunters brought fresh meat to elders who could no longer hunt, and when one family fell on hard times, others would help prop them up.

To the Cree, this way of living, familiar and cyclic, is mîno-pimâtisiwin, the good life. The concept is broader than English can easily explain, and inextricably intertwined with both language and culture. It is how the Cree know to exist in the world, the sum total of everything they learned about the askîy over thousands of years on it.

Understanding where fish spawned in the river, how to safely wrestle namao into a boat without tipping it over, how to treat elders: all of that is the good life. And when Fox Lake CEO Robert Wavey’s father used to put down bullets as a prayer offering after a successful hunt, well, that was mîno-pimâtisiwin, too.

“Our governance is built around our spirituality and that relationship,” Wavey says. “It’s hard to explain that. (In English), I use words like ‘stewardship.’ There’s no such thing in our comprehension as stewardship, but we use it so others understand. It’s not stewardship, it’s a way of life. It’s just the way it is.”

Well into the early 20th century, it seemed that good life would continue. There were no roads into Gillam then, and not many white people, either. Railroad workers and their families, mostly, and on holidays they held parties as a community and everyone mingled together, playing baseball on the dirt roads and laughing late into the night.

The Inninuwak were proud of the relationship they had with what was then the Canadian National Railway. They’d always adapted to the changes that came to their land, and this one was no different: the fur trade had given way to the tracks that ran through to the port of Churchill, ferrying cars loaded with grain back and forth.

It was a good match. The CNR had no interest in the askîy or its riches; it just needed workers to tend the rails who didn’t shrink from the sharp northern climate or the vastness of its reaches. For the Cree, who had lived there since time immemorial, the North was neither too remote nor too cold; it was, quite simply, home.

So many of the Inninuwak worked for the railroad which, in turn, built them houses close to the tracks and paid decent wages. Even better, the work itself didn’t conflict too much with mîno-pimâtisiwin, so their way of life kept its pace. Men brought rifles with them when they went out on rails and returned home bearing fresh game.

Sometimes, kids would hop train cars, going joyriding to the next stops down the line. When they rolled back into Gillam, irate parents would chide them to stay away from the tracks, but they weren’t really too mad. There was nothing to be afraid of, really: the North was their backyard and they knew everyone on their land.

And it was their land by heart and by presence, if not yet in formal title. That part was coming, they thought: after being federally recognized in 1947, the Fox Lake Cree sought to have their Gillam community set aside as reserve land. One year, a surveyor came and walked out the boundaries of the territory they were to receive.

Years passed, and that hoped-for reserve never came. In Ottawa, there was reluctance to create new reserves: in 1955, an Indian Affairs official sent a letter to a colleague, noting that “there has existed doubt as to the wisdom of extending the Reserve system, on the ground that it is outmoded and tends to delay integration of Indians.”

Letters flew back and forth between government officials, discussing the issue. The Fox Lake Cree, they wrote, were “squatters” in the area around Gillam, the territory they had lived on for generations. Indian Affairs began to prefer the solution of allocating about 20 housing lots for the Cree, with no mention of making it reserve land.

Meanwhile, the Cree had little choice but to wait, hoping the land would soon be theirs. They weren’t allowed to vote in Canada until 1960, and had no voice in government affairs. What they didn’t know then was that far away, the machinery of powerful entities was beginning to move against them. Their lives were about to change.

It started with residential schools. Trains whisked children far away, to schools in Dauphin or Brandon or beyond. Some youngsters managed to avoid that fate: when Lynda Neckoway was a girl, someone took her to the Gillam station to wait for the school-bound train. Suddenly, her father appeared, and quickly led her away.

“Mots kasipwahtan, batima eh wechewitan, Nitanis,” he told her, in Cree. “You’re not going away unless I go with you, my daughter.”

So Neckoway never went to residential school, which she later understood as a mercy. Many of the kids who did go would come back each summer, bristling with an anger she couldn’t then understand. Some began to lose the Cree language, severing their connections with elders who, for the most part, spoke little or no English.

As with other Indigenous communities, the impact of residential schools was itself catastrophic. But for the Fox Lake Cree, the greatest trauma in their lives was yet to come. Unbeknownst to them, Manitoba Hydro had turned its attention to the generating potential of the Nelson River, and plans to build dams were ramping up.

In 1966, Manitoba set aside a 1,996-square-kilometre swath of land as the local government district of Gillam. It is the largest LGD in the province, more than four times the size of Winnipeg; that year, Hydro began building the Kettle Generating Station, the first of three giant dams to rise in sequence on the Nelson River. The $8.7-billion Keeyask project, slated to be completed in 2021, will be the fourth.

In the ensuing months, thousands of Hydro workers descended on Gillam, overwhelming the Inninuwak’s quiet community. It started as a trickle at first, just a handful of surveyors, and then it became a flood. Before 1966, only a few hundred people lived in Gillam, the vast majority of them Cree. At the peak of construction in 1976, there were about 5,500 living in the area, most of them young white men from the south, streaming up to make a quick buck.

“It was a big difference, a big change all of a sudden,” says Lloyd Kirkness, who watched Hydro sweep over the town on his summers home from residential school. “All of a sudden there was a big — I won’t say chaos — but it was just like we were invaded. Everything was just coming. And our lifestyle changed, everything changed.”

The shift left the Cree reeling. Overnight, it seemed, their community had rules they’d never been told about, places they couldn’t go, people whose ways they didn’t understand. When Neckoway was 16, she and her aunt went to use one of Hydro’s new laundry trailers, replete with shiny new washer and dryer machines.

The machines cost a little bit of money to use, and her aunt figured it would be OK if they used them. It was their community after all, and they’d always shared things like that before. So they were shocked when a man came in, bristling to see them in the trailer, demanding they take their laundry out of the machines and leave.

“Get the f— out of here, you f—ing squaws!” he barked.

They gathered up their clothes and walked home, hearts racing, not sure what to think about what they had seen.

The pressure kept building. To make way for streets and buildings to service Hydro workers, the town of Gillam bulldozed the Cree families’ houses, demolishing the friendly community they’d made beside the tracks. They were moved into what they called matchstick houses, a row of humble dwellings jammed in one corner of town.

Those houses were supposed to be temporary, the Cree learned later. They had no electricity or running water, and from where they stood, they could look out and see the big, brightly-lit Hydro houses rising around Gillam. Wavey was about 18 when that happened; he took a Polaroid of the first five rebuilt homes, to remember.

“You could see the outhouses (of our houses),” he says. “And in the background, all the new Hydro houses, with electricity and everything, when they rebuilt the whole town around us. And here we were, right in the middle of the town, with no sewer and water, and no electricity.

“I should have kept that picture,” he adds, with a sigh. “What did that say about this mega-project being built, and we didn’t have hydro?”

Nothing that was theirs was kept sacred. When Gillam decided to build a hospital right over the grave of one Fox Laker’s deceased 12-year-old child, the grave had to be moved; Enoch Ouskan still remembers the day he and three other men had to go dig up the simple wood coffin, shovels struggling to open up the hard, frozen ground.

Everyone who was around at that time has a story: something done to them, their family or their friends. Alcohol flowed freely around the Hydro workers, young and far away from their own social structures. Most of the women in Gillam were Cree, and that story often ended in painful ways; the men, too, became targets.

“I’ve seen and heard of men getting beaten up by the police for nothing,” Neckoway says. “And sometimes it’s them even walking down the street with a case of beer, and getting beaten up for that. And they’d say, ‘Well, as soon as you saw them putting on the black gloves you knew what was going to happen to you.’”

As the Cree wrestled with new limits on their lives, the dams along the Nelson came online. The Kettle dam was first, followed by Long Spruce in 1979 and Limestone, the largest, in 1992. Together, they annually send an average 20.6 terawatt hours of electricity out of the region, almost enough to power the entire province for a whole year.

When the dams were finished, most Hydro workers packed up and left, taking the money they’d earned with them. They had no investment in the community, and there was no reason to stay. The population of Gillam stabilized at about 1,200, and the Fox Lake Cree tried to pick up the shattered pieces of the life they once knew.

But the pieces could not be so easily mended. The askîy had changed, clear-cut and scarred by Hydro development. The caribou veered off their old migration paths, fleeing the noise. The moose drifted away, too. The Cree’s favourite hunting grounds had been destroyed, and what trapping areas remained soon became crowded.

The fish dwindled from the rivers, which had grown murky with sediment, their spawning rapids erased by the dams. What fish still swam in the water were different. The namao had become discoloured; their flesh, once tender, grew squishy and tasted strange. The province started testing the fish for rising mercury levels.

Every day, the life was being sucked out of Fox Lake. The mîno-pimâtisiwin they knew was slipping away. The community began to splinter, as some Fox Lakers headed to Thompson or Winnipeg, looking for work or education, or just to escape the tension that every day threatened to pull the community apart at the seams.

Some Fox Lakers found their escape in alcohol and drugs. With jobs hard to come by and their self-sufficient ways of life severed, some became dependent on trickles of social assistance. Husbands took their anger out on wives. The community had borne an immeasurable trauma, and now they found themselves struggling to survive.

“A lot of the people started losing a lot of their life skills in regards to going out on the land,” Neckoway says. “Those are our resources out there that we use. Like we used to go picking berries, and just doing little things, going for nature walks with the kids, going swimming with the kids and just enjoying that way of life.

“When people start coming into the community and start setting up new rules, saying, ‘This is the way you’re going to live, this is the way it’s going to be,’ it becomes too much for you, because you don’t know how to handle it,” she continues. “So with taking away the spiritual aspect, the way of life started to go downhill.”

A porch light flicked on in Winnipeg. A refrigerator hummed in Winkler. The cities of the south grew so bright they glittered like yellow diamonds on the plains, so bright that the astronauts who were then just beginning to circle the planet could see them from space, and southern Manitoba thrived and grew rich on this power.

More than 700 kilometres away, in the shadow of the great dams that straddled and choked the Nelson River, the Fox Lake Cree told their stories. Only the trees heard them. The trees, and the silent steel golems that loomed over the tops of the spruces, holding aloft the lines that spirited pinesew iskotew — thunder fire — to the far end of the province.

Through those lines, the fates of Fox Lake and the south were inextricably connected. They were tied to each other now, though most Winnipeggers didn’t know it, and maybe in a different world those lines would have borne more than just electric power. Maybe they would have carried the truth of that relationship, some knowledge.

The Inninuwak tried to send that down the lines. But for more than a half-century, nobody on the other end was listening.

“It’s been a really, really, really great challenge for our people,” Wavey says of the destruction that Hydro wrought. “Not that we mind challenge, but that was much too large. We don’t mind a little bit of challenge, because without challenge, what’s the point? You have to strive for things. But what happened, it was horrific.”

The Fox Lake Mafia

To this day, Robert Wavey still can’t quite figure out how it happened. All he knows is that one day in 1971 or ‘72, he was helping his buddy Tom Nepetaypo fix a fence, when one of Fox Lake’s band councillors came by and said the chief wanted to see the two young men at the band meeting in Gillam that night.

Wavey, just 21 years old, had never even been to a band meeting before. But in those days “what the chief said went,” he says with a laugh, “so we went.” What happened next is still a bit of a blur; somehow, by the time they walked out of that meeting, Nepetaypo was the new chief and Wavey was the councillor.

Suddenly, the fate of their whole community rested in their hands. And Wavey turned to Nepetaypo and wondered what the heck had just happened, but there was no turning back; a few days later, the outgoing chief showed up at their office with a few boxes of documents and unopened mail. It was their problem now.

Five decades later, chatting at a downtown Winnipeg coffee shop between meetings with Hydro officials, Wavey understands better why they were chosen. They were some of the community’s first high school graduates, and — through residential school — they’d spent time immersed in southern Manitoban cities.

“That’s what I do recall,” he says. “That’s what they were talking about, wanting somebody who could walk in both worlds, and I think that’s how we got on council, Tom and I. We at least could speak some English, and had some exposure to the outside world. And we were familiar with our own culture and how that worked.”

Still, they were young and untested. They wore blue jeans and denim jackets, and community members took to jokingly calling them the Fox Lake Mafia. That first year, they received a grant for a few thousand dollars; when, at the end of the year, they hadn’t spent it all, they returned what was left to the federal government.

“I still get a kick out of it,” Wavey says. “It wasn’t long until you were spending that much before you woke up.”

Over time, they learned how to guide the community. They went to university to upgrade their education. And they started trying to alert authorities to what Hydro had done to Fox Lake’s land, and its people; Wavey — who would go on to serve as the province’s deputy minister of Indigenous relations from April 2015 to September 2016 — recalls raising the issue at one 1970s meeting with then-premier Ed Schreyer, but the concerns seemed to go nowhere.

“We talked about our way of life, and all the destruction, and how the caribou no longer came,” Wavey says. “And I remember the Hydro guys in the room saying, ‘Well, they’re never coming back. What are you complaining about?’”

At that point in time, Fox Lake was a First Nation without land. They’d never secured the reserve in Gillam, where their people had lived for so long, where a surveyor had once walked out what was hoped to become a spreading Cree territory around the tracks. This, Wavey came to understand, was the root of their struggle.

“We weren’t told that the local government district of Gillam said there would never, ever be a reserve in the town of Gillam,” Wavey says. “Nobody told us, thank goodness. Because back then we may not have pursued it in that state of mind at the time, and where we were back then. Of course, now we wouldn’t stand for that.”

If their rights to the land had been recognized, they thought, then maybe Hydro development wouldn’t have been able to sweep them aside so easily. If they hadn’t been considered “squatters” in their own homes, they would’ve had a voice in what happened to their community, a seat at the table, some leverage to ensure their protection.

And when Manitoba signed the 1977 Northern Flood Agreement with impacted First Nations, a deal that, in part, protected Indigenous rights and offered land in exchange for Hydro-impacted regions, maybe Fox Lake would have been included. Though they had reached out to the province, the deal was ultimately signed without them.

“With the government of Canada, that has been our biggest issue, is this reserve that we never got in the town of Gillam,” Wavey says. “That resulted in us being labelled squatters. All the protections that (having land) might have afforded the people, and mitigated some of the abuses that we suffered and endured in that whole period of time.”

In 1985, some of Fox Lake’s efforts to secure a home for their people were finally rewarded with the creation of the Bird reserve, 53 kilometres northeast of Gillam. Many community members moved there, looking for a retreat from some of the problems in Gillam. Neckoway’s husband helped build the first houses on the new reserve.

“Out here you can get more into the trapping and hunting,” she says. “Over there (in Gillam) it was different, because you couldn’t. Because Hydro was telling you what you can do, what you can’t do. It was better to move away from there. So we moved here, and life became a little bit easier.”

The work is far from over. In 2009, the band finally received 3.21 acres of reserve land in Gillam, enough for some housing for their elders and a gaming centre. Now, they are fighting for the larger reserve in the town they once sought, but never received, a home for their people in the place where their families had lived for generations.

The federal government has recently been open to discussing the issue; those negotiations are ongoing.

“If we can get a reasonable settlement of that issue, that will settle the past,” Wavey says. “It doesn’t settle the impacts of that past. So part of the settlement has to look at wellness for the community at large. I think we have shown to be pretty resilient. In spite of everything that happened to us, we’re still around, we’re still fighting the good fight.”

“People really need to understand the price has been paid for that power.” – Robert Wavey

Once, about 30 years ago, Wavey remembers trying to warn what was then Indian Affairs about the cost of letting First Nations languish. The human cost of developing Indigenous lands for electricity or wealth, he told them, would not hurt his people alone. It’s just that they bore the brunt.

“People really need to understand the price has been paid for that power,” Wavey says. “The price has been paid by the most vulnerable. So when you see people on the streets, or in the North End, what’s their story? Where did they come from? Why are they here? How many of them are here because of what happened up north?”

He pauses. Outside the coffee shop window, downtown Winnipeg huddles in the cold. Nearby, the sleek lines of Manitoba Hydro Place stretch to the sky, a gleaming glass testament to raw power, the $278-million house that electricity built.

“The price of power, and who paid that price,” Wavey says, again. “And we’re not paying any more.”

A landmark deal

Mike Lawrenchuk pulls his Hydro truck to a stop and hops out of the cab, but leaves the motor running. Behind, the truck’s tire tracks cut a lonely path through the otherwise undisturbed snow that covers the road; ahead, there is only forest. A few curious wîskicâk — grey jays — flit over to examine their visitors with a curious chatter.

“It’s the end of the road,” Lawrenchuk announces with a puckish grin.

He means it literally. This dead-end strip of road is the furthest north you can drive in Manitoba and still be connected to the far end of the province. Turn around, and you will pass the brand-new Keewatinohk Converter Station, where Bipole III begins, trace the edge of the Sundance work camp, and then turn back onto Cree land, in Bird.

At 60, Lawrenchuk has travelled a long road to bring him back here. He grew up on this land, raised by grandparents who worked the traplines and somehow kept him out of residential school. So he spoke only Cree until he was old enough to start school in Gillam, where he mingled with everyone, played hockey, jammed in a rock band.

In 1982, Lawrenchuk left Fox Lake, for what he thought then would be forever. He ached to escape the dysfunction that swirled around the community, the wreckage Hydro had left. So he enrolled as a psychology student at the University of Manitoba and, in a bid to get over a crippling shyness, joined the student-run Black Hole Theatre.

Through acting, he found his passion, and it took him all over the world. He moved to England, where he performed Shakespeare and trained at the London Theatre School’s post-graduate program; he marvelled at how Europeans reacted to the fact of his being a First Nations person. More often than not, they were fascinated.

“I didn’t know that Indians were supposed to be treated any other way than we were being treated until I left Canada,” Lawrenchuk says, as he guides the truck down the road to one of the Hydro work camps. “When I left Canada and went to where I was going, they loved me. They wanted to take me out for supper.”

Today, he is still a playwright and actor; he founded an Indigenous Shakespearean troupe and recently had a role in the acclaimed 2017 feature Indian Horse. But in 1998, Lawrenchuk’s life took another sharp turn, when he got an unexpected call: Fox Lake wanted him to come home, this time as the new chief.

The job, he soon learned, was brutally draining. He travelled all over Canada, meeting with ministers and government officials; at night, he would slump in his hotel room, frustrated by the lack of action to improve the lives of Indigenous people. He even travelled to Geneva once, to speak about those struggles at the United Nations.

“To my surprise,” he says with a dry smile, “they didn’t give a shit either.”

As he drives, he gestures to the road outside, the one linking Fox Lake Cree Nation to the Hydro camps. When Lawrenchuk first moved back to the area, he says, you could feel the tension on the road. It was almost palpable, pressing down on the space between the trees, an invisible spectre born of distrust and frustration.

That started to change, he continues, right after the 2016 blockade.

Almost three years later, the memory of the blockade is still fresh in Fox Lake. Neckoway calls it “the best thing that ever happened” to make Hydro listen to what Fox Lake had to say. When McLeod thinks about it, a smile touches the corner of her lips: it was a “big turning point” for herself as a person, she says, and for the community, too.

“It was never about the money and compensation,” she says. “It was just for our voice to be heard after so long.”

It started with a casual act of destruction. There was a spot in the bush near the Radisson Converter Station, a short distance from Gillam, where Fox Lakers had gathered to hold a ceremony. They raised prayer flags on the spot, and ties of sacred tobacco, and made an agreement with Hydro to keep the area pristine.

One day, they went to check on the area and found it in tatters, razed by heavy equipment. The trees were gone, and the prayer flags and tobacco lay scattered on the ground. For many, it was the last straw; they’d braced themselves against Hydro’s encroachment for decades. Now, they were ready to stand their ground.

“Some of us got really concerned,” Neckoway says. “We’d just had a ceremony there. What the hell happened? Then you see this. And that’s when we started talking about different things. A lot of Fox Lake people started getting angry about what happened. ‘They’re doing this to us again.’ The disrespect, a lack of communication.’”

The community jostled for more decisive action. In Gillam, Chief Spence went to meet with two of Fox Lake’s senior-most elders, including Mayham. They didn’t quite come out and tell him what to do, Spence says, but in separate discussions each said nearly the same thing: “if you do nothing, then it will happen again.”

So they acted. They struck a plan to raise a blockade at the corner of Provincial Road 290 at the junction to the Bird reserve, blocking the way to and from some of Hydro’s key locations. Except for emergencies, they vowed, no traffic would pass until Manitoba Hydro had come to meet with Fox Lake, and hear its concerns.

Today, Spence remembers the scene, clear as the day it happened. It was a Thursday in mid-May, and a fresh layer of snow blanketed the land. Fox Lakers filled the intersection, where the community’s carpenters built a small shelter. They built a fire, and hunkered down for what they thought could be a long wait.

The day was not without humour: because of the language barrier, a group of Fox Lake’s elders, many of whom live in Gillam, went to the wrong intersection. Seeing no blockade, they grumbled for awhile about how young people today couldn’t get up in the morning for anything; the mixup was eventually rectified, to some laughter.

The chief’s phone rang. Kelvin Shepherd, then the CEO of Hydro, said he would come out to meet them. “We’ll be waiting,” the chief replied. The next day, Shepherd flew up to Gillam. And he walked into the wooden shelter at the intersection, accompanied by an assistant, and listened to what Fox Lake’s elders and members had to say.

“He was brave,” Neckoway says, with a chuckle.

That day, they hammered out a landmark agreement that would change Hydro’s relationship with Fox Lake forever.

Under the new deal, Hydro would explore opening a training centre, so northern youths could build their skills without leaving home. It would fund two key positions: one is McLeod’s job, as Harmonized Gillam Development Co-ordinator. The other job, now held by Lawrenchuk, is a relationship manager, a one-stop liaison between Hydro and Fox Lake.

Almost overnight, the mood in Fox Lake began to change. The tension Lawrenchuk once felt over the road seemed to dissipate. The communication between Hydro and the band began to improve, and that had ripple effects across the community. There was opportunity now, that they hadn’t always been able to see before.

The two sides grew closer. Today, Hydro and Fox Lake meet roughly every four to eight weeks through the harmonized Gillam development program, and the relationship is “fundamentally different” than it was even four years ago, says Vicky Cole, Hydro’s director of northern Indigenous relations, who has worked with Fox Lake since 2005. She knew things had changed when, in 2018, Fox Lake leadership went to Sioux Lookout to learn more about innovative social healing work there, and invited Manitoba Hydro’s staff to come with them.

“I thought, ‘this is great. We’ve really come a long way,’” Cole says. “We’re all collectively thinking about the problem together, and that is such a fundamental change… There are always things we might not see 100 per cent eye-to-eye on, but the relationship’s at a place where we can have a conversation about it and move forward.”

That feeling was echoed in Fox Lake.

“You have some good people working out there trying to make good changes with the Fox Lake Cree and Hydro,” Neckoway says. “And we have some Fox Lake people working for Hydro, a lot moreso now. That’s some of the good changes, because before there was none. We have a better working relationship.”

It was more than that. In a way, the blockade was Fox Lake’s statement of resilience. Fifty years since Hydro first crashed over their land, they had at last taken their spot at the table. A community of just 1,200 people had stood up to a Crown corporation that would take in more than $2.3 billion in revenue in 2018, asking to be heard, and they’d won.

“I think that was one of the most important events in our community,” Chief Spence says. “It demonstrated that we are taking the ownership of the situation. Because they lived with so much of the letdowns, the frustrations, and that’s what I’ve heard from all the band meetings leading up to it.

“In social work it’s called a cathartic experience, because you go through all the emotions,” he continues. “They were happy we’d made some movement. When anyone participates in social action, and they put their full heart into it, and they see some of the results. We still have to work at it, but I don’t think they’ll ever forget that.”

He pauses. “I won’t forget it, anyway.”

A stronger community

It is a sunny Friday morning in Fox Lake Cree Nation. Underneath the soaring ceiling of the band office’s conference room, maps are spread out on tables. A team of elders from Fox Lake and York Factory First Nation are meeting with Parks Canada officials, the start of a project to restore Cree place names to features in Wapusk National Park.

“First Nations showed all the non-native people this area,” Lena Spence-Hanson says, chatting in her office down the hall. “But we’re an oral people, right? We never wrote things down. When Europeans came, they wrote everything down. So it looks like they found these areas, when in fact it was my great-grandfather who showed them.”

Spence-Hanson is animated as she talks, recalling her time growing up in Gillam. In a way, her path mirrored that of the community itself. It wasn’t until her 30s, she says, that she began understanding her identity as a Cree woman. Today, she is a drummer, and though she cannot speak fluent Cree, she can sing in the language.

“I couldn’t even accept who I was because of how I was raised and what I was told,” she says, and her eyes shine with everything that means. “But now as an adult, and learning who I am as a Cree person, learning about my true history, that gives me my oomph to say, ‘OK, I have something to say, too. Now it’s your turn to listen to us.’”

What does that look like? Spence-Hanson reaches for a newspaper on her desk. She was just reading a story that morning, she says, about how two young women arrested in The Pas after posting racial slurs on Facebook were held accountable in an Indigenous mediation circle. That’s the kind of justice she longs for, to help heal Fox Lake.

“The non-native people need to be face-to-face with us, because when you’re face-to-face with somebody… I know you can feel how I can feel,” she says. “And I think that’s important, for non-native people to feel how we felt. Because you’re not going to know unless you’ve been through it. That’s how we are. That’s how we learn.”

For Neckoway and others in the community, the education continues.

“Knowing who I am, spirituality… that helped me move on in a good way,” she says. “Even though I do have some of that anger that comes back to me once in a while because of the past, it helps me move on in a good way, thinking, ‘OK, that’s the way it is; how can I do better today with this? How can I change that?’

“So helping out with the way you treat the kids in the community, the youth, the elders… treating each other in a respectful way, with kindness and love, that’s the change I see happening,” she says. “Without that, you can’t really move on. If you’re stuck in the negative all the time, it doesn’t really change anything. You just stay where you’re at.”

And Fox Lake is moving forward. For years, the band has operated a joint partnership with food-service giant Sodexo, running catering for the Hydro camps. The effort employs many Fox Lake members, and profits from the venture helped fund the whimsically designed Fox Lake School, where about 26 K-8 students attend classes.

The railroad to Churchill is running again, now owned by a consortium of First Nations that includes Fox Lake. In a way, taking control of the railroad is also part of reconnecting with who they were before Hydro threw everything into chaos; some of the workers who were laid off when the railroad shut down are talking about going back.

And they still know how to live on the land, as they’ve always done. On the school’s bulletin board, there are photos of one of Mike Lawrenchuk’s sons, a trapper, showing young students how to skin a wolf. An elder visits to teach the kids how to do traditional beading and a desk in one of the classrooms blooms with their efforts.

The community runs goose camps for youths and moose-hunting camps. The knowledge of mîno-pimâtisiwin is coming back, and the younger generations seem to be thriving on its lessons. In 2018, more than half of the Grade 12 graduating class at Gillam School were Fox Lake youths, and many are going on to higher education.

That’s what matters in all of this, McLeod says. It’s the next generation. The struggles of the past, the blockade, the land they are still fighting to recover; all of that work has been to lay out a future where Fox Lake’s youth can blossom.

“I can be all against Hydro for everything that they’ve done, but I can’t do anything about the past,” McLeod says. “To be able to live with it and adapt to it, that’s where I’m at right now. If I could take it all away, I would, to go back to the old ways. But.. it’s our younger generation, the smaller kids, and our kids, and their kids and their grandkids.”

And the resilience of the Fox Lake Cree has changed Manitoba Hydro, too. The community had long told Hydro about the social impacts of development there; those lessons, Cole says, helped shape some features of the Keeyask and Keewatinohk developments that were designed to mitigate not just the environmental impacts, but the social ones, too.

“I think historically… a lot of the emphasis publicly has been on the environmental impact of hydroelectric development, and what that means for traditional pursuits, and what that means for Aboriginal and treaty rights,” Cole says. “One of the lessons of working with the community of Fox Lake, which they brought to the forefront in the mid- to late-’90s through discussions with Manitoba Hydro, was the real impact that an influx of workers can have on a population, and what that looks like and what that feels like if you’re the community experiencing it.

“I do think Hydro has changed quite significantly in terms of its willingness to address those issues,” she adds later, noting that some of the most meaningful acts on this end can be the most simple: ensuring a community is linked to counselling resources, for instance.

There is still work to be done. McLeod’s focus now, she says, is trying to help her people heal, to restore families that have been splintered by generational trauma. It is a long road, but with each year that passes, the community grows a little stronger.

“The Fox Lake of yesterday is not the Fox Lake of today,” Wavey says. “I look forward to seeing all those up-and-coming bright young minds taking over, putting us aside and letting us rest. They don’t focus on the damage. They focus on rebuilding.”

That’s always been the story of the Fox Lake Cree, as old as time and always renewing. They’ve survived on this land for countless generations. They adapted to the fur trade, and the railroad, and the Hydro developments that landed on top of them. That last great shock could have destroyed them, and yet still they are standing.

They will not forget. Everything that has happened is part of who they are. Good and bad. Hope and trauma. They have kept their elders’ memories safe, and the stories will be passed down through generations. But so will the lessons they learned along the way, hard-won and vivid, about how they clawed their way back.

“One of the things we learned a long time ago is that we’ve got to preserve our history,” Lloyd Kirkness says. “We’ve got to understand where we come from. We’ve got to understand what happened, to let our young people know who we are and what happened here, so they’ll understand how to deal when something like this happens again.”

Because change will come again to Fox Lake. When Hydro finishes the Keeyask project in 2021, it will pull most of its workers out of the region. But some believe there are mineral deposits somewhere outside of Gillam. Someday, another influx of workers and camps could start streaming up from the south. This time, if it happens, Fox Lake will be ready.

“You’ve got to make sure that we are participants, because this is our homeland,” Kirkness says. “We’ve got to understand how it’s going to benefit us as First Nations people, and how’s it going to benefit other First Nations in the area. They can’t just come and do what they want and leave. The time for that is gone.”

People and land. Land and people. The ways they belong to and take care of each other, indivisible: that is what this has always been about. And if Winnipeggers should know anything about what happened in Fox Lake, Spence-Hanson says, and about the power that lights up their days, then it is the truth of that statement.

“Fox Lake is not just the name of a place,” she says. “Fox Lake is who we are. Fox Lake is what we are. We are part of this earth, this Cree country. Our ancestors are buried, our blood is buried in this area. We are a people of the land, we love everything about it, and like our chief said once, we’ll live and die here.

“We’re not going anywhere,” she adds. “And we still haven’t gone anywhere.”

The afternoon light is growing long. Outside the band office, in the withering cold, the air bites cheeks and earlobes and fingers. Spence-Hanson wriggles into her thick wolf-fur hat and sealskin mittens. She pauses to say goodbye to her visitors and, with a flourish, strikes off for the 40-minute drive home to Gillam.

“Êkosi,” she calls out, and raises both hands in parting.

Then she grins, and the chime of her laughter is carried away by the wind, until the only sounds left are the whispers of trees, the crunch of boots on old snow, and a quietude that city ears strain to know. A song of the North, and all the stories that flow through it, bubbling up from the groundspring of some timeless long-ago.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.