Public transit, private trauma Drivers describe frequent verbal, physical abuse on the road and then being thrown under the bus by insensitive colleagues, supervisors

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/03/2019 (2466 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

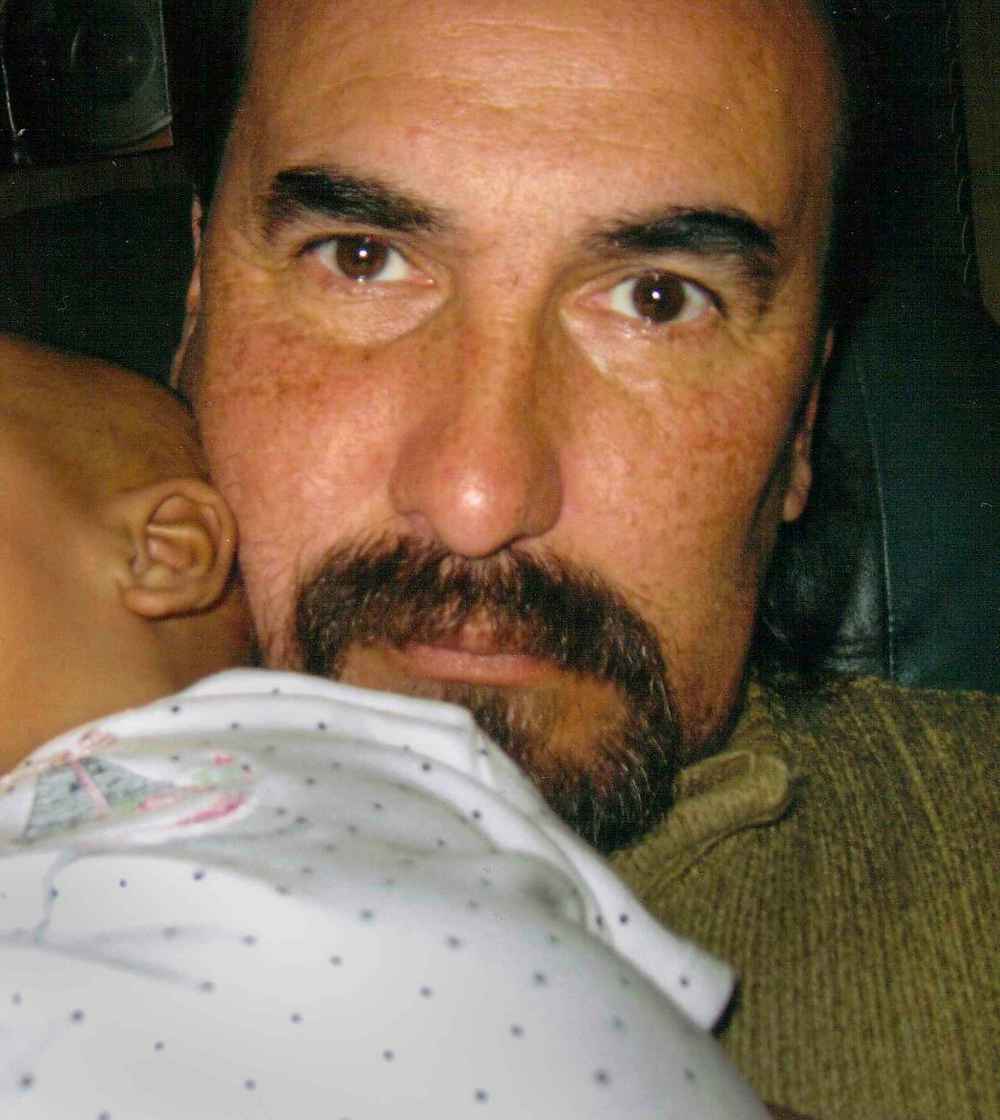

Tasting human feces is something Brian Lennox could have done without.

It was just past midnight, in the fall of 2003, and Lennox — a career bus driver then in his 25th year with Winnipeg Transit — was doing his best to stay alert behind the wheel.

The bus was relatively empty, with a few passengers spread out behind him. He pulled up to Stop 40460, at Talbot Avenue and Allan Street, and saw two boys waiting for his arrival.

At night, Lennox was always nervous, the result of guns pulled and knives drawn on the “dead man’s shifts” he routinely drew.

From his seat, he looked at the boys, who seemed innocent enough, and swung the door open. “Good evening,” he recalls saying. Then, another boy — in his late teens, from the looks of him — hopped out, and pelted Lennox with plastic bag after plastic bag brimming with feces, vomit and urine. “I never saw it coming,” Lennox said.

It went into his eyes and up his nose, filled his ears and flooded his mouth as he screamed out of pain and fear for his life. He thought it had been acid, his eyes burned so badly.

The driver’s seat and the next two rows were drenched, and Lennox’s tears came fast. “I was blind until the ambulance came,” Lennox, 65, recalled recently.

One of his superiors arrived to assess the situation, and then drove Lennox — still shaking, still crying — to his house.

When he returned to work a few days later, operators and supervisors asked him about what had happened. When Lennox told them, many laughed, he said, mocking him for crying and screaming, calling him a “wuss,” a “pussy” and other, even more vulgar, terms.

“They said it could never happen to them, and that it happened to me because I was weak, short,” said Lennox, who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of his time as an operator. “But when you’re driving, these things can happen to anyone.”

“They said it could never happen to them, and that it happened to me because I was weak, short. But when you’re driving, these things can happen to anyone.”–Brian Lennox

Transit drivers, Lennox says, must often contend with schedules that are near-impossible to keep, deal with piecemeal shifts that can throw their work-life balance into disarray, work through significant back, neck and foot pain, work without breaks — bathroom or otherwise — and keep the wheels rolling, all while trying to get hundreds of people in a hurry to where they need to go.

Those are challenges a lot of drivers expect, and accept, from the moment they first don the uniform.

But none of those things were dealbreakers for Lennox; what made the job so untenable for him was “machismo gone wild,” an environment of toxic masculinity that expected drivers to “man up” and keep driving.

When he had a gun pulled on him and was punched while driving in 1985, Lennox said, a supervisor — rather than asking if he was all right —asked him what he’d done to deserve it, a rejoinder Lennox heard dozens of times throughout his career.

“We were always at fault,” said George Morrison, who retired in 2013 after 30 years behind the wheel.

“Management wouldn’t trust us as far as they could throw us. It’s almost like bus drivers are an expense they needed to get rid of.”

Lennox last drove a bus in 2010.

“It took me 20 years to realize that (my situation) wasn’t isolated,” he said. “It was part of a culture of policies and practices that implicitly — if not explicitly — said it’s all right to treat drivers with contempt, because management itself held us in contempt.”

The Free Press spoke to several other operators, both retired and current (who can’t be identified, in accordance with their employee agreements). Each one said disputes with passengers represented only a tiny fraction of their on-the-job stress; the major contributing factor was a management team that, as Morrison suggested, viewed them as expendable, and as Lennox alleges, treated them with contempt. Each one also suggested operators feel pressure not to report incidents to their supervisors for fear of reprimand from the higher-ups.

“Morale has never been lower,” one veteran driver said.

Former operator Dennis Ballard quit in 2001 after three years on the road.

“I would say there was an atmosphere of bullying,” he said “(Supervisors) failed to provide a safe work environment.”

A Transit official paints a very different picture.

“We’ve always taken (operators’) safety very seriously,” said Randy Tonnellier, Winnipeg Transit’s manager of operations, a former driver who denied the existence of the toxic atmosphere the drivers implied, as well as any attempts to suppress incident reports.

“I would certainly say it can be a challenging job,” he added when asked what more could be done to improve the work environment. “I know that it’s not a job that’s for everyone, and that it’s not easy.

“You have to deal with a lot of competing demands at once, from driving a large vehicle through construction and challenging road conditions, to dealing with passengers at times when they might be really challenging to deal with. Plus, you’re operating on a schedule,” he said, pausing.

“It’s a very challenging job.”

● ● ●

Adam Chouinard became a driver for reasons that are pretty easy to understand. He was 25, starting a family and, by his own admission, was poorly educated; a city job — with the associated benefits and potential for an increase in pay, along with a solid pension — seemed ideal.

“It was the perfect job,” said Chouinard, who planned to retire at 55. “At least, that’s how it seemed.”

About a year into his career, in 2007, he was driving past Confusion Corner in his Honda Civic on the way back from a break in the middle of a “two-piece” — a split shift many drivers are routinely scheduled to do. The next thing he knew, he crashed into an oncoming van just before the latter half of his shift was to begin.

The car was badly damaged.

“I was sitting there shaking like no tomorrow,” he recalled. “I call in, tell them what happened, and (the supervisor) said, ‘You better hurry back.’”

A few months earlier, Chouinard’s pregnant wife was in intensive care, on life-support. He called work to explain the situation, and his boss, he said, asked him to come back in to work. If he didn’t, he’d be marked for missing a shift.

“No sympathy whatsoever,” he said.

At first, he reported incidents — people whipping pennies at him, spitting on him — to management, but got no response. In 2007, he asked a group of rambunctious young men to calm down or get off the bus; one pulled a gun on him. He was reprimanded for asking them to get off, and no support was offered to help him deal with the trauma.

“We were always seen as aggressors, never the victim,” Chouinard said. “After the gun, I thought, ‘What’s the point in reporting?’ Either I get in trouble, or nothing’s going to happen.

“Transit spends three or four months training you. The rest is spent trying to get rid of you, it seems.”

“We were always seen as aggressors, never the victim. After the gun, I thought, ‘What’s the point in reporting?’ Either I get in trouble, or nothing’s going to happen.”–Adam Chouinard

As of March 1, the average length of service among the 1,423 current Winnipeg Transit drivers, excluding those in training, is just under 11 years. Over the past several years, Transit has made efforts to increase its hiring to keep up with growing demand on the service, Tonnellier said.

In 2017, 98 operators were hired, followed by 164 last year. But over the last four years, 17 per cent drivers have voluntarily left the job within their first year.

Chouinard was gone after three.

His last shift ended before it started, when he got chest pains as a bus pulled up to his stop near Confusion Corner. His blood pressure was sky-high, and an ambulance raced him to the hospital with what was later determined to be a panic attack.

“Not once did a supervisor come see me,” he said. “They called and asked me to make sure I was available for the next day’s shift.”

Chouinard now works as an RV technician. He said if he hadn’t left Transit, he’d likely be debilitated from the constant stress.

According to the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba, between 2014 and 2018, there were 27 claims by bus operators under the category of “exposure to traumatic or stressful events,” all of which were accepted.

Chouinard said he believes the number of Transit workers who could reasonably make such claims is much higher, but most keep their head down and keep driving.

Chantale Garand, 29, quit Transit last fall after six years as an operator, citing PTSD and anxiety from her interactions with management as a key reason for her departure. Garand said she experienced constant intimidation from higher-ups, including immediate supervisors, who she said constantly used intimidation tactics to assert their control.

Once, she got off the bus to use a bathroom at a Tim Hortons restaurant and a passenger filed a complaint.

Transit said it encourages drivers to take breaks when needed, but Garand said she received a visit from a supervisor, who reminded her of the importance of staying on schedule.

“When you’re consistently reminded of the schedule (in situations like that) it tells you: don’t do that,” she said.

Garand, an Indigenous woman who identifies as queer, said she also experienced consistent harassment behind the wheel, including people using racist and homophobic slurs when addressing her.

When she told a supervisor that she’d experienced personal attacks, she says the response she got was that the homophobic behaviour she’d reported “didn’t exist anymore.”

“When your immediate supervisor is telling you that what you’re experiencing — something he’ll never experience — doesn’t exist, that told me what should be my source of help had become the opposite,” she said.

“If I can’t be queer at a government job in this day and age, where can I be? It shouldn’t be more stressful after an assault to deal with Transit than the assault itself.”

“It shouldn’t be more stressful after an assault to deal with Transit than the assault itself.”–Chantale Garand

Another time, a passenger who behaved offensively in the past — telling Garand he was going to “rape her mother” — boarded her bus on Ellice Avenue. When she called her supervisor to tell them she felt unsafe, she was told to carry on “as best as she could.”

She had a panic attack and felt unsafe with 40 other passengers in aboard. At a meeting with her supervisors, Garand said she was criticized for her attitude on the phone and wasn’t asked whether she was OK. She took stress leave shortly after, and never went back.

Dennis Ballard, an Indigenous driver who quit in 2001, said he didn’t encounter racism from passengers, but did from co-workers and higher-ups.

“When you call them out on it, they said, ‘What? Can’t you take a joke?’ But they never meant it that way. It was spiteful, and it was never funny.

“If you hold these stereotypical beliefs, what kind of service can you even provide?” he asked.

Transit, Tonnellier said, has worked to maintain diversity within its ranks. About 2.6 per cent of all drivers identify as disabled, nine per cent as Indigenous, and 30 per cent as a member of a visible minority. At the management level, three of nine managers and three of five operations supervisors are women.

Since she left the job in November, Garand has been an outspoken critic of Transit in media and in conversations with other drivers who share her concerns. Ultimately, she said, she felt as though she was considered disposable by management and she alleged that incident reports related to assaults — which have averaged 49.8 per year over the last five years — have been suppressed, a concern shared by the Amalgamated Transit Union’s local president, Aleem Chaudhary.

And Garand was far from the only operator who told the Free Press statistics are suppressed, a notion Transit rejected out of hand.

“Absolutely not,” the spokesperson wrote. “Operators are taught during their initial training that they are to report all incidents. Their ongoing training stresses the importance of this, as well.”

Transit has issued several reminders to staff over the past two years to report assaults, the spokesperson said.

“We take any reported assault on any of our drivers seriously, and we get them all the resources we need,” said Tonnellier. “We try to create policies that provide a lot of leeway and encourage people to report incidents, and to come forward with any issues with their schedules they might have or anything else they need help with.”

Transit has taken strides to improve workplace safety and to pay better attention to their employees’ mental well-being, he said. In 2017, the organization’s Transit Advisory Committee began meeting, and a safety campaign aimed at encouraging the reporting of undesirable behaviour began.

The next year, he said, Transit received funding approval from city council on expanded audio-video surveillance on board buses and added several new positions, including nine inspectors and three dedicated relief operators.

It also developed and implemented safety training for inspectors and ran a pilot training program delivered by the Main Street Project to help raise drivers’ awareness on mental health and homelessness, as well as a two-day training program with a focus on on-the-job challenges and mental health.

A 12-month rollout of operator shields just received budget approval from the city.

“I think as a nation, as a city, and as an employer, we’ve all broadened our understanding of what non-physical injuries can be,” said Tonnellier. “So I’m happy to see us move in a direction where we are proactively training employees.”

“I think it makes for a better workplace than when I started.”

Of course, for some drivers, including Garand, Chouinard and Lennox, it feels like too little, too late.

•••

There isn’t a bus driver in Winnipeg who doesn’t know what happened on Feb. 14, 2017.

Irvine Jubal Fraser, a veteran driver working a late-night route, got into a confrontation with a passenger who was drunk and sleeping in the back of his otherwise empty bus at the end of its line on the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry campus.

Fraser asked the man to leave, but he refused. After a heated exchange, during which the man was visibly distraught — as on-board camera footage showed — Fraser grabbed the man and pushed him out of the front doors.

The man taunted Fraser, telling him to come out and fight, before spitting in the driver’s face. Fraser got out of his seat, went outside and was attacked, suffering fatal stab wounds. He was the first Winnipeg Transit driver to be killed on the job.

The next day, and on the one-year anniversary of his death, Transit drivers flashed messages of mourning on their buses windshield signage: REST IN PEACE #521, referencing his badge number.

In January, Brian Kyle Thomas, 24, stood trial for the incident. He admitted to stabbing Fraser six times, but pleaded not guilty; his lawyers argued that he was acting in self-defence, that he was too intoxicated to have committed murder. Thomas was found guilty of second-degree murder.

Two weeks later, on the second anniversary of Fraser’s slaying, drivers planned to display the memorial messages again, but were shocked to find a management posting that asked them not to and telling them they could memorialize him on the city’s official day of mourning in April.

It caught most drivers, and the Amalgamated Transit Union’s local branch, off guard, though Transit released a statement saying it had informed the union of the directive in advance.

“It’s a kick when somebody’s down,” said Chaudhary.

Retired driver Bob Sawatzky wasn’t surprised.

“It’s almost as if they cannot walk away from a fight,” he said.

But the kindness of some Transit customers helped soften the blow with cards, cookies and hugs for drivers in a citizen-led Transit Appreciation Day, an effort that Kevin Sadowy and his sister Heather spearheaded.

“I think regardless of the industry, acts of appreciation or kindness are important,” said Sadowy, a daily rider. “It certainly is about Irvine Fraser, but it’s about the drivers who survived him, and bringing some brightness to their day.”

One current driver said the decision by Transit was an indication that whatever systems had been put into place to protect drivers, the organization was “not committed” to helping operators deal with Fraser’s death.

“The morale was already very low,” he said.

And Morrison, the retired driver agreed.

“This was like taking two steps backward,” he said.

•••

What haunts Brian Lennox most isn’t the time he stared down the barrel of a gun, or the time he had to throw away his human-waste-covered uniform. It’s that he has to relive the incidents, day after day.

Just talking about his experiences as a driver can set him back a week. Transit provided him with access to some resources under its employee assistance plan, including psychological help. He moved out to the country after he retired, and now spends his time in nature, far away from the bus routes that slowly ate away at him.

When Fraser was killed, Lennox felt a deep pain that hasn’t since subsided.

“Survivor’s guilt — you heard of it?” he asks, voice trembling.

When bus drivers are in training, they routinely ride along with more experienced operators, and when Fraser was starting out he rode with Lennox a few times.

“I knew Jubal,” he said.

Lennox, like many drivers in the wake of Fraser’s death, has had to contend with something he long denied: it could have been him, and on more than one occasion, death was a trigger-pull away.

One operator — a young father — recently had a drunk passenger scream at him from directly behind his seat, asking how long until the bus would arrive at Assiniboine Park.

“My attention was on the passengers boarding, so I asked him politely to move aside,” he said.

Then, the man screamed. “This is why you people get stabbed to death,” and asked the driver to leave his seat, telling him to “come outside and I’ll kick your ass.”

The driver said a senior Transit official told him that it wasn’t technically a direct threat.

He recounted this story at a downtown café in February, his young child bouncing on his knee. “What makes me more apprehensive about going to work isn’t that the risk is there, but rather how the risk is managed,” he said. “The response? There is no response.”

Garand said that when it came to driving remote, late routes — such as the one that Fraser was ending on the night he died — she was constantly fearful that none of the 50 trained Transit inspectors would be able to respond in time. Transit won’t say how many are on the street at a given time.

“Assaults are never going to be eliminated on Transit, and people know that, but you can reduce them significantly with how you do things,” she said.

And Transit is trying, Tonnellier said. The organization has worked to develop intervention strategies and programs to help prepare its drivers for what they may face on the road, including passengers in distress.

It’s a step in the right direction, but drivers such as Lennox — and he insists there are more who suffer from PTSD than those who admit it — are already serving life sentences.

“It wrecked me,” said Chouinard. “It’s such a physically and mentally tough job. It takes a real special person to handle it.”

Lennox said he hopes current drivers hear his story, see his willingness to be vulnerable and start to stand up for their own happiness and well-being.

He became a driver because he wanted to get people where they wanted to go. Garand signed up because she aspired to move up within the city, and to make a difference for other employees. Chouinard wanted to secure his young family’s future.

Drivers usually sign up for all the right reasons, Lennox said.

But the nightmares, flashbacks, guns, pain, spitting, screaming, fear, anger, tears, alleged bullying and mistreatment?

They didn’t sign up for that.

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.