Survival of the weakest Spanish flu terrorized the world a century ago. Today, researchers understand why it was so deadly, and are working to stop another pandemic

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/02/2019 (2489 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

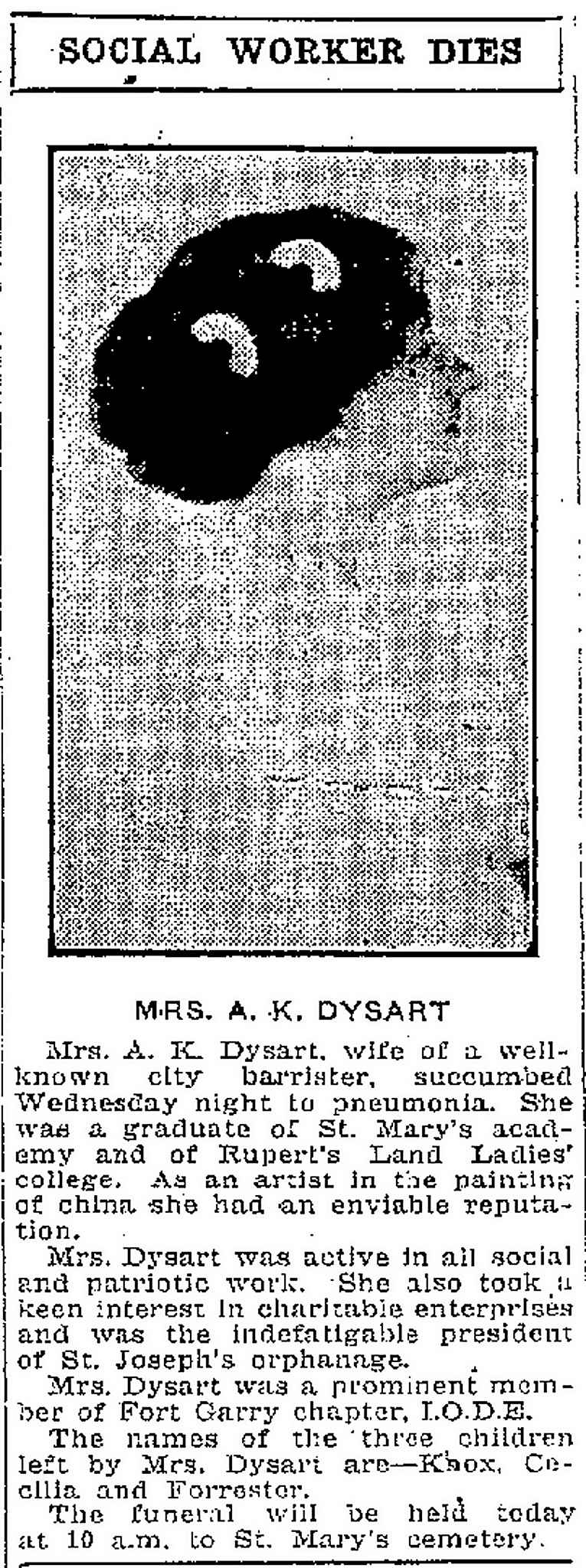

One of the first victims of the Spanish flu that terrorized Manitoba a century ago was Claire Dysart, a wealthy philanthropist living in Winnipeg’s Assiniboia district.

Dysart was the type of young woman who got written up in the society pages. The Winnipeg Free Press wrote about a party thrown in her honour a decade earlier, when she was still single, to welcome her back from a trip to the West Coast. That wasn’t the kind of press most young women could expect.

Claire married well, to A. K. Dysart, a prominent barrister named to the King’s Counsel, an honour bestowed upon exceptional lawyers. She was president of the St. Joseph’s Orphanage. She died on Oct. 10, 1918. She was just 31.

Her death marked an early theme with the worldwide pandemic. Not only did the Spanish flu kill and kill often, it didn’t care who you were, rich or poor, young or old.

In fact, the prosperous homes along the Assiniboine River were among the first ones menaced by the deadly virus. It wasn’t until a week later, on Oct. 17, that the first case of Spanish flu was reported in the North End, one of the poorest neighbourhoods and one where the virus would prosper due to the overcrowding of immigrant families.

The Spanish flu was barely out of the crib when it claimed Dysart. The first wave of the influenza had ripped through war-torn Europe in late spring. Some historians theorize it hastened the end of the First World War.

Now it was autumn and the second wave was coming. Manitobans heard reports of the deadly flu but it seemed to be missing them and some local health authorities were even claiming victory over the disease.

Besides, it was just a flu. Sure, the very young and very old were vulnerable, along with those who had medical conditions, but to 90 per cent of the population, it was just a nuisance. No one was accustomed then, just as no one is today, to thinking that if you came down with the flu there was a good chance you would die.

But as Spanish flu spread, a soreness in your throat or sniffly nose was suddenly a matter of life or death. It meant you might only have three more days to live.

Then it was reported 23 men on a troop train that had stopped in Winnipeg on Sept. 30 had contracted the Spanish flu virus. The soldiers had been on their way to the West Coast. Fifteen of the men were so ill they had to be carried off the train on stretchers. They were quarantined at the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) military hospital in Tuxedo, a home for convalescing soldiers.

The newspapers were silent for a few days but then it was reported two of the soldiers died on Oct. 6 and at least two more were gravely ill (and eventually died).

While that rang alarm bells, at least those men had been quarantined thereby keeping the general population safe. As a Free Press subheadline stated: Physicians say situation well in hand.

But the virus was opportunistic and had already snuck out the IODE hospital doors and begun wandering Winnipeg’s roads. The newspapers next reported two people on Garfield Street in the West End had contracted Spanish flu, as had a person on Guelph Street, and an orderly at the IODE.

Not everyone with Spanish flu was fated to die but a relatively high percentage would. Within days of Dysart’s death, it claimed another prominent Winnipeg citizen. On Oct. 14, William H. Escott, described by the Free Press as one of Winnipeg’s best-known businessmen, succumbed.

He’d only been sick for a few days. The typical length of the flu was about three days but some people died after a week and some died within hours. People who died in a week likely died from pneumonia. The flu would severely compromise a person’s health, opening the door for pneumonia to move in, and it was before the invention of antibiotics.

Some people died extraordinarily quickly. There were reported cases where individuals went to sleep apparently healthy and never woke up. One Winnipeg case that made the news claimed a young man in the prime of life, while visiting his mother, died within a matter of hours.

“The treachery of the malady is demonstrated in the death of Henry Drummond, 467 Flora Avenue. Three hours after the first symptom showed, he was dead,” the Free Press reported on Oct. 23.

“The treachery of the malady is demonstrated in the death of Henry Drummond, 467 Flora Avenue. Three hours after the first symptom showed, he was dead.” –Winnipeg Free Press, Oct. 23, 1918

Escott’s business, W. H. Escott Ltd., a grocery brokerage that bought food from manufacturers and sold it to wholesalers and retailers, still operates today in Winnipeg’s Exchange District, in the old Eatons Catalogue Building at Alexander Avenue and Lily Street. The family is no longer involved. Following Escott’s death, his wife ran it for a couple of years and then sold it.

The number of deaths kept rising and no one could say how long the pandemic would last but the expectation was that it would be brief, maybe three weeks.

Even in those early days, newspapers ran optimistic headlines, claiming the pandemic was on the run, based on information from health authorities. Such claims were made again and again over the next three months, only to be retracted days later by a daily death count that had reached new heights.

***

It seems odd that of all the calamities in our own and the world’s history, the Spanish flu is not better remembered.

Perhaps that’s because it coincided with the end of the First World War. We know Armistice Day, but we hardly know about the worst pandemic in humankind’s history. In Winnipeg, Spanish flu was sandwiched between the war’s end and the General Strike of 1919.

Perhaps the reason is it came and went so quickly. It arrived at the start of October and most of its victims were claimed before New Year’s. Another wave arrived in 1919 around March. It was lethal again, but for a shorter duration.

It disappeared and never came back, not yet, anyway. It’s why world health authorities are so jittery. They’re constantly on the lookout for the next pandemic and making sure protocols are in place should it come.

Meanwhile, the word “plague” became part of the lexicon of the Free Press, used interchangeably with “epidemic,” and no one corrected it. It was a reference to the Black Death, the bubonic plague of medieval times.

The Spanish flu was not the plague but it proved to be a modern-day equivalent. More people died from Spanish flu in a 15-month period than died from the Black Death from 1347 to 1351.

One-third of the world’s population contracted Spanish flu, and at least 50 million are estimated to have died. About three-quarters of the deaths occurred within a four-month span at the end of 1918.

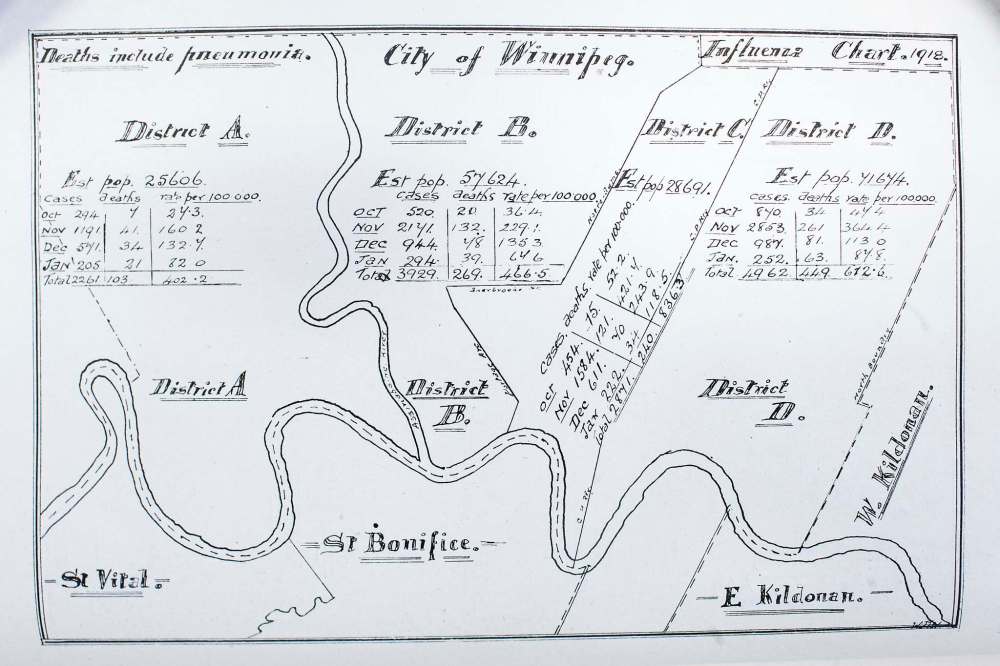

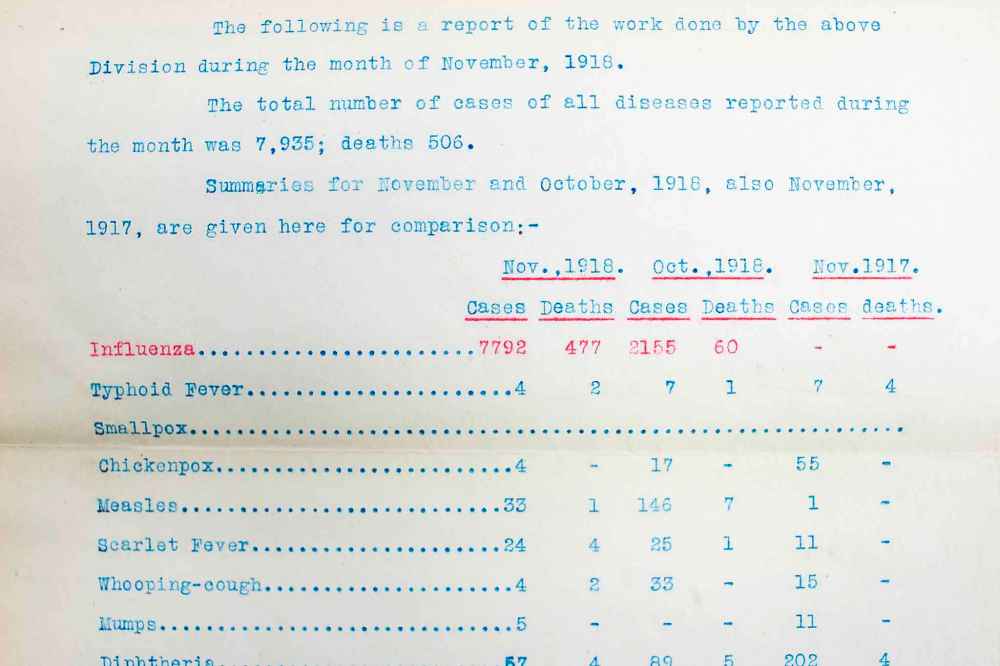

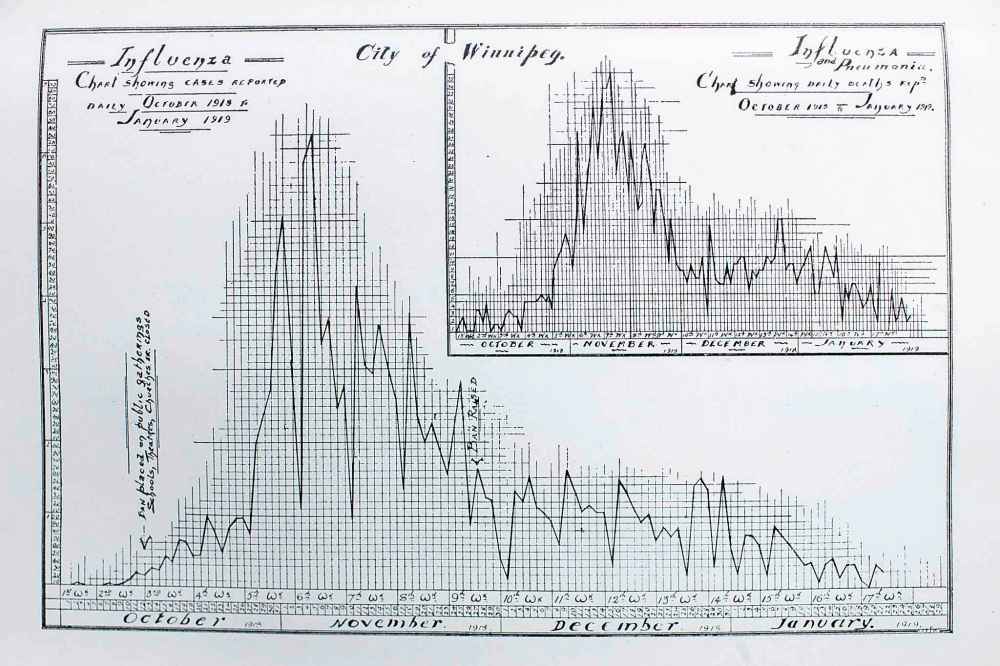

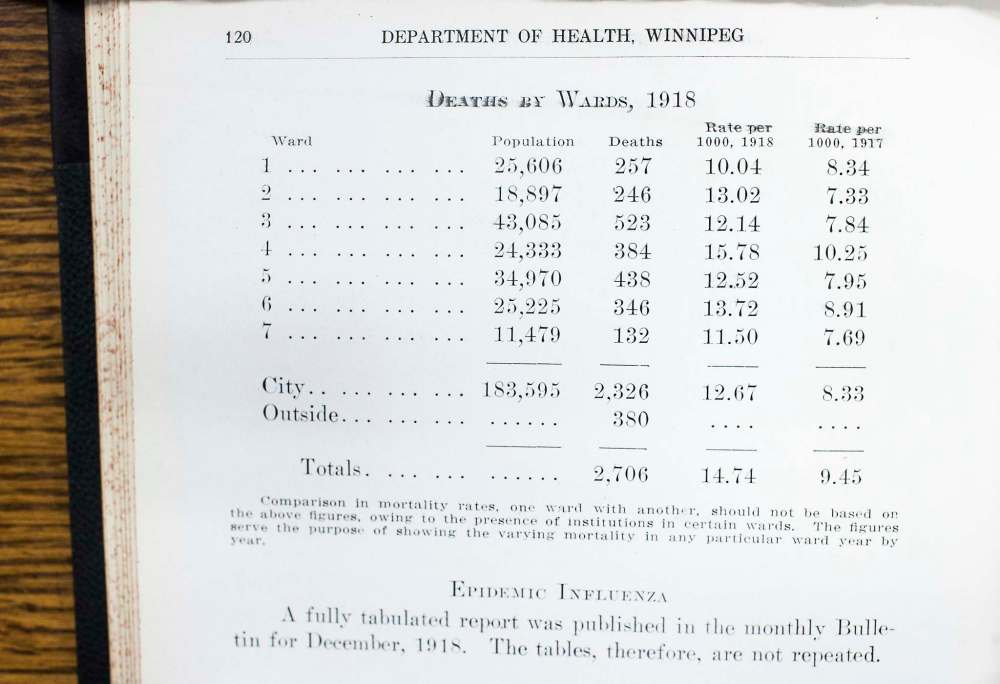

It swept through Winnipeg and killed at least 1,216 people — those deaths registered as a result of Spanish flu. The city’s population at the time was just 183,595.

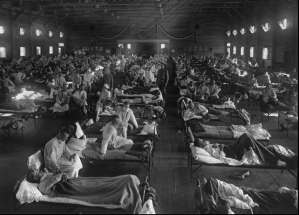

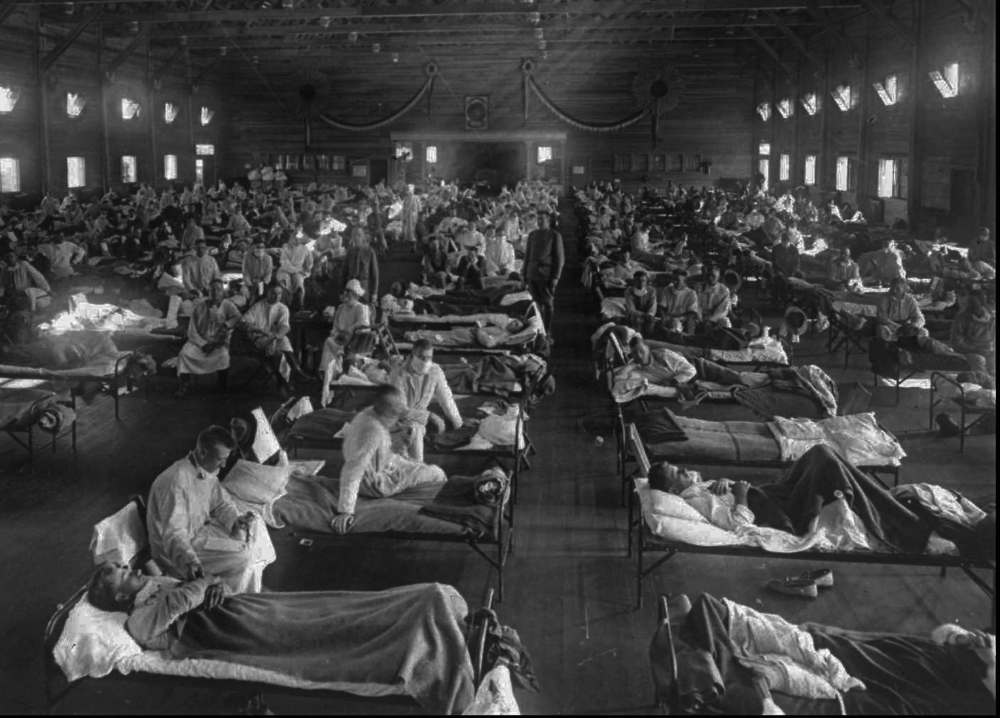

Winnipeg was in the throes of the pandemic by mid-October that year. The city’s health care services were soon overrun. They ran out of hospitals and they ran out of nurses. Hospitals filled up and had to turn away patients. Health authorities scrambled to find space to accommodate the sick.

The Winnipeg General and King George hospitals filled up with flu patients, so space was opened up at the North Winnipeg Hospital. The St. Boniface, Grace and Victoria hospitals also set up units to take in flu victims, keeping them separate from other patients. The Children’s Hospital, then on Aberdeen Avenue, took in stricken children but also children whose parents were too sick to care for them or who had died.

It still wasn’t enough. They had to convert buildings into hospitals. One was supposed to be downtown at the former Forrester Building at Graham Avenue and Fort Street, where the entrance to Winnipeg Square is now.

Owner Charles Forrester offered the building rent-free in memory of his sister, one of the Spanish flu’s first victims — Claire Dysart. It was to be named the Claire Forrester-Dysart Emergency Hospital and furnished with 500 to 600 beds. Since no other references could be found in the Free Press archives, it may well be that the plans were not carried out.

There were other buildings, however. St. John’s College was turned into a temporary hospital. Another 200 beds were opened at a building called Old Coffee House at Logan Avenue and Main Street. The La Salle Hotel in Elmwood was also converted into a flu hospital.

It wasn’t just Winnipeg, of course. In the small northwestern Ontario town of Sioux Lookout, 200 people, almost the entire town at the time, were reported stricken with Spanish flu and its only doctor had died from it.

Almost immediately, Winnipeg ran out of nurses to handle the pandemic. Calls went out for volunteers, almost entirely women back then because they were regarded as caregivers.

Women volunteered from all economic backgrounds. The upper and middle-class volunteers received the most press coverage but women within immigrant communities served within their own ethnic and religious groups.

Men volunteered, too, but in a much smaller capacity and typically served as drivers, manoeuvring makeshift ambulances to transport the volunteer nurses from site to site.

But it was the city’s women who entered the lion’s den. They went into people’s homes. Many volunteer nurses would pay the supreme price.

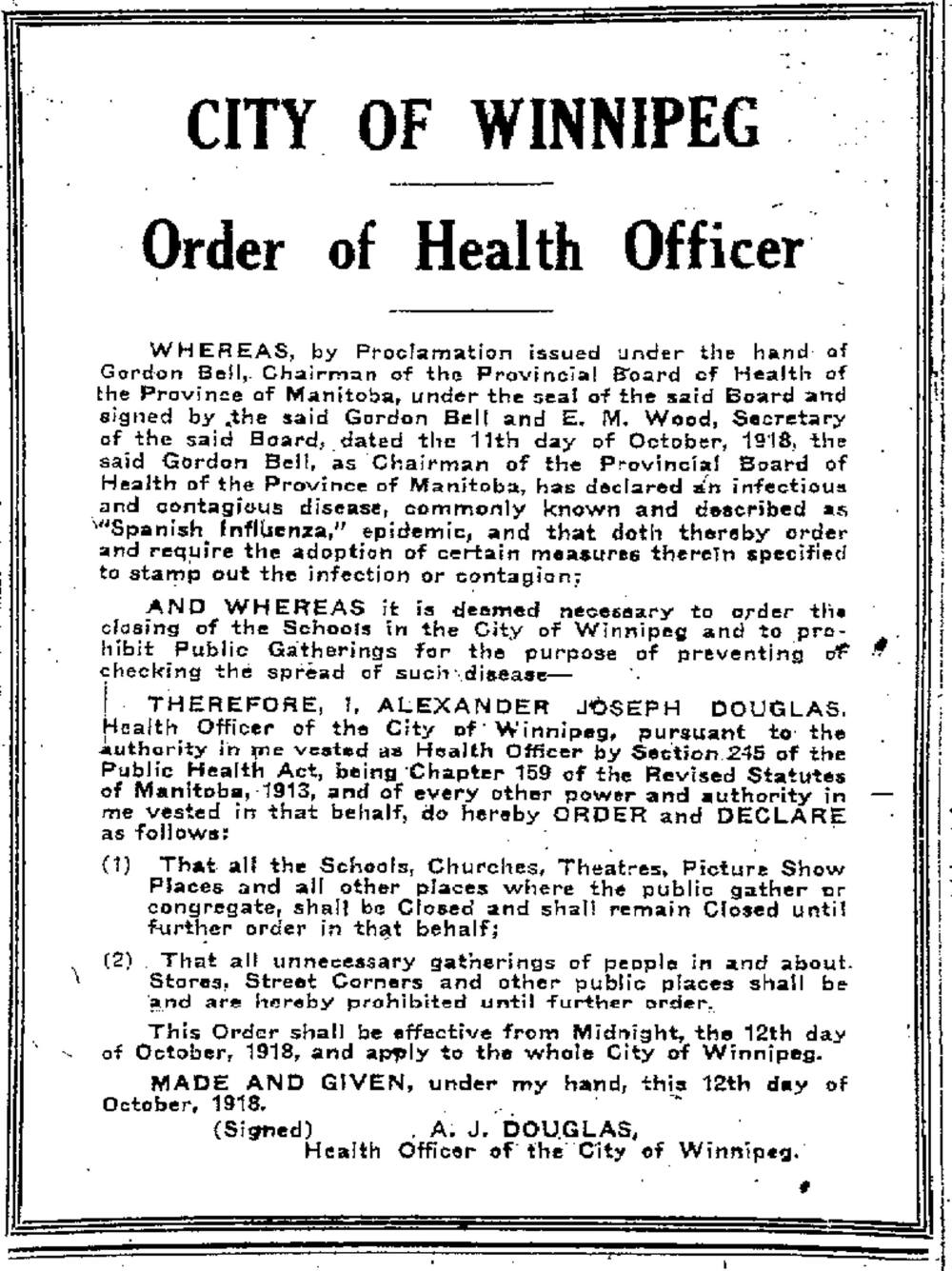

Meanwhile, city officials shut the city down. The ordinance coincided with Dysart’s death. The city proclaimed a ban on all public gatherings, and communities across the province followed suit.

All Manitoba schools were closed, including universities and colleges, and all church services were cancelled. Entertainment venues such as movie theatres, dance halls, even public bathhouses, were shuttered.

Some church leaders balked. One reverend said this was the time when people needed the church most and churches should be open for people to pray. But ultimately, the places of worship fell into line.

Theatre owners put up the most resistance. The Free Press reported theatre owners claimed they were going broke and threatened legal action if the city didn’t allow them to open. The city assured them the public ordinance wouldn’t last more than three weeks. It lasted 46 days.

Visiting hours at the Winnipeg General Hospital were abolished. Personal care homes were closed to all visitors. The Manitoba Sanatorium for Tuberculosis in Ninette was also closed to visitors.

Other cities, such as Selkirk, also observed bans on public gatherings, too. The Manitoba Rolling Mills in Selkirk was closed because so many employees were sick. “The town is closed up tight, all the churches, schools, and places of amusement being dark. Placards are on scores of houses,” a Free Press reporter wrote.

That was another thing: placards. In Winnipeg, when you reported the flu, your home was supposed to be placarded as a kind of quarantine to let others know not to enter. However, the placarding was only carried out half-heartedly and in some ways it likely prevented some people from reporting the flu because of the stigma that placards implied.

The telephone system was affected. So many operators were off sick that authorities urged people to use the phone for emergencies only.

The Alberta government went a step further and proclaimed it against the law to go out in public without a mask. These weren’t the disposable kind like today but were made of cloth, typically five-ply cheesecloth.

Masks helped health-care staff where they could be changed and washed regularly. But the masks worn by the public were not kept to the same hygienic standards and health officials today believe they likely trapped more germs than they kept out, including potentially lethal bacteria that cause bronchitis or bacterial pneumonia.

A famous photo shows Free Press newspaper carriers decked out in masks before heading out on their paper routes. Some towns in Manitoba also made masks mandatory, like in Minnedosa where masks were required in public places, including businesses. The same things were taking place not just across North America but around the globe.

One bylaw the City of Winnipeg vowed to enforce with vigilance was this one: “No person shall spit on any sidewalk or pavement crossing, any passageway, stairway or entrance to any building used by the public, or in any church, theatre, assembly room, music hall, concert hall or lecture all, railway depot, railway or steamboat waiting room or to any room, hall or places to which the public resort, or in any streetcar or public conveyance except in a proper receptacle.” It was a $50 fine or jail.

Medical science didn’t understand the Spanish flu. There was no vaccine like today. Viruses hadn’t been discovered yet. Even Kleenex hadn’t been invented. The disposable tissue paper was still six years away.

But health authorities knew enough from experience that coughing, sneezing and spitting were ways that influenza spread. They also knew hygiene was important, although standards back then weren’t as advanced as today.

There was much they didn’t know, however, like that flu has an incubation period of two days, meaning a person can be a symptom-free host for 48 hours and still transmit the infection.

Health officials urged the public to abide by recommendations on hygiene. During the education campaign, Dr. A. J. Douglas, Winnipeg’s medical health officer, made a strange plea for people not to be fatalistic. “We must not put up our hands and say, ‘It’s an act of God!’” he said.

There was a big rush to obtain a serum that was supposed to repel Spanish flu. An anti-influenza inoculation was developed at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a local health official went to retrieve it. Health labs in Winnipeg replicated the serum. The Manitoba Medical College began producing 7,000 to 10,000 anti-flu vaccines daily.

It was distributed for free. Health workers and military personnel were first to be inoculated and it went down the line from there. For example, one railway took about 20,000 units of serum to inoculate its employees across Western Canada. The number of rail passengers had plummeted in response to the flu and those who did travel by rail wore masks.

Initial reports in Winnipeg were that the serum worked to perfection and made a person completely immune against Spanish flu. That was contradicted days later by reports that it made no difference whatsoever. Finally, reports said there was no proof it was effective, but it couldn’t hurt.

There was little human drama reported in the Free Press pages. Instead, coverage involved mostly health authorities passing along the latest statistics: a daily ledger of how many new cases of Spanish flu were reported, how many deaths, in what neighbourhoods, towns, etc. The daily quantification recalled bloody tyrant Joseph Stalin’s famous quote that killing one man was murder but killing millions was a statistic. The Spanish flu story was conveyed by statistics.

As many as 55,000 people across Canada died from Spanish flu. The death toll was so great that Toronto began allowing funeral services on Sundays. Not that they were well attended. Many people avoided funerals altogether and any other place where a crowd gathered.

Spanish flu roamed into all corners of the countryside. In a church cemetery in Hochfield, just outside Steinbach, a stone memorial honours 20 children who died of Spanish flu. The population of Steinbach was less than 500 at the time. In Saskatchewan, rural death rates were twice the province’s average, with cases reported where entire families were found dead and livestock was starving.

The disease took more time to reach First Nations but was deadlier when it did. There is a mass grave for Spanish flu victims in Sagkeeng First Nation. On Feb. 6, 1919, it was reported in the Free Press that 107 people had died in Norway House, and 125 in Cross Lake, both communities northeast of Lake Winnipeg. Among first nations in British Columbia, the death rate was 46 per 1,000. That was similar to the indigenous Maori people of New Zealand, where the rate was 42 per 1,000.

The newspapers didn’t delve deeply into personal tragedies but a few came to light. Of all things, Winnipeg was embroiled in a civic election during the pandemic. Almost as amazing as the death toll back then was society’s stubbornness to carry on.

During the election, influenza claimed the life of Thomas (Woodie) Gray, the son of Alderman Herbert Gray. The son had been too sick to even know that his wife and newborn child had died two days earlier. The couple’s three-year-old, Gordon, was the sole survivor.

Thomas died on Nov. 26, three days before voters went to the polls. The tragic deaths absented Ald. Gray from the campaign trail. He was not only grieving the loss of his son and son’s family but caring for five of his remaining eight children who were also sick with the flu. He was still re-elected.

Every day brought tragedy. A young man named John Hughes from Winnipeg had left for Siberia to serve in the Canadian military. Shortly after his departure, his entire family was erased by Spanish flu: his mother, sister and brother.

The date Oct. 24 was typical. Among those dead from Spanish flu were Harry Lawler, of the Canadian Army Medical Corps., 27; Alex Black, son of businessman George Black, 29; and John T Wanlass, 19.

Contrary to reports days earlier that the pandemic was on the wane, there were 52 deaths on the weekend of Nov. 9-10. They included a Capt. Mitchell of the No. 4 fire hall on Gertrude Avenue, age 40; Miss Jane Ruby Conley, 25; Victor J. Havens, prominent farmer of Lockport, 37; Murray Gardiner Newell, 19; Harold Simmons, 17; Mrs. Catherine F. Younger, 25, whose husband Pte. H. Younger, “is at present a prisoner in Germany;” E. F. Morran, a theological student at Wesley College.

Thursday, Nov. 21, was another great day for the Grim Reaper. Flu deaths included Mrs. Mary Emma Swanson, 21; Mrs. Anita Margaret, 31; Joseph Taford, 33; Henry J. Cross, 30; war bride Mrs. Grace Mary, wife of Sgt. W. Thomas, of 116 Hart Avenue in Elmwood, leaving behind a husband and four children.

Notice the ages of the deceased?

On Oct. 22, Dr. Gordon Bell, chairman of the provincial board of health, divulged to the media that the medical community was completely baffled. The typical distribution pattern of flu is U-shaped with the oldest and youngest ages suffering the highest mortality. With Spanish flu, he said, “the majority of fatalities occur among young adults.”

Instead of being U-shaped, Spanish flu’s distribution curve was W-shaped, with the centre peak the highest, striking the healthiest population between the ages of 20 and 40.

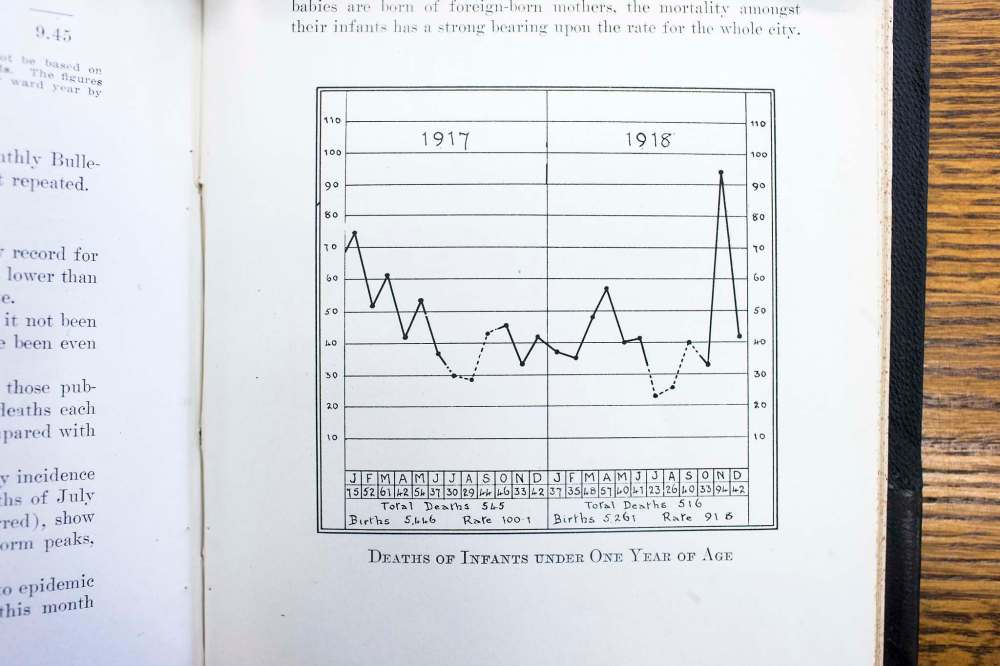

And what about those age groups typically most vulnerable? Officials weren’t seeing the number of deaths they expected. That was confirmed later when statistics showed the lowest rate of baby deaths on record despite the pandemic.

Part of that was attributed to a new “milk depot program” to ensure that newborns received nourishment, but not all of it.

“Children and elderly people,” Bell told reporters, were “escaping in a way that is impossible at present to explain.”

***

In the midst of the pandemic, or plague, whatever you want to call it, there were countless unsung heroes.

Doctors and clergy, virtually all male back then, were certainly at the forefront of the fight. Doctors became distraught at how helpless they were to save patients against the pandemic, said Esyllt Jones, University of Manitoba history professor.

“It was very deflating, very difficult at a personal level, dealing with so many deaths all at once,” said Jones in an interview. “Physicians speak about how demoralizing it was not to be able to help people. They had very few tools in their toolbox.”

It’s not known how many physicians died but there was one fatality noted at Winnipeg General Hospital, in its annual report from 1918.

“It is with regret that we have to record the death of Dr. Fred Orok, a member of the intern staff, who contracted Spanish Influenza whilst carrying out his duties as pathological intern,” the report says.

But the real heroes in the fight were women. First the nurses, then the volunteer nurses.

There was almost an immediate shortage of nurses. Winnipeg women volunteered to fill the breach by working with flu victims both in hospitals and by making house calls. One volunteer group, the Margaret Scott Nursing Mission, visited 2,000 homes alone.

Hundreds of women stepped forward. They took crash courses in nursing, like that provided by St. John Ambulance. Because schools were closed due to a ban on public gatherings, many female teachers stepped into the breach. About 60 teachers were working as nurses within weeks of the flu’s arrival.

More and more women stepped forward. By late November, it was reported 638 women had volunteered as nurses to enter people’s homes and comfort the sick. At times, volunteer nurses entered houses to find entire families ill and dying. Some of the female volunteers suffered breakdowns from the stress.

There are countless stories of their courage. In one case written up in the Free Press, a volunteer nurse entered a downtown apartment to find a baby and its two parents dying in a one-room suite. The parents were too sick to even get up to care for their child.

The nurse stayed up with the child all Monday night, all day Tuesday, and Tuesday night when another volunteer arrived to help. It wasn’t the norm but volunteer nurses often worked double shifts.

“Together they wrestled with death for the life of the little one,” the Free Press reported.

It was a wrestling match they would lose. The baby boy died Wednesday morning.

“The physical and psychological demands placed on the volunteers were extremely high,” writes Jones in her extraordinary book, Influenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg (University of Toronto Press).

The volunteer effort stands out for its gender bias. Women volunteering with charitable group Diet Kitchen fed several thousand families during the crisis. The Women’s Labour League helped raise funds to pay for funerals.

The cost of funerals was a major issue, rates were bumped up because undertakers had more business than they could handle. Many families were devastated by multiple deaths and often unable to work because of the ban on public gatherings.

Meanwhile, it was reported that former Manitoban Nellie McClung, now living in Edmonton, had recovered from a “severe attack” of Spanish flu. McClung had set up a program to do laundry of the sick in the basement of a Methodist church so families in Edmonton could have disinfected clothes and bedsheets.

Another phenomenon taking place was that female volunteers from the upper and middle classes were volunteering, often entering homes in the poorest neighbourhoods. For a short time of about six weeks, the class barriers came down. In her book, Jones describes this as “empathy across social boundaries.”

“Middle-class women entered slum neighbourhoods, many of them for the first time. They entered into (their homes) to provide intimate bodily care and to witness the individual and family at their most vulnerable,” she writes.

In many cases, relationships endured after the crisis was over. Surviving families often stayed in touch with the volunteers who helped save their lives, exchanging cards and gifts, such as chocolates, to try to say thank you.

Jones calls it “an extraordinary encounter, profoundly affecting individuals, and picking at the edges of social hierarchy in Winnipeg society.”

But both professional and volunteer nurses were putting themselves in extreme danger. They were in “the contact zone,” as Jones describes it, at high risk of catching the contagion.

It came at a cost.

At least seven professional nurses died from Spanish flu in Winnipeg.

The Winnipeg General report states that one pupil nurse — basically all the nurses in hospitals except supervisors were pupil nurses back then, while graduates worked privately outside hospitals — died from influenza. Her name was Florence Smith. Another fatality was graduate nurse Eva McNee, who died at King George Hospital.

Trying to count the fatalities among volunteer nurses is more difficult. But by Nov. 25, it was being reported that at least four volunteer nurses had died. One of them was Mrs. S. Kaufman. It seems an indignity that the wife’s given name isn’t even mentioned in such cases.

Another volunteer nurse who succumbed was Mrs. Alfred Pocock. She had been married for three years. She left behind an 18-month-old child. Another volunteer was Miss Anna Gibson, a teacher at La Verendrye School.

Among those registered, at least nine volunteer nurses died and that’s just for the city proper, excluding many of the suburbs that make up the city today.

They volunteered in the countryside, too. Miss Winnifred G. Goulding succumbed to the flu after nursing a family of 10 back from a severe attack.

“Pandemic preparedness now is very much focused on the role of the experts and health-care providers and doesn’t consider very much how one might mobilize a volunteer network. At the local level, that work was so important in the pandemic.”–Esyllt Jones

On Nov. 21, Winnipeg Mayor Frederick H. Davidson announced the city would erect a plaque to honour the brave women who volunteered in the face of death to battle the pandemic. It never happened. Davidson lost the election on Nov. 29 and the new council never took up the resolution.

Jones thinks that’s a historic omission. She believes the women warrant a plaque or monument of some kind. There isn’t a statue or plaque anywhere in Manitoba, or anywhere in Canada, to mark the volunteer nurses, as far as she is aware.

The role of women needs to be remembered not just for their sacrifice but for the lesson they provide in future crises, she said. If there is another pandemic, people will need to step up and volunteer.

“I do wish it was recognized to a greater extent. It would make people think differently about how you survive events like a pandemic,” said Jones.

“I say this partly because pandemic preparedness now is very much focused on the role of the experts and health-care providers and doesn’t consider very much how one might mobilize a volunteer network. At the local level, that work was so important in the pandemic.”

***

In her book, Jones compiled some statistics about the flu’s age distribution in Winnipeg.

With children, it was infants ages three and under who were the most vulnerable. About 150 children in that age group died from Spanish flu in Winnipeg, while about 100 from ages four to nine died. Another 100 from ages 10 to 19 lost their lives.

Then look at the number for those ages 20 to 39. In Winnipeg, of the 1,216 registered deaths, 60 per cent were men and women between ages 20 and 39, or nearly 750 deaths.

Meanwhile, the smallest number of deaths were people over the age of 40. It seems as though that age cohort had somehow developed some immunity to the genetic strains in Spanish flu over their lifetimes.

The demographic breakdown was “shocking and unexpected,” writes Jones. Most victims were mothers and fathers of young children.

The Spanish flu resulted in scores of broken families. Families lost brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, mothers and fathers. Single mothers and single fathers were left behind to care for surviving children, and orphanages swelled with children made homeless. And these fatalities were on top of the number of servicemen who didn’t return from the First World War.

There was no satisfactory explanation for the flu targeting the healthiest population before the publishing of a paper in 2007 in Nature magazine. The study led by Darwyn Kobasa, a research scientist at the Public Health Agency of Canada, determined it wasn’t Spanish flu that was so lethal but the body’s reaction, or over-reaction, to it that killed the patient.

Kevin Coombs, a professor of medical microbiology at the University of Manitoba’s Max Rady College of Medicine, recently published findings that support Kobasa’s premise.

Coombs, originally from New York state, said what drew him to study viruses is “how something so small can cause so much misery, how such a simple organism can take over a cell and force it to do what the virus wants it to do.”

The Spanish flu virus is kept in high-security storage in several international labs, including the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg. The virus is held at the federal laboratory for research into the characteristics that cause Spanish flu to interact with cells so severely.

Coombs, with co-authors Kobasa and Charlene Ranadheera of the Public Health Agency of Canada, used the virus in their research. Whereas Kobasa’s study had demonstrated the immune system’s over-reaction at the cell level, Coombs found a similar response at the protein level.

Coombs compared it to anaphylactic shock, a severe allergic reaction to an antigen where people use an EpiPen to counter the body’s extreme response. “It’s not really the thing you’re allergic to that does you in, it’s how you respond to it,” he said.

The lethal flu virus caused what is called a “cytokine storm.”

Cytokine is a molecule that cells use to communicate with each other. Coombs’ group was the first study to show that proteins communicated with each other to create an overproduction of immune cells. The immune cells surge into the lungs and the fluid buildup becomes so great that people can’t breathe.

“You got so much produced that a large number of people were literally drowning in their own secretions,” he explained.

We get fluid buildup with common flu but not like a pandemic. These are inside fluids that fill your lungs and not related to, say, a runny nose from the seasonal flu.

That explains why the health of 20- to 39-year-olds was hit hardest. They had the most robust immune systems, and the Spanish flu turned those rigorous immune systems against them.

The goal of flu research such is to find a vaccine, or “silver bullet,” for pandemic flu, Coombs said. “The big thing with flu is that the virus changes so rapidly that we have to get a different flu shot every year,” Coombs said.

The hope is research will find the shared trait among viruses and then develop an agent to render them harmless now and in the future.

“Maybe we can find something all flus have in common and that would be common to all the next flus yet to come, and then nip it in the bud,” he said.

***

Heading into 1919, the death toll from Spanish flu kept rising.

A total of 63 and 64 Winnipeggers died in the third and fourth weeks of December; 54 deaths in the week ending Jan. 4; 51 deaths in the week ending Jan. 11.

There were still some bad days ahead in March when the third and final wave of Spanish flu struck.

By the summer of 1919, it was gone. It wasn’t from anything medical science had done. It was just that those who had contracted the disease had either died or developed immunity.

Some scientists think the world is overdue for another flu pandemic on the scale of the Spanish flu.

There have been reappearances of deadly viruses. Most recent was the swine flu, or H1N1, which claimed 200,000 lives worldwide in 2009. Swine flu had a mild version of the W-shaped distribution pattern but the middle peak wasn’t nearly as great as with Spanish flu. The Asian flu in 1957 and the Hong Kong flu in 1968-69 were deadlier, claiming about a million lives each.

But a century ago, people were no match for a pandemic such as Spanish flu.

“They weren’t prepared,” said Myrna Dyck, epidemiologist for infection prevention control for the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, in a recent interview for Wave magazine, an online publication by the WRHA. (An earlier version of this story ran in www.wavemag.ca.)

“They thought things like the Black Death existed only in history books. They didn’t realize that the level of a pandemic could exist again,” she said.

Some of the treatments at the time included using arsenic, mercury, strychnine, Aspirin, alcohol, and even bloodletting in rare cases, to, in theory, purge the body of its poisons. The latter was a mistake because the body was already dehydrated.

If a Spanish flu struck today, it wouldn’t be as lethal, but it’s hard to say how lethal it would be.

Today we are healthier, we have better sanitation, better nutrition and diets, antiviral medicine such as Tamiflu that if taken within the first four days of symptoms can shorten the duration of flu, antibiotics to prevent secondary infections such as pneumonia, antibacterial soaps (available everywhere, including dispensaries on workplace or restaurant walls), and people are dedicated to keeping active lifestyles.

“All of these things make us healthier and make it easier for us to survive a virus,” Dyck said.

“We wash our hands and we actually understand if we wash our hands it will make a difference. I don’t think they quite got it yet back then. Even their treatment for tuberculosis back then was opening windows.”

We’re also taught that coughing into the crook of your elbow is preferable to coughing into your hand because you’re less likely to touch as many things with the inside of your elbow. You’re not likely to rub your eye or your nose or shake someone’s hand with the inside of your elbow.

Neither do you want to touch your face after handling money, or while on a stationary exercise machine in a public gym. At the risk of turning people into germophobes, these are practices that can help prevent the spread of flu and are already being taught to children in kindergarten.

And, of course, today we have vaccines. It is sometimes forgotten that even the seasonal flu we encounter every year would leave more people sick and dead if not for the vaccines that are distributed annually. Even so, 46 deaths with lab-confirmed influenza were reported in Winnipeg last year, nearly all of them adults over the age of 60.

Every year the World Health Organization reviews the prevalent flu mutations around the globe to determine the vaccine for the next season. That vaccine will be issued for the entire world.

The WHO must make its vaccine six months in advance, and uses southeast Asia as its guidepost. That’s typically where the flu will start and then migrate westward through the Northern Hemisphere.

The reason it starts in southeast Asia, particularly China and Indonesia, is because many of these flu viruses start in the digestive systems of birds, and to a lesser extent in pigs. Viruses can often find refuge in host animals without causing ill effects. It becomes a much bigger issue if an avian flu or porcine flu mixes with human flu. That’s where so-called swine flu came from in 2009.

So where’s the highest population density of humans, chickens and pigs? China. It has the world’s largest human population at 1.4 billion – 20 per cent of the world – and produces nearly half of all pigs in the world, and about a quarter of the world’s 19 billion chickens.

Generally speaking, the health authorities strive to create a vaccine that is 80 per cent effective against any particular strain of flu. More often than not, though, the vaccine is about 50 to 70 per cent effective. That’s not bad considering the flu virus is constantly mutating, making it difficult to produce a vaccine for the virus that is in circulation.

But 2017-18 was a bad year. The WHO-developed vaccine, using all the data coming from southeast Asia and elsewhere, performed at just a 36 per cent success rate, and 25 per cent for the most common strain of flu that year, H3N2.

“It’s basically because they’re guessing what flu is going to be circulating six months in the future, and sometimes they get it and sometimes they don’t,” says Coombs.

This is a good year, however. Early results with this year’s vaccine were very successful in Australia, which gets its winter and therefore flu season about half a year before us, and that has continued into North America.

So your odds of avoiding flu this year are much better, so long as you get your shot.

But even if you take the vaccine, it wouldn’t save you if a pandemic outbreak occurred. A pandemic is a type of virus that mutates into more virulent and deadly strains. If a pandemic broke out today, there would likely be about a six-month lag before a vaccine could be developed and distributed, Dyck said.

So if a virulent and fatal mutation struck now, there would be no vaccine to deal with the first wave, if it follows the pattern of Spanish flu, and it would be an extreme rush to vaccinate before a second wave.

Manitobans vote with their naked shoulders when it comes to how they feel about flu shots. Last year, only 22 per cent of Manitobans took up the government’s offer of free vaccination.

The relatively low immunization rate frustrates those working in flu prevention. Even if a vaccine in any given year isn’t 100 per cent guaranteed to beat back the flu, it will still eradicate some of its components and lessen the symptoms.

“If you got vaccinated before you got influenza, the likelihood of you dying is a lot less… Why wouldn’t you take it?”–Myrna Dyck

“Everyone says it might not work, it only worked so well last year. Yeah, it may not have been perfect but if you got vaccinated before you got influenza, the likelihood of you dying is a lot less,” Dyck said. “It actually protects you from the severity of the disease. It will protect you even if you get the influenza. You will not get it as bad.”

That’s why Dyck can’t understand why more people don’t get vaccinated. The Manitoba government makes the flu vaccine shots available free of charge

“It’s frustrating. It’s free. Why wouldn’t you take it?”

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Monday, February 18, 2019 9:09 AM CST: Includes age of Claire Dysart