A rebel with a cause For Manitoba's First Nations Family Advocate, shaking up the status quo all part of mission to reduce the number of child apprehensions

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/02/2019 (2497 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Cora Morgan is often the public face of private grief.

Since 2015, she has fielded thousands of calls from Indigenous families needing help navigating the maze that is Manitoba’s Child and Family Services system.

She has frequently made national news along the way, including last month when she took media questions at her office, on behalf of a family whose newborn was apprehended at St. Boniface Hospital Jan. 9.

That apprehension, which was broadcast live on Facebook, sparked widespread public outcry about the over-representation of Indigenous children in the child-welfare system. It also showed more than a million viewers an event that Morgan hears about on a near-daily basis.

There’s a white-board at her Smith Street office, which lists about a dozen expected “birth alerts” in the coming months; labelled by due date for mothers who are deemed “high risk” by CFS.

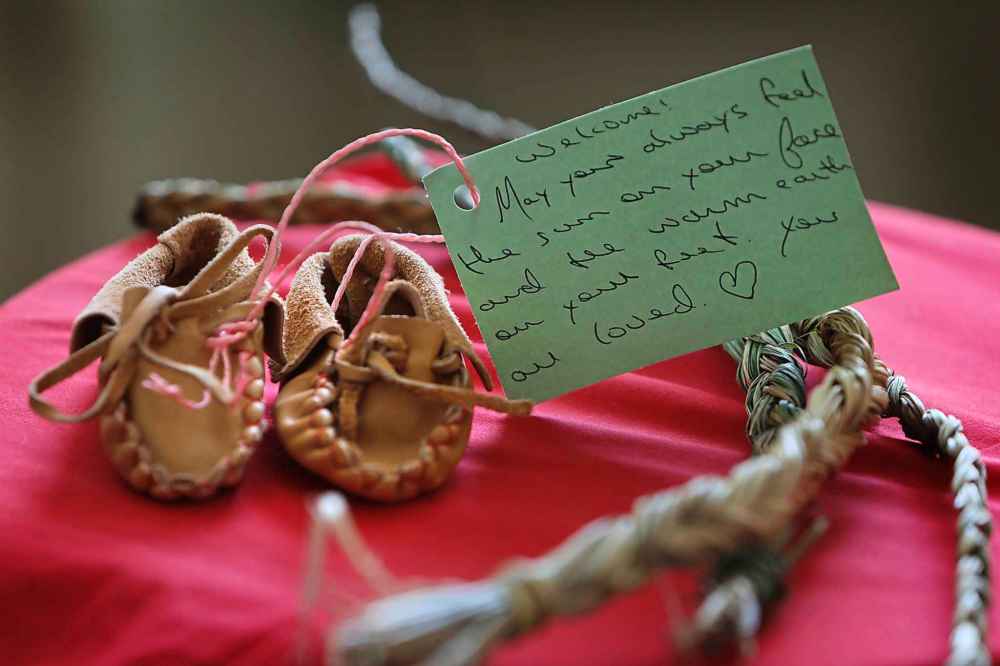

There are also buckets and shelves full of handmade moccasins, which are gifted to mothers whose children are apprehended, Morgan said. It’s a symbolic gesture, encouraging them to not give up hope of getting their kids back.

Remarkably, when she took on the First Nations Family Advocate role with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC), Morgan had zero professional experience working in child welfare.

She didn’t know what birth alerts were, let alone how frequently they happened — 558 times in the 2017-18 fiscal year, according to government data, with 282 newborns taken into care.

“I’m not a social worker. I’ve never worked in child welfare. I’ve worked with families and supported young people and have developed programs and services,” Morgan said, referring to her past work in restorative justice.

She served as executive director of Onashowewin Justice Circle for nearly eight years and as a consultant with the non-profit Ka Ni Kanichihk before that.

In a wide-ranging sit-down interview this week, she talked about the through-line in her work: an unwavering sense of wanting to right wrongs.

“I don’t care if it’s in the (Child and Family Services) Act. If it’s wrong – if it feels wrong, if it’s harming someone – then it’s wrong,” Morgan said.

“Just because the Province of Manitoba says you can do it in their standards or their act, it doesn’t make it right.”

● ● ●

The AMC hired Morgan as their family advocate partly because of her inexperience, said former Grand Chief Derek Nepinak in a separate interview this week.

“I did not want necessarily to hire someone who was OK with the practice of apprehending children from their mothers or their fathers,” he said. “I wanted someone who had not been in an environment where they had been indoctrinated or led to believe that is a practice that is acceptable.”

Her position was the first of its kind created in Canada, according to the assembly.

In 2014, after consulting with First Nations leaders across the province, the AMC put together 10 recommendations to improve child welfare in Manitoba, assembled in a report called Bringing Our Children Home.

No. 2 on the list was hiring an advocate focused exclusively on helping Indigenous families, whose children constitute an overwhelming majority of CFS wards — nearly 90 per cent of the close to 11,000 kids in care in Manitoba.

Morgan remembers reading about the new AMC position in the Free Press and how the staff at Onashowewin pushed her to apply.

Almost every young person she met at Onashowewin had prior involvement with the CFS system, she said. Maybe this was her chance to stop the trend.

“You’re seeing a commonality among all of them and that was that they had lost value for life. They didn’t care whether they’re in the Manitoba Youth Centre or in a group home or any of that,” she said. “For me, that was tragic.”

In her job interview, Grand Chief Nepinak asked what she’d do on her first day and Morgan remembers saying: “Well, we’re going to go to ceremony.”

On that first day in June 2015, they held a sweat lodge and an elder gifted their office with the Ojibwe name Abinoojiyag Bigiiwewag. It translates to: Our children are coming home.

● ● ●

Though she’s often making headlines defending others, Morgan’s own story is lesser known.

She’s the mother of two boys, ages six and eight, who love to play hockey. She’s from Transcona and has family ties to Sagkeeng First Nation.

She’s soft-spoken and warm in person, and said her life is guided by the seven sacred teachings: love, respect, courage, honesty, wisdom, humility and truth.

And as inoffensive as she sounds, Morgan has become one of the most polarizing figures in the child-welfare system.

Some CFS agencies will work with her, sharing information at families’ requests. But others won’t talk to her, she said, although she refused to name specific agencies that don’t cooperate.

One source who works in the child-welfare sector, but wasn’t authorized to speak publicly, said “Cora has definitely made a big splash” in the system. The source said not everyone supports her line of work.

Unlike the office of the Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth, currently held by Daphne Penrose, Morgan’s office doesn’t have a legislated mandate to investigate CFS-related issues.

That can mean she’s operating in the dark, possibly missing important parts of families’ stories.

‘People think that she’s a disturber, but what she’s doing is… for the children. For the children to have a right to have a mother and father; for our children to be able to grow up in our culture and language and teachings’

– Grandmother Chickadee Richard, one of Cora Morgan’s co-workers

This week, court documents revealed the reasons why CFS took the two-day-old baby girl from her Indigenous mother in January.

An agency worker voiced his concerns in an affidavit, including allegations about the mother’s drug use, mental health issues and history of past child neglect.

Morgan said she didn’t know the mother’s whole history when she went to bat for her last month, but she is still supportive of her mission to get the baby back into her family’s care.

“We didn’t have tons of back story on her, but you know, she was wanting to do the responsible thing for her baby, and that’s what we would support,” she said.

The mother sought help for her addictions and designated an aunt to take care of her baby, if she wasn’t able.

In court filings, CFS said a family member suggested by the mother didn’t pass a background check.

“We’re not going to ever condone a child being in an unsafe situation, but our point here is moreso that there’s better ways of doing things,” Morgan said.

She and the assembly want to see Indigenous children safely raised by their own community members, which has become a shared priority with Ottawa.

The AMC is working with the federal government to develop new child welfare legislation, which would pivot control of CFS from the province to First Nations.

● ● ●

Although no one from the provincial government agreed to an interview about Morgan’s work this week, Families Minister Heather Stefanson sent a prepared statement by email saying she has a “good working relationship” with Morgan.

Morgan said she’s never met Stefanson, but she used to call her predecessor, Scott Fielding, on the phone as she was witnessing newborn apprehensions happening.

It was an attention-grabbing move she also pulled on former NDP Family Services Minister Kerri Irvin-Ross. Irvin-Ross wouldn’t comment on how Morgan operates.

During a joint press conference in 2015, Tory opposition critic Ian Wishart decried Morgan’s exclusion from meetings with CFS officials.

“Aboriginal children have a First Nations advocate and a very effective one,” he said of Morgan at the time. He also called her “fearless and outspoken.”

Current AMC Grand Chief Arlen Dumas underlined what already seems obvious — that government doesn’t take well to Morgan’s criticism.

“They don’t appreciate that, in the big picture, when we actually do what we’re going to do, we’re going to be redirecting a lot of resources that come to the provincial coffers. And I know that people don’t like that,” Dumas said, of federal money that gets transferred to the province for child care.

“But at the end of the day, that money that goes into those provincial coffers is supposed to be for those children. So it shouldn’t even be an issue.”

Morgan said she’s not going to waste her time on “futile exercises” like calling the family ministers mid-apprehension anymore. She is plenty busy as is.

What started as a solo advocacy office has ballooned to include a small army of 32 staff, all of whom are First Nations, Métis or Inuit.

Thanks in part to an $800,000 shot of federal funding in 2017, the First Nations Family Advocate office now offers day programs, like sharing circles and parenting programs; a child-minding room full of toys; and a kitchen where staff make soup, tea and other snacks to share with guests.

One of Morgan’s co-workers, grandmother Chickadee Richard, calls her a “brilliant” leader, while highlighting critics’ qualms.

“People think that she’s a disturber, but what she’s doing is… for the children,” she said. “For the children to have a right to have a mother and father; for our children to be able to grow up in our culture and language and teachings.”

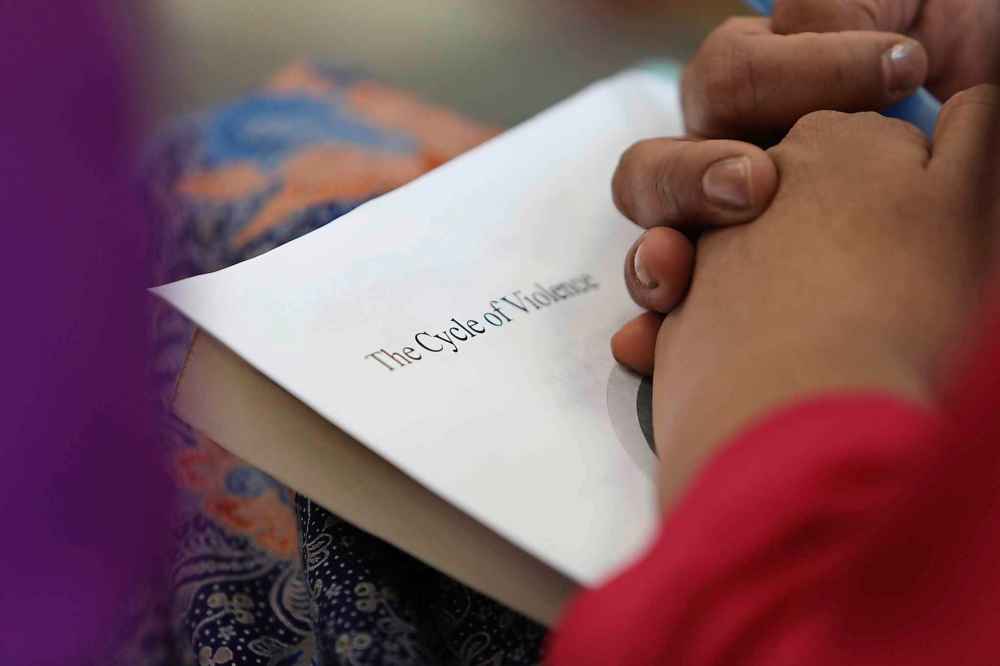

Like Morgan, she compares the persistence of CFS apprehensions to when Indigenous kids were forcibly removed from their families and sent to residential schools.

Morgan believes the current practise is worse; at least with residential schools, parents usually knew where their children were going.

So has her work made a difference?

“I don’t know,” she admits. “I know that we’ve helped hundreds of kids go home to their parents.”

She’s expecting to release a report in March, with exact statistics outlining the ways her office has helped families.

Nepinak would argue that yes, Morgan has made a crack in the status quo, as he hoped she would. He believes she deserves the same respect as elected officials.

“We prop up people into lofty political hierarchy. She’s not part of that,” he said.

“She’s part of the real change makers of our time.”

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @_jessbu

History

Updated on Friday, February 8, 2019 7:36 PM CST: Fixes detail