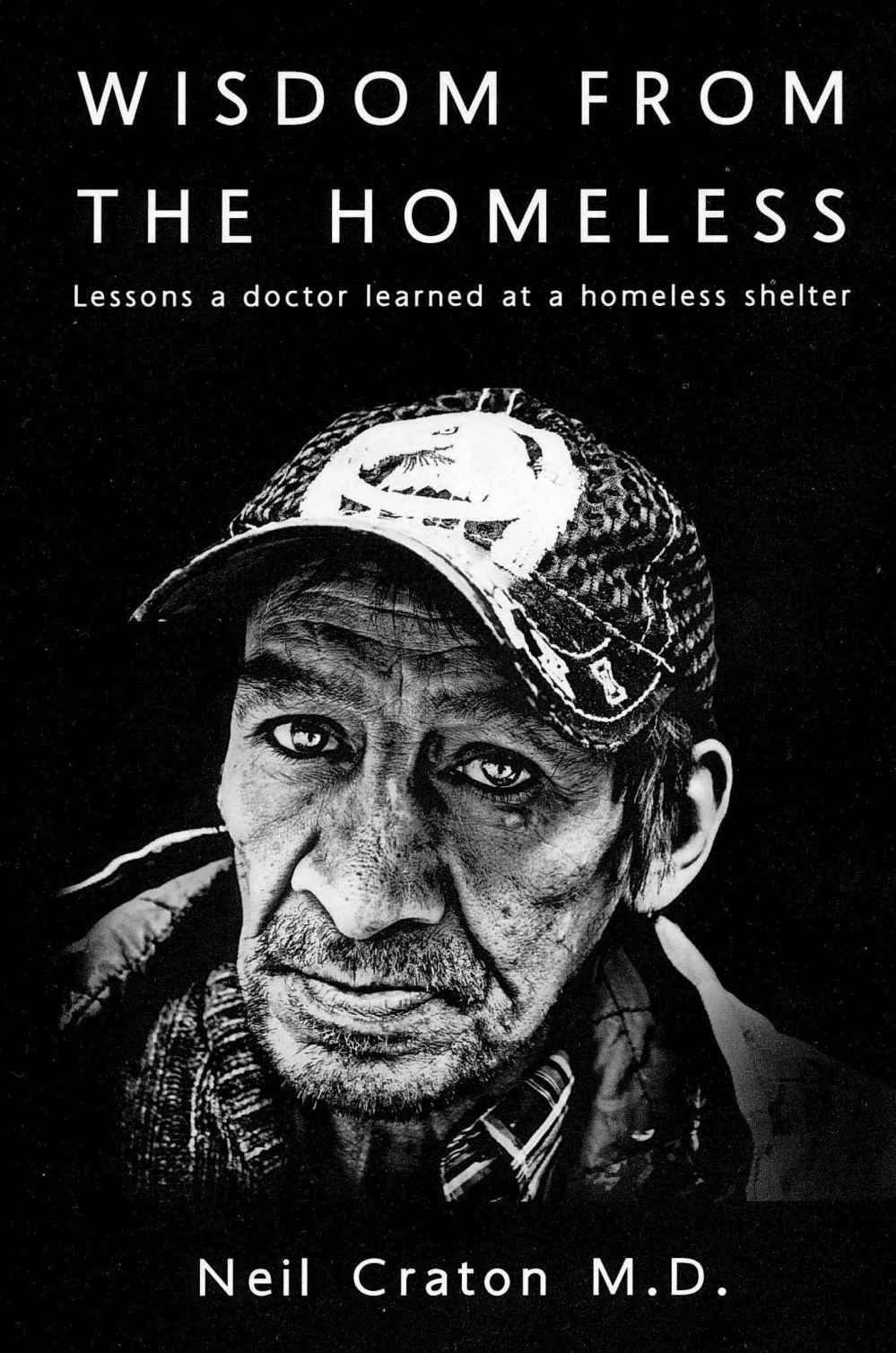

At home, healing the homeless High-profile physician's book follows his discovery that tending to Winnipeg's most vulnerable is a powerful prescription for the soul

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/01/2019 (2513 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For most of his 35-year medical career, Dr. Neil Craton has treated the painful and potentially career-ending injuries of this city’s elite athletes.

A leading expert in sports medicine, the 59-year-old physician has been the Winnipeg Blue Bombers’ team doctor for 23 years, and spent 25 years looking after the health of the Canadian women’s national volleyball squad.

In 1994, he opened Legacy Sport Medicine Clinic on Meadowood Drive in St. Vital, and in the years since has provided care and compassion for a never-ending stream of bumps, bruises, fractures and tears suffered by elite athletes and well-to-do weekend warriors.

Despite a career dedicated to high-level competition, the most important lessons this doctor has learned in life have been taught to him by the most vulnerable members of society, Winnipeg’s homeless.

Every second Friday for the past 10 years, Craton has volunteered his time treating the profound injuries and illnesses suffered by patients at Siloam Mission’s medical clinic in the city’s core.

His experiences at the clinic have been life-altering, and led him to write an unflinching, heart-rending new book, Wisdom from the Homeless: Lessons a Doctor Learned at a Homeless Shelter.

Craton’s goal in writing the book — the proceeds will go to support Siloam — was to offer Winnipeggers a window into a world most will never visit, and to share the remarkable lessons he’s learned.

It’s divided into 21 chapters, each highlighting the seemingly tragic case of a homeless patient, but Craton shares their stories as lessons in resilience, courage, the ability to find joy amid suffering and the indomitable strength of the human spirit.

The stories are true, although the names have been changed to protect the identity of the patients. Each story is seen through the lens of his Christian faith, but Craton says “this book needs to be accessible to all people, because these lessons are good, I think, for all of us.”

•••

“Sometimes silent screams are the loudest.”

The book begins with the story of a young man who didn’t share the typical rough-around-the-edges look of most shelter clients.

“The patient I was about to see had the usual tattered attire, but his facial features were remarkable,” Craton writes. “In fact, I wondered if he was an actor playing a part. He was an Indigenous man in his early thirties with a chiseled jaw and shimmering black hair cascading below his shoulder, hair that could have come straight out of a shampoo commercial.”

But the man had the distinct odour associated with glue-sniffing and the stench of anaerobic bacterial infection. More remarkable, he didn’t — or couldn’t — speak, and refused the offer of pen and paper, merely nodding toward a temporary cast on his left arm.

“Once the splint was off, it was apparent that my patient had major problems. The skin was open and infected, and his wrist was so badly broken that the bones moved freely. My silent patient was suffering from an infected, unstable and open fracture that had been unattended for days.”

The man was sent to hospital for emergency surgery, but two months later reappeared at the clinic, his left arm amputated below the elbow. Again, he didn’t utter a word, but it became clear his stump was infected and required treatment.

Writes Craton: “The man endured his pain in silence. I remember feeling frustrated that there was so little I could do to change his situation… I haven’t been the silent man since his second visit. I wonder if he is still alive. I wonder why he didn’t speak. I think I can still hear him.”

•••

Sitting over a hefty breakfast of bacon, eggs, hash browns and toast at a Corydon Avenue restaurant, Craton is asked whether he can compare the pain experienced by elite athletes to the suffering found among the homeless.

“When I sit across the table from an athlete or just a person who has arthritis, I can completely empathize with them, because I’ve had lots of pain myself,” says the doctor, a football and basketball star in his youth who later became an endurance athlete, competing in marathons and triathlons.

“But when I sit across the table from a person whose whole life has been filled with pain and sadness and addiction and abandonment, and on top of that they are homeless and on top of that they have pain, you just marvel at how they are putting one foot in front of the other. How are they doing that? I don’t marvel at that with athletes. I get it.”

When his faith led him to volunteer at the newly-opened Saul Sair Health Centre at Siloam Mission 10 years ago, the six-foot-three MD began keeping track of his experiences. Then, one day, a government agency invited him to give a pep talk about serving clients and serving the community.

“I told the story about the blind patient who had his hearing aids stolen and the reaction was really strong. That story really resonated with people, so I started writing down more of the experiences at Siloam that were like that, and before I knew it, I had 30 or 40 of them.”

•••

“Kindness is a key. It opens hearts hardened by violence, minds shut by pain and spirits bound by condemnation.”

In the second chapter, Craton recalls a day when his then-20-year-old niece, Rachel, was volunteering in the clinic. “Our last patient of the morning was a blind Métis man named Sam,” he writes. “He was in his early twenties and required a guide to help him make his way from the reception area to the examination room.” It turned out Sam was seeking medication to help regulate his sleep cycle, but his problems went much deeper.

“Sam told us that he was regularly bullied and beaten,” the doctor writes. “He was also hearing-impaired and had had his hearing aids stolen during a recent mugging on the streets of Winnipeg. This made his sight-impaired world nearly impossible to navigate. He had no money and no chance of getting new hearing aids.”

On top of that, the blind patient had a painful, swollen big toe, his sock stuck to the skin, glued down by pus and dried blood. “We cleansed Sam’s foot with saline and gauze. This foot-cleaning ritual is common at the mission clinic, as homeless people’s feet are jeopardized by poorly fitting shoes, damp socks and days spent walking to keep warm.

“I try to view the act of washing a homeless person’s feet in the context of Jesus washing his disciples’ feet. For me, this changes the experience from something clinical to something sacred.”

As his toe was treated, Sam confided “no one had ever treated him with such kindness.” Before he left with tears streaming down his face, shelter staff made some calls and a local audiology clinic agreed to give Sam two brand-new hearing aids.

•••

It was his Christian faith that eventually led the sports medicine doctor to begin serving at a clinic for the homeless.

“There’s this passage in the Gospel of Matthew, Matthew 25, where Jesus says if you serve these people who are in jail, who are naked, who are hungry, who are homeless, you are actually serving me. I marvelled at that and it was always in the back of my mind,” he says between gulps of coffee.

“When the Siloam clinic was announced, I thought, ‘Man, I think I’m supposed to be doing that.'”

Ten years later, it’s a decision he doesn’t regret. “I think about this a lot, why I like working there so much, and why it’s so much more enjoyable practising medicine when you’re not getting paid,” he says. “There’s something very pure about that work. Why can’t I feel like that at my clinic? I try to bring the same things to my clinic. But when you’re not getting paid, it carries a different feeling.”

•••

“I am the prodigal son every time I search for unconditional love where it cannot be found.”

This is the story Craton shares at public readings. It’s about a quiet young man he calls Jadon, who arrived at the clinic “in traditional gang-banger attire: black hoodie, baggy black sweats, and a black toque.” He was Caucasian, in his early twenties, roughly six-foot-six, with long limbs and a steely glare. He wanted one thing: burn cream.

“I asked him to show me his burn and he slowly rose from his chair and began to remove his hoodie,” the doctor recounts in Chapter 6. “I was speechless when I saw his torso. He had widespread partial and full-thickness burns over his entire chest and abdomen. A red mass of angry scale and healing skin grafts gave the impression of a badly traumatized reptile… I tried to conceal my reaction but I was dumbstruck by the worst burn I had ever seen.

“How did this happen? Jadon reluctantly told me he was the victim of attempted murder. Some bad actors had tried to kill him by trapping him in a burning building.”

The doctor from the suburbs gently massaged burn cream into the man’s damaged skin. “He reminded me of my son,” Craton confided over breakfast. “With my hands I was rubbing cream on his chest. I was able to bring him some relief. It was a sense of the beauty of being a physician and touching people only trying to help. His burns were overwhelming.

“Him searching for love from a gang connection and the drug world and it led nowhere good; it ultimately led to him being almost burned to death.”

•••

It’s impossible for those of us living comfortably in the suburbs to relate to the anguish and pain experienced by people living on inner-city streets.

But Craton hopes his book goes at least a little ways towards bridging that gap by giving readers a small glimpse into the safe harbour provided at the shelter.

Where to get the book

Dr. Neil Craton’s book, Wisdom from the Homeless, is available in both hard and soft cover. It can be found at McNally Robinson Booksellers, Performance Healthware on Meadowood Drive, and online at Amazon.ca. All the proceeds go to support Siloam Mission.

“It kind of gives you the sense of a day in the clinic…. It’s really nice to reflect on the cases you’ve seen and think about what they’ve taught you. I don’t think we do that enough in medicine. It’s just, ‘I gotta go to the next case, gotta go to the next case.’ There’s more patients than there is time.”

One patient was a person from Craton’s past, his teenage bully who, now years later, taught him a lesson about forgiveness when he came into the clinic.

“Here’s this guy and he caused me a whole bunch of grief when I was a kid, and now he’s homeless and looks like a little old man. He looked 70, 75, walking with a cane.”

It’s that encounter and hundreds more that underscores the message he wants to share.

“The homeless are real people, and mental illness and addictions account for almost all of them. Our society has basically chosen to allow these things to go on, without adequate resources. While rescue missions do amazing work, we can do way better… way better. How do you end homelessness? Give people a home. It’s just like that.”

doug.speirs@freepress.mb.ca

Doug has held almost every job at the newspaper — reporter, city editor, night editor, tour guide, hand model — and his colleagues are confident he’ll eventually find something he is good at.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.