Browaty-led bullying won the Portage and Main battle, but the war will rage on

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/10/2018 (2606 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There was nothing ambiguous about this result.

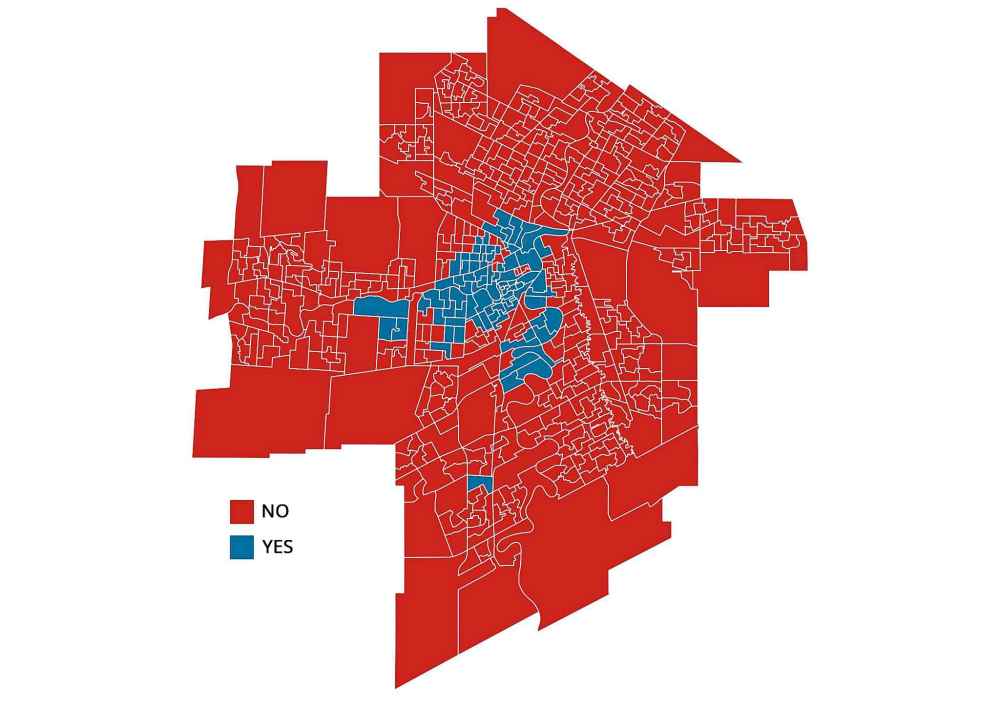

In a plebiscite held in conjunction with Wednesday’s civic election, Winnipeggers sounded a resounding No to the idea of opening Portage and Main to pedestrian traffic. The final vote tally wasn’t close, with the No side enjoying a nearly 2-1 margin over those citizens who wanted pedestrians to stroll street level at the famed intersection

But even as the result of the plebiscite left no room for doubt, that does not mean the future of this intersection is settled. Far from it.

For example, the ballot proposition did nothing prescriptive for the infrastructure challenges at the intersection, largely due to its slowly decaying underground concourse.

As the Free Press reported during the campaign, the city is facing a liability of untold millions of dollars to repair the ceiling of the underground concourse. At more than 40 years old, the waterproofing membrane that separates the concrete road from the concourse ceiling is believed to be failing in many areas, leading to leaks and the erosion of structural elements of the underground.

Significant work, most of it performed above ground, will have to be done to restore or perhaps replace that membrane. Ironically, that work will likely require the removal of the pedestrian barriers that the No forces fought so valiantly to save.

How much will all this cost and how long will it take to complete repairs? Nobody knows because engineering work that would have assessed the size of the problem was not completed in time for the election. Private landowners who own and maintain sections of the outer portion of the concourse have already poked around and found the membrane to have completely disintegrated.

A briefing Thursday by the city planning department was not able to explain whether city-owned portions of the concourse face the same problem.

Planning officials say they won’t know for sure if the membrane needs to be replaced until an engineering study is done. The officials conceded, however, that the underlying concrete in the intersection is 40 years old — very near the end of the lifespan for most concrete roadways — and anything is possible.

However, the future of the intersection’s infrastructure — above and below grade — is hardly the only lingering concern from this plebiscite result.

In a word, the entire decision to throw the Portage and Main question into the election was a manipulation of democracy.

Many people believe that ballot propositions offer rare opportunities for a more direct line between voters and actual policy-makers. Perhaps, but only if the people voting are fully informed about the issues at stake.

In this instance, voters did not have a complete picture of the costs of reopening the intersection. An engineering study that attempted to capture all of the costs did not, for example, consider the concourse repairs and the accompanying above-ground disruption to infrastructure and traffic.

This means the issue of cost of reopening the intersection was completely, irresponsibly misrepresented to voters during the campaign. Lay the blame at the feet of Coun. Jeff Browaty, who introduced the idea of the plebiscite knowing full well that voters would not have a complete picture of the challenges facing this intersection.

Browaty had to know that the city had yet to complete an engineering study on the extent of water damage to the concourse ceiling.

Spend a few minutes debating Portage and Main with Browaty, and you will instantly find out he has encyclopedic knowledge of this file, and a policy wonk’s grasp of the process. It is simply impossible to believe that when he proposed the plebiscite, he did not know that voters were being denied some critical details.

And that brings us to the other major consequence of this plebiscite: a deeper divide between urban and suburban citizens.

As is the case with many big cities, Winnipeg city hall is a battleground where councillors representing older, core neighbourhoods fight with councillors representing newer, more affluent suburbs over infrastructure investments. While the core pursues things such as community redevelopment, affordable housing and renewal and better public transit, the suburbs are looking for new recreational assets and longer, wider roads with more underpasses and overpasses.

At first blush, it seems like a fair fight, but it’s not. Suburban wards have much higher voter turnout. As a result, city council tends to defer to suburban priorities. Now, take that scenario and apply it to a single-question ballot proposition on Portage and Main. It wasn’t hard to see how it was going to turn out.

The people who live in and near the downtown, and those who own businesses and land in the core, overwhelmingly supported the return of pedestrians. Unfortunately, greater numbers of voters from outlying areas eclipsed the desires of downtown folk.

In this instance, the plebiscite was the equivalent of electoral bullying, a tyranny exacted by the suburban majority over the wishes of a core-area minority that has much more affinity for, and involvement in, the intersection and the downtown of the city. Voting patterns clearly showed that the longer voters had to commute, the more likely they were to vote no.

That raw reality made this plebiscite the political equivalent of a suicide mission.

Browaty and other suburban councillors may be relishing their victory now, but it will be interesting to see how Yes supporters on council, including Mayor Brian Bowman, start to view expensive infrastructure that is specific to suburban ridings.

If those members of council become a bit less sympathetic to suburban projects, it wouldn’t be revenge, per se. Instead, it would be a reminder that what’s good for the downtown goose may ultimately come back to haunt the suburban gander.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.