Little impact expected from new provincial party

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/07/2022 (1239 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There are moments in the political evolution of a nation or region when a new movement — a breakaway ideological faction, or perhaps a new political party — transforms the electoral landscape and forever alters the way governments are chosen and legislative processes proceed.

The formation of the Parti Québécois in 1968, by merging Quebec’s Liberal Party with René Lévesque’s Mouvement Souveraineté-Association and the right-wing populist Ralliement National, galvanized separatist support and eventually led to the election of a PQ government in 1976 and, under premier Jacques Parizeau, forced the 1995 Quebec sovereignty referendum that came within a percentage point of fracturing the nation.

The 1987 launch of the Reform Party of Canada gave voice to the fury of westerners fed up with being ignored by central Canada’s (Ontario/Quebec) power brokers, and its rise was instrumental in the 1993 electoral implosion of the federal Progressive Conservative party, which fell from 151 seats to just two.

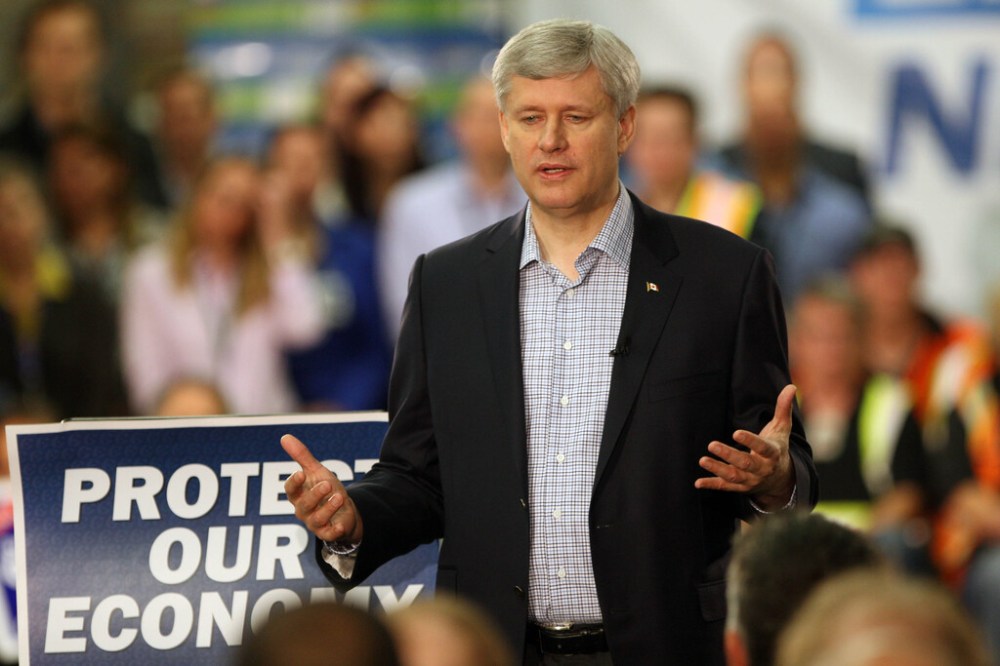

Later rebranded as the Canadian Alliance, the party merged with the slightly revitalized PCs in 2003 to become the Conservative Party of Canada, which seized power in 2006 and, under the leadership of prime minister Stephen Harper, maintained control of Parliament for almost a decade.

South of the border, the rise of Donald Trump redefined the so-called Party of Lincoln, turning it from the small-“c” conservative option in America’s two-party system into a refuge for angry white men, internet-misinformed conspiracy theorists and overzealous cult-of-personality disciples. While it remains the Republican Party by name, this version would not be recognizable to one of the GOP’s most revered conservative leaders, Ronald Reagan.

Seismic shifts all, forever altering the political trajectory of their countries.

The launch of the Keystone Party of Manitoba is unlikely to be one of those moments.

The announcement last week that the fledgling right-of-centre party has met the requirements for political-party status and is readying to run candidates in next year’s provincial election may have raised a few eyebrows locally, but the reality of Manitoba politics is that this refuge for variously aggrieved right-leaning rebels stands very little chance of shaking things up in a province whose electoral battle lines are indelibly drawn, both ideologically and geographically.

The new party’s leader, Manitou-area grain farmer Kevin Friesen, promised an alternative in which the selection of candidates and decision-making on major policy issues will be controlled by “you, the grassroots of Manitoba.” Official policy positions on such issues as immigration, climate change and reconciliation will not be released until individual constituency associations have a chance to discuss them and bring ideas forward for presentation to voters.

Mr. Friesen’s address did, however, include a strong undercurrent of “freedom,” rooted in the anger and division related to the business shutdowns, mask mandates and vaccination requirements imposed during the COVID-19 response.

As a result, it bears noteworthy ideological similarity to the federal People’s Party of Canada. And it’s almost certain to experience a nearly identical fate when Manitobans go to the polls: noticeable support in a few rural ridings in which anti-restriction, anti-vax sentiment runs deep, but not enough to actually win seats in the legislature, and distant also-ran status virtually everywhere else.

If current polling trends hold, the Progressive Conservatives will hold strong in rural/southern Manitoba, and the NDP will likely regain control of Winnipeg while solidifying its hold on the north. The Keystone Party will be on the ballot, but will be insignificant in the campaign conversation and election-night tabulation.

Purveyors of populist politics in this province will have to look elsewhere for their watershed moment.