Sagkeeng woman a ‘thriver,’ not a survivor First court date of residential school priest accused of abuse brings out community

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/07/2022 (1236 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

POWERVIEW — Victoria McIntosh walked into court carrying the tiny coat over her arm, gently folded. It was the coat her grandmother Pauline Guimond had made for her. The coat she wore on her first morning of day school; the cream woolen coat with love in each of the neat stitches and a jaunty plaid trim on the collar.

And it was the same coat that the nun, on that first day of school nearly six decades ago, ripped off and threw at McIntosh’s mother. The nun hissed a word in French that McIntosh didn’t yet know, but she came to know it soon after. She came to know it was how the priests and nuns who ran the school thought of her, and her Anishinaabe people.

“Sauvage.”

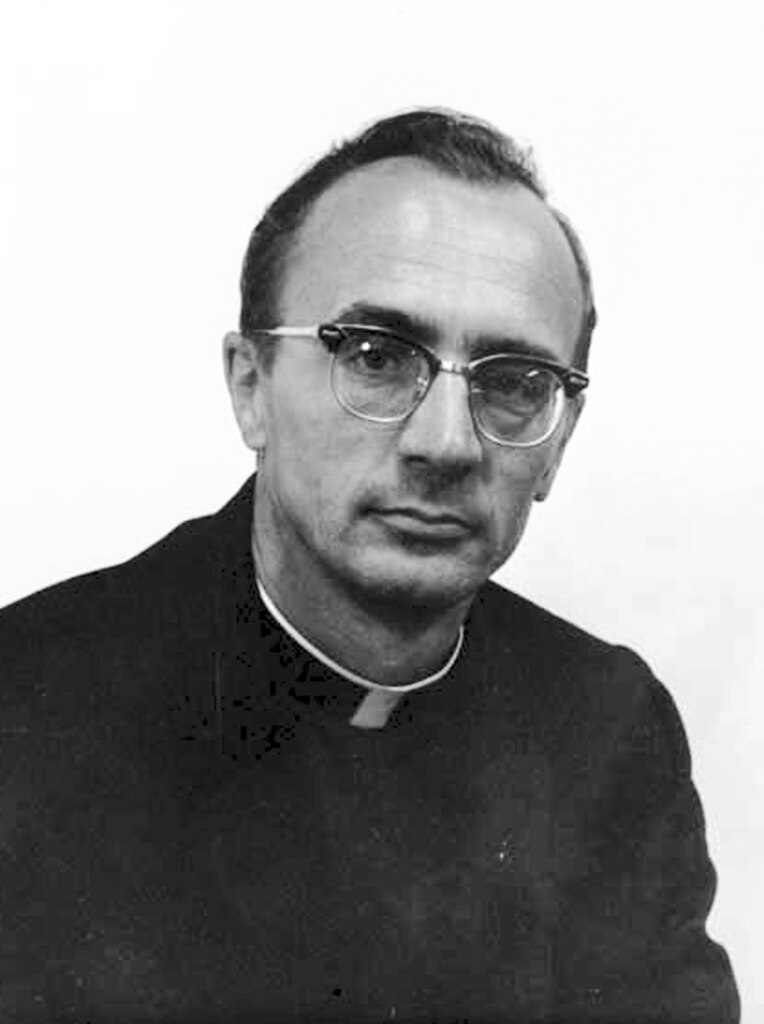

It’s been decades since then. McIntosh isn’t a little girl anymore. At 63, she is a mother, a grandmother, a teacher. She has a voice now, and she’s using it. She used it to tell RCMP that a Catholic priest at the Fort Alexander Residential School had sexually abused her when she was just 10 years old. Last month, 92-year-old Arthur Masse was charged with indecent assault.

McIntosh is also using her voice to assert the truth of who she is, and who her people are. For instance, she doesn’t like to call herself a “survivor,” but rather a “thriver.” And she is an anishinaabekwe, an Ojibwa woman from Sagkeeng First Nation, born to a long line of wise and loving people. Not the cruel words the nuns and priests called her.

“I’m not a savage,” she said as she spoke to reporters outside the local Royal Canadian Legion, where the first hearing in the Masse case was held Wednesday. “Neither are my people. We’re a kind, giving people, and we’d help out anybody that comes to us. And that’s what my message is today.”

“I’m not a savage… Neither are my people. We’re a kind, giving people, and we’d help out anybody that comes to us. And that’s what my message is today.” – Victoria McIntosh

That generosity of spirit is one truth of this story. It’s a truth as central to the case as whatever happens in court, as essential to understanding it as the abuse McIntosh reported. The schools are gone now, but McIntosh and others who lived in them are speaking. They endured, and so did the love they carry, and that love shone a light on Wednesday’s proceedings.

It shone in the sweet trails of smoke that wafted outside the legion, where McIntosh’s supporters sang and held a smudge ceremony. It shone inside the building, in a makeshift courtroom lined by glossy posters of vintage fighter planes and a long row of old bowling trophies.

As she waited for the hearing to begin, McIntosh sat quiet and proud, cradling the wool coat in her lap. Joseph, her eight-year-old grandson named for her grandfather, was beside her; Allen, her husband of 34 years, sat just behind. The other chairs in the room were filled by supporters and members of Sagkeeng First Nation, some with their own stories to tell.

The hearing was brief, the matter remanded to Aug. 17. Among a number of things that have to be sorted out first, court heard, is which language Masse will request for the proceedings, French or English. It’s a choice that children in residential schools were never given. Their languages were taken from them; the priests decreed it.

Masse wasn’t in court. It’s not clear what his physical condition is now, or when he will make an appearance. If he had cared enough, McIntosh told reporters later, he would have found a way. But one day, she will see him for the first time since she was a child, she says. She plans to follow the case every step of the way.

She has to do it, she said, not just for herself, but for her mother and her grandparents, who lived through residential school before her. In that way, a reporter said, this moment is less about Masse; it’s about McIntosh and her journey. It’s about the tides of history that once threatened to drown her voice, but never could wash it away. McIntosh nodded.

“All that shame, all that anger, everything I felt, it’s going to go with him,” she said. “I didn’t deserve that at 10 years old. No child does. He stepped over the line. He violated. Some of us are going to speak out, and I’m glad I did. Even though it was a hard journey in the last few years, I’m not going to give up.”

“All that shame, all that anger, everything I felt, it’s going to go with him… I didn’t deserve that at 10 years old. No child does.” – Victoria McIntosh

After the few minutes of the hearing whisked by, there was time to gather. Outside, as the heat of July settled over the day, Sagkeeng members glided through the parking lot, shaking journalists’ hands and offering bottles of water. Inside court, something important was happening, a conversation that showed the vastness of that generous spirit.

It was then that Sagkeeng Chief Derrick Henderson approached the Crown attorney and made a formal request: if Masse is found guilty, then Sagkeeng wishes to hold a sentencing circle in their community. It would be a way to bring healing to the First Nation on which the residential school was located, a way of inviting pain to be reconciled through love.

“We invite him,” McIntosh said, echoing Henderson’s call. “We open the doors. If this is agreed, let’s do this thing. Let’s begin again, let’s begin in a healthy way, and in those virtues we hold as people.”

Before leaving the courtroom, the group got together and posed for a photo. As they got into position, McIntosh’s grandson held up the coat that she had been carrying, the one her grandmother had made, the one a nun once threw away. Then, the boy turned to the chief, and excitedly announced how few days remained until his ninth birthday in August.

“Honestly, I’m excited,” he told Chief Henderson, who couldn’t help but chuckle.

McIntosh smiled to think of how excited her grandson is about his birthday. That’s another thing about the meaning of this journey: when she was in residential school, she didn’t know when her birthday was. “These are the kind of things we didn’t talk about,” she said. “Nothing was celebrated. Christmastime was a chore.”

Later, after she left the walls that closed in on that harsh world, she began to celebrate her birthday again. It’s in April. Now, five decades and two generations of young Anishinaabe people later, she speaks in invitation to a world in which Indigenous children will never again have their joy stolen, and never again be told they are anything other than who they are.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.