Challenging experience of challenging way we think

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/05/2022 (1287 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This is your brain on racism: rampant, deeply seeded biases that lead to dangerous assumptions. Unconscious cognitive mechanisms. Good old-fashioned ignorance.

These are not only the building blocks of systemic racism, they are inherent byproducts of the human condition. In other words, although racism is abhorrent, the biases that lead to racism can be explained by examining the ways in which human brains process information.

Why, you may ask, is that important?

There is a strong and well-grounded theory the more we know about how our brain works, and the biases we all possess, the more likely we can shed racist behaviours and mindsets.

It’s the working theory behind a new exhibit at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg.

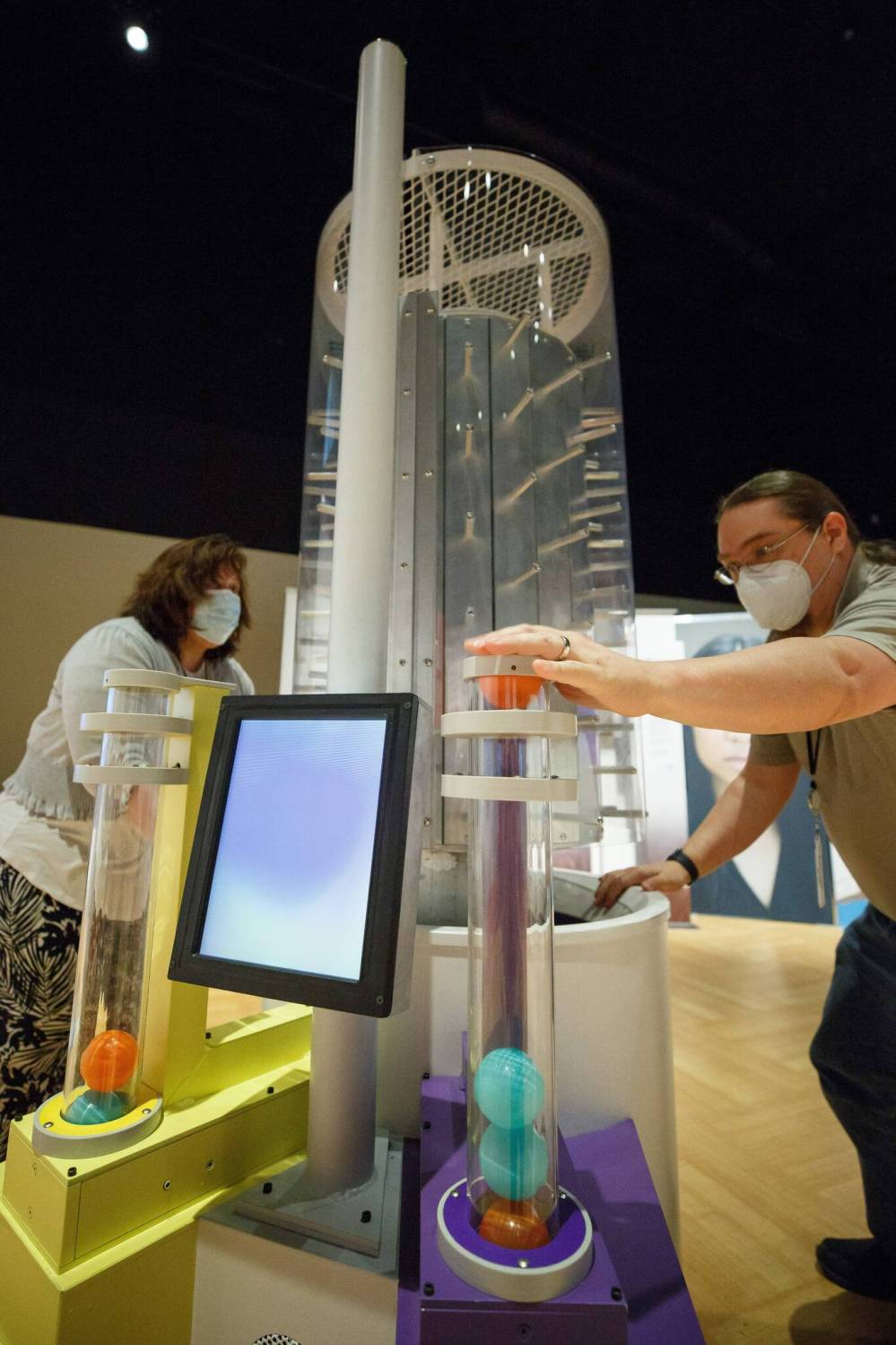

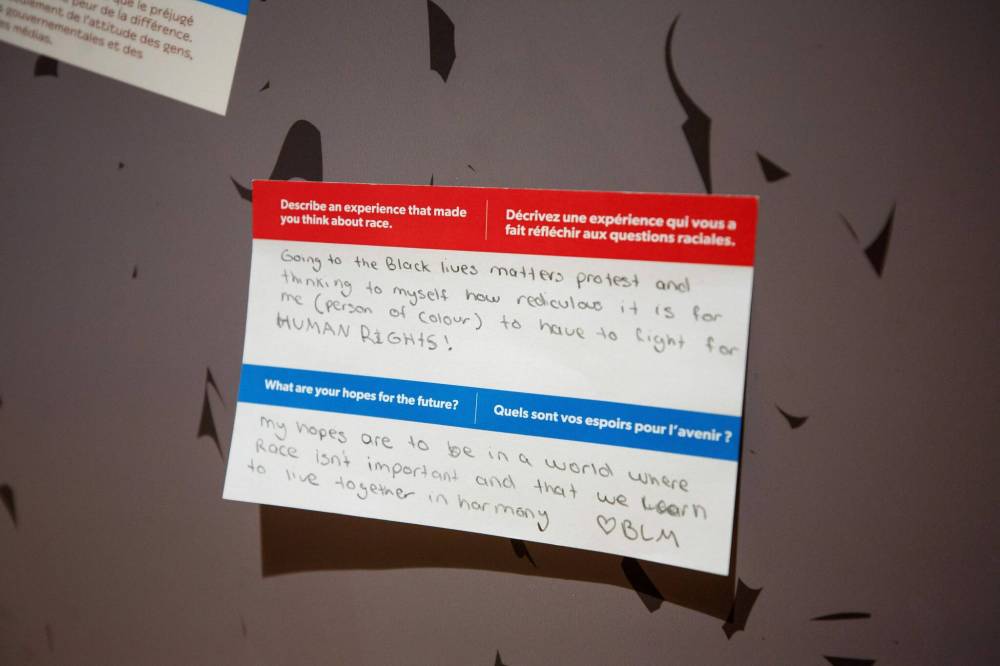

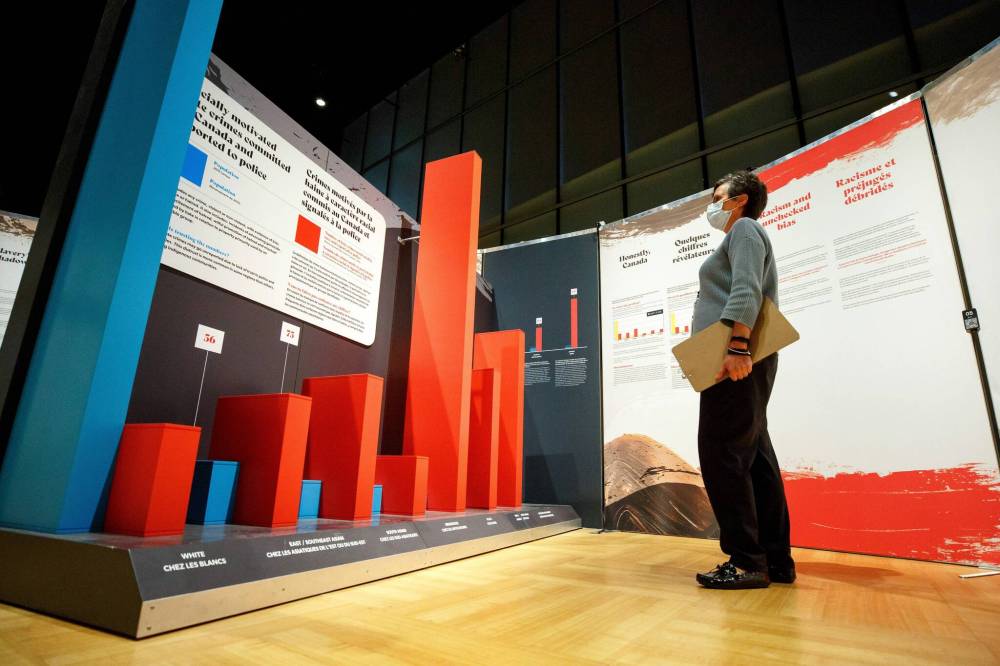

Behind Racism: Challenging the Way We Think is a the result of a collaboration between the Canadian Race Relations Foundation and the Ontario Science Centre. The touring exhibit uses interactive games, videos, 3D models and personal testimonies from Canadians who have experienced racism first hand to provide insight into how we latch on to racist ideas.

Taken together, the exhibit is clever, deeply fascinating — largely because of its reliance on science — and (particularly when you sample the video testimonials) quite emotional. But there are two bigger questions lingering over the exhibit.

Will it actually change the way people think? And if there is potential to do that, will it reach the people who really need to confront their biases and think differently?

“When you’re trying to change the way people think, one exhibit isn’t going to do the entire job,” said Isha Khan, museum chief executive officer. “But it is one more step in the right direction.”

In a conversation shortly after touring the exhibit — which the museum has made available to the public free of charge — Khan acknowledged one of the questions/concerns surrounding the CMHR in all its programming is whether it will attract and inform people who most need enlightenment on the issue.

Make no mistake about it: the CMHR was designed to challenge assumptions. Whether it is homophobia, genocide or systemic racism, there is already a wealth of content that both informs and provokes. Even the most open-minded and progressive among us will find something in the museum they didn’t know about our capacity for inhumanity.

But it’s always been unclear whether the CMHR is attracting people who largely already respect human rights or people who dispute the importance of human rights?

“It’s an iterative process to be sure,” Khan noted.

However, can that iterative process decode and defuse racism, an insidious and pervasive condition? This could be among the most important and challenging tasks the museum has ever taken on.

The exhibit leans heavily on decades of research into brain function that acknowledges the racist mind believes races are inherently different from one another in all respects: mentally, physically, genetically, intellectually. A racist mind rationalizes the challenges faced by a racialized group on the basis they do not work hard enough or care enough for each other or have the drive and passion to live a better life.

This is where brain function comes in. The racist mind takes the consequences of systemic racism — poverty, unequal access to opportunity, social dysfunction — and celebrates them as causes.

The CMHR exhibit is built on the premise by understanding how human brains adopt and process racist thinking, we can learn to be more tolerant and understanding.

Briefly, the theory is inherent brain functions help to create biases about people of different races, genders, sexual orientations or gender. Once embedded, our brains tend to view and interpret everything around us within the context of those biases.

In other words, we use our observations to re-enforce a bias until it becomes a core belief.

Indigenous people are lazy. Black people are better athletes. Asian people are smarter. White men are best equipped to lead.

Most fair-minded people know — or should know — these assumptions are deeply flawed. So why do they persist? In short, we are victims of tradition and repetition. We’ve spent so many years re-enforcing our biases, they become self-perpetuating.

Consider the hiring process.

Based on the prevalent methodology of our times, most employers require applicants to have “previous experience,” typically by having held a nearly identical position somewhere else. That bias — previous job experience — means if a particular job or profession is dominated by white men, then it’s almost certain a white man will be hired every time there is a new job opening.

To the racist mind, the evidence is compelling: white men dominate the ranks of certain professions (politics, for example), so clearly people of colour or women or women of colour, are simply ill-equipped for the job. And so it goes.

In this context, the mission of the CMHR exhibit becomes quite courageous. But does it stand a chance of success?

With all of the recent acts of hate-fuelled violence showing the extent to which the racist mind will enforce its view of the world, it would be easy for us to throw our hands up and give in to despondency.

Thankfully, the CMHR has decided to take another approach.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, May 31, 2022 7:42 AM CDT: Corrects typo