Raw realities of wrongfully convicted leave lasting ache

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/05/2022 (1303 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was mid-morning on Sunday when a friend called to tell me David Milgaard was dead.

Milgaard had been camping with his daughter over the weekend when he started to feel ill. Late Saturday, he went to hospital. By early Sunday morning, he had been diagnosed with pneumonia. A few hours after that, he was gone.

As I reeled from the news, I felt an incredible ache in my heart.

I got to know David in the late 1980s, long before he became arguably the country’s most famous victim of wrongful conviction. Back then, he was a quirky and earnest 30-something life prisoner with an fidgety disposition and an incredible story to tell.

I tried my best to tell that story but in the process, I was exposed to the raw reality of his life: the incredible mental and physical burden that comes with being a victim of a wrongful conviction.

It wasn’t just that they took away his freedom. It wasn’t just the mental and physical torture that came with being in the prison system. It was being told he had done this horrible thing when he knew, deep in his heart, he had not.

It wasn’t just that they took away his freedom… It was being told he had done this horrible thing when he knew, deep in his heart, he had not.

As I thought back to those years, the memories came flooding back. My first meeting with David at Stony Mountain Institution. The phone calls, at all times of the day and night, when he would tell me to keep writing stories even though each new dispatch usually resulted in a beating from other inmates who came to despise his notoriety and his unwillingness to admit guilt.

And then it hit me: this was not the first time I felt this ache.

The first time was April 16, 1992. Milgaard, wrongfully imprisoned for 23 years for the murder of a Saskatoon nursing assistant, had just strolled out of the front doors of the penitentiary north of Winnipeg to face an angry, slate-grey spring sky and a throng of journalists.

Just two days earlier, the Supreme Court quashed his 1970 conviction and ordered a new trial. With new evidence showing prosecutors and police had suppressed the existence of another suspect, Saskatchewan justice officials declined to prosecute a second time.

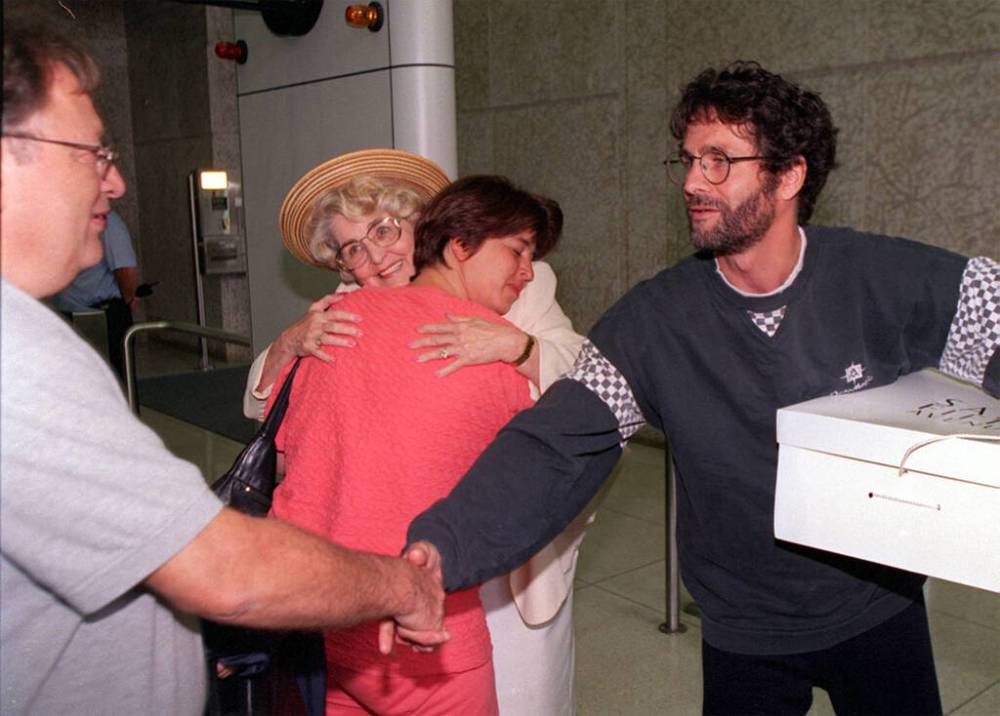

Freedom now a reality, Milgaard seemed unusually calm. Holding hands with his sisters Susan and Maureen, he strolled out of the prison’s front doors wearing a black baseball cap, with head phones slung around his neck and a Walkman stuffed in the breast pocket of his shirt.

He did not make eye contact. He just walked slowly, sisters in tow, as the crush of cameras and microphones swallowed him whole.

Eventually, he was led to a waiting car where one of his lawyers, Hersh Wolch, was standing with a huge grin on his face. As Milgaard got close, Wolch handed him a brand new Manitoba birth certificate dated April 16, 1992. Wolch then said, “this is the day when the rest of your life begins.”

Milgaard looked at the birth certificate and smiled. He turned to the cameras and made the only statement he would make that morning.

“It’s good to be out forever. I’m just going home.”

“It’s good to be out forever. I’m just going home.” – David Milgaard

As the car pulled away, I felt my legs start to shake and my eyes fill with tears. Suddenly, there was a hand on my shoulder. Paul Henderson, a former Pulitzer prize winning journalist turned private investigator from Seattle was standing right behind me, his own eyes full to the brim.

Henderson, who had helped free a dozen other wrongfully convicted men, had done as much as anyone to get Milgaard out of jail. Working for New Jersey-based Centurion Ministries, Henderson had tracked down new evidence that proved another man had killed the nursing assistant.

His smoke-ravaged voice shaking, Henderson told me that no matter how many times he had watched an innocent person walk out of prison, it always produced the same mixed feeling.

Happiness wrapped tightly in heartbreak.

My head wanted to celebrate Milgaard’s release; my heart was weighed down with the knowledge that even if this was the first day of a new life, it was likely to be a very difficult life.

Over the next three decades, there were highs and lows. Milgaard would marry and have two children. He would separate from his wife. He had a couple of very minor brushes with the law. He battled the demons that attached themselves to him over the 23 hard years he spent in prison.

Over the next three decades, there were highs and lows. Milgaard would marry and have two children… He battled the demons that attached themselves to him over the 23 hard years he spent in prison.

But whatever pain he was carrying, he never stopped doing interviews, speeches and appearances, pleading with the stewards of the justice system to be better. To find a way to prevent miscarriages of justice like his from ravaging the life of others.

Some of those stewards listened to him. The federal Liberal government has promised to bring in a truly independent commission to review cases of wrongful conviction, largely because of the tireless advocacy that David and his late mother Joyce made a part of their life post-release.

It isn’t done it yet. But it’s perilously close.

David was planning to step back from his advocacy work and now, he won’t be around to see that which he fought so ferociously to accomplish.

But if the commission is created, you can be sure that somewhere, somehow, David will be finally at peace.

dan.lett@winnipegfreepress.com

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.