Expect inflation fight to be bruising… once Ottawa rings in

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/04/2022 (1327 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If February’s soaring inflation rate didn’t catch the attention of the federal government when it unveiled its budget earlier this month, maybe the latest figures will.

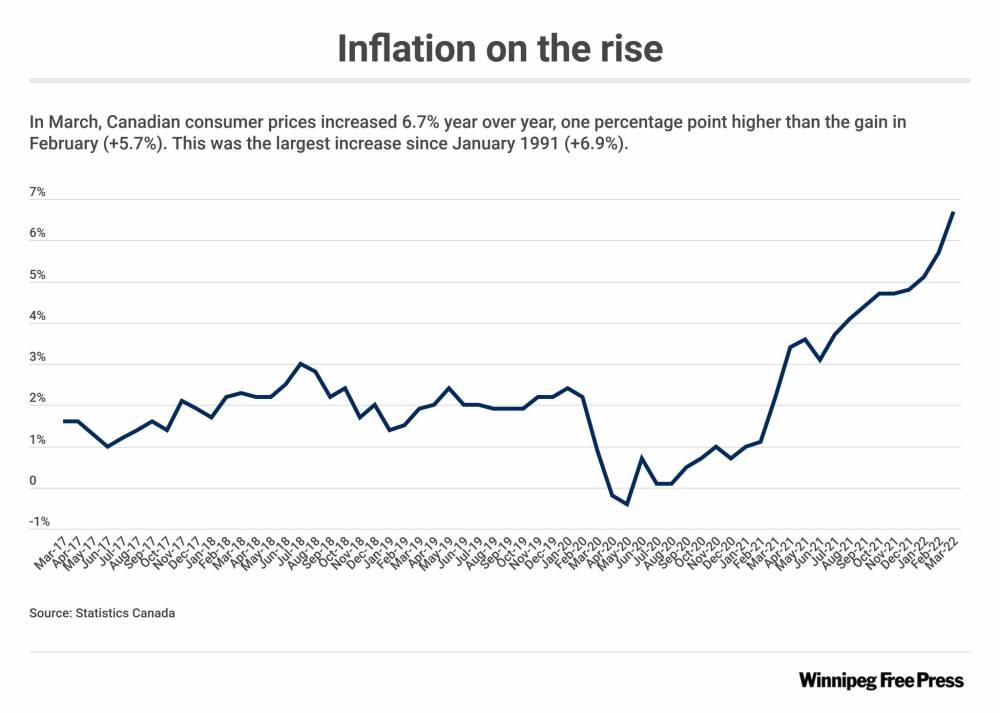

Canada’s inflation rate hit an eye-popping 6.7 per cent in March, compared with the same month last year. It’s a full percentage point higher than February’s year-over-year rate and the highest since January 1991. Month to month (February to March), it grew 1.4 per cent.

It was even higher in Manitoba, where price growth was 7.4 per cent.

The rates are worse than economists expected and are growing at an alarming rate. Inflation is by far the single biggest threat to Canada’s economy right now.

Price increases hit low-income Canadians the hardest, especially since some of the biggest jumps are for essential goods, such as food.

Overall, grocery items rose 8.7 per cent. Breakfast cereal is up 12.3 per cent and pasta products increased 17.8 per cent. There’s not a lot of wiggle room for most low-income households to absorb those increases.

The problem with inflation is governments have few tools to fight it. Price and wage controls, tried in the late 1970s with little success, are not even on the table.

Legislating prices and wages has the potential to keep inflation in check in the short term. However, it’s a draconian measure fraught with pitfalls and unintended consequences, including supply shortages and latent inflation that bounces back once controls are lifted.

So what’s left for government? Not much.

The only proven tool is the one that ultimately wrestled inflation to the ground in the 1980s: high interest rates.

It’s a blunt instrument that can cause a lot of pain in the short term, depending how much oxygen needs to be sucked out of the economy. Boosting interest rates (along with a restricted money supply) slows economic growth and discourages people and businesses from spending. Over time, weakened demand brings prices down.

It’s a crude policy that usually results in job losses, business failures and even recession, but it works. No one has come up with a better solution.

The hope is interest rates, which are still historically low, won’t have to climb to double digits (like they did in the 1980s) to beat inflation. The Bank of Canada, which raised its key overnight rate by a half-point last week, is expected to jack up rates again in June (probably by another half-point) and will likely do so several more times over the next 12 months.

Inflation is complicated. There are many factors driving it, including soaring oil prices, persistent global supply chain disruptions, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s possible four or five rate increases, along with supply chain improvements, could bring inflation under control without inducing a recession.

No one knows.

It may not return to the Bank of Canada’s inflation target range of one to three per cent anytime soon. But if the consumer price index drops two or three points and stabilizes, it would be considered a victory.

In the meantime, there are factors that can exacerbate inflation, including broad-based, heavy spending by governments — the kind Canadians saw from the federal government in its 2022 budget.

The budget expands program spending by 25 per cent compared with 2019-20 (the year before the COVID-19 pandemic hit). The projected deficit is double what it was three years ago, and there are still no plans to balance the books.

It’s a high-spending budget that will contribute to inflation and undermine the efforts of the Bank of Canada. It could get worse if the federal Liberals spend beyond budgeted amounts to satisfy their NDP partners in Parliament.

There is one area of new spending Ottawa should consider: providing targeted supports to people hardest hit by soaring inflation.

However, there is one area of new spending Ottawa should consider: providing targeted supports to people hardest hit by soaring inflation.

It could be achieved through existing mechanisms, such as an enhanced GST rebate. The increased costs could be paid for by cutting spending in other areas, such as the $408 million in the budget to promote official languages, $84 million over five years to increase the number of judges across the country, and billions more in planned “stimulative” spending scattered indiscriminately throughout the economy.

Canada is still nowhere near the 12 per cent inflation rate it saw in the early 1980s. But it could hit double digits quickly if governments don’t start taking it seriously.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.