Vaccine justice for all Ma Mawi’s vaccine clinic is about much more than putting needles into arms

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/01/2022 (1411 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The first thing Charmaine Delaronde does when she gets to work, the first thing she has to do before anything else, is get the vaccines ready. She reaches into a medical-grade refrigerator and selects the boxes of vials they’ll use that day, each bearing a familiar brand name, either Pfizer or Moderna. Once that’s done, she wheels the cart over to where staff are waiting.

It’s early on a Friday morning. Outside, new snow mixed with old whips across McGregor Street, and the few people trudging down the sidewalk lower their shoulders against the wicked wind. But inside the gymnasium at Win Gardner Place, which the Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Urban Indigenous Vaccination Centre has called home since April, the atmosphere is peaceful.

In the middle of the room, Delaronde, a public-health nurse and the centre’s clinical lead, stands before the cart, while the other 14 staff working this morning spread out to form a wide circle around her. She lifts a large shell filled with sage and touches it with a flame, letting the fragrant smoke waft over the cart and over each little glass vial.

“Starting out every day on a positive note, looking forward to that connection and that positive message with our community and starting it with ceremony is really crucial.” – Dustin Leach

She is wearing her ribbon skirt, and the earrings her sister beaded for her. Around her neck hangs her Winnipeg Regional Health Authority identification, on a lanyard she made five years ago. It was her very first beading project, using colours she’d received in ceremony; light blue, yellow, white, red. She touches it sometimes as she talks. It’s very special to her, she explains later.

After the vaccines have been smudged, Delaronde turns to the people. She glides around the circle, holding out the shell to each staff member in turn. One by one, they cup their hands and coax the sage smoke over their faces and chests. The only sound in the room is the muffled melody of a classic rock tune, jangling from a radio in the corner.

Once everyone has had their chance to smudge, Dustin Leach makes a joke about that, about being grateful for the music. The staff laugh. Leach is the team lead for the community support side of the centre, overseeing a wide range of resources offered to visitors who come in for their shot; now, he speaks to raise his co-workers’ spirits for the work ahead.

“Let’s have another awesome day together,” he says. “Thanks guys. Miigwech.”

Every morning at the Ma Mawi vaccine centre starts like this. It’s important, Leach says. In Indigenous culture, the smudge offers cleansing, and also protection; and there’s also something sacred about having that quiet time together, before taking their place on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19.

“Starting out every day on a positive note, looking forward to that connection and that positive message with our community and starting it with ceremony is really crucial,” Leach says. “It’s one of the best parts about working in these organizations, is having that medicine around, having everybody from different walks of life be part of that circle.”

What is happening here is about that love, and that care, and that hope. It is also about health justice, and healing.

When COVID-19 came to Manitoba, it hit Indigenous communities hard. Throughout the pandemic, Indigenous folks have suffered both far higher infection rates than white Manitobans, and also more serious outcomes: though just 13 per cent of the population is Indigenous, they accounted for up to 60 per cent of ICU admissions near the peaks of some waves.

By spring 2021, it was also becoming apparent that vaccine uptake in many low-income neighbourhoods was trailing that of wealthier areas. Language barriers, difficulty accessing transportation or child care, lack of safe housing and other issues all contributed to the problem; the answer, vaccine teams hoped, would come through community-based partnerships.

So the idea behind the urban Indigenous vaccination clinics, then — there is another one at 181 Higgins Ave. — was to create a space that would break down any barriers standing between people in the community and the vaccines. Above all, it was to have a space that could meet anyone where they were at, no matter what other challenges they were facing.

It made sense to turn to Ma Mawi. The centre — its full name is Ojibway for “we all work together to help one another” — was already one of the most respected social-service organizations in the North End and beyond, running 50 programs to support youth and families across 11 different sites. Staff there knew their people, and their people trusted them.

Soon, the province approached Delaronde to become the Ma Mawi centre’s clinical lead. She jumped at the offer; she was already familiar with Ma Mawi, having run a North End breastfeeding group out of one of its locations, and the chance to shape a space that would combine culture, community and vaccines gave her a “second wind,” she says.

In a way, her whole life had prepared her for that role. A member of Sapotaweyak Cree Nation, she grew up in Cormorant, a tiny community northeast of The Pas. As a teen, she moved to Cranberry Portage to go to high school, where she stayed in a residence that had an infirmary. She bonded with the nurse there and spent hours learning about the work.

“There are no words to describe how it feels to be able to wear a ribbon skirt to work.” – Charmaine Delaronde

That fascination stayed. After moving to Winnipeg for university, she volunteered at Children’s Hospital, an experience that clinched her decision to become a nurse. She began her career in hospitals, where she cared for many patients with stories much like hers: Indigenous people come from the North, alone, having had to leave home for reasons outside their control.

She loved helping them, which inspired her to follow her heart into community nursing. When the pandemic hit, she was poised to jump onto the front lines. She was the case manager for Manitoba’s second COVID-19 patient, and joined an outreach team that ventured into rundown rooming houses, tracking down contacts, trying to stop the spread of the virus.

Now, she was charged with leading the clinical staff at the Ma Mawi centre. On her first day, she tucked her ribbon skirt — the garment traditionally worn by Indigenous women for ceremony — into her bag. As she prepared for the smudge, she looked up and saw the other Indigenous women on staff wearing their skirts; her heart soared. It felt so empowering.

“There are no words to describe how it feels to be able to wear a ribbon skirt to work,” she says. “It’s a sacred ceremony, but it’s also a way of honouring my culture, and it’s a symbol of resilience. There are days I’ll just wear it to smudge, and there are days I feel like I need a little something to keep me going, and I’ll just wear it all day.”

Culture, community and COVID-19 vaccinations: the formula worked. Since the centre opened in late April, it has administered more than 32,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccine, as well as flu shots and catch-up immunizations for youths who missed their regular shots for hepatitis, meningitis and HPV due to school closures.

No matter what barriers people face, they are welcome at the Ma Mawi centre. Last summer, its mobile team went out to meet some of the city’s most vulnerable residents living on the street. When people arrive at the centre, they are greeted by Ma Mawi staff, who help calm their fears or connect them with any resources they need.

In the hallway, signs affixed to the walls invite visitors to ask about the supports they have available. “Would you like a Ma Mawi wellness helper to check in on you while you wait for your second vaccine?” one reads, offering ongoing contact between doses. “Would you like a medicine bundle?” “Do you need assistance to get home today?”

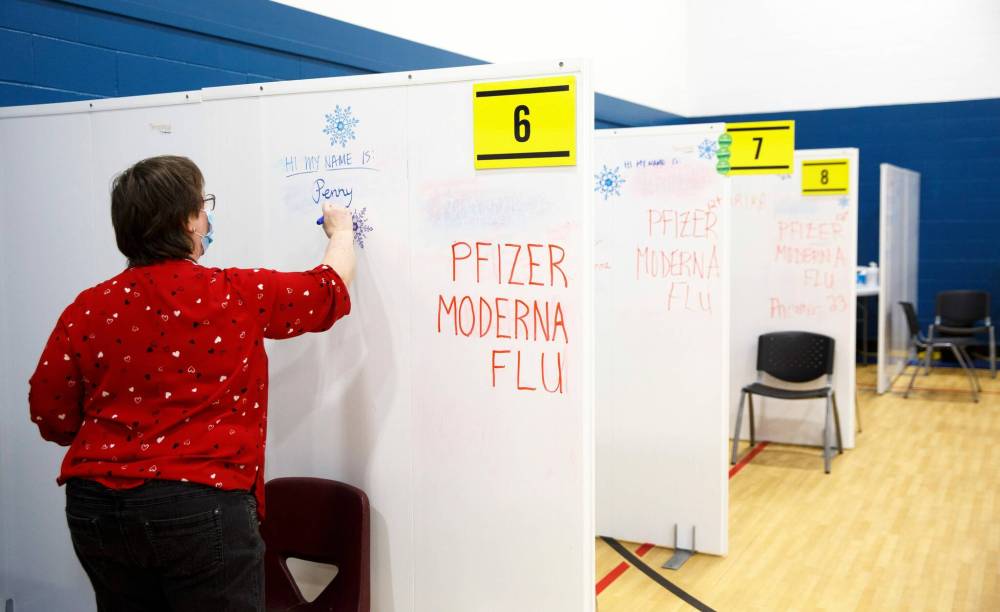

Throughout the space, there are personal touches. When Ma Mawi staff escort people into the gymnasium, they introduce visitors to their immunizer by name and nurses write their names on the white partition walls that provide a little privacy to each station. Right away, that can make the experience feel warm and friendly.

“Hopefully we can just follow that through,” says Irene Paré, one of the immunizers.

Paré joined the team here in June. Now 71, she had tried to retire from her 51-year nursing career in late 2020, but she made it just two weeks before she was already bored out of her mind. By last January, she was back on the job, delivering COVID-19 vaccinations at the RBC supersite, where thousands of people flowed through each week.

She was glad to be a part of the effort, but it wasn’t really her style of nursing. It felt a bit like cattle herding, she says, barely a chance to get the patient’s name and then, bam — give ’em the jab and move on. So when she heard from colleagues that Ma Mawi’s vaccine clinic was “the place to go,” she decided to jump on board.

At Ma Mawi, she found that one-on-one connection with visitors that she craved. There’s time to sit and hear their stories and, in this community, there are many. People roll up their sleeves and pour out their hearts. They tell her about all their struggles and their worries. They tell her about the loved ones they’ve lost to the virus.

“It’s been a bit eye-opening,” she says. “The people, a lot of them are so poor, and their situations are so sad, and they’re still coming in to get the vaccine to help everybody else out.”

She shakes her head, lost in thought. “It’s just… wow. I’m getting a little emotional, just thinking about it.”

The nice thing, she adds, is that she has the ability to help offer some calm. Once, a man sat down and admitted that he was anxious, but he had a child and wanted to get the shot, and since there’s time to be gentle at the Ma Mawi clinic, they sat for a while and just talked. About football, or whatever else came to mind.

”I said, ‘You tell me when you’re ready,’” Paré says. “I’m not forcing this on you.”

When he was ready, she got it done quick. The man was so grateful for her support that when he came back for his second dose, he presented her with a Tim Hortons gift card.

So visitors like that stick in her mind, but to be honest, many of them slip into the familiar rhythm of the work of getting shots in arms. “I had you last time,” clients will happily exclaim, which feels good to hear, but she has administered hundreds of injections since the last time she saw them, so sometimes she doesn’t really remember.

The girl with the blanket, though; that one she will never forget.

It was a day in early December when the girl came in with her support worker. She was in her mid-teens, and she wore a blanket draped over her head so that she couldn’t see anyone, and no one could see her. She settled into the chair where Paré was waiting, and as the nurse prepared the syringe, she could sense the girl’s fear.

“OK, sweetie,” Paré said, willing her voice to be soothing and tender. “I just need you to show me your arm.”

She let Paré lift up her sleeve. Underneath, her arm was so scarred that it was difficult to find a spot to inject the vaccine. The child had been exploited, the nurse realized, her body a map of unspeakable traumas. Paré focused, inserted the needle and then it was over; a quick pinch and done. She heard a quiet voice from under the blanket.

“Thank you,” the girl said. It was all she said.

The girl’s support worker told Paré they would not wait the usual recommended 15 minutes to ensure there hadn’t been an unexpected reaction to the vaccination. That’s OK, Paré told the worker, as long as you stay with her. Then they were gone, off to whatever journey of healing the child had begun. It was a small victory, but at least now she had begun to build some protection against COVID-19.

“She was brave enough to come in, which really impressed me.” – Irene Paré

In the weeks since, Paré and other clinic staff have thought about the girl often. She lingers in their memories as a reminder of who they are there for, and the special place they have created in Manitoba’s vaccine effort. The child couldn’t have managed at the RBC supersite, Paré says, no way. It wouldn’t have been safe for her.

What the girl must have gone through, just to get her vaccine. Still, she found the strength to get there.

“She did, she did,” Paré says, her eyes moistening. “She was brave enough to come in, which really impressed me. And she said ‘thank you.’ She didn’t need to say a word, I wasn’t expecting anything. But she said ‘thank you.’”

•••

In a long room beside the gymnasium, Dustin Leach stands at a table, busily packing crayons and colouring books into bags. Beside him, one of the roughly 25 staff members who work for the centre’s community support team is doing the same thing, but with medicine bundles, filling little baggies with cedar foot soaks, tea bags and a pinch of sage.

This work is just as crucial to how the centre works as the vaccinations are. If the goal is to break down barriers that hold folks back from getting their shots, it means being ready to adapt to their needs. To do that, Leach and his staff take on a variety of roles and rotate through, pitching in with all sorts of things.

For visitors with kids, there are the activity bags Leach is making. If they need food, there are bag lunches. If they are comforted by Indigenous medicine, they can receive a smudge before their vaccination. If they need a ride to and from the centre, they can call and someone will pick them up.

”You want to make people feel comfortable coming through here, because a lot of people coming through, they’re anxious, they’re unsure about things.” – Dustin Leach

If they don’t have a health card, they can still get vaccinated. If they don’t have a place to stay, Ma Mawi support staff will try to connect them with a shelter. If they don’t have a stable address, staff will mail their vaccine cards to a place such as Siloam Mission or Main Street Project. The centre keeps lists of resources for social supports, such as food hampers.

The goal, in short, is to knock down any and all obstacles for someone who decides they want to get a vaccine. Ma Mawi staff is there to help, and that starts the minute visitors walk through the doors, Leach says. Making them feel safe and welcome is a big part of the job, especially when some are nervous.

“You want to make people feel comfortable coming through here, because a lot of people coming through, they’re anxious, they’re unsure about things,” Leach says. “A lot of people come here with uncertainty. From what we’ve heard, it’s been the complete opposite of that once they leave. People are happy. It’s been pretty cool, man.”

That philosophy has continued outside the centre’s doors. In the summer, staff ran an outreach van, rolling through some of Winnipeg’s core neighbourhoods, ready to offer information and support to folks they met. They got to know some of the homeless people who lived on the streets, and were able to connect many of them with the vaccine.

“We met a few characters, and people that you’ll never forget,” says Adam Wuttunee, one of the centre’s outreach workers, and a smile touches the corners of his eyes.

Wuttunee never imagined himself doing something like this. Raised in Red Pheasant Cree Nation, close to North Battleford, Sask., he’d worked as a short-haul trucker in Saskatoon. In January 2021, he moved to Winnipeg to be with his girlfriend; a few months later, a relative suggested he come work for Ma Mawi’s vaccine centre. He figured he’d give it a shot.

At first, he was intimidated by the idea of talking to people; he’d spent years pulling 12-hour shifts alone in a truck. But before long, he got used to it,and then he witnessed the gratitude of the people he met and how optimistic they were about the vaccine.

Those words changed his perspective, too; he has a lot more respect for health-care workers now, he says.

“I never really realized how big of a deal medicine and the health-care system and all of it was,” he says. “People take it for granted sometimes. I really realized that a lot of people are really thankful for what we do, even though what I do is just a small part, but I’m getting a lot of ‘thank you for being here.’ I’m a lot more thankful now, that’s for sure.”

And when he thinks about all of the traditions at the centre, the morning smudge, the bagged lunch, the multitude of ways they help their community and each other, he feels the heartbeat of the culture he grew up with: bringing everyone in and leaving nobody out. Doing what you can to take care of each other, even if it has to start small.

“We’re majority Native people here, and that’s one of our values, is giving,” Wuttunee says. “I know a lot of Native people out there who would give you the shirt off their back, even if they had nothing in their pockets. That’s kinda like how some of the co-workers that I know here are. Even if they had their last $20, they’d give it to you.

“It’s just about helping, and giving, and not expecting anything back,” he adds. “It’s a good feeling. That’s how it is in our culture, we don’t really have a lot, we don’t really need a lot, but we take pride in helping people and just making sure they have a good day. Because you never know what anybody’s going through, right?”

”It’s just about helping, and giving, and not expecting anything back.” – Adam Wuttunee

Wuttunee checks the time. He has to leave in a minute to pick up a guy who called for a ride to get his vaccine.

So the work carries on, doing whatever it takes to get Manitobans protected, one by one. It matters. Somewhere out there in the province, there is someone who is alive today only because they were able to access the supports that the Ma Mawi clinic offered; there is someone who felt comfortable accessing a vaccine, where they might not have somewhere else.

Now, what Delaronde wants Manitobans to know is that the vaccine centre’s doors are wide open. In the early weeks of the effort, when supplies were tight and demand was high, the urban Indigenous clinics respectfully requested only Indigenous people attend, to conserve resources for a demographic hit harder than most by the virus.

These days, there’s no need for such requests; they have more than enough resources, both vaccine and human, for everyone who chooses to visit. She points to one partition wall near the centre’s entrance, where staff invite visitors to write a word of welcome in their own mother tongue. It includes Cree, Ojibway, Vietnamese, Tagalog and a Sikh greeting.

“Working here, you can feel the community spirit, the warmness — that’s what I feel that Ma Mawi brings in the heart of the North End,” Delaronde says. “You can feel it when you walk in this building…. Everyone is welcome here, and we’ll do our best to provide the best service for anyone, regardless of what they come in with. Just accepting people where they are.”

The Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre’s urban Indigenous vaccination centre is open six days a week at 363 McGregor St. for walk-in or appointment visitors. Its hours of operation are Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., Tuesday and Thursday from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. and Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Appointments can be made by calling 1-844-626-8222. Anyone needing a ride can call 204-599-6841.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.