Doctors working ‘in the dark’ as COVID hospitalizations surge Front-line physicians describe chaos inside ERs with patient-care standards falling, people spending days on stretchers in hallways

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/01/2022 (1428 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Manitoba doctors say they’re in the dark about how the province will deal with an ever-increasing patient load as record-high COVID-19 hospitalizations continue to rise.

Omicron-variant infections are spreading at a lightning-fast rate but haven’t yet peaked in the province and hospitals are already bursting at the seams. Contingency plans to handle the overload haven’t been shared with front-line staff.

“We’re actually looking at unprecedented numbers of people that are requiring hospital admission, so where the beds are going to come from to take care of the sick COVID patients is a big unknown to most of us,” said Dr. Renate Singh, an anesthesiologist who works at Grace Hospital and Health Sciences Centre.

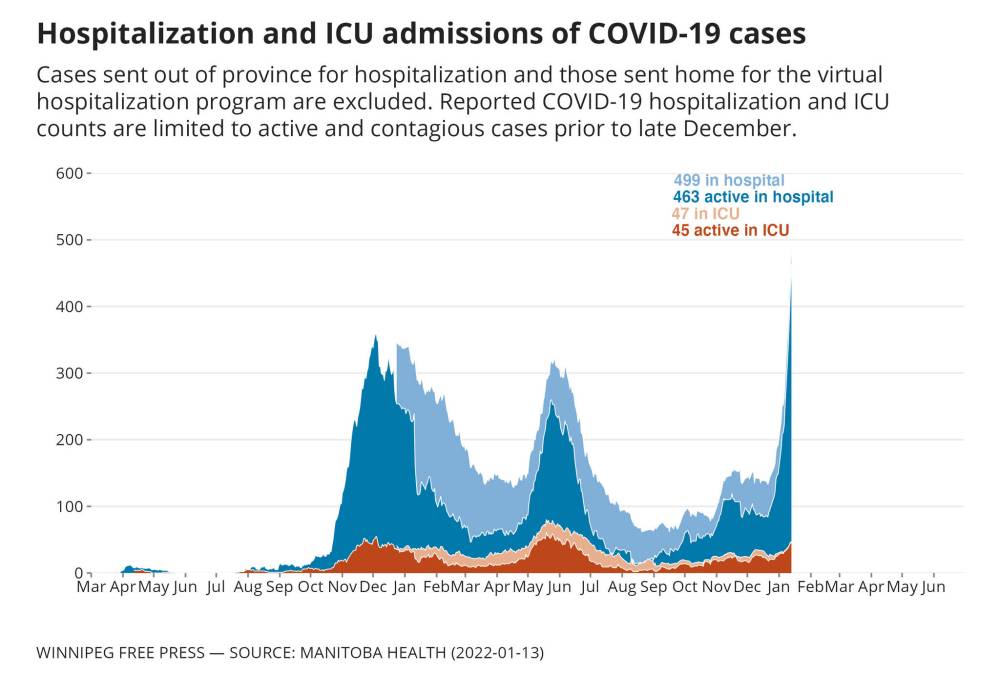

There were 499 patients hospitalized with the virus in Manitoba Thursday, 45 more than a day earlier. In intensive care, there were 102 total patients; the pre-pandemic baseline was 72 ICU beds. And in hospital medicine wards across the province, just 160 of a total 1,460 beds were available, Shared Health said.

Dozens of patients are being transferred daily to rural and community hospitals when beds become available, and ambulance service is already stretched thin.

The situation has doctors and nurses concerned about having to lower already compromised patient-care standards; it’s already common for patients to be in emergency rooms and hallways for days before they can be admitted.

Health officials and the province’s leaders need to acknowledge this is “an impending crisis,” Singh said.

“There’s a real danger that we are overlooking an opportunity to be contemplating how to manage a mass-casualty sort of situation, because that is very potentially where we could be in the next couple of weeks based on the continuing growth of Omicron in our community,” she said.

Several physicians who spoke to the Free Press have called for short-term lockdown measures to slow the flood of hospital admissions, considering the Omicron variant spreads much more quickly and thus is expected to peak more quickly than previous COVID-19 waves that have hit the province.

Doctors Manitoba president Dr. Kristjan Thompson didn’t go that far Thursday, but speaking to reporters before his ER shift at St. Boniface Hospital said the situation is worse than it’s ever been and doctors are “in the dark” about contingency plans they’ve been requesting for two years.

He spoke of seeing a patient “writhing in agony” for 10 hours with a burst appendix last week, and watching another throw up in a bucket while waiting for emergency care. Meanwhile, staff are getting sick and burning out.

“Part of what’s contributing to that moral distress is not knowing what that plan is and what I need to do to prepare when we reach these scenarios where we just don’t have the capacity,” Thompson said.

The virus is not endemic yet, and it’s not time for Manitobans to give up and accept that everyone will inevitably get infected, he said, adding that kind of thinking is just going to further flood the health system.

Thompson said he fears doctors will have to move to providing a “crisis standard” of care, below regular standards, “where we’re providing the best care we can, but it’s not our regular standard of care. It’s because we don’t have the capacity or the resources.”

But he said doctors won’t abandon patients.

“We have to do everything we can to not only prevent death, but to mitigate suffering, because there’s a lot of that happening right now,” he said.” I’m sure when the dust settles, there’ll be assessments and studies and I think it’s something we really do need to look at. Because as a society, we really do need to reflect on what has happened and we need to make sure something like this doesn’t happen again.”

The queue of backlogged surgeries and diagnostic tests in Manitoba has increased by at least 1,204 since last month, according to an estimate from Doctors Manitoba. The total backlog now stands at more than 153,320 cases.

“These aren’t just numbers; this is 10 per cent of our population,” said Thompson.

Even before Omicron began to surge in Manitoba, ERs were overwhelmed.

Jonathan Corobow’s grandfather was among patients who have been forced to wait days for admission on a stretcher in the hallway.

Corobow said the 97-year-old man waited three days with stroke symptoms before he was admitted to Grace in late November.

Unable to get around on his own and struggling to speak, he arrived at the ER by ambulance and waited eight hours before being seen by a doctor.

“It was a grotesque experience, knowing slowly and surely that the stroke symptoms were just setting in and no one was really doing anything about it,” Corobow said. “Despair is the word that I keep coming back to.”

His grandfather died on Dec. 11 at the hospital.

“Something doesn’t seem like he got the full extent of the care that a likely stroke patient should have,” Corobow said.

“The system is clearly not working.”

— With files from Danielle Da Silva

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.