Diagnosis: incarcerated Stony Mountain inmate’s repeated health complaints minimized, ultimately costing him his life

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/12/2021 (1541 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

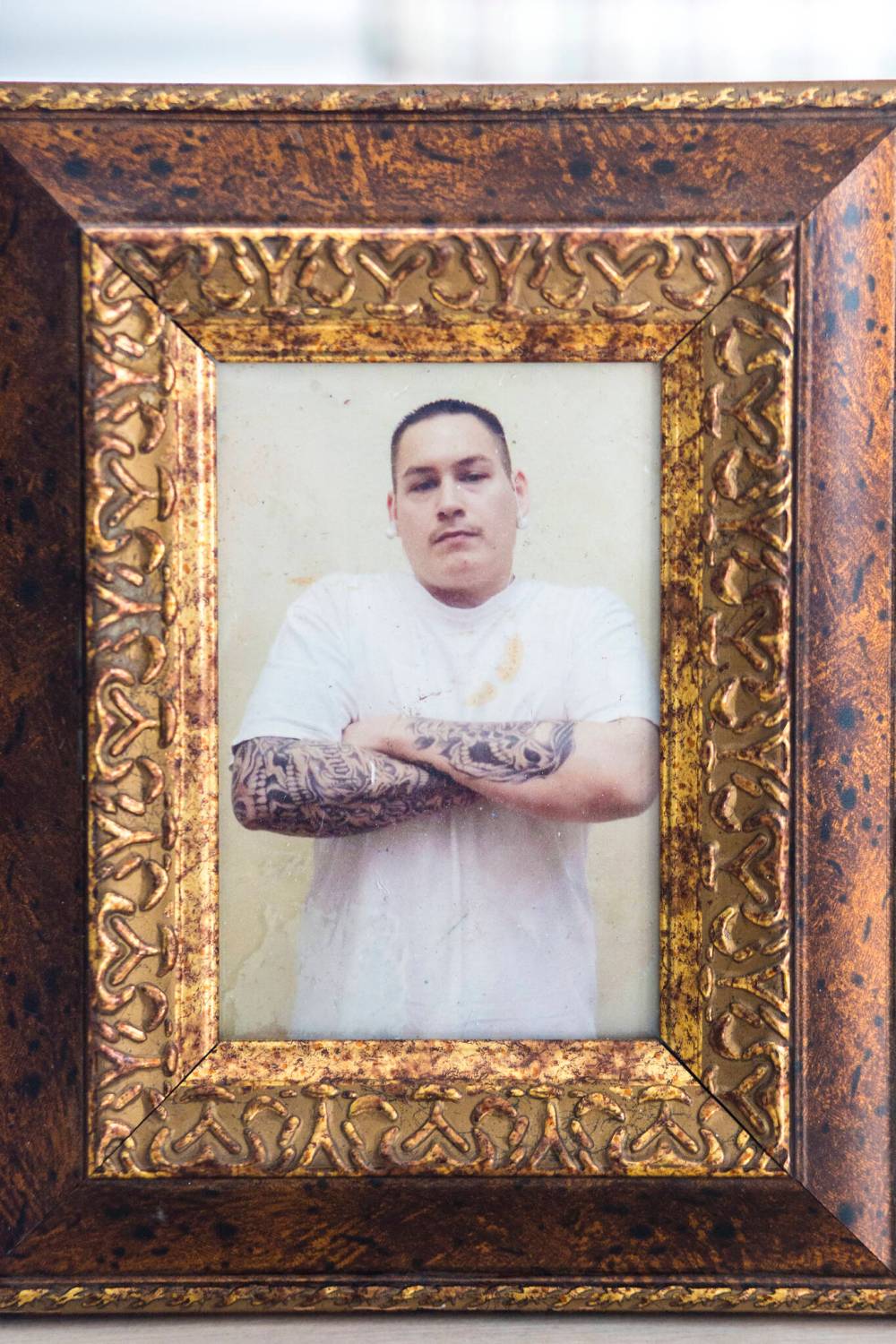

Gertrude Lamoureux sits on the couch in her William Whyte neighbourhood home in the North End as the midday sun pierces through the living-room window. At 82 years old, she is frail and thin, but her mind is sharp. Her bony fingers grip the sides of an ornate picture frame.

It holds a photograph of her grandson, Shawn Poitra; it is the only photo she has of him.

“I had him since birth… I only had two, a son and a daughter, but I raised five grandkids. He was the youngest. That’s my baby. My big baby,” she says.

They called her Grandma Gertie. Her husband worked for the municipal government and she worked with special-needs kids in schools. She takes pride in the fact they worked full-time and raised the children without social assistance.

The love she has for her grandchildren is evident in the warmth of her voice when she tells stories about them, and recounts the twists and turns their lives have taken. At times, her voice breaks with emotion and tears well in her eyes; in other moments, she sounds angry.

Poitra was born May 25, 1990, and before everything that was to come, before the drugs and the run-ins with the law and the phone call in the spring of 2016 that left Lamoureux feeling like she’d been stabbed in the chest, she remembers a young boy who loved sports.

He was particularly good at baseball, and during the summer months he would spend hours in the yard playing catch with his brother. The boys would throw the ball back and forth until the light faded from the sky and Lamoureux thought their arms would fall off.

“He was a very quiet child, but very, very good. He never got in trouble,” she says softly.

“I don’t know why that boy went wrong.”

● ● ●

It started with a fight over a gold chain.

It ended with one man dead, three others in prison and families forever changed.

And while this story is about Shawn Poitra, and what happened to him at Stony Mountain Institution, it is also about much more than him. It is about the medical care, or lack thereof, provided to inmates in federal prisons across Canada. It is about the bodies — whether by suicide, homicide or “apparent natural causes” — that keep piling up.

This is the eighth instalment in the Winnipeg Free Press investigative series Life and Death Behind Bars into prison conditions in Manitoba.

On May 12, 2016, there was a drug deal at the apartment complex at 236 Talbot Ave., where Shawn Poitra and Raymond Ducharme, both 25, lived. The two men grew up together in Point Douglas, where pot led to pills and the drug trade.

The deal went wrong. The drugs exchanged hands but the money didn’t. A fight broke out and Ducharme’s gold chain was stolen.

The thieves fled. Poitra and Ducharme loaded into a car and used social media to track them down. They learned two of the culprits were living at a house at 672 Wellington Ave. On the drive over, they picked up a friend named Pierre Contois, then 21, who owned an AK-47 rifle.

The house is small with a carport and a white fence. A brick chimney juts out from the slanted roof. Windows — one long and rectangular, the other short and square — flank either side of the front door, with a small walk-up of steps.

It was owned by George Prieston, 29, who had nothing to do with the events earlier that day. The plan was to storm the house and hold him hostage until the gold chain was returned. The trio bought a package of hotdogs from a nearby store to distract Prieston’s dog.

Poitra was the first through the door and he physically struggled with Prieston. Both men were big. When it looked like Prieston might get the better of Poitra, bullets started flying. Contois panicked and shot Prieston once in the back. A round also struck the dog.

The men fled in Ducharme’s car. When the police arrived, they found Prieston bleeding to death on the kitchen floor and the dog whimpering in the yard. The hotdogs were scattered on the front steps near a pile of vomit. An officer shot the dog to put it out of its misery.

Poitra and Ducharme were arrested within hours. Contois was picked up months later.

The police called Lamoureux and told her Poitra had been booked for murder. She went to the police station to pick up his personal belongings but was not allowed to see him.

“It was just so stupid. A gold chain. Why do you need a chain like that anyway? Plain stupidity.” – Gertrude Lamoureux

“It was just like somebody stabbing you. Horrible. You just dislike everybody who was with him. But he didn’t have a gun to his head. He should have had more brains,” she says.

“It was just so stupid. A gold chain. Why do you need a chain like that anyway? Plain stupidity.”

Poitra and Ducharme pleaded guilty to manslaughter in March 2018 and were sentenced to 13 years in prison. With time served, they had 10 years remaining on their sentences when they were transferred to Stony Mountain on March 26, 2018.

Contois took his case to trial, hoping to beat the charges. He was convicted of second-degree murder in January 2019. He is incarcerated at Stony Mountain.

● ● ●

When Poitra stepped into Stony Mountain — located 24 kilometres north of Winnipeg up Highway 7 — he was 27 years old. Surprisingly, prison officials placed him in a cell with Ducharme, one of his co-conspirators in the crime that landed him behind bars.

Roughly eight weeks after arriving at Stony, Poitra told Ducharme that he’d found a growth on his testicle. He was a large man, about six-foot-five, who enjoyed weightlifting. He wondered if he’d suffered a hernia while working out. It was around the time of his 28th birthday.

The Free Press spoke with three inmates who were close with Poitra at Stony Mountain, and four family members who were in contact with him during this period. The group included his cellmate, friends, siblings, grandmother and the mother of his children.

Poitra’s family and friends say he made frequent complaints to prison staff about his worsening health condition and increased pain, but did not receive adequate medical care.

It is a story of neglect that fits a broader, nationwide pattern of allegations against the Correctional Service of Canada, all documented in the form of reports, research papers, inmate accounts, academic studies, independent investigations and lawsuits.

“He put in the request to see the doctor,” Ducharme says. “Probably within the month he got it checked out… (the doctor) told him it’s nothing to worry about.

“Then it kept getting bigger and bigger.”

As the pain got worse, Poitra began to worry. He filled out more medical request forms and his condition was monitored. Eventually, he told his close friends the growth had swollen to “the size of a softball.”

It would take roughly a year for Poitra to be taken to a community hospital for testing.

“The doctor said, ‘Maybe a hernia.’ They didn’t take him to the hospital from Stony. He kept complaining. They said, ‘Take it easy playing basketball or whatever you have to do. It’s just a hernia, just a hernia,’ they kept telling him,” Lamoureux says.

“But it wasn’t a hernia. Then he started getting really sick.”

● ● ●

People sentenced to federal prison tend to be in poorer health than the average Canadian. While in prison, they receive access to worse medical care than the general public does. As a result, their mortality rates are high.

From 2004 to 2017, at least 753 inmates died in Canadian federal prisons — an average of 53 per year, or one every week. The average annual number of inmate deaths has stayed remarkably consistent over the past two decades.

At least eight prisoners have died at Stony Mountain so far in 2021; in the past 22 months, 16 inmates have been reported dead. In April 2021, a Free Press investigation revealed that Stony Mountain was the deadliest federal prison in Canada.

While inmates die by a variety of means — drug overdose, suicide, homicide — the leading cause of death is what CSC describes in press releases as “apparent natural causes,” which refers to illness or old age.

According to a report from the federal prison ombudsman, the Office of the Correctional Investigator, cancer is the leading cause of “natural death” among inmates.

“The time in custody provides an opportunity to intervene to improve health,” reads a March 2016 article — The Health Status of Prisoners in Canada — from the Official Publication of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Improving inmate health would lead to “valuable secondary benefits for society,” including “decreasing health-care costs, improving health in the general population, improving public safety and decreasing re-incarceration.”

The authors note that under the United Nations’ Nelson Mandela Rules, which outline minimum standards for the treatment of prisoners, inmates must have access to the same health services available in the country at large — an obligation “not consistently met in Canada.”

When Nelson Mandela was released from an apartheid South African prison in 1990, after being locked up for 27 years, he observed that, “No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.”

According to a lawsuit filed earlier this year by the John Howard Society — a prisoner advocacy group founded in 1867 — the delivery of health care in Canadian federal prisons amounts to unconstitutional conduct and a mass breach of charter rights.

Canada’s socialized medicine system effectively ends at the locked doors of federal penitentiaries.

Under the Canada Health Act, in the legislation that devolves the administration of health care from the federal to the provincial governments, inmates are explicitly excluded as “insured persons.” Aside from a few exceptions, in most provinces inmate health care is the responsibility of CSC.

The lawsuit alleges the health care received by federal prisoners is “systematically below” what is available in the community, leading to “reductions of prisoner lifespan” and “cruel treatment.”

CSC declined an interview request for this article. Instead, it sent a written statement, responding to various questions submitted by the Free Press. The federal prison agency denied that inmates receive substandard medical care.

“As the legal claim made by… the John Howard Society of Canada is currently before the Court, it would be inappropriate to comment on specifics related to this case,” a CSC spokesman wrote.

“Our health services are accredited by Accreditation Canada, which is the same organization that accredits hospitals and other service providers… The care provided by our health-care staff is no different than the care provided to members of our communities.”

JHS executive director Catherine Latimer says society no longer sees the infliction of pain as an acceptable form of punishment for social transgression. And yet, she notes, poor and underfunded health care in prisons inevitably leads to pain, illness and death.

“I think there is a mistaken belief that somehow access to health care should be diminished if you’re serving a sentence… but the truth of the matter is there is nothing in a sentence that should lead to substandard health care,” Latimer says.

“You’re denied your liberties, but you’re not supposed to be denied access to health care. I’m not sure why these issues have not been brought to the forefront or acted upon in the past, but certainly our lawsuit is an attempt to ensure those issues are corrected now.”

● ● ●

By the summer of 2019, Poitra was certain something was seriously wrong with his body. About a year after his first appointment with the prison doctor, he was sent to a community hospital for testing. The results were not good: testicular cancer.

He was taken to St. Boniface Hospital in late-July for surgery to remove the cancerous testicle. While at the hospital, Poitra took to social media, hoping to reconnect with old friends on the outside. He posted that he was recovering from surgery but didn’t elaborate.

Soon he was back at Stony Mountain, but not long after, he began complaining of pain again.

“All of a sudden, the back of his neck started hurting. He put in a couple requests to the doctor, telling him, ‘This feels weird. Something is there’… I remember he had a little bump there (on the back of his neck,” Ducharme says.

“He’d have a Freezie there all the time, freezing it.”

Poitra was given antibiotics for a suspected infection. His condition didn’t improve, so eventually he was sent back to the hospital for further testing. The results were even worse: the cancer had spread throughout his body.

Ducharme says Poitra began chemotherapy in the fall of 2019. Prison guards would escort him from his cell to a transport van that would drive him to the Health Sciences Centre in Winnipeg for treatment. Then he’d be driven back again to experience chemo sickness in his cell.

“He couldn’t eat anything. He was up all day and all night just throwing up. That was after he started doing chemo. He was stuck in his cell…. We were trying to get him to eat but he couldn’t hold it down. He was just puking it up,” Ducharme says.

Around December 2019 the guards took Poitra to HSC for the last time. Ducharme never saw him again.

No one from CSC contacted Lamoureux, his designated next-of-kin. She learned Poitra was in the hospital only when she got a call from an inmate in Headingley Correctional Centre, who’d heard, through the prison grapevine, that he was dying.

She set out to HSC with her sister in search of her grandson.

“We were wandering around. We looked everywhere. It’s big and it’s very confusing. We walked from floor to floor until somebody told us he was in the basement. He was in bad shape. We walked in there and he screamed, ‘Grandma, you’ve finally found me,” Lamoureux says.

“And he kept saying, ‘Grandma, my head is sore. My head is sore.’”

“And he kept saying, ‘Grandma, my head is sore. My head is sore.’” – Gertrude Lamoureux

She visited him every day for a week-and-a-half. Poitra’s six-foot-five frame had shriveled, reduced to “skin and bones.” His three children came to say goodbye as two prison guards looked on from an observation room.

“By that point, I think he was just anxious to go. Lots of pain. Lots of pain,” she says.

“He was praying with us.”

Shawn Poitra died Jan. 5, 2020. He was 29 years old.

The next day, CSC issued a four-paragraph press release reporting his death of “apparent natural causes,” and noting his next-of-kin had been contacted. Lamoureux never received a phone call or medical paperwork from CSC.

His body was cremated. That summer, Lamoureux drove to San Clara, just north of Roblin, where her family is from, and buried Poitra’s ashes in a cemetery plot next to her mother, father and brother. At the funeral service, Poitra’s aunt read from the Bible.

“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth forever…. To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: a time to be born and a time to die… All go unto one place; all are of the dust and all turn to dust again.”

● ● ●

Lamoureux remains angry that no one from Stony Mountain or CSC contacted her about Poitra’s admission to the hospital or provided paperwork related to his death. She believes the prison did not take basic steps to keep her grandson alive.

“It’s cruel. Very cruel,” she says.

Latimer says she knows of other stories like Poitra’s.

“We’ve heard from a number of families where loved ones contracted cancer and complained for a long time. But by the time it was diagnosed it was already third and fourth stage, so the chances of having adequate and life-sustaining treatment were terribly diminished,” Latimer says.

“I’d say about a half-dozen cancer cases have been brought to my attention.”

Testicular cancer is most common in men aged 20 to 39. It is highly treatable, with a five-year survival rate of 95 per cent. According to the British Journal of General Practice: “Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of testicular tumours have a negative impact on patient survival.”

In a report into compassionate release in Canadian federal prisons, the OCI noted that it is easier for inmates to get medical assistance in dying than it is to be released to die with dignity in the community when suffering from a terminal illness.

Correctional Investigator Ivan Zinger has repeatedly said: “The state should never be in the business of shortening people’s lives inside a prison — it’s just wrong.”

In one case highlighted by the OCI, “an elderly patient” dying of cancer requested release to a community-based hospice — a move that was supported by prison staff who did not view him as high risk to reoffend.

“The response from the Parole Board was that it wanted to see the offender managed in a minimum-security institution before granting him release to the hospice. He was eventually released to the community, but died two hours after release,” the OCI wrote.

In April 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, an inmate named Derrick Snow petitioned CSC for compassionate release. Snow had a lengthy criminal record of property offences, but no history of violence.

He’d first been sentenced to federal prison at 16 where he was sexually abused by an older inmate. At the time he petitioned for early release, Snow had less than four months to serve on a theft sentence. He had cancer, pulmonary disease and diabetes.

His legal team asked for a quick decision from CSC but no response came. Then his lawyers filed a motion in federal court seeking to force Snow’s release. It was only after the courts got involved that CSC agreed to release him to live with his sister in London, Ont.

Snow was released on April 21, 2020 and died four months later, on Aug. 24.

At Stony Mountain, the family and friends of Poitra are not the first people to make allegations of medical malpractice and a pattern of misdiagnosis.

In July, former Stony Mountain inmate Colton Parkes filed a lawsuit against the prison and its physician, Dr. Jerry Bergen, alleging that a misdiagnosis of a physical injury sustained during a weightlifting accident left him partially paralyzed with a catastrophic back injury.

Despite complaining about pain and worsening conditions, Parkes’ lawsuit claims he was not provided “meaningful medical care.” His attorney, Jeffrey Hartman, a prison lawyer from Toronto, says the case is similar to many he’s handled at penitentiaries across the country.

“There’s a culture of neglect where medical rights are not taken seriously…. Because prisoners become ‘othered,’ and deemed less deserving of human dignity than the rest of us, the medical care comports with that,” Hartman says.

“CSC is great at having a policy for everything and having everything look nice and shiny and perfect on paper, but then you get into these places and it’s a very different story. There are some employees that are true professionals… and then there are some really bad seeds.”

Bergen is the same physician who treated Poitra.

On a crowdsourced website reviewed by the Free Press, where patients can post their experiences with medical professionals, Bergen has received 38 reviews dating back to 2006; of the 38 reviews, 10 make allegations of misdiagnosis, including two that reference cancer cases.

A review of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba website shows that Bergen has not been sanctioned or disciplined by the regulatory body during his career.

The Free Press requested comment from Bergen — submitted through his lawyer Nicole Watson — about the Poitra and Parkes cases.

“The Personal Health Information Act prohibits a physician from disclosing any personal health information about a patient without their consent,” Watson wrote.

“This prohibition applies even when a patient issues a claim or chooses to speak to others about their personal health information. So Dr. Bergen cannot provide any information to you with respect to his care of Mr. Parkes or any other patient, otherwise he would be in breach of PHIA.”

As the populations in prisons continues to get older, the issues raised by critics of CSC health-care policies are only going to become more acute. As of Aug. 1, 2021, more than 1,300 federal prisoners were age 60 and older; 140 were older than 75.

Meanwhile, there are nearly 3,000 inmates in the 45 to 59 age bracket, currently.

Every Stony Mountain inmate who spoke to the Free Press raised serious concerns about health care at the prison. One nurse who works in the health unit said she believes many inmates use illicit substances for pain management because they can’t get access to proper prescriptions.

“They swept my brother under the rug. For a year they gave him no medical attention. He should have been out for testing right away…. It’s not fair. He was a father, a brother, a grandson. He was part of our family,” says Scott Poitra, Shawn’s older brother.

“And no one answers for it. No one has to answer for it.”

● ● ●

When a prisoner dies in federal custody, CSC conducts a “mortality review.” Families have long complained they are left in the dark when their loved ones die behind bars, and at times have had to file access-to-information requests and pay processing fees for basic documentation.

When documentation is released, it is often heavily redacted.

The federal prison authority declined make a spokesperson available for an interview with the Free Press. It also declined to comment on Poitra’s case, saying privacy legislation “provides very strict parameters on the disclosure of personal information, including medical information.”

“CSC takes the death of every person in our custody very seriously. We conduct a full quality-of-care review that includes identifying opportunities for improvements,” a CSC spokesman said in a written statement.

“When someone dies in our custody, we contact any next-of-kin and help answer their questions. They can request a copy of the report of the quality-of-care review. It is important to allow this process to take its course.”

But Lamoureux — whom the Free Press has confirmed was listed as Poitra’s next-of-kin — maintains she was never contacted by CSC.

In February 2014, the OCI published a report into CSC’s mortality-review process, calling it “flawed and inadequate,” and noting that reviews often take more than two years to complete.

“Moreover, the mortality-review process has yet to generate a single finding, recommendation, lesson learned, or corrective measure of any national significance…. Even what quality of standard of care issues are noted, they appear to be not acted upon,” the report reads.

To test whether CSC internal investigations were doing a good job of holding its own staff accountable, the OCI hired an independent “senior medical practitioner” to review 15 cases where inmates had died of “apparent natural causes” in federal prison.

“The expert review raises significant quality of care issues: questionable diagnostic practices; incomplete medical documentation; quality and content of information sharing… and delays and/or lack of appropriate followup on treatment recommendations,” the OCI wrote.

“Despite these critical findings, all (15) individual mortality reviews conducted by CSC assess the care provided to the deceased inmates as ‘congruent’ with ‘applicable’ health care standards and policy.”

Lamoureux and the rest of Poitra’s family, as well as his fellow inmates, believe that if he’d had access to better health care at Stony Mountain, his cancer would have been caught sooner and he’d still be alive today.

● ● ●

Shawn Poitra is not an overly sympathetic character. In a dispute over a gold chain, a man was shot and left for dead. For his role in that crime, he was sentenced to prison.

Yet as terrible as the crime was, he did not deserve to die. That he did was the result of a deeply dysfunctional correctional system that displays institutional indifference to death.

It is a system that fails to keep inmates alive.

So Poitra is one more name to add to the growing list of people who die behind bars, the inmates for whom a prison sentence turns into a death sentence.

“There is all this research, there is all this noise being raised about this, but the government doesn’t care. What the government cares about is money,” says Hartman, the Toronto lawyer.

“And until it costs too much to maintain the status quo, I don’t think it’s going to change.”

Shawn Poitra may not deserve our sympathy.

But his treatment deserves our outrage.

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

.jpg?h=215)