‘An almost impossible task’ Ripple effect of ideology, policy, pandemic drove ICU overload: Winnipeg physician, former MP Eyolfson

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/10/2021 (1511 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

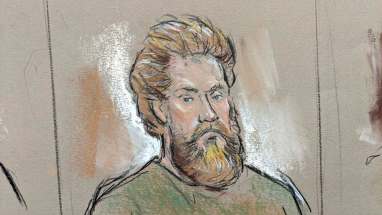

The lowest point in the pandemic for Dr. Doug Eyolfson was when he lost count of the ICU patients he had treated during the third wave who had succumbed to COVID-19.

“The number of people I had cared for, before they were intubated, had conversations with them, knew things about them — and then watched them slowly die, I lost count of the number,” said Eyolfson, who spent this spring working in the Grace Hospital ICU.

“The number of end-of-life conversations that we had with families — I saw more of that in six months than I had in probably a decade in emergency medicine.”

What made it harder for the former Liberal MP is knowing policy choices factored into the number of deaths.

“There’s a ripple effect, throughout the whole health-care system,” he said in a wide-ranging interview.

The Free Press approached Eyolfson to hear what it’s like to be on the COVID-19 front lines, with recent experience as a politician in government.

Eyolfson was an emergency department doctor primarily based out of Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg until fall 2015, when he was elected as Liberal MP for the riding of Charleswood—St. James—Assiniboia—Headingley.

Four years later, he lost to Conservative candidate Marty Morantz, returning to a hospital system that, by 2019, seemed to be in chaos.

By all accounts, Manitoba’s health-care expenditures were unsustainable in the long term when the Pallister government took office in 2016. Eyolfson’s own Liberal team had kept in place a federal health transfer that doesn’t meet provinces’ growing expenses.

Yet, the provincial PC government’s health reforms have been widely viewed as chaotic. Three Winnipeg emergency rooms were replaced with urgent care centres, but paramedics and patients couldn’t always tell which one to visit.

“It happened so suddenly, and not with a lot of forethought,” Eyolfson said.

The government insists it’s making hard choices that will provide Manitobans with better care in the long run. However, Doctors Manitoba said last week the system was run so tightly before the pandemic, it buckled under marginal increases in patients.

“They were given an almost impossible task,” said Eyolfson. “(With) COVID happening shortly after these reforms took place, it made for a perfect storm of a just critically overloaded system.”

While the first wave largely spared Manitoba, the second hit a year ago, pulling staff such as Eyolfson from emergency wards to intensive care units.

There was little reprieve for exhausted health-care workers this spring. In May, 200 doctors signed a letter urging Manitoba to further restrict non-essential gatherings, as the third wave hit other provinces hard.

The province insisted it had the right balance, but by June, it had the fastest COVID-19 spread than any other jurisdiction in North America.

“That was the low point, just seeing all this severe illness and death happening at the same time,” he said. “Family members saying goodbye, over (video calls); I’ll never forget that. I never thought I’d see that in my lifetime.”

By late May, personnel from the Canadian military, STARS or other medical-transfer companies would enter hospitals to prepare ICU patients for transportation, in the end wheeling a total of 57 of them out and onto planes headed for Ontario, Saskatchewan or Alberta.

“There should have been more requests for (federal) help earlier.” – Former Liberal MP and ICU doctor Doug Eyolfson

Within a few hours, another patient would take their place.

“There should have been more requests for (federal) help earlier,” he said. “The provinces had to ask for it.”

Eyolfson has a chipper manner, which at times was awkward on Parliament Hill. His partisan jabs in the House never quite landed when delivered with an upbeat tone.

But underneath his happy demeanour, Eyolfson holds a deep anger — over Manitobans he says died because of local political decisions.

“They’ve been making a lot of ideological decisions, and holding off on making a lot of the necessary restrictions,” he said. “They’ve been afraid of their base, that would claim that their so-called rights are being violated by lockdowns and vaccine mandates.”

The PC government insists it follows the advice of public health, but that guidance is never shared with anyone other than ministers, who are the ones making all COVID-19 decisions.

After the resignation of premier Brian Pallister in late August, the province has taken a more cautious approach, which seems to have spared Manitoba the dramatic rise in cases seen in the rest of Western Canada.

Now, the main issue is unvaccinated Manitobans, who make up the vast majority of those hospitalized due to COVID-19.

Eyolfson said he and his medical colleagues will never deny care to anyone who’s sick. However, he says, they have to actively ignore the fact it’s unvaccinated people maxing out ICUs.

As a result, patients who should be coming in from the adjacent emergency ward end up transferred to other hospitals. Doctors and nurses are getting pulled off operating room shifts to deal with unvaccinated ICU patients, thus delaying surgeries.

“It is frustrating to see these effects in the health-care system,” he said.

“We can’t be held hostage by people who want to make bad decisions.” – Eyolfson on vaccine holdout health workers

Eyolfson fully supports measures to require health-care workers to get vaccinated, saying there is virtually no pushback from his colleagues in Winnipeg. He’s glad Manitoba didn’t push back its vaccination mandate, as Quebec did this month.

“That just will empower those who resist it,” he said. “We can’t be held hostage by people who want to make bad decisions.”

As the pandemic grinds on, “I think it’s premature to say there’s any end in sight to this,” Eyolfson said. “I don’t think life is going to return to the way it was for quite some time.”

He has hope, however. Manitoba has largely warded off a fourth wave, which Eyolfson attributes to a vaccine requirement for non-essential businesses and requiring mask use indoors.

“That was the high point, because that says the government is actually making decisions based on data,” he said. “I hope they continue to do so.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca