Disquieting trend The Winnipeg Police Service’s public information office is larger than ever, but it’s providing less information, raising safety concerns and questions about transparency, a Free Press analysis reveals

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/09/2021 (1627 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was a hot and sticky summer, one of the warmest on record in decades, with a drought that brought ruin to farmers in the countryside and apocalyptic, smoky skies that made Winnipeg feel downright dystopian.

The sun burned a pale red; the sky was pallid and jaundiced, as if gauze had been draped over the horizon. Haze descended upon the Prairies from the hundreds of wildfires raging out west.

With the smoke came temporary refuge from the pandemic, a brief interlude between the third and fourth waves; at times, it almost felt as if life were returning to normal. People, sick and tired of being cooped up at home, ventured back out into the world.

Patios and newly minted outdoor bars filled up, bringing relief to cash-strapped business owners. Live music could be heard reverberating through the air. Daily case counts and deaths dropped to lows not seen since the start of the first plague year.

Walkers and joggers took to the river trails, which snake through the heart of the city alongside the muddy waterways that give Winnipeg its name. Some ran, while others sought a relaxing stroll with family and friends.

But among those who took to the trails this summer was no ordinary citizen in search of exercise and sunshine. There was also a serial sexual predator at work, armed with a knife, stalking the pathways evening and night, looking for women and girls to attack.

And attack he did.

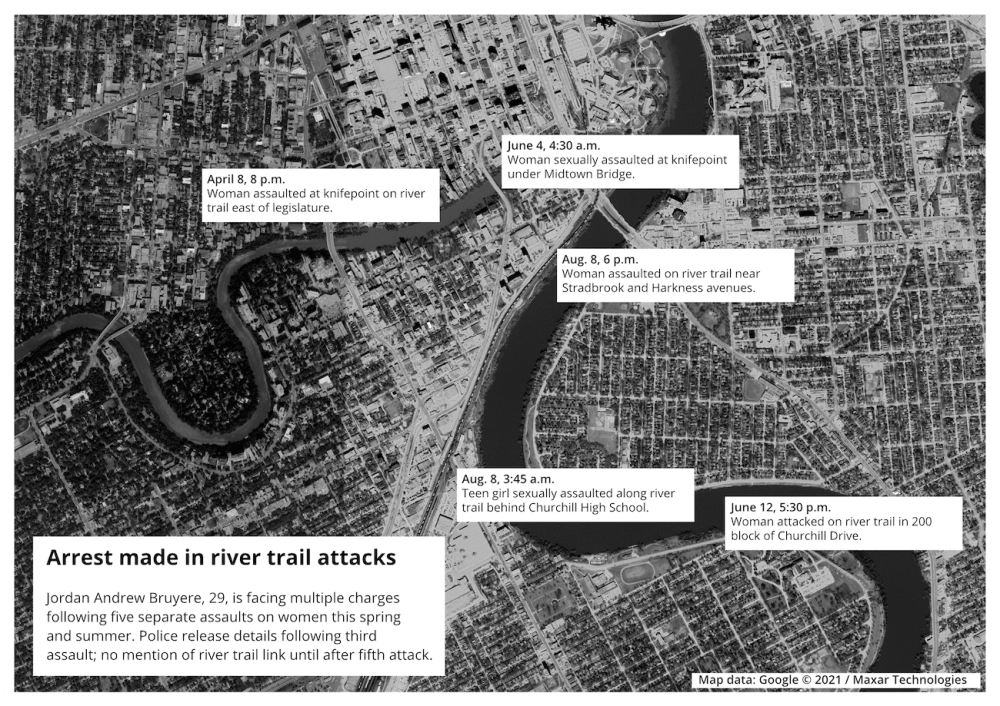

There was a pattern: a man approached a woman alone along the river trail, always late in the week (Thursday through Sunday) during the evening or early morning hours before light pierced the sky.

The first attack came on April 8, sometime around 8 p.m., when a woman in her 30s was walking east of the Legislative Building, where lush trees rise from the embankment, providing a canopy above the bending gravel path. Suddenly, she was grabbed from behind by a man.

The man had a knife. The woman screamed and struggled with her attacker, managing to squirm away and run to safety. She reported the assault to police, suffering only a minor injury.

The Winnipeg Police Service did not notify the public of the attack. There was no news conference, nor was a press release issued.

The predator struck again less than two months later, at about 4:30 a.m. on June 4, when a woman in her 20s was walking along the 300 block of Assiniboine Avenue, which runs parallel to the river trail. She passed a man and asked if she could borrow his cellphone.

The man said yes, but told her to follow him along Donald Street towards the Midtown Bridge where they could get better reception. He then turned on her, grabbing her from behind and dragging her under the bridge at knifepoint.

He sexually assaulted her and ran away. The woman reported the attack to police and was treated for injuries.

Again, the WPS did not notify the public of the attack. There was no news conference, nor was a media release issued.

Eight days later, at about 5:30 p.m. on June 12, a woman in her 20s was walking along the river trail near the 200 block of Churchill Drive. Like the others, she was attacked from behind and pulled to the ground.

The woman struggled and screamed. Eventually, the attacker let go, and she ran to safety and contacted police.

This time, the WPS issued a news release: four paragraphs, 129-words.

“The suspect is described as male, 35-40 years old, 5-11, average build. Black hair buzz cut style, wearing a grey t-shirt, black cargo pants, a black mask, and black sunglasses,” it read, pointing readers to “personal safety tips” available on the WPS website.

There was no mention of the two previous attacks along the river trail.

At about 3:45 a.m. on Aug. 8, a 15-year-old girl walking along the trail behind Churchill High School was grabbed by a man and raped; she reported the attack to police when it was over.

Hours later, at about 6 p.m., a woman in her 20s was jogging along the trail near Stradbrook and Harkness avenues when a man grabbed her from behind, pulled her to the ground and attacked her.

It was only the following day, on Aug. 9 — four months, or 123 days after the first attack — that police told the public there had been a string of assaults against women along the river trail. The WPS issued a written public advisory. There was no news conference.

“Detectives are investigating several incidents between April and August 2021, involving females being physically accosted at various points along the Red River trail system. The victims were grabbed from behind, pulled to the ground, and threatened with a weapon,” the advisory reads.

“The incidents varied from the early evening hours when it was still light out into the early morning hours when it was dark outside. All the incidents occurred along the west Red River trail from the Osborne Bridge south along Churchill Drive, to the Elm Park footbridge at Jubilee Avenue.”

Weeks later, on Aug. 24, police released surveillance footage of a suspect. And then on Aug. 27, police held their first news conference in the case, announcing that following tips from the public, an arrest warrant had been issued for 29-year-old Jordan Andrew Bruyere.

Bruyere was arrested and charged with three sexual offences related to the attack on the 15-year-old girl behind Churchill High School. After being released on bail, he was re-arrested on Sept. 9 and charged in the other cases.“If we knew it was a stranger-on-stranger attack, a sexual attack with a weapon– if we knew that, we would release on that. Guaranteed that would pass all of the critera.” — Const. Rob Carver

“Investigators did some fantastic police work and were able to make arrests in all five incidents,” said Const. Dani McKinnon, a newly minted member of the WPS public information office, during a news conference following Bruyere’s second arrest.

“(They) cast a very wide net and eventually their investigation became more pinpointed and we learned (a single suspect) was responsible.”

While the charges against Bruyere have not been proven in court, there is little doubt the investigation was complex and challenging for sex crime detectives, who connected the string of attacks to a single suspect.

But questions remain: why did police not notify the public of the first two attacks that appeared similar and took place in an area that has seen multiple high-profile sex crimes in recent years? And if they had, would things have been different for the other victims?

● ● ●

“Man dies after medical incident during police interaction.”

That was the headline on the news release issued by the Minneapolis Police Department in the hours after a then-unknown George Floyd, 46, died on May 25, 2020 — 16 months ago today.

The nearly 200-word statement, written by the head of the MPD public information office, made no mention of the fact officers restrained Floyd on the ground, that a knee was placed on his neck and how long the confrontation with police lasted.

“(The suspect) physically resisted officers. Officers were able to get the suspect into handcuffs and noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress. Officers called an ambulance. He was transported to (hospital) by ambulance where he died a short time later,” the statement read.

All of the details included in the now-infamous press release were, technically speaking, true. But they were also profoundly deceiving, employing all the hallmarks of passive language and vague euphemism that often characterize police communications.

When a police officer shoots and kills someone, it is called an “officer-involved shooting.”

And when Derek Chauvin murdered Floyd by placing a knee on his neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds as the dying man repeatedly gasped, “I can’t breathe,” it was labelled a suspect death from a medical incident following a police interaction.

The public knows what truly happened that day only because of a cellphone video recorded by a 17-year-old bystander. The video went viral, shocking people around the world and leading to the prosecution of Chauvin and other officers on the call.

When it comes to police press releases, it’s clear that — from the standpoint of law enforcement — the more euphemistic and passive the language the better. It is what the English journalist George Orwell called “political language.”

Phraseology such as “officer-involved shooting” is needed, Orwell noted, “if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.”

For police departments across North America, there is Before George Floyd and After George Floyd. Nothing has been the same since, or ever will be again. His murder ushered in a new era of policing, where calls for defunding and even abolition have gone mainstream.

Winnipeg has been no exception.

But aside from the initial scrutiny of the George Floyd press release, less attention has been paid to the operations of public information offices — the media liaison units employed by police departments — compared to issues of funding, oversight and accountability.

And given that PIOs often determine what the public does and does not hear, and colours its perception of incidents through carefully chosen language, more scrutiny is needed, say multiple academics who spoke to the Free Press.

In Winnipeg, prior to 1985, the police did not have a formalized media policy, and information was released to news outlets on a sporadic, ad-hoc basis. There was no official spokesperson for the department, aside from the police chief, who rarely spoke to reporters.

The main contact for the media was the Winnipeg Police Service duty inspectors office, which was staffed by a single individual 24 hours a day. Journalists could also walk into the Public Safety Building or go to crime scenes to get information and quotes from officers.

In 1985, the WPS created a formalized media relations position. Daily news conferences were held so reporters could be updated on overnight crime and information was released to the public as directed by the police chief.

By 1989, the WPS decided the role would be better handled by a civilian, and Eric Turner was hired. He held the post until 1995, when the force reverted back to staffing the position with an officer.

The WPS public information office is currently a six-person unit, staffed with three officers — constables Rob Carver, Jay Murray and Dani McKinnon — an office assistant, a communications co-ordinator and public affairs manager Kelly Dehn, a former CTV reporter and editor.

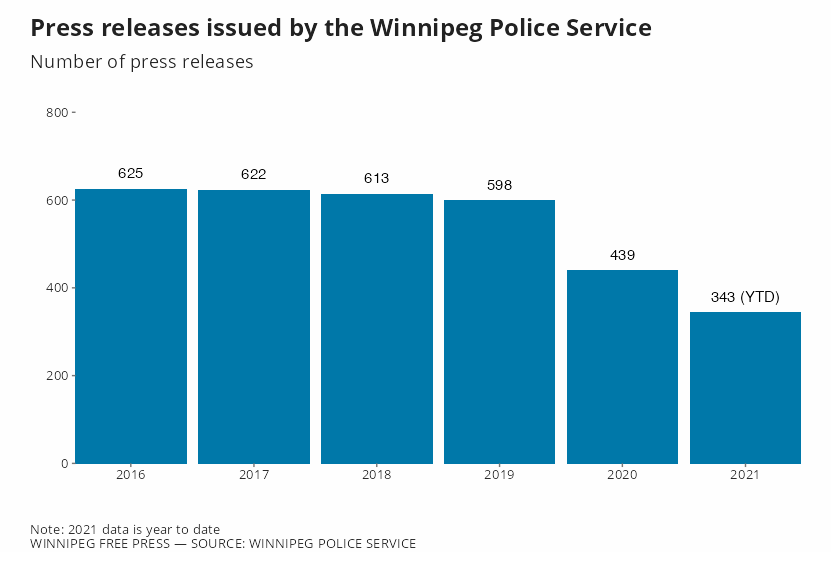

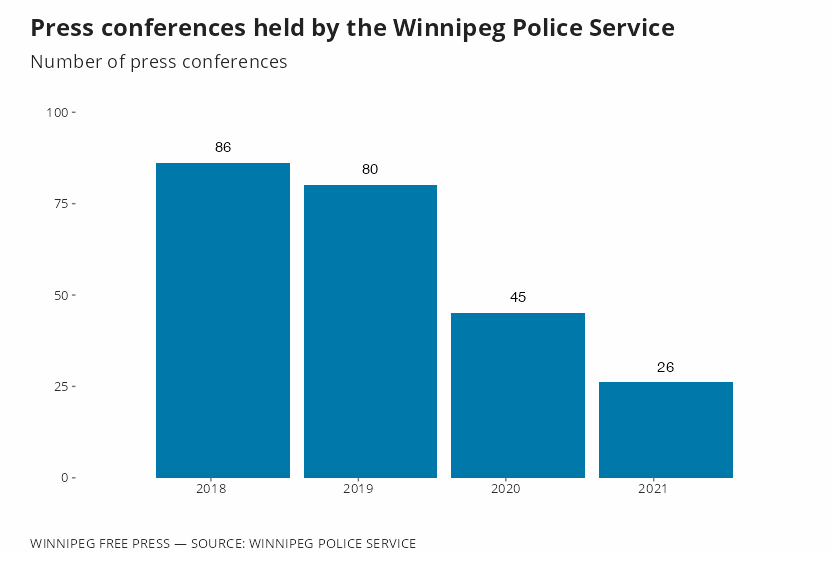

Despite the expansion of the PIO unit, a Free Press analysis of WPS communications, in the form of releases and news conferences, shows the level of proactive engagement from the department in recent years has been on the decline.

And those long-term trends of disappearing news conferences and diminishing press releases came to a head during the summer with the river trail sex attacks.

● ● ●

Crime rates in Winnipeg have risen steadily after sinking to historic lows nearly a decade ago; public police communications have declined at the same time.

From Jan. 1, 2018 to Aug. 31, 2021, there was a 69 per cent decrease in the number of Winnipeg police news conferences. The most precipitous drop came in 2020, when media events were nearly halved, falling by 43.8 per cent from the previous year.

In 2018 and 2019, the WPS averaged a news conference once every 4.3 days; by early 2020 (prior to Floyd’s murder) that figure had fallen to once every seven days. After Floyd’s death, it fell further, averaging a news conference every 10 days.

The service is on track to reach a new low in news conferences this year, with just 26 so far in 2021 — an average of one every 10.5 days. The WPS is currently averaging about 36 annual news conferences, or roughly three a month.

By comparison, the Vancouver Police Department — the only police service in Canada the Free Press could find comparable data for — has held 42 news conferences in 2021, or an average of six per month, which is roughly double the WPS rate.

Meanwhile, the number of press releases issued by the WPS has also been on the decline. The police service wipes its public communications from its website on a rolling 36-month basis, but provided the Free Press with data going back to 2016.

From 2016 to 2018, the number of press releases from the department remained relatively flat, but has dropped every year since. In 2016, the WPS issued 625, compared to 439 in 2020 — a decrease of roughly 30 per cent.

A review of communications from other Prairie police departments shows that from 2018 to present, Winnipeg (1,993) issued fewer press releases than Saskatoon (3,264) and Regina (2,171), despite having a larger population and higher crime rates.

Meanwhile, a review of communications from the Toronto Police Service from Aug. 10 to Sept. 10 found it issued 276 press releases — ranging from homicides to sexual assaults to missing persons — which is close to what the WPS has issued thus far in 2021 (343).

Since the third quarter of 2018, there have been 17 “officer-involved shootings” reported by the WPS. Only one of those police shootings appeared as a single-subject release, and in seven cases it was listed below other crime items of the day.

In addition to reviewing WPS public communications, the Free Press also spent two weeks at the Law Courts in Winnipeg on a daily basis, charting new overnight criminal charges in the city among people seeking bail to get out of the remand centre.

That resulted in identifying dozens of cases, including serious offences ranging from robberies and shootings to drug trafficking and weapons charges, that were not announced by police.

When the Free Press presented its findings to the WPS, the department agreed to an in-person interview with all three of its public information officers, as well as Dehn, the public affairs manager. The interview was on the record, wide-ranging and lasted about an hour.

Const. Rob Carver, the longest-serving member of the PIO, said the numbers from other police departments in Canada — in terms of press releases and news conferences — are irrelevant here; he said the WPS has its own criteria on what information to release to the public.

“We wouldn’t look at (other police departments’) numbers and decide we’re doing too many or too less,” Carver said.

The members of the PIO said news conferences and press releases do not capture the full scope of their communications with the public, pointing to social media, public-safety announcements, radio and TV hits and statistical reports as other examples of their work.

The WPS also recently released a slickly produced video, featuring Chief Danny Smyth and community activist Sel Burrows walking around the Point Douglas neighbourhood discussing an investigation that took down a drug house in the area, another pivot in their efforts at public engagement.

“We’ve really tried to build this office in a way that it’s easier to communicate with the public,” said Const. Jay Murray, pointing out the WPS has been a leader among Canada’s police in livestreaming news conferences on Facebook.

And members of the unit feel local media have devoted fewer resources to crime reporting in recent years, resulting in much less interest and engagement from reporters when they do issue releases or hold news conferences.

The members of the PIO explained their process for determining whether a crime will be reported at all and, if so, whether it’s in a release or a news conference.

Factors include the expected level of media inquiries or public interest, issues of community safety, whether the incident is gang-related or part of an ongoing criminal investigation and the nature and complexity of the crime.

Often, particularly in cases involving organized crime or the use of confidential informants, investigators are hesitant — if not opposed — to the PIO releasing information.

“We’re seeing that a lot more. We’re now running into an issue where investigators are saying, ‘We don’t want anything out on this… I’ve been around a long time. We’re seeing more than ever that investigators don’t want something out,” Carver said.

The unit has also undergone staffing changes that impacted operations, and the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it technical challenges that may help explain some of the recent downward trends in communications.

Const. Tammy Skrabek, a longtime member of the PIO, retired in early 2020. Her replacement, Const. Rachel Vertone, decided the position wasn’t a good fit after six months on the job. Const. Dani McKinnon, who joined the office last November, said there is a “steep learning curve.”

“I don’t think scrutiny of police spending has ever been as high as (it is now). It’s not that easy to just add positions to units within the service… There is a lot of different things, I think, that have contributed to maybe — I hope — it’s a temporary downturn in communications,” Murray said.

The members of the unit stressed that nothing in its metric has changed as to what information is released and how it’s communicated.

“If anything, there’s a bigger push… I see it as we’re trying to be more engaging,” Carver said.

There were different explanations provided for the failure to release details on the first two river trail assaults.

It is noteworthy that it was not the first time a woman had been attacked in that area in recent years, which has served as a hot spot for high-profile sex crimes in Winnipeg.

In November 2014, it was the site of the brutal beating and sexual assault of a teen girl, whose bruised and battered body was dumped in the near-freezing Assiniboine River. The case gained widespread national attention.

And in August 2018, an 18-year-old woman was walking along the river trail near Bonnycastle Park when she was assaulted and raped by two men in a brazen daylight attack.

In both cases, the WPS promptly issued notifications to the public.

But in the April 8 attack, the incident was presented to investigators as an assault with a weapon and, perhaps, an attempted robbery, according to members of the public information team. At the time, it did not seem sexual in nature, and did not rise to a level of severity where they felt a press release was warranted.

“Police communications is really about communications policing. It’s about framing, including some information and not including other information. Police communication specialists are very good at framing. They’re selective of the information they include and keep out.” — Kevin Walby, criminologist at the University of Winnipeg

In the second attack, on June 4 — when a woman was sexually assaulted at knifepoint along the trail — two possible explanations for the lack of public notice were advanced.

“If you look at June 4 on its own — and again, not to be disrespectful at all — it didn’t present much differently than a number of sexual offences that the unit deals with. It wasn’t unique and it didn’t appear to be in the pattern,” McKinnon said.

When pressed further, Carver said he was involved in discussions around whether to release details on the June 4 attack, which looped in investigators from the sex crime unit.

“There were certainly variables about (June 4) that investigators… were looking at saying, ‘Does this fit any others?’ And I’m going to add, ‘Did it even happen the way it was presented?’ Part of an investigator’s job… is to confirm that, in fact, it is an accurate representation,” Carver said.

“We need to check everything — was there drugs or alcohol involved? Is her recollection accurate? Is she shielding someone? Did she know the guy? All of those things add complexities.… There are often question marks and sometimes they take longer (to get answered).”

Carver said that unanswered questions led to the decision not to notify the public, in part due to concerns related to the force’s inability to “pull something back” once it’s released.

“If we knew it was a stranger-on-stranger attack, a sexual attack with a weapon — if we knew that, we would release on that. Guaranteed that would pass all of the criteria,” he said.

“Unless an investigator says, ‘We’ve got stuff to figure out here, and we cannot pull it back, so you’re going to have to wait.”

Eight days after the June 4 attack, the suspect struck again.

● ● ●

The Free Press spoke to three criminologists and a gender-based violence expert, asking for thoughts on how Winnipeg police communicated with the public on the river trail sex attacks and, more broadly, the changing role of public information offices.

All four were critical of the lack of public information after the first two attacks.

“The way these things get communicated is very important. In Toronto, there has been more than one case, famous cases, about communicating sexual assaults and why it’s important to be super-transparent,” said Andrea Gunraj, vice-president of public engagement for the Canadian Women’s Foundation.

Marian Valverde, a criminologist and activist who has served in a civilian capacity on police-community liaison boards, was more cutting in her response.

“Why am I not surprised?” Valverde said.

Both women pointed to the Jane Doe case — also known as the Balcony Rapist case — in Toronto in the mid-1980s.

Beginning in 1985, a serial rapist named Paul Callow stalked the city’s Church and Wellesley neighbourhood, repeatedly victimizing women who lived alone in second- and third-floor apartments with balconies that could be reached by climbing.

Police chose not to publicize the crimes, concerned the unidentified perpetrator would be tipped off and evade capture if they issued a warning.

On Aug. 14, 1986, long after police realized they had a serial rapist on their hands, Callow struck again, raping a woman — later known as Jane Doe — in her second-floor apartment on Wellesley Street East. Callow was later arrested and sentenced to a 20-year prison term.

Jane Doe was his fifth confirmed victim. When she learned police had chosen not to warn the public about the previous rapes, she sued the department for failing to protect her and violating her right to safety.

Justice Jean MacFarland of the Ontario Superior Court ruled in her favour, arguing Toronto police “failed utterly in their duty to protect” Callow’s victims, denying them the “opportunity to take steps to protect themselves.”

Jane Doe was awarded $220,000 in damages.

“The way these things get communicated is very important. In Toronto, there has been more than one case, famous cases, about communicating sexual assaults and why it’s important to be super-transparent.” — Andrea Gunraj, vice-president of public engagement for the Canadian Women’s Foundation

It wasn’t the last time a lawsuit of that nature was filed in Canada. In 2016, a Newfoundland woman sued the province after being victimized by Sofyan Boalag, a convicted rapist who targeted six women in downtown St. John’s in 2012.

Boalag’s sexual assault spree lasted from September to December 2012. The plaintiff in the lawsuit was the last of his victims. Police only notified the public of the crimes on Dec. 7, three days before Boalag was arrested.

“The defendant failed to take reasonable steps, or any steps, to perform its duties of care to the plaintiff, including the duty to warn the plaintiff as a member of an identifiable group at risk,” the lawsuit alleged.

Gunraj said the necessity of timely, transparent police communications when it comes to public acts of sexual violence were first established in the Jane Doe case, and events in the decades since have only underscored their importance.

“The Jane Doe case is a classic, historical case about why it’s really important for the police to be reporting these things from the start and be very transparent about it so people can be fully aware and take appropriate precautions,” she said.

“I think we learned that lesson back in the 1980s.”

On the broader trends in Winnipeg with declining police communications, University of Toronto criminologist Jamie Duncan said it’s “important to know what public institutions are doing with their resources.”

“It’s really important not to forget there are interests at stake in what (police departments) choose to release. It’s often about conveying a perception that police protect us from a violent and disordered world,” Duncan said.

“I’m always interested in more transparency, especially when it’s transparency that’s being eroded, as opposed to never having existed in the first place.”

Another example of eroding transparency, he said, is the move by police across Canada to encrypt radio communications long used by media outlets to monitor crime crime and law enforcement operations. The WPS encrypted its scanners in 2010.

“More transparency, especially with an institution like policing, is always better. The move to encrypt scanners is a move to reduce accountability,” Duncan said.

Kevin Walby, a criminologist at the University of Winnipeg and a leading scholar on police transparency in Canada, said he believes law enforcement agencies across the country take a “risk-management approach to communications,” and the WPS is no exception.

“A lot of times there is no depth to the communication. They don’t release many details, even if it ends up creating more obfuscations.… They carefully manage the information flow, and what they’re really doing is managing the risk to the police,” Walby said.

“Police communications is really about communications policing. It’s about framing, including some information and not including other information. Police communication specialists are very good at framing. They’re selective of the information they include and keep out.”

For Duncan, the issue boils down to a single question he believes journalists, academics and concerned citizens alike must grapple with:

“Are police communications in Winnipeg serving the interests of the police or the public?”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.caTwitter: @rk_thorpe

michael.pereira@freepress.mb.caTwitter: @__m_pereira