Promise after the plague The past 12 devastating months have revealed unpleasant truths about the world we live in; it's not possible to turn back the clock, but a return to 'normal,' will offer opportunities to honour the dead by improving the lives of the living

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/03/2021 (1824 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was before the loss began.

Before patient zero turned up in Manitoba, before the first of us died, before the virus ripped through our community, before the homes of our elderly were stricken with sickness, before the hospitals were overrun, before the doctors and nurses revolted, before the economy shut down, before the daily death toll became nightly news.

Before all that, there was a hockey game.

A Monday in Winnipeg. The temperature drops below zero but the sun is out in full force. A normal weekday afternoon fades into a normal weekday evening. As rush-hour traffic streams through downtown, 15,325 people file into Bell MTS Place for a 6 p.m. puck drop.

No one stands two metres apart. People greet one another with handshakes and hugs, not nods and elbow bumps. There are no hand-sanitizer pumps stationed throughout the arena. “Social distancing” is not in the public lexicon. There are no masked faces in the crowd.

It is March 9, 2020 and the Winnipeg Jets are playing the Arizona Coyotes. The visitors draw first blood, surging ahead with a 2-0 lead in the first period. And right about then, Daniel Headford — seated in the lower bowl, celebrating his 30th birthday — feels dread.

“It was a pretty boisterous crowd. The Jets were right in the thick of it to get one of those last playoff spots. I think people were starting to feel optimistic because the team seemed like they were starting to jell,” Headford says, thinking back on that night.

“Then the Jets go down 2-0 and you get that sense of dread.”

But in the second period, the Jets respond with two goals, tying the game. And with 8:27 left in the third, Cody Eakin picks up the puck in the Coyotes’ zone on a busted play, cuts across the net and backhands the go-ahead score past goaltender Darcy Kuemper.

As the final seconds of the game tick away, Mark Scheifele adds an empty-netter, and the Jets beat the Coyotes 4-2. With their third consecutive victory, the Jets slide into a wild-card spot in the National Hockey League playoff race.

The crowd cheers and screams and spills into the streets, with some trickling into nearby restaurants and pubs. Drinks pour down the throats of thirsty customers and highlights from the game flash across TV screens. People laugh and talk, eat and drink, and go home.

“At the time, COVID wasn’t at the forefront of my mind, or many others, I think. We probably thought it was a bit overblown. There were troll comments on social media about how it was just the flu. I remember hearing about how the NHL was keeping an eye on it,” Headford recalls.

And that’s when things start moving quickly.

In 48 hours, the World Health Organization classifies the novel coronavirus a global pandemic. In 72 hours, Winnipeg records its first presumptive case of the virus, and the NHL suspends its season. In a week, Premier Brian Pallister declares a state of emergency in Manitoba.

The plague year begins.

The virus is not contained; the centre struggles to hold.

Things fall apart.

●●●

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” writes Joan Didion in The White Album, an essay on the tumultuous, kaleidoscopic years of the late 1960s.

“We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live… by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

How does one impose a “narrative line” on a year like 2020?

Widespread social and economic disruption. International travel ground to a halt. Borders closed. Countries shut down. Citizens, by and large, at home. Agricultural protests and panic-fuelled supply shortages. Children barred from schools and elders locked alone. Businesses going under and families struggling to stay afloat. Governments balancing public health and civil liberties. A summer of racial reckoning and a new year of political unrest.

The ninth-deadliest pandemic in human history.

More than 2.5 million dead. About 22,000 Canadians. In excess of 900 Manitobans.

The loss is staggering. The scope of it all — the suffering and vanished human potential — is unspeakable. It is a loss of biblical proportions, a tidal wave of calamities, something akin to a rapture: millions of souls snatched away in the blink of an eye.

In Manitoba, the loss began on March 27. Public-health officials identified her as a woman in her 60s from Winnipeg. Her name was Margaret Sader, and she worked as a customer-service representative at a dental-supply company. She contracted the virus, was taken to hospital and transferred to the ICU, where she died.

“She was caring. She was a wonderful, wonderful human being who would help anybody with anything. She was just one of those people that you wanted to be around,” says a longtime colleague.

An Internet search of Margaret’s name turns up countless examples of her posting kind, thoughtful messages to the online comment sections of obituaries for friends and acquaintances after their deaths.

The life she may have lived was taken. The lives of those she left behind have been irrevocably changed, like the lives of so many others during the pandemic. And there is nothing to do with that suffering — as C.S. Lewis once put it — but to suffer it.

There were other losses, too. Some small, but still important in their own ways, others big. How does one convey the myriad losses that have been sustained? Not the lives lost, but the businesses, jobs and savings? The loss of education, recreation and routine? The loss of nights out with friends and holiday celebrations with family? The loss of community, connection and control?

So much loss, so many ways.

Given all that collective grief, is it any wonder people have tried to cling to whatever fleeting sense of normalcy they can grab hold of? Experiences that once felt mundane now feel luxurious: the way a trim at the barber shop feels like a trip to the spa; or breakfast at a greasy spoon tastes like fine dining; or drinks with friends at a park seems like a night out on the town.

For Mark Hildahl — one of the 15,325 fans at that last Jets game — a sense of normalcy lives in the ticket stub from that night one year ago. Every once in a while, he pulls it out just to look at it. And if you ask him why, he’s not entirely sure how to answer, or even if he completely understands.

“It’s kind of like a souvenir. I’m always a little bit sentimental. It’s been hard to bring myself to get rid of it. It’s kind of a nice memory…. It brings a bit of comfort to look at the ticket,” Hildahl says.

It’s like a relic from another world, or an artifact from a perished civilization.

It’s like a portal back to life before the loss began.

●●●

The man sits at the table and takes a sip of water.

He is wearing a white dress shirt with a purple tie and a black vest. The cuffs of his sleeves are rolled onto his forearms. There is a silver watch on his left wrist. He is clean shaven and looks calm and rested. As he speaks, he occasionally taps the fingers of his right hand on the table.

“The World Health Organization and the Public Health Agency of Canada, along with Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, are actively monitoring the situation in Wuhan, China with the novel coronavirus,” the man says.

“While the risk to Manitobans is low, health-care providers are being asked to be aware of clients with relevant travel histories and symptoms that could raise the possibility of infection.”

It is Jan. 23, 2020 — 49 days before the virus turns up in Manitoba in a woman who had travelled to the Philippines — and this is our introduction to Dr. Brent Roussin. He has held the title of chief provincial public health officer for seven months.

Nothing can prepare him for what happens next. In the coming months, he gives a dizzying number of media conferences — day after day, week after week, as case counts spike and deaths pile up and the pandemic spirals out of control.

Sometimes he is alone – a one-man band relaying the latest COVID facts and figures to Manitobans. Other times, he sits next to the premier, or the health minister, or other public health officials — such as Lanette Siragusa, chief nursing officer for Shared Health — who soon become household names in the province.

The first press conferences come in January and February and early March, before the arrival of the virus. At one of them, on Feb. 7, Roussin does what so many other health officials did in the early days: he tells Manitobans there is no need to wear masks.

“At this time, public-health officials are not recommending the use of masks for the general public. These do not provide any benefit,” Roussin says.

The first case comes March 12 and the first death on March 27. By early April, the advice on masks is reversed, and soon enough, Roussin arrives at every briefing wearing one. It becomes a part of the routine: he sits at the table, removes the mask, takes a sip of water and reads out the latest numbers.

In April, Roussin warns there are early signs of community transmission in Winnipeg, and by the middle of the month, there are 250 cases in Manitoba. The first lockdown begins, and life in the provincial capital takes an eerie, surreal turn.

Shelves in grocery stores are picked clean of coveted items. Empty city buses roll up and down deserted downtown streets. Office buildings and shopping malls, stadiums and arenas all sit vacant. Restaurants and bars are shut down, and stores and public facilities are locked up. People hide in their homes.

But by May 31, there are only 10 active cases in Manitoba, and fewer than 10 deaths.

The summer passes like a dream. As the weather heats up, folks venture outside again, meeting with friends and family in parks, talking and drinking, catching up and checking in. At times, it almost feels like there is no pandemic at all.

In mid-July, Pallister appears before the TV cameras and says it’s time to reopen the economy. Manitobans have listened and learned, he says, and now it’s time for business.

What happens next is old news: the rapid rise to code red.

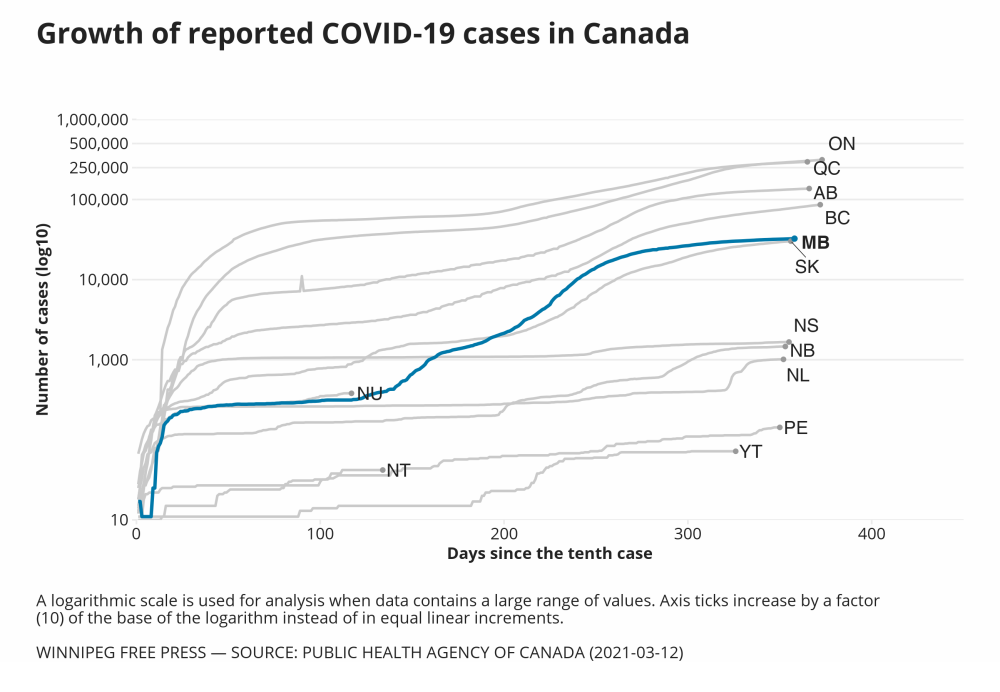

By the end of October, Manitoba has the worst case count per capita in Canada, and Winnipeg is on the verge of another lockdown. Outbreaks are declared in personal-care homes and hospitals are pushed to the brink. Doctors and nurses publicly revolt against the province for not doing enough to stop the spread of the virus. Record numbers of positive cases are reported on a near-daily basis.

Despite months to prepare, the province is caught flat-footed. Wait times at testing sites are long and some people are turned away. There is not enough staff for effective contact tracing, at times forcing infected Manitobans to do it themselves. When pressed for information, officials often display a lack of transparency, and requests for basic public-health information are refused.

On Oct. 30, Roussin holds another press conference. He looks dejected and exhausted in a grey suit. He shifts forward in his chair and an audible sigh escapes his mouth. He puts away his mask, opens a folder on the table before him, takes a deep breath and begins to speak.

“We are reporting three additional deaths. A male in his 80s from Winnipeg. A female in her 80s from Winnipeg. And a female in her 90s from Winnipeg. These cases are all linked to the Parkview Place outbreak. I want to extend my condolences to those families and loved ones,” Roussin says.

“There are 480 new cases that we are announcing as of 9:30 a.m. today.”

The news is grim; there is no end in sight.

The losses keep piling up.

●●●

We have seen this movie before.

Reading through the archives of the Free Press from the years of the Spanish flu pandemic – which infected one-third of the world’s population and killed more than 20 million people — some estimates put the number as high as 50 million — there is an overwhelming sensation of déjà vu.

In the fall of 1918, the Spanish flu — a particularly deadly strain of influenza — stalked the streets of Winnipeg and preyed upon its citizens. The virus was opportunistic, easily spread and lethal. It took aim at anyone in its crosshairs: young and old, rich and poor, men and women.

When it was all said and done — sometime in mid- to late 1919 — it had killed 1,216 Winnipeggers, at a time when the city’s population was just 183,595.

In the beginning, Manitobans heard reports of the deadly virus ravaging other countries, but it did not seem like it would impact them here, in the heart of the Canadian Prairies. Some local health authorities went so far as to proclaim early victory over the disease.

It’s impossible to say for certain how the virus arrived in Winnipeg, but once it did, it spread like wildfire. People started dying and no one was sure how long the situation would last. The expectation seemed to be that it would be over in a matter of weeks.

The city’s health-care services were quickly overrun. Winnipeg not only ran out of hospital space, but also nurses to staff it. Patients were turned away as health authorities scrambled to find locations for temporary clinics.

Countless women stepped forward to volunteer as nurses, often taking the most dangerous job: venturing into homes where the virus had infected entire families to provide care as they died. Some nurses and doctors contracted the virus and died, too.

The city shut down, schools were closed, church was cancelled, movie theatres locked their doors, dance halls and bathhouses were shuttered and there was a ban on public gatherings. Some religious leaders balked and threatened to hold services in defiance of public-health orders.

Entrepreneurs warned they would go out of business and some of them did. Health authorities gave daily updates on the fight against the virus, and claims the pandemic was on the wane had to be walked back in the face of rising case totals.

Compliance with health orders was hit-and-miss. For example, people were supposed to placard the windows of their homes when they got sick, so others would know not to enter. But news reports indicate the preventative measure was carried out only half-heartedly.

The disease took longer to reach First Nations communities, but once it did, the results were even deadlier.

In recent years, scientists have warned the world was overdue for another pandemic. And yet, as the French writer Albert Camus wrote in 1947: “There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.”

●●●

On the last day he ever spoke, Manuel Calisto asked if he was in prison.

It was Nov. 1, the morning of his 88th birthday, and his daughter Eddie Calisto-Tavares, was shaving his face, because the dementia had done such damage to his brain and COVID had done such violence to his body, that he could no longer groom himself.

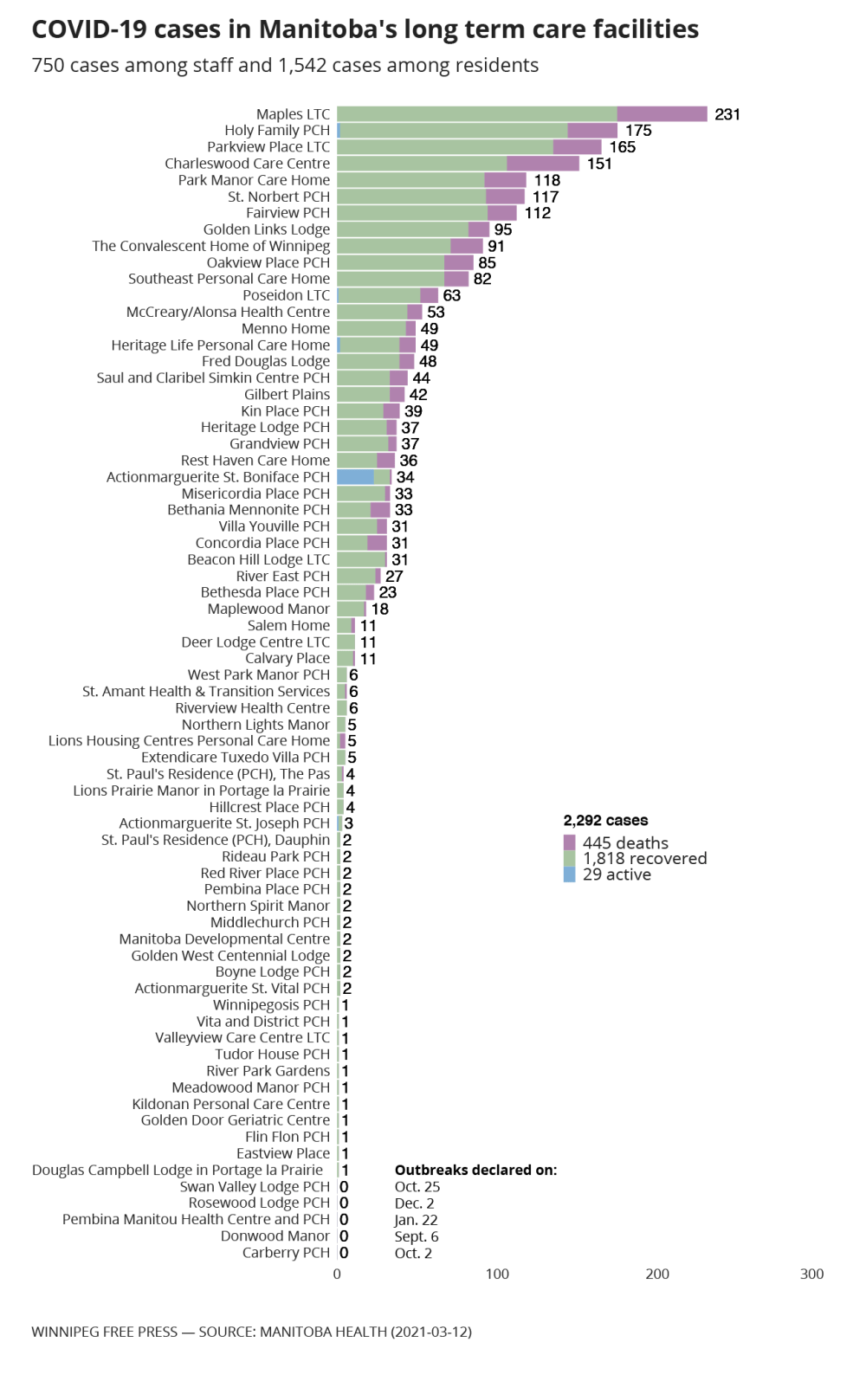

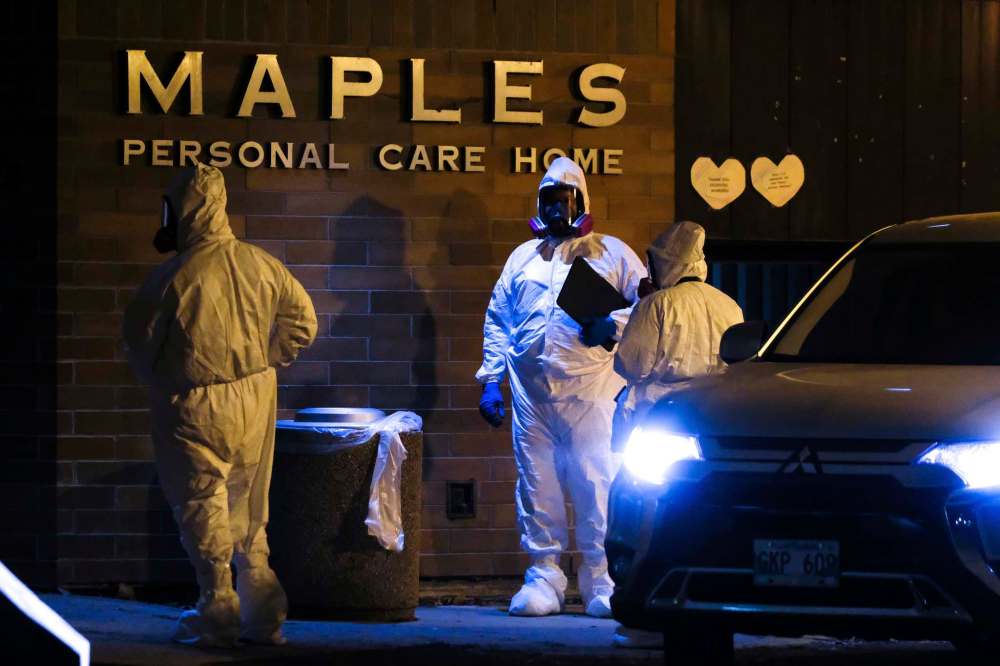

Ten days later, he was dead — one of 56 souls claimed by the horror last fall at Winnipeg’s Maples Long Term Care Home.

A week or so before Manuel’s birthday, Eddie got a video call on her cellphone from a staff member at Maples, who said her father had wandered into the hallway and would not return to his room. Given his recent COVID-19 diagnosis, he was supposed to be isolating.

Eddie spoke with her father on the phone and realized he could not follow simple verbal commands — even in his native tongue of Portuguese. She could also tell that her father, who grew up under the dictatorship of Antonio Salazar, was scared and confused.

“He didn’t know where he was and there were all these security guards speaking English to him and he had lost the majority of his ability to speak English,” Eddie says.

“My dad grew up in the regiment of Salazar and anytime you saw cops it was never a good day. In his mind, these security guards were cops.… All of these people are telling him to go back to his room but he doesn’t know what they’re saying, and he’s scared and he’s panicking.”

Eddie had serious concerns about the lack of staff at Maples as the facility battled the outbreak, which was declared on Oct. 20,. She was also worried about the quality of care her father would receive, given his cognitive decline and the language barrier between him and staff.

And so, despite the strict visitation rules in place, Eddie got approval from Revera — the for-profit company that runs Maples and many other personal-care homes in Canada — to become a designated caregiver for Manuel, so she could continue to visit and try to keep him comfortable.

“I fought my way in there,” she says.

In order to do that, Eddie temporarily moved into a hotel. She left her husband and son — a “miracle baby” born with only one lung — behind at home, so she wouldn’t put them at increased risk of catching the virus as she cared for her ailing father.

“My commitment was that I would live in a hotel and take care of my father for as long as it took. I know my dad felt loved and he had the best care, probably, of anyone there, because I was there. He had companionship,” Eddie says.

“I would hold his hand and talk to him and tell him his mom was waiting for him.”

Manuel was a resilient, industrious man who led a remarkable life. Born in Portugal in 1932, he grew up under the dictatorship that ruled the country from the year of his birth to the mid-1970s. As an adult, he fathered 10 children, started a bread-baking business and invested in real estate.

When his parents were about to be evicted from the family home, he purchased the property so they could continue to live there. He was known for his generosity and the famous New Year’s Eve parties he would throw, with everyone from his village invited for food and wine.

In 1972, Manuel moved his family to Canada, settling in Winnipeg, where he used what was left of his life savings to purchase a home in the West End. He became a commercial cleaner for a time, before moving into construction.

He was a robust man with a wide, toothy grin, who loved his family and prized his independence. It was only in 2019, when he was diagnosed with advanced dementia, that he moved into the Maples care home.

Shortly after the outbreak was declared at Maples, Manuel tested positive for the virus. His deterioration was swift.

“My dad was so weak. He became so frail. He shrank. My dad used to be six-foot-two. His face became so tiny. He had no strength anywhere. He had to use a diaper. None of that was there before COVID,” Eddie says.

And it was on that final birthday, right around the time his daughter shaved his face, that Manuel looked to her and asked, if after all he had been through in life, if after all those struggles, he had ended up in jail.

“He said to me, ‘Am I in prison? Is this prison?’ And I said, ‘Oh no, Dad, no, this isn’t prison. This is your new home and I come visit you here. You’re safe,’” Eddie says.

“That was the last day he talked, the last day he used his words.”

Manuel Calisto died on Nov. 11. Over the course of 12 days that month, 25 residents would die in the outbreak. There was such a lack of staff at the facility, and so many bodies piling up, that Maples was unable to file timely death notifications to the province.

The situation came to light only after six ambulances were called to the facility on Nov. 6. The next day, an anonymous paramedic posted to social media to expose what they’d seen on the call: a disturbing lack of staff; hungry, dehydrated residents; dead bodies with rigor mortis set in.

If you ask Eddie what haunts her most from that time at Maples, it is not the memory of her father’s last birthday. It is another memory, from before Manuel died, when he was asleep in his room and, suddenly, she heard cries coming through the walls.

When Eddie stepped into the hallway to see what the noise was about, she did not see any staff members. Aside from herself and the residents, that section of the facility appeared empty.

“There were three people that just kept calling out for help. One was trying to get out and she was just, ‘Help me. Help me.’ And then there was one, ‘I’m thirsty. I’m cold.’ And then there was another one that just kept saying over and over again, ‘I’m on fire. I’m on fire,” Eddie recalls.

“All I could do was go back and forth in the hallway and I would say their name, and I would say, ‘Help is coming. Don’t try to get up. You’ll fall.’ And finally, I just grabbed some water and I went to the lady… and I gave her the water, because there was nobody to hear the cries.”

Eddie falls silent for a moment.

“I still have nightmares about that,” she says.

“I can still hear people calling.”

●●●

The American novelist Thomas Wolfe once penned an essay in which he argued that “loneliness, far from being a rare and curious phenomenon… is the central and inevitable fact of human existence.”

And while it’s unclear what prompted Wolfe’s pessimistic musings in the undated essay, it’s possible his words have never resonated more than today, as the crushing weight of life under the pandemic bears down on people, often evoking feelings of loneliness and isolation.

Much like the virus, loneliness is invisible. You cannot tell, just by looking at them, if someone has been infected. It can also spread in much the same way: as social contagion, passing unseen from person to person, contaminating more and more with the terrible sensation they have been cut off from human connection.

Loneliness is a vast wilderness, a feeling of utter abandonment, a total separation from the companionship and love we all so desperately crave. And when such feelings persist over long periods of time, it is not just one’s mental health that is impacted.

Social isolation alters our brain functioning, dampens our ability to reason and remember, affects our hormones and impacts our bodies’ ability to fight disease. In severe cases, it can lead to anti-social behaviour in children and hasten the onset of Alzheimer’s in seniors.

“What does it feel like to be lonely?” asks Olivia Laing, in her 2016 book The Lonely City.

“It feels shameful and alarming, and over time these feelings radiate outwards, making the lonely person increasingly isolated, increasingly estranged. It hurts, in the way that feelings do, and it also has physical consequences that take place invisibly, inside the closed compartments of the body.”

As the authors of a recent research paper put it: “In short, loneliness kills people.”

“We are social creatures. Social interplay and co-operation have fuelled the rapid ascent of human culture and civilization. However, social species struggle when forced to live in isolation,” Danilo Bzdok and Robin Dunbar wrote in The Neurobiology of Social Distance, published in September.

“These concerns are likely to be exacerbated if there are prolonged periods of social isolation imposed by national policy responses to extraordinary crises such as COVID-19.”

If you ask Sandy Fotty, crisis management director at Klinic — a non-profit, community health agency in Winnipeg — what its counsellors have been hearing from Manitobans in distress during the pandemic, loneliness is near the top of the list.

“We’re all in the same storm but people have different boats…. There were people calling about loneliness and isolation before the pandemic, and COVID has just added another layer of challenges for them,” Fotty says.

“There are also new people calling who are experiencing this in a different way, and maybe for the first time, they are feeling disconnected from their support networks.”

Call volumes to Klinic’s crisis line have been consistently high over the past year, although the agency cannot say whether there has been an increase in callers. That’s because their old phone system was unable to track how many people called in but were unable to connect with a counsellor.

What current numbers show is that for every five people who call the crisis line in need of mental-health support, only one gets through.

“I think that points to a need for more resources,” Fotty says.

On top of feelings of isolation and loneliness, Klinic sees many individuals report concerns about family members, as well as strife within households where people have been forced to live in close quarters since the pandemic began.

At first, counsellors heard from people experiencing intense anxiety and feelings of being overwhelmed by everything happening in the world; now, as the pandemic stretches into its second year, there is an increased sense of desperation and fatigue.

But that’s not to say the situation is devoid of silver linings. Fotty says the pandemic has given some people the necessary time to reflect upon their lives and make changes. It has also laid bare the lack of community mental-health resources, she says, which could lead to better support in the future.

That’s similar to a point made by Arlen Dumas, Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, who was instrumental in establishing the First Nations Pandemic Response Team last March.

Statistics show that Indigenous peoples — alongside other racialized populations — have disproportionately borne the brunt of the virus. That does not come as a surprise to Dumas, who previously served as executive director of the health authority for his home community.

“I’m very attuned to the potential obstacles and roadblocks that exist, in terms of how medical and health services are provided to everybody in Manitoba.… We’re well aware of the vulnerability of our communities. We’re well aware of the gaps in service,” Dumas says.

“There are still community members who remember the Spanish flu. We have people who lived through (tuberculosis) outbreaks. I was health director through H1N1 and I saw how these things impacted our communities first-hand.”

While Dumas says he’s happy with the collaborative work that’s been done between First Nations leadership and the provincial and federal governments, he adds that those successes would not have been possible “had we not kicked doors down.”

First Nations expertise and acumen, Dumas says, have been vital in the fight against COVID-19 in Manitoba. He says it took provincial and federal politicians realizing they needed help from First Nations leadership before their voices were heard.

“Once we do defeat COVID, we’re not going back to the status quo. We’re all going to have to collectively sit back and think, ‘How did we get through this?’ Well, we needed active and meaningful participation from First Nations leadership,” Dumas says.

“The problem is we’re reliant upon systems that are obsolete and archaic and we need to figure out how to modernize them. Unfortunately, there is a lot of systemic racism. There is a lot of systemic discrimination that exists in some of these processes. We need to figure out how to move forward.”

And aside from the fight against the virus itself, the question of how to move forward is perhaps most important of all. As the Indian author Arundhati Roy wrote in the Financial Times in April: “Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.”

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next,” Roy wrote.

“We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world.”

●●●

During the shelling of Madrid in the winter of 1937, at the height of the Spanish Civil War, there was not only a first-aid service to treat people who’d been hit by falling bombs or struck by passing bullets, but also a first-aid service for wounded buildings.

The men who made up that second, more peculiar service were trained as engineers and architects, bricklayers and electricians. Some of them did little more than dig dead bodies from the rubble of collapsed houses.

More than 500,000 people died in the Spanish Civil War, including Canadians who volunteered for the fight. The conflict marked the first battle against fascism in Europe, predating the Second World War by three years. Despite the sizable death count, the men who provided care to bombed-out buildings were even busier than their medical counterparts.

And that’s because — as noted by journalist Martha Gellhorn — when they weren’t “propping up, repairing, plugging holes and cleaning off debris,” they were making plans for the beautiful new city they would build once the war was over. Even in the darkest hours of a military conflict, people were planning for a better future.

In the past year, many politicians have likened the fight against the novel coronavirus to a war, and those comparisons likely ring hollow to anyone unfortunate enough to have lived through an actual one. But there is still a lesson in that anecdote from more than 80 years ago, from another crisis, one much different and much worse than our own, from a world that hardly resembles the one we have inherited.

What better tribute could we — the survivors — possibly give to all those who perished in the plague year of 2020 than the creation of a more just, equitable and beautiful world? If people in the thick of a bloody civil war could plan for a better future, why can’t we?

The German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin was an eclectic thinker with many strange ideas, and perhaps most strange of all was his belief that we can change the past.

For most people, the past is settled business — what’s done is done, they say — but not Benjamin. Of course, the events of the past cannot literally be changed: a global pandemic was declared on March 11, 2020 and that will always be the case. But Benjamin thought the meaning of the past could be altered by what we do today.

There is no going back and saving the lives of Margaret Sader and all those Manitobans who died after her. There is no saving the millions of others who died around the world. We cannot prevent the catastrophes the pandemic unleashed. This is not a science-fiction novel.

And yet, we are not entirely powerless, either. It is our job to make sure the victims of the pandemic did not belong to a society that allowed the virus to kill what was best about our world. The defeat of the novel coronavirus need not be a pyrrhic victory.

We may not be able to change their fates, but we can make a difference to their stories, by rewriting them into a better narrative, by giving this story — this collective story that swept us all up in 2020 — a happier, more fitting ending.

If we want to, that is. If we have the moral fortitude and the political courage.

The tide of loss can be rolled back.

We can build anew.

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe