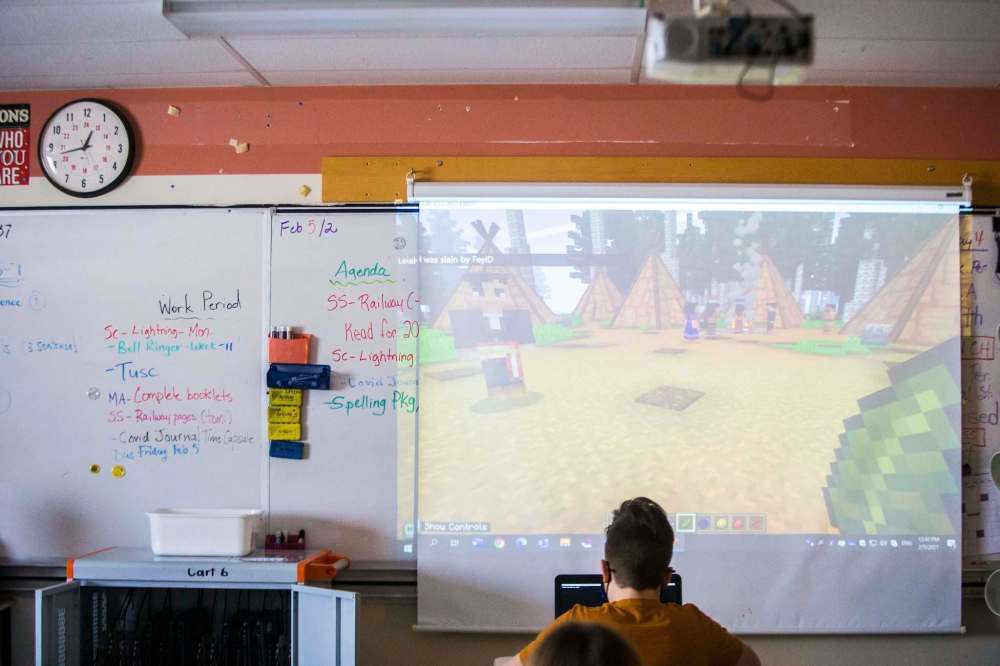

Game of their lives Winnipeg teachers work with Microsoft and Minecraft to create a pre-colonization pixelated Anishinaabe society populated by Indigenous educators, knowledge keepers and, hey... that's you, Mom!

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/02/2021 (1768 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In a forest abundant with birch trees, knowledge keeper Chickadee Richard greets students with a teaching about tobacco, known as semaa in Anishinaabemowin.

“Semaa is a gift of reciprocity. We give semaa to receive knowledge and healing,” Richard says about a practice that is traditional for Anishinaabe people, via a medium that is anything but.

The birch trees, much like the teepees, campfire flames and murky brown rivers that surround her, are pixelated.

And the elder from Sandy Bay First Nation? A video game version of Richard.

Welcome to Manito Ahbee Aki.

●●●

For more than a year, teachers in the Louis Riel School Division have been developing a Minecraft world that reflects how Anishinaabe people lived before European settlers arrived in in what is now known as Manitoba.

The video game, built in partnership with Microsoft Canada and Minecraft: Education Edition, is expected to launch later this month.

When it does, the team behind the project wants educators across the province — and world — to use it in their classrooms to teach history in a way that accurately and positively reflects Anishinaabe culture.

The objective of the game is for players to work together to build an Anishinaabe community of their own. Along the way, users learn traditional teachings about the elements from knowledge keepers as they build birch bark canoes, trade for the three sisters — corn, beans and squash — and hunt buffalo.

“Students have to understand there was a world view and a way of living and being that was sustainable, healthy, vibrant,” said Corey Kapilik, a Métis educator who is the principal of Marion School, during a development meeting in the fall.”

“If students understand the healthy community and understand how good things were here, then they can understand better (the) disruptions of residential schools, treaties, the Indian Act. Without that, we don’t have the same context.”

There’s no shortage of bears or birch among the unique pixelated flora and fauna in the game that reflect ecosystems in Manitoba, and all non-playing characters are based on real Indigenous teachers.

The Louis Riel division’s Indigenous Council of Grandmothers and Grandfathers, Indigenous education teachers, and knowledge keepers in the community have participated in countless meetings to ensure accuracy.

Accuracy down to the number of buffalo in the Manito Ahbee Aki herd: 30, which reflects the number of users who can play together at a time — since one buffalo can feed a single player’s family, exactness has been at the project’s core.

If one of the Indigenous community members didn’t approve of any part, it wasn’t included.

Richard gifted the name, Manito Ahbee Aki: an Anishinaabemowin phrase that translates in English to “the place where the Creator sits.”

“With more awareness, with games like this, (students) will have a better understanding of who we are. We’re not just somebody who came out of a textbook, or non-existent,” she said, adding Anishinaabe people still embody traditional ways today.

Upon initial download, players are assigned to clans and enter a virtual replica of The Forks, where they meet guides, gather resources and craft tools they will need later on.

Richard’s character dons maroon and black to represent being a member of the bear clan.

Players then travel to digital petroforms in Whiteshell Provincial Park in the second phase of the game, where they investigate the boulder outlines of creatures including beavers, moose and eagles made by Indigenous people.

It’s also where students may spot Sabe, a sacred character of the Anishinaabe people who embodies honesty and resembles Bigfoot. There are tobacco flags and red dresses hung in the trees in the scene.

Diane Maytwayashing typically provides teachings about the petroforms — which is where the Anishinaabe creation story begins — as well as the matriarchal society that once existed, on site, in ceremonies and during workshops.

Seeing her teachings translated into a video game left her teary-eyed.

“I’m just really excited. I never expected that we could come to this, to have Indigenous knowledge in a Minecraft game,” said Maytwayashing, who doesn’t recall learning a single thing about her people when she grew up in Winnipeg schools in the 1970s and ’80s.

In the final stage of the game, users create a community with gardens and teepees based on the knowledge they’ve gained.

Players have opportunities to click on extension activities, which include a series of videos of Maytwayashing, Richard and other knowledge keepers, as they play. The knowledge keepers recorded oral teachings and traditional songs to accompany the Minecraft activities.

●●●

Co-developers Chris Heidebrecht and Mark Lesiuk want the game to be a jumping-off point for discussions and, in a post-COVID-19 pandemic world, class visits from Indigenous knowledge keepers and field trips to different locations, such as the petroforms.

Both Grade 5-6 teachers, the duo believe Minecraft can be an effective teaching tool when curricular outcomes can be intertwined to take the game beyond just play.

They both already use Minecraft in their classrooms and run professional development training for colleagues in the division on how to use it effectively.

Calling it a “universal language” among students, Heidebrecht said the platform allows those who might not thrive with pen-and-paper activities to be leaders in the classroom.

“You need to trust your students to be experts in the classroom,” said Heidebrecht, who works at Minnetonka School.

Lesiuk, who teaches at Highbury School, echoed those sentiments, noting the game is not to be used as a babysitter for tired educators. “(Teachers) need to be part of a learning process that this game is going to give them,” he said.

Manito Ahbee Aki was designed to fit perfectly with the Grade 4-6 social studies curriculum, but it can be used at any grade level.

Colin Ciecko, 11, is among nearly 70 students who participated in the beta testing process and were sworn to secrecy about it until now.

“This is a world where you’re constantly learning about things you didn’t know,” he said.

The sixth grader said his favourite part of the “really fun” game is the buffalo hunt, during which players collect materials to guide buffalo off a cliff and harvest the animal.

Anishinabe elder Vern Dano’s character teaches players about the hunt.

“All of our animals are prominent, but the buffalo was very vital — not only for food sovereignty, but for community sovereignty. It was able to provide healthy food, it provided everything from physical, mental, emotional and spiritual supports to us as people,” Dano said.

Players will learn that buffalo cannot simply be killed; players must first show respect, he said.

Much of the game is about teaching students cultural values, so there is mutual understanding and better co-operation, he said.

●●●

Bobbie-Jo Leclair had purposefully never screened Disney’s Pocahontas in her home — but when her daughter was recently gifted Barbie doll princesses, the 10-year-old immediately gravitated to the only doll that looked like her, an Indigenous woman.

“How sad is it that the only image my daughter sees of herself in media is in images like Pocahontas, who, really, when she was 13 years old, had been sexualized and abused?” said Leclair, a Cree and French-Métis mother and Indigenous education consultant.

Manito Ahbee Aki challenges representations of the “noble savage” and “the defeated,” by showcasing Indigenous people in empowering roles, she said.

Leclair is a guide in the game. The uniform she chose for her character includes a ribbon skirt — an article of clothing she wears when picking traditional medicines and participating in ceremony.

When she showed her daughter, who is a daily Minecraft player, the 10-year-old immediately spotted her mother’s character.

“It was huge for her to see herself in this game that she loves, and for it to be such a positive thing,” Leclair said.

“She’s so excited to show her friends.”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, February 5, 2021 10:03 PM CST: Updates photo caption.

Updated on Friday, February 5, 2021 11:11 PM CST: Fixes typo.

Updated on Monday, February 8, 2021 4:56 PM CST: Fixes the correct spelling of Manito Ahbee in one sentence.

Updated on Wednesday, February 10, 2021 7:33 AM CST: Corrects spelling of Anishinaabe