Speak no evil Despite suspicion, the hockey community failed to protect the players Graham James was abusing

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/12/2020 (1821 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

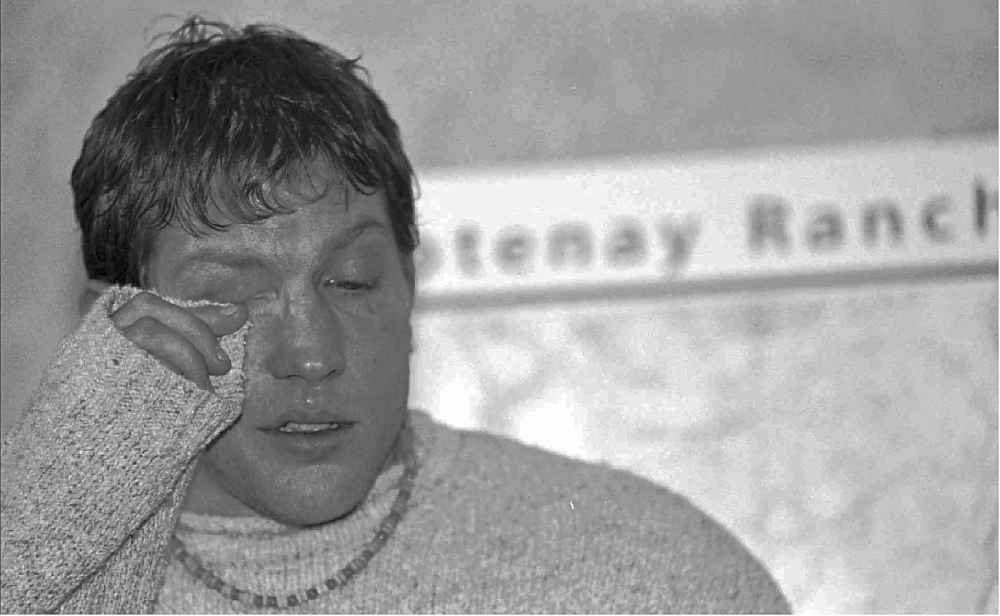

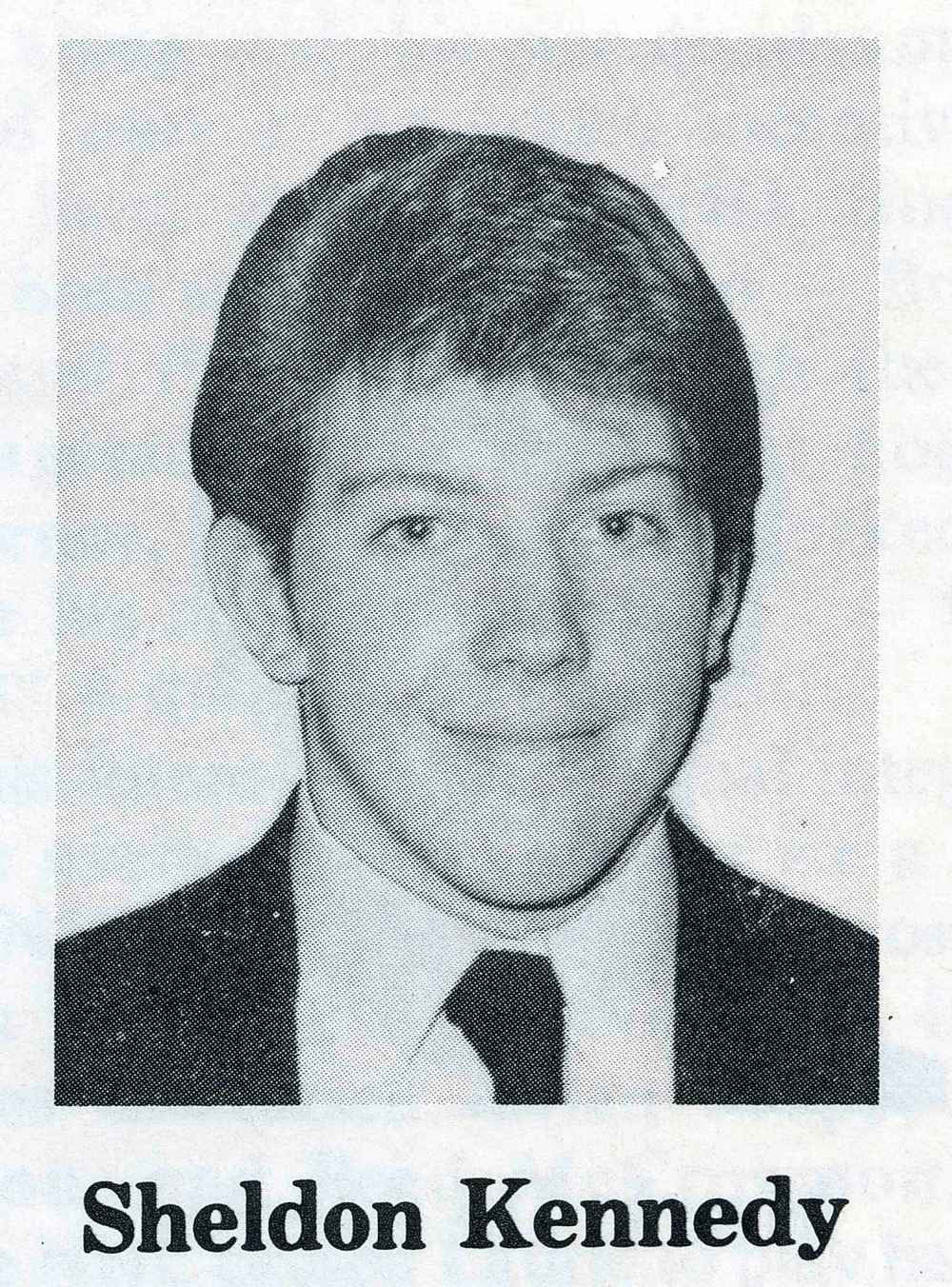

Brian Bell still remembers the way Sheldon Kennedy walked into the Calgary Police Service’s District 6 office nearly 25 years ago.

After being sexually abused hundreds of times by his former junior hockey coach Graham James, Kennedy was finally ready to share his painful truth.

About this series

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

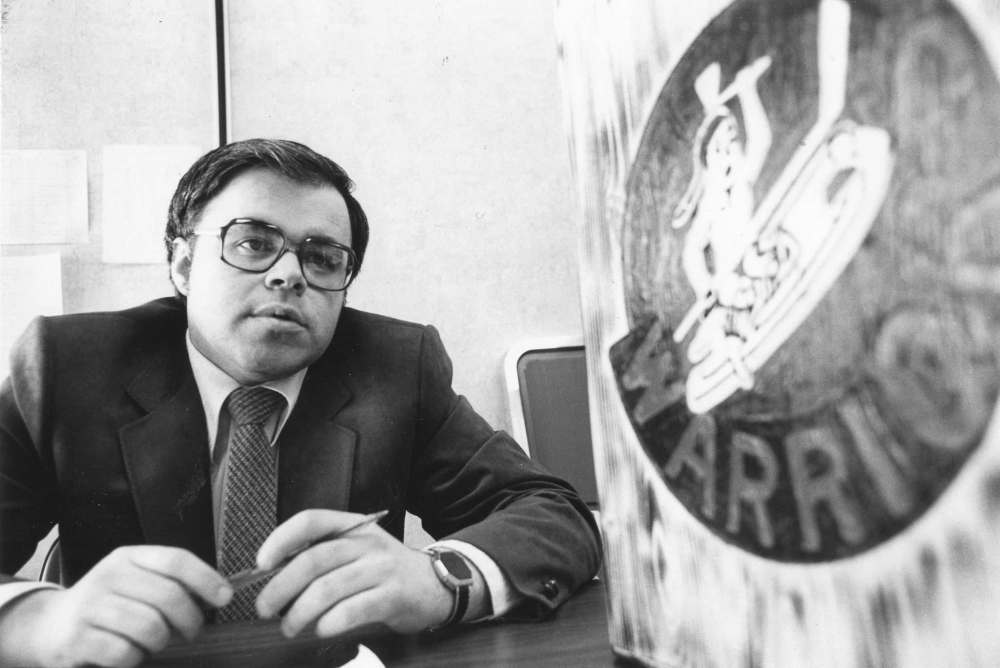

While a significant number of the assaults occurred in Saskatchewan, where he coached both the Western Hockey League’s Moose Jaw Warriors and Swift Current Broncos, the James scandal has always been a Winnipeg story.

James worked his way up through the ranks here — in Winnipeg minor hockey, the Manitoba Junior Hockey League and the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors.

It was with this backdrop that Free Press sports writer Jeff Hamilton began investigating James’ past, from his formative years growing up as an Air Force brat in St. James to his time as a substitute teacher in the St. James-Assiniboia School Division, and from his first foray into coaching minor hockey to his ultimate downfall.

Hamilton interviewed dozens of former players, childhood friends, educators and hockey colleagues and officials.

His investigation reveals an awkward teen who found confidence both in the classroom and at the rink, one that enabled him to embark on his trail of destructive criminal behaviour.

The investigation also paints a picture of complicity or, at the very least, wilful ignorance through all levels of the sport, which allowed James to abuse young players for years.

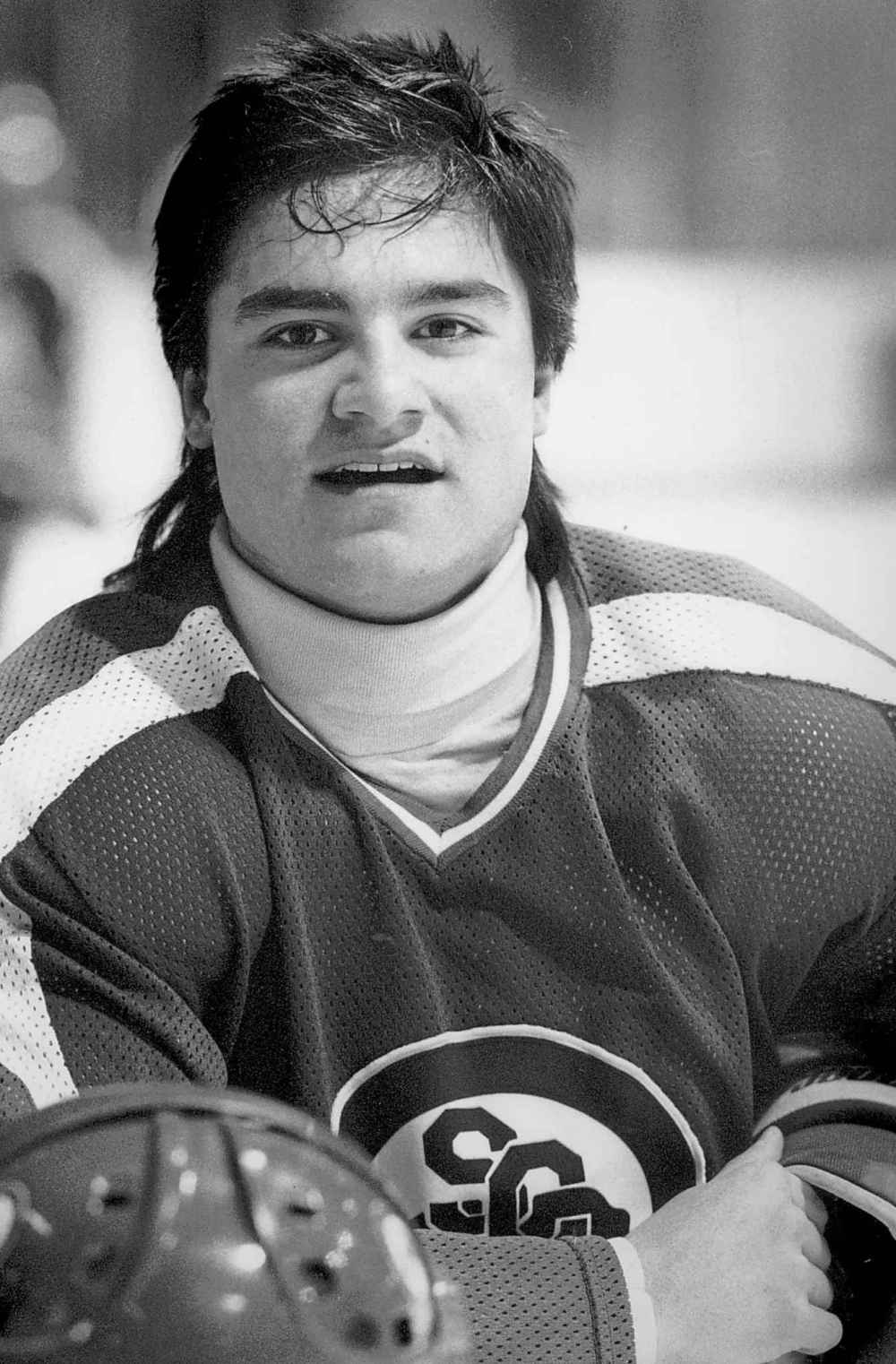

In total, James has been convicted of sexually assaulting five former players: Sheldon Kennedy, Theoren Fleury and Todd Holt have all publicly shared their ordeals; the identities of two others have been protected by publication bans.

However, police estimate the true number of victims is between 25 and 100.

While powerful institutions, such as the Catholic Church, and prominent individuals, including Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, have all had their moments of reckoning, there has been no equivalent to the #MeToo movement in hockey.

This Free Press investigation attempts to change that narrative by giving voice to victims and asking questions of those who knew or ought to have known what was happening on their watch.

Read the full six-part series, titled A Stain on Our Game.

“He was pretty fragile at the beginning and it took a number of conversations with us for him to relax,” Bell, a retired detective, says over the phone from his Calgary home.

“Nobody else had done what he has done in terms of coming forward and (facing) the stigma that was associated — and still is associated — with victims.”

Kennedy’s professional circumstances made it more challenging. He was in the public eye, still playing in the National Hockey League, and had been in and out of the league’s rehabilitation program for drug and alcohol abuse seven times.

Bell, who would become one of the lead investigators on the James case, said even the sight of officers made Kennedy uneasy. But he and Kennedy formed a level of trust, a connection that seemed to put him at ease.

He wanted desperately to explain what had happened, beginning when he was 14, but was extremely apprehensive; the thought of having to face his abuser, not to mention the fallout of accusing a widely respected junior hockey coach, weighed heavily.

What Kennedy feared the most, though, was that he wouldn’t be believed or, even more troubling to him at the time, people would think that he was gay. He had bristled at such inferences in the past; throughout his junior career, Kennedy was often the target of ugly homophobic slurs from opposing players — behaviour that suggested others knew something was going on with James.

“I told him that people have their own mindset, that they’re going to look at it through their own lens and they’re going to call it what they’re going to call it,” Bell says.

“But as more information comes out through time, people are going to see that you were a victim, that you were just a young kid and James took full advantage of his situation as a person of authority.”

Part 5 of a Free Press investigation examines the difficulties police faced in investigating the coach and the wall of silence that continues to surround the Graham James saga.

● ● ●

Bell lets out a long, deep sigh — one of a few over a 45-minute interview — before continuing.

“James had power over these kids and he coerced and belittled them. So there was no doubt in my mind that everything that happened to Sheldon was not consensual. You knew that, just from watching him and his gut-wrenching explanations of what he had to (deal with).”

All conversations took place at a “safe house,” away from the police station. Details of the abuse were hard to come by at first, but eventually Kennedy found comfort in opening up. He started to spill out everything he could remember.

“It was apparent really quickly into our conversations, with Sheldon going back over where he had been in terms of hockey with Graham James, and each incident that he talked about, each city that he talked about, each team that he talked about, opened up a broad spectrum of, ‘We’re going to have to reach out to a lot of people and we’re going to need a lot of help,’” Bell says.

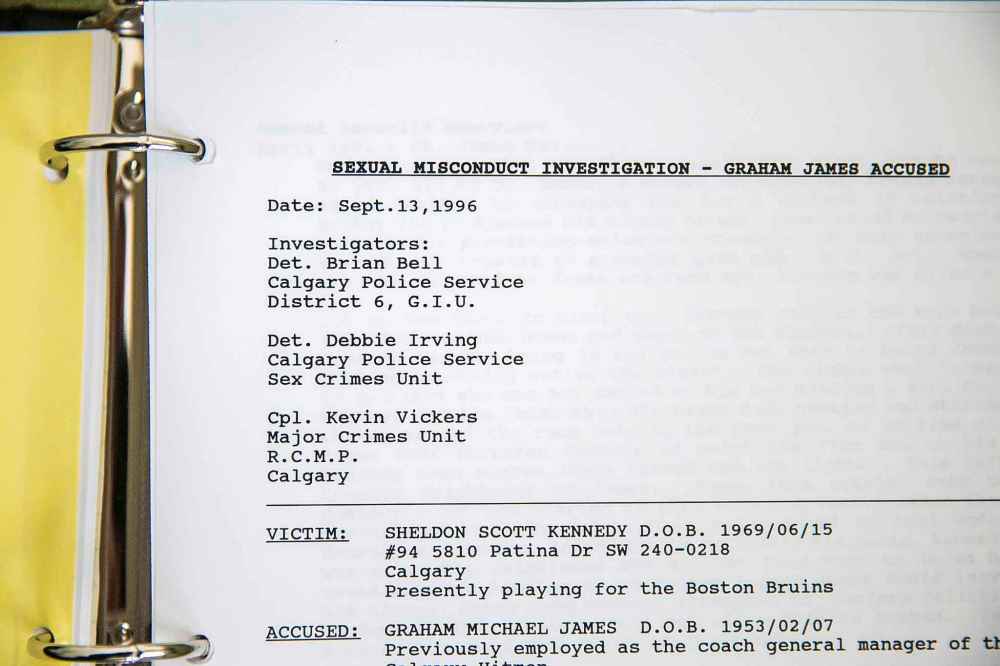

By Aug. 23, 1996, Calgary police had a full Kennedy-James timeline: from Winnipeg, where he was first abused, to Moose Jaw, then back to Winnipeg before settling in Swift Current. At each stop, James was his coach. The abuse ended for Kennedy only after the 1988-89 season, when he moved onto the pro ranks.

The next challenge was finding others who could either corroborate Kennedy’s story or reveal their own incidents of abuse.

Finding more victims was critical. Otherwise, it would be Kennedy’s word vs. James’ — a high-risk courtroom gamble Bell didn’t want to take.

Based on information from Kennedy, Bell says they estimated the number of potential victims to be “more than 25 and less than 100.”

Because the abuse had been spread out over many years, some of the players had moved on to careers outside of Canada, including in the U.S. and Europe.

Graham James coaching timeline

1977-78 — coach of the St. James Canadians’ bantam hockey team

1978-79 — coach of the St. James Canadians’ midget hockey team, scout for Western Hockey League’s Saskatoon Blades

1977-78 — coach of the St. James Canadians’ bantam hockey team

1978-79 — coach of the St. James Canadians’ midget hockey team, scout for Western Hockey League’s Saskatoon Blades

1979-80 — assistant coach of the Manitoba Junior Hockey League’s Fort Garry Blues (became head coach midway through season), scout for Blades

1980-83 — head coach of the Blues

1983-84 — scout, assistant coach of the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors

1984-85 — head coach of the WHL’s Moose Jaw Warriors

1985-86 — head coach of the Blues

1986-94 — head coach, general manager of the WHL’s Swift Current Broncos

1994-96 — part owner, general manager and head coach of WHL’s Calgary Hitmen

1996-97 — part owner of the WHL’s Calgary Hitmen

2000-01 — assistant coach of Spain’s national team

Geography wasn’t the only factor to consider. Though it was imperative investigators speak to as many players as possible, they also needed to do so in a sensitive and respectful way.

“And then from there it was just a matter of not letting this thing get too big, too soon,” Bell says.

That, however, would prove impossible.

Just weeks in, the Calgary Sun published a story that said police were investigating James. A month later, on Oct. 29, 1996, the Sun identified Kennedy as the alleged victim, ignoring a long-held media practice of not publishing a sexual-assault victim’s name.

As quick as some were to condemn James and commend Kennedy for his strength in stepping forward, there was also a flood of support for the coach from across the country that included former players.

And based on the number of people who refused to co-operate with police, Bell says he has no doubt that the public release of Kennedy’s name had an adverse effect on the investigation.

“Many said, ‘I know what you want and I’m not going to help you. I don’t want any part of this.’ We were getting that from a lot of players. Some were sympathetic and said, ‘Yeah, I kind of knew something was going on but I didn’t want to say anything because I could have been the one told to pack my things and go home if James thought I was ratting him out,’” Bell says.

“So there was a lot of fear, fear in terms of retribution from other players and fear that if they admitted to being abused they would be labelled a homosexual.”

”Many said, ‘I know what you want and I’m not going to help you. I don’t want any part of this.’”

Ultimately, investigators would only find one other of James’ victims willing to speak, but only if he remained anonymous. A publication ban has kept his identity hidden.

On Nov. 22, 1996, James was charged with two counts of sexual assault involving 350 incidents against Kennedy and the unnamed player.

There would be no trial. On Jan. 2, 1997, James pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 3 1/2 years in prison. To investigators, it was an insult.

“It’s a slap in the face,” Bell says. “To have this high-profile of a case, to have this high-profile of a situation, and then to have that meagre sentence attached to it was really frustrating.”

● ● ●

The language of hockey is often spoken in well-worn clichés. And it’s no different when it comes to the Graham James saga: “Everyone knew, knows or ought to have known something” is repeated over and over.

Yet decades later, few are prepared to say much of anything.

And asking those closest to James — friends and former hockey colleagues, men who hired him for coaching and scouting jobs, and their respective organizations, which include Hockey Manitoba and the Winnipeg South Blues — about what they knew or suspected is met mostly with silence.

Yet, even James knew his day of reckoning was coming.

Months before Kennedy went to the police, James got into an argument on the phone with Kennedy’s then-wife, Jana, who told him she knew what he had done.

James went into damage-control mode, calling other victims to silence them and alerting friends to shape the narrative that he was about to become a wrongly accused victim.

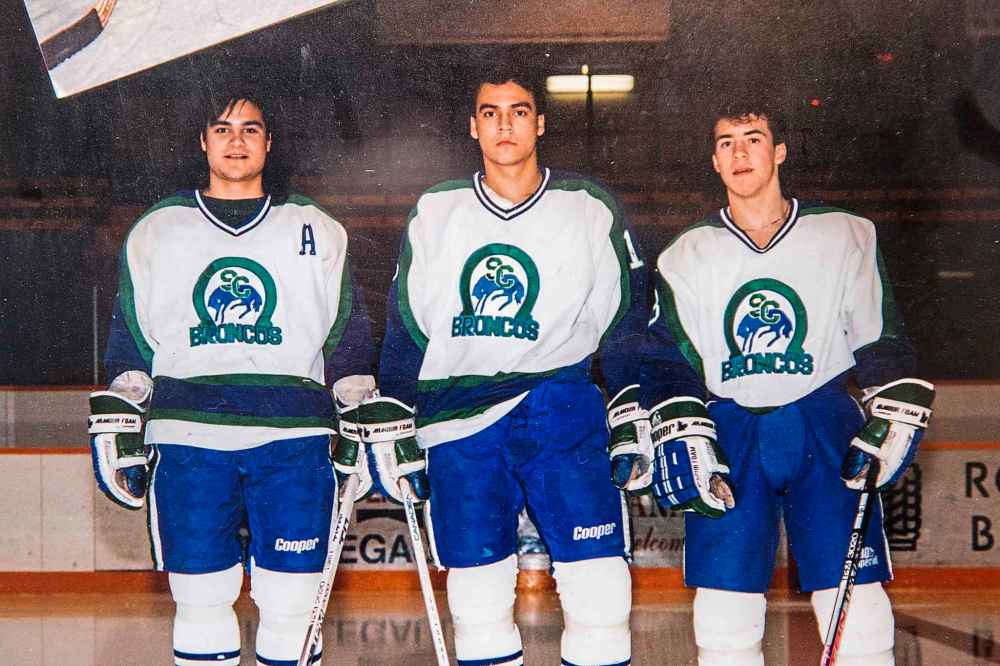

“He was basically warning me and… this was before Sheldon had come out, and basically, he was phoning to tell me to keep my mouth shut and not to say anything to the police,” says Lloyd Pelletier, a former Swift Current Bronco.

”Basically, he was phoning to tell me to keep my mouth shut and not to say anything to the police.”

It would be nearly two decades before Pelletier went to authorities to detail the abuse he suffered in the early 1990s. During a 2015 court hearing in which James was sentenced to two additional years behind bars, Pelletier called his former coach his “tormentor” and “demon.”

The argument that the organizations and people close to James ought to have known and had a responsibility to alert authorities was the basis of a civil lawsuit filed in 1999 by an unnamed victim of James.

The long list of defendants included the Western Hockey League and the WHL teams where James coached, along with several of their representatives, the Manitoba Amateur Hockey Association, the Manitoba Junior A Hockey League, the Manitoba Junior Hockey League and the Winnipeg South Blues (formerly the Fort Garry Blues).

The statement of claim alleged that the Manitoba organizations knew or ought to have known James was sexually assaulting and abusing his players from at least 1971, that they failed to take steps to prevent further abuse, and that they continued to allow James to coach, manage and trade for players that he was sexually assaulting.

Similar allegations were levelled against the Blues organization, which was also accused of suppressing information James sexually assaulted, molested, harassed and abused players.

The lawsuit was settled before trial, so the allegations were never addressed in court. What is known, however, is Hockey Manitoba never investigated when the Kennedy-abuse suspicions surfaced, or 14 years later, when more allegations emerged, according to multiple people connected to the organization during that time.

George Ulyatt was the longtime manager and, later, part-owner of the South Blues, beginning in 1984. He also became president of the Manitoba Amateur Hockey Association in May 1996 just as the James scandal was about to break. His new role would require overseeing the MAHA’s response to James’ assaults.

Ulyatt, a Winnipeg lawyer, had a long association with James, both as a hockey colleague and friend. It was James who hired Ulyatt to be the Blues’ general manager when James was the team’s coach in the early 1980s.

It was Ulyatt, by then part-owner of the Blues, who hired James to be the team’s coach in 1985 after he left the Moose Jaw Warriors. That season, the Blues paid James for Kennedy to live with him and looked away as Kennedy rarely attended school.

Their friendship included summer road trips to P.E.I. to visit James’ family. Multiple attempts to speak to Ulyatt were rejected.

How Ulyatt was impacted by the scandal in his official capacity with the MAHA and the South Blues and how he responded is left to fragments of conversation gleaned from interviews with others.

A former Winnipeg coach who used to work in the MJHL said he suggested to Ulyatt during a meeting in Ulyatt’s law office in 1995 that James was making advances on kids. Ulyatt seemed shocked by the suggestion at the time and ultimately dismissed it, the coach said earlier this year.

“He mentioned to me after this all came out that he was sorry he didn’t listen to me,” recalls the coach, who didn’t want to be identified.

“Whether he was covering his ass or not… it’s hard to believe George didn’t know something.”

”Whether he was covering his ass or not… it’s hard to believe George didn’t know something.”

When Greg Gilhooly set out in 2015 to write a book on how James sexually abused him over a period of three years, he wanted to talk to those who were close to James. That included Ulyatt, who was also a friend of Gihooly’s dad through MJHL connections.

Ulyatt told Gilhooly, a Toronto lawyer, he wasn’t sure he wanted to “open a chapter of my life that has caused me significant issues.”

Three years earlier, Gilhooly had emailed Ulyatt asking him why he didn’t attend James’ sentencing in Winnipeg for assaults involving Theoren Fleury and Todd Holt.

Ulyatt replied a day later, opening the message by referring to Gilhooly as a “celebrity,” in reference to a feature story written about him in the Globe and Mail, where he shared his story and publicly released his victim impact statement.

“As for the court appearances, I wanted to be as far away as possible,” Ulyatt wrote. “The last go round (Sheldon) I was attacked by some media as I ought to have known, and as a result did receive some odd (!) calls at home (read threats).”

In his book I Am Nobody: Confronting the Sexually Abusive Coach Who Stole My Life, Gilhooly describes how he first met James as a teenage goalie for the St. James Canadians and how he was manipulated for years until the assaults stopped after he left to study at Princeton University in New Jersey at the age of 18.

The insight Gilhooly sought from those close to James never came. Instead, he was told he was never abused, a James-driven narrative that still exists today.

“Just take a step back and look for the perspective of, how do they know? And yet they are so certain in what they say?” Gilhooly says.

An affidavit filed Dec. 7 by an unnamed player as part of a new lawsuit against the Canadian Hockey League also paints a damning picture of the hockey life swirling around James in the early 1980s in Winnipeg.

The unnamed player says in his affidavit he was aggressively pursued by James to join the 1983 Winnipeg Warriors, a now-defunct WHL club. Upon his arrival, he was billeted in the home of Edmund Oliverio, a convicted sex offender who then repeatedly tried to sexually pursue the player.

“I think it is shocking that the team would billet me with a convicted pedophile, chosen by another pedophile and that the team did not believe me when I complained,” the player says in his affidavit filed in Ontario Superior Court.

”I think it is shocking that the team would billet me with a convicted pedophile, chosen by another pedophile and that the team did not believe me when I complained.”

Members of the team’s organization also turned their backs to horrific hazing that he and other rookies endured that season, he says.

Tom Thompson was the Warriors general manager that year and had hired James as the team’s head scout and assistant coach.

When he heard of the affidavit’s allegations, Thompson says he was sorry for the player but he had no idea that was going on. He also denies the player told him he was being sexually pursued by his billet.

Thompson, a longtime friend of Ulyatt’s dating back to when the two were classmates together at law school, and who would go on to a long career in the NHL — including as the director of amateur scouting for the Calgary Flames and the assistant general manager of the Minnesota Wild — has remained a friend of James through the ensuing sex-abuse scandals.

It’s a friendship that many others in hockey have questioned, given Thompson’s prominent role in the game.

Thompson doesn’t expect people to understand. He says his motivation is selfless and it’s no different than the volunteer work he does when he travels to Africa with his church or with organizations such as the John Howard Society.

“Unless they’re in for life eventually they’re coming back out on the street and they can be potential threats to myself, my loved ones and our property…it might be in my best interest to try and see what I can do to keep as many of these people on the beaten path that you can,” Thompson says.

Though he doesn’t condone his behaviour, Thompson dismisses the notion James used the game exclusively as a vehicle to abuse players. He also disputes James preyed on a much larger number of players, as police investigators believe.

When the scandal broke in 1996, James told Thompson that he would respect his decision if he walked away.

Thompson, upon a time of reflection, returned and set out three conditions for their friendship. “One, is that you stop what you’ve been doing or any other criminal activity. The second one is I said I’m not expecting you to make a mea culpa to me; in fact, it’s probably best that I don’t know all of the things from all the people. But I don’t want you to lie about anything.

“And the third thing is you have to get professional help.”

James, Thompson says, has continued to meet those conditions.

Former Bronco Kimbi Daniels is a rare exception among those who still call James a friend. He speaks freely about his three seasons in Swift Current that began in the fall of 1988.

Daniels also doesn’t expect people to understand why he still occasionally talks to James. And he doesn’t regret writing a reference letter for James’ sentencing hearing for abusing Kennedy, who was his roommate during his first season in Swift Current.

“For me, and it’s kind of why I guess some people would think I’m sticking up for Graham, but it’s my relationship that I have with him,” Daniels says in a phone interview from Anchorage, Alaska, where he now lives.

“If one of my best friends, God forbid, did something horrible, it wouldn’t change from the standpoint of, I would still be his friend, most likely. If it was my son or someone directly connected to me, obviously my feelings would be different. But it wasn’t, and so it’s a real awkward situation for me sometimes, because I really like Sheldon. I think the world of him, especially for what he’s gone on to do post-hockey.”

”People, they hear the story and they think, ‘Man, that’s just terrible. How did they let this happen?’ It’s a whole different perspective when you’re there playing and living it.”

Looking back at his time in Swift Current, Daniels says he would come to learn after Kennedy had left the Broncos that something was going on between his former roommate and the coach. What he knew and how he interprets the information has evolved over time. But he remains committed to the belief that if you weren’t there, then you can’t truly understand the situation.

“It’s hard when you know, to an extent, what’s going on to talk about it publicly, because if you didn’t know the whole story and if you weren’t involved on a day-to-day basis, more people, they hear the story and they think, ‘Man, that’s just terrible. How did they let this happen?’ It’s a whole different perspective when you’re there playing and living it.”

While James preyed on some players, he was up front about his sexuality with others. He told Daniels prior to the start of his third season that he was gay and asked if the recently NHL drafted star forward would be interested in a relationship.

Daniels made it clear he wasn’t, and what followed was a rocky season. At one point, Daniels threatened to reveal James was having sexual relations with players, but they made amends when Daniels was traded during the off-season.

Though they still occasionally talk, he’s not sure James has come to grips with what he did.

“I don’t ask him if he’s sorry, but he doesn’t speak like he’s sorry that it happened,” Daniels says.

“I think he still feels like there’s somewhat of a two-way street involved and that they did their part to allow it to happen.”

●●●

When Don Smith first heard an NHL player had come forward accusing James of sexual abuse, he knew it could only be Kennedy.

He simply connected the dots from what he had witnessed as a 21-year-old linesman in the MJHL in the early-1980s when James was the coach of the Fort Garry Blues.

“I’m a linesman (in) a St. James Canadians and Blues playoff game and the Canadians were just giving it to the Blues players. They were saying, ‘What is Graham going to do to you in the showers afterwards?’” Smith recalls.

“And that wasn’t the only comment, there were others that were more disgusting than that.”

When James returned to the Blues for the 1985-86 season following his demotion in Moose Jaw, Smith found it odd that Kennedy also returned.

Kennedy had played 16 games with the Warriors the previous year and was being heralded as the WHL’s next star. Instead, he was living with James and playing in an inferior league. And the homophobic comments on the ice continued.

Looking back years later, Smith says it is hard to believe people in positions of power around James could not have heard the same things. And if players and coaches were openly accusing James of having sex with members of his team, then that should have been enough to at least raise some concerns.

“Everybody in junior hockey in Manitoba knew that something was going on. Nobody knew what it was, specifically, and I don’t know who had what knowledge, but something was going on,” Smith says.

”Everybody in junior hockey in Manitoba knew that something was going on.”

In 1996, Smith was the natural choice for Hockey Manitoba’s first player advocate, a primarily volunteer role. By then he was a decade into his social-work career and had experience working with sexual predators in the prison system. He had also been officiating hockey for years, making his way up to referee-in-chief.

One of the organization’s first moves was to set up a private toll-free help line in Smith’s office for players to report abuse. Smith had also been tasked with developing a policy to protect players. He says Ulyatt explained what he hoped to accomplish when he approached Smith about the role.

“When (Kennedy’s name was revealed publicly), George said to me, very clearly, ‘I feel horrible. I hired (James),’” Smith says. “And that’s why he and I put together the player-advocate plan.”

In an interview with the Russell Banner in January 1997, Ulyatt said Hockey Manitoba has an obligation to provide counselling and treatment if a player had been a victim of abuse as a result of being involved in the organization’s program.

“We can’t undo what has been done, but we can ask those who have suffered to come forward to see whatever assistance they deem to be appropriate for them,” Ulyatt said.

Smith put in long hours developing Hockey Manitoba’s plan. It was critical to develop an in-house program, he says, because the James abuse began in the province. In the meantime, he waited for the phone to ring.

Smith fielded five to 10 calls a day. Not one involved James. Instead, it came as a shock to Smith to hear a number of older, serious allegations about former teachers who had once taught in the southwestern corner of the province and were connected to Hockey Manitoba.

”We can’t undo what has been done, but we can ask those who have suffered to come forward to see whatever assistance they deem to be appropriate for them.”

They included Hockey Manitoba executive Jack Forsyth, who was suspended, and then fired, as principal of Hartney Collegiate for abusive behaviour against high school students, and Danny Cassils, a longtime referee, who was convicted of sexual offences involving students in Hartney, and later, Warren. The same year Forsyth was fired, in 1993, the MAHA named him volunteer of the year.

Smith continued to work on his policy, which he believed was stronger than ones being developed by other sports governing bodies. His proposal included in-person training courses, seminars with parents and coaches and a more defined process for reporting abuse.

He was deeply disappointed when the organization — now with Forsyth overseeing the project as Ulyatt shifted his focus to the World Junior Hockey Championship in Winnipeg — turned its back on his proposed policy and adopted Hockey Canada’s “watered down” program that was “insufficient for what was needed at the time.”

”As horrendous as the Graham James situation was… there was some good that did come out of that.”

Current Hockey Manitoba executive director Peter Woods disputes the notion Hockey Canada’s response was inadequate. It developed the Speak Out! program, which has evolved into the Respect in Sport program and is now mandatory for parents and coaches involved in every sport under the Sport Manitoba umbrella.

“As horrendous as the Graham James situation was… there was some good that did come out of that,“Woods says.

“Hockey Canada, certainly, I think has probably been one of the leaders because of that incident, in regards to bullying and sexual abuse and harassment and things of that nature.”

●●●

Paul Buchanan can’t shake a memory from his sister’s wedding in late 1996.

A guest who had connections to James and the MJHL started to ridicule Kennedy, who had just gone public with the abuse he suffered.

“He said that Sheldon was a liar… He just went on and on,” Buchanan says. “It made me feel sick. The company line was Sheldon was a liar, a drunk and he was crazy.”

”The company line was Sheldon was a liar, a drunk and he was crazy.”

Buchanan was confident that wasn’t true.

When Buchanan showed up at the Fort Garry Blues’ camp in the fall of 1980, James already had him on his radar. But after he repeatedly spurned James’ grooming, Buchanan quickly fell from golden boy to errand boy tasked with menial chores.

Although he was never sexually assaulted by James, Buchanan says he was subjected to deliberate and calculated mental abuse over two seasons. The short-term damage derailed his aspirations to play at Princeton University, from which he already had a letter of acceptance. The long-term damage is something he still struggles with today.

When allegations involving Theoren Fleury, Todd Holt and Greg Gilhooly surfaced in 2010, he knew he had to confront his own demons and began his own investigation.

“I called pretty much everybody, because I felt we let down Sheldon Kennedy the first time and had to listen to everybody say he was a liar,” Buchanan says. “So when this came around again I didn’t think anybody was going to help and I probably knew as much about it as anybody, because I felt I had been targeted.”

Buchanan’s primary focus wasn’t to find and encourage new victims to come forward, although he’s positive they exist. Instead, it was to shine an uncomfortable spotlight on people who were closest to James in Winnipeg.

He typed out his own personal account and submitted the letter to police, who subsequently interviewed him several times.

Buchanan described how his dad, who is now deceased, encouraged him to continue playing minor hockey when it became clear James was trying to groom the teen.

He described how James would take 15-year-old recruits on hockey trips and watch them play in hotel pools; how James would take players on trips to watch baseball games in Minneapolis; how James, then in his late 20s, would playfully chase players around his apartment; and how, after Buchanan left the team in 1982, their paths crossed one last time months later at a movie theatre.

“Graham flew out of the theatre in a boyish glee. He was with some young boys who appeared to be around 14,” Buchanan wrote in his letter to police.

“They were friendly boys and I was introduced to them. They were from the country, two wearing Elkhorn jackets, and the other, I am not sure, but it might have been Theoren Fleury. I felt that I had caught Graham at something, as he immediately stopped laughing and joking upon seeing me.”

Back then, Buchanan had never really heard of Gilhooly, beyond a recollection of him being a talented goalie in St. James. He didn’t know a 15-year-old Gilhooly was secretly meeting with James — weekly sessions that began with various training exercises and ended with James sexually abusing his young pupil.

Now as adults, Gilhooly asked Buchanan to reach out to people on his behalf. Both were equally frustrated that no one close to James was willing to speak up, to take the side of the victims.

“I was contacting people so that they could finally be proactive and not let Graham call the shots,” Buchanan says.

At one point in the fall of 2010, Hockey Canada reached out to Buchanan. In a phone call, Glen McCurdie, now senior vice-president, insurance and risk management, who eventually handled the out-of-court settlements for James’ victims, had suggested to him that the national organization was duped during the original James case.

“He said during the Sheldon Kennedy scandal they believed Graham and that he got all these character witnesses and that they were thinking that Sheldon Kennedy made it up,” Buchanan says.

“He said in 1996, it took them by surprise because they had been going along with the story… that this Sheldon Kennedy guy was a fake. So they were taken by surprise… when Graham admitted to it. Finally he had admitted to it. He talked as if he was controlling the courtroom… all up to the point he had got character-witness statements from everybody.”

They were taken by surprise… when Graham admitted to it. Finally he had admitted to it.”

McCurdie declined requests to be interviewed.

Unlike Hockey Canada, Hockey Manitoba was not actively seeking out victims, nor has it ever, according to multiple people connected to the organization.

However, in at least one instance, Hockey Manitoba was on the hook for $50,000 for its share of a Hockey Canada settlement to a victim connected to the province.

Meanwhile, Buchanan’s efforts caught the eye of Hockey Manitoba’s executive director Peter Woods. In a chance meeting at a hockey game in late 2010, Woods mentioned he had heard a rumour involving James just as he was beginning to coach minor hockey.

●●●

In the summer of 1978, James took three of his St. James Canadians bantam hockey players camping for a weekend in Dauphin River.

That team, which would play the following year in the inaugural national midget championship — the Air Canada Cup — with James behind the bench, was led by star forward Bruce Eakin. Eakin would go on to be a late-round selection of the Calgary Flames in the 1981 NHL draft.

“Yeah, he had some sort of an obsession, and not just with me, but with other guys, too,” Eakin says in a phone interview from his Florida home. “I think he thought that we could stick together and if I made it, then he would make it.”

That obsession crossed the line on the camping trip.

For sleeping arrangements, they were crammed into one tent. Hours into the first night, Eakin noticed a hand reaching inside his sleeping bag. James had positioned himself directly next to Eakin and he was trying to unbutton a flap on the back of his underwear.

Eakin, then 16, immediately shut him down.

“I was looking right the f–k at him,” he says. “I got up and said, ‘This ain’t happening to me. I don’t know what you’re trying to do.’”

The boys retreated to the car but then decided to get James to drive them home immediately. He begged them to stay.

“What he wanted to do was manipulate me to make sure I didn’t tell my parents or my older brother,” Eakin says. “We just told him we’re getting the hell out of here and you’re either coming or not.”

”What he wanted to do was manipulate me to make sure I didn’t tell my parents or my older brother.”

It was Eakin, who didn’t have a licence, who got behind the wheel for the four-hour ride home in the dark, with a distraught James slumped in the back seat desperately pleading for them to stay quiet.

“We had an all-star team at the time. We were going to the Air Canada Cup that year I think — it’s hard to remember — but he was all, ‘You can’t tell these people’ and, ‘You’ll ruin the team,’” Eakin says. “I said, ‘Good luck, pal.’”

When George (Red) Eakin heard what had happened to his son when they got back, his first instinct was to confront James.

“My dad went ballistic, he’s going, ‘We’ve got to go over there,’” Eakin says. “And my mom basically said, ‘You’ve got to settle down, George. We’ve got to figure this thing out.’”

A few days after the incident, Eakin heard a knock on his bedroom window. It was James.

“He wanted to apologize. He said he was sorry, and that I got it wrong. He said he needed help,” Eakin recalls, though he can’t remember what exactly James needed help with.

“Then my dad opened the door and saw him on the other side of the window. He tried to chase him down, but Graham was gone.”

Days later, his older brother Butch confronted James, telling him never to come near the family again. Despite the anger at the time, the Eakin’s family and James would eventually make amends.

After Kennedy went public, Eakin wrestled with thoughts of whether his family could have prevented James from harming others.

“What bothered me later — and my father a lot, too — is what happened after that. Could we have stopped it? I don’t know,” Eakin says. “He went to prey somewhere else and that’s, I think, what bothered my father for a while. When this stuff started to come out he really looked deep inside himself to say, ‘Maybe I could have done something then.’”

”Could we have stopped it? I don’t know.”

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to look at the situation and place blame. Back then, the public was much more uncomfortable confronting sexual abuse. No one wanted to be associated with such horrible claims.

Eakin believes his father initially went to the police, though he can’t say with certainty. (George Eakin died of cancer in 2010 at the age of 80.) Winnipeg police did interview Bruce Eakin in 2010 after Fleury’s revelation, but it never went further than that. Eakin, himself, has never viewed himself as a victim.

More troubling, though, is that George Eakin was a St. James School Division trustee and had a duty to report what happened. After all, James was a substitute teacher in the division.

“I’m really, really shocked that in George Eakin’s capacity on the school board — and at that time he wasn’t the head of the school board but he controlled a lot of it — how he would allow Graham to teach kids,” says a former teacher, who worked closely with and respected the elder Eakin.

”I’m really, really shocked that in George Eakin’s capacity on the school board… how he would allow Graham to teach kids.”

“But also at that time, what happened was unheard of and it would have been extremely difficult to come forward. Still, I can’t imagine it would have been hard to pull (James) off the sub list.”

Eakin didn’t offer an opinion on his father’s role as a school trustee but he does believe he considered the consequences of exposing James and how it might affect his son’s promising career.

“I think my dad would have agreed at that time, that because of what was happening with myself being basically at the top of the league every year… I think he didn’t want to upset the apple cart a little bit,” he says.

“But there was nothing that really happened until — that I know of, anyways — Sheldon and those guys started saying things. Prior to that, no investigation would have gone very far.”

●●●

NHL star Thereon Fleury released details of the abuse he suffered in his 2009 autobiography, Playing With Fire. Shortly after, he filed an official complaint with the Winnipeg Police Service.

Ken Ehmann was tasked with leading the police investigation. Colleen McDuff, who was the Crown prosecutor at James’ subsequent sentencing, says Ehmann and his team were exceptional in their search for justice.

“They went above and beyond, simply amazing,” McDuff says. “They just went, like, full out.”

When first reached by the Free Press, Ehmann was hesitant to provide much insight into specific details of the investigation. He said there were court orders attached to the case and he didn’t know what he could legally discuss.

He spoke in general terms about some of the challenges the investigators faced, but declined to elaborate.

“It wasn’t just a couple years. We’re talking decades,” Ehmann says, referring to James’ abuse. “There were a lot of people, and not only the victims, but there were a lot of people who were affected by this.”

“There were a lot of people, and not only the victims, but there were a lot of people who were affected by this.”

Ehmann knew some of the potential victims, along with others who were involved in the city’s hockey community.

He grew up in the North End and played hockey at the time James was starting to make a name in coaching; he remembers James’ affiliation with the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors and attending camps that he was associated with.

He thinks his close connection to the local hockey community helped build trust when he approached people for the investigation. And he didn’t want to do anything to damage it.

“I spent a lot of time — I’m going to use the word ‘protecting,’ for lack of a better word — I spent a lot of time doing that and it’s… it was tough,” he says.

”Some have buried it and they don’t want to talk about it and they don’t want their name ever brought up and I get it. People have to recover on their own.”

“If you’re in the hockey community and know people in the hockey community, that’s how people would talk to you. It took me a while, and it took everybody asking around if they wanted to talk to me and it took me some time travelling to talk with people.”

As with the Calgary investigation in 1996, there would have been no pressure for anyone to pursue charges or share their story. But it’s also no secret there are more victims out there, many of whom are still struggling.

“It’s got that stigma to it and it’s tough for people to talk about,” says Ehmann, who spent six years with Winnipeg’s sex crimes unit.

“Some have buried it and they don’t want to talk about it and they don’t want their name ever brought up and I get it. People have to recover on their own.”

●●●

James originally faced nine sex charges, spanning the years from 1979 to 1994.

The charges involving Gilhooly were stayed as part of a plea deal, leaving James to plead guilty to two counts of sexual assault accounting for hundreds of incidents of abuse against Fleury and Holt.

The decision to stay the charges associated with Gilhooly continues to trouble McDuff.

They were not stayed because James didn’t have sexual encounters with him, but that he claimed they were consensual, McDuff says, revealing for the first time what was happening behind the scenes.

“What the situation came down to is James was prepared to plead guilty to everything related to Theo and with everything related to Todd Holt, “ she says. “But he was adamant that his relationship with Gilhooly was consensual.

“Which, of course, I didn’t believe.”

McDuff says it was a balancing act between going to trial with victims who were very raw emotionally and might struggle to share their experiences, or ensure a conviction by having him admit to abusing Fleury and Holt. It was a decision she didn’t take lightly.

“This is something that still bothers me to this day,” she says. “It was probably the most difficult decision I had to make in my entire career.”

Fleury wasn’t in Winnipeg for the sentencing hearing. In a symbolic gesture to show how far he had come in his healing journey, he read his statement at a media conference in Vancouver.

“At a young and very impressionable age, I was stalked, preyed upon and sexually assaulted over 150 times by an adult my family and I trusted completely,” he began.

Fleury, who grew up in Russell, went on about how as a young kid he would eat, sleep and breathe hockey — a deep passion that James exploited to manipulate him. He spoke about how he was “completely under Graham James’ control” and that because he was a child at the time, he lacked the “emotional skills, the knowledge or the ability to stop the rapes or change my circumstances.”

He said James’ abuse was behind his descent into “drug addiction, alcoholism, and addictions to sex, gambling and rage. And no matter how many NHL games I won, or money I made, or fame I gained could dull the pain of having been sexually abused by Graham James.”

”No matter how many NHL games I won, or money I made, or fame I gained could dull the pain of having been sexually abused by Graham James.”

Fleury said it was only after an emotionally crippling night in the New Mexico desert, where he shoved a gun in his mouth and placed a finger on the trigger, that he finally found the courage to push back.

Unlike Fleury, Holt was sharing his pain publicly for the first time.

He talked about how he forever changed as a person after James stole his innocence, motivation and soul. Holt said he will always be left picking up the pieces of his life.

“My mother saw the kind, loving child she gave birth to turn into a cold, self-sabotaging shadow of a man. My dad lost his hero; his hockey star had lost it all,” Holt said, as a steady stream of tears flowed down his cheeks.

“My siblings watched as I went further into my destructive habits and distanced themselves from their baby brother. My wife lost her husband and the life we shared together after our marriage came and went, too.

“My two incredible sons (and my life’s most precious gifts) lost their Daddy. How could I protect them and give them the life they deserved when I had nothing but shame and disgust for the person I saw in the mirror? All of this because of what happened to me in the ‘care’ of Graham James. I did not choose to be a victim of this monster’s manipulative, abusive ways.”

”I did not choose to be a victim of this monster’s manipulative, abusive ways.”

McDuff remembers Holt as the “sweetest, most gentle person. I don’t think there was a dry eye in that courtroom when he read his victim-impact statement.”

It would take nearly a month before Justice Catherine Carlson was ready to deliver her verdict. And as she read her judgment, handing James a sentence of just two years, a wave of disappointment spread across the courtroom. (The sentence was increased to five years following the Crown’s appeal.)

“He controlled what would happen with their hopes and dreams of playing professional hockey. He could make or break them. He told them that,” Carlson said.

“Mr. James could essentially do what he wanted to do to them, and could rely on their compliance and silence, because he controlled whether they would get the chance at what they really wanted or would have their dreams crushed.”

There were other factors, though, that favoured James. The judge noted his previous sentence, that he had not re-offended since 1994, had received treatment, surrendered to police, faced intense public scrutiny and pleaded guilty to crimes he seemed to be genuinely sorry for committing.

Carlson added that there is no sentence that the victims, and many members in the public, would find satisfactory, but also made clear “that the Canadian criminal justice system is not one of vengeance.”

For the victims, it was another gut-wrenching result. Those who were abused struggled with the fact that James could be out of prison in fewer than 16 months, with good behaviour, despite admitting to hundreds more assaults.

●●●

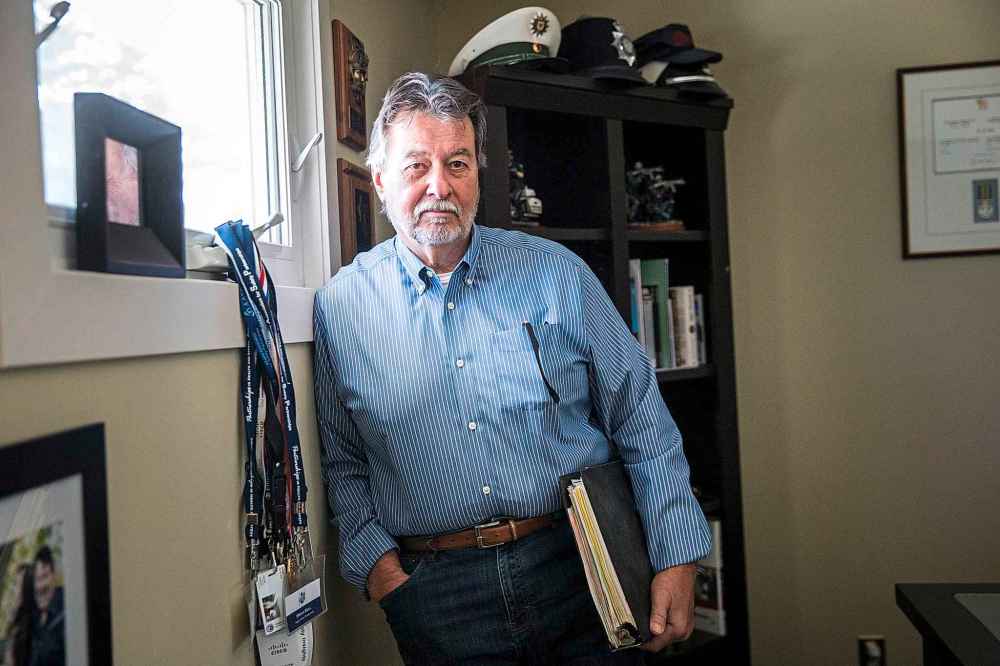

In poker parlance, Brian Bell has a tell.

The retired Calgary police officer’s recounting of the six-month investigation following Kennedy’s revelation is precise and detailed.

But when asked about disturbing allegations that never made it to court, he responds with a “no comment.”

It’s the same response when he’s asked what he thinks James’ friends and hockey colleagues knew. Without saying more, his frustration with the level of co-operation police received remains clear years later. And he has little patience with those who supported James when he was first convicted.

“I don’t get people,” he says. “Maybe there were people in Graham James’ circle that think he’s a well-meaning individual and he had problems and he preyed on young boys for a period of time but now he’s remorseful and he’s going to be better.

“Maybe I’m just looking at it from a jaundiced point of view, after spending, by that time, on the police department for 24 years, dealing with the worst of society and not trusting a lot of what people say because a lot of it is self-serving.”

When Bell and two other officers visited James at the maximum-security federal prison in Edmonton shortly after he had been arrested, they were stonewalled for hours. He denied any wrongdoing and would admit only that he was close with a number of his former players.

“He said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. I mean, I had a relationship’ — he called it a relationship — ‘with a couple boys and that’s all,’” Bell recalls. “But we knew full well that wasn’t the case.”

There was a moment during another interview that James made it clear he didn’t care much for being labelled a “serial sexual predator.”

“And I said to Graham, ‘Well, tell me I’m wrong,’ and I threw a number at him. I said, ‘I know of at least this number of kids that have been victimized — tell me I’m wrong,’” Bell says.

“And he just shut up.”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

After a slew of injuries playing hockey that included breaks to the wrist, arm, and collar bone; a tear of the medial collateral ligament in both knees; as well as a collapsed lung, Jeff figured it was a good idea to take his interest in sports off the ice and in to the classroom.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.