COVID messages missing vulnerable Manitobans, community advocates say Low-income residents without stable housing, access to TV and internet, people who don't speak English at higher risk

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/12/2020 (1546 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Nine months in to the COVID-19 pandemic, lowest-income Manitobans are among the hardest hit by the virus and public-health advisories haven’t made their way to all vulnerable groups.

Manitobans who don’t have stable housing, credit cards or access to the internet, news media or non-shared food and hygiene supplies are contracting the virus at rates that are likely higher than what official provincial data captures, considering some are reluctant to get tested, community advocates say.

“People don’t have the knowledge they need at a very basic level. People, (even those), that have homes, they’re trying to keep food on their tables,” said Angela McCaughan, executive director of Sscope Inc., a non-profit that is providing a 55-bed shelter space in the former Neechi Commons building on Main Street.

“They’re not thinking about COVID-19. They’re thinking about their next meal. And then you’ve got such a large proportion of addicts; they’re thinking of their next fix, not whether they’re going to get COVID-19.”

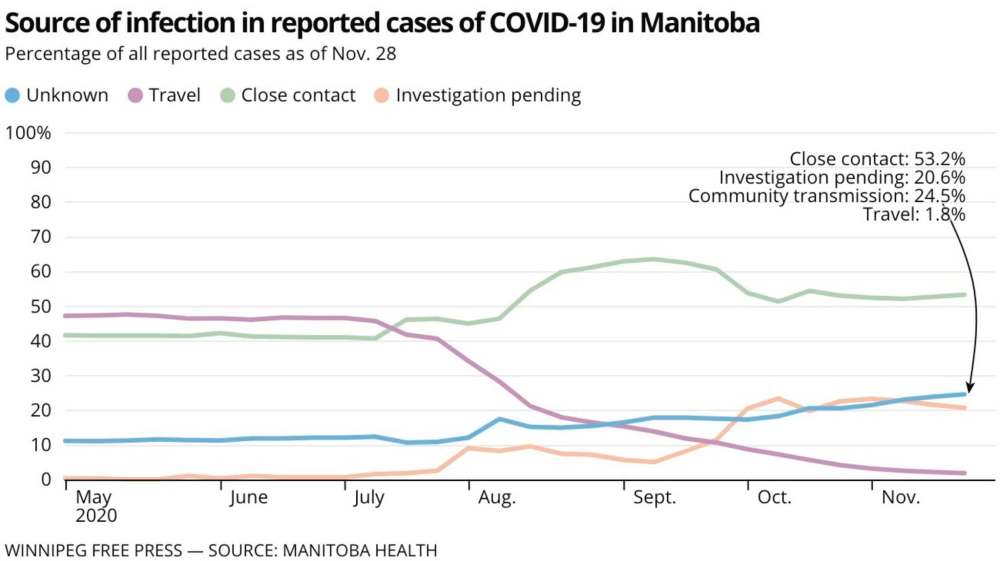

As community transmission of COVID-19 has doubled in Manitoba, the province hasn’t done enough to protect its most vulnerable residents from the virus, McCaughan said.

“And the fact that we haven’t done enough to protect them from this virus has also made everybody else in society vulnerable,” she said.

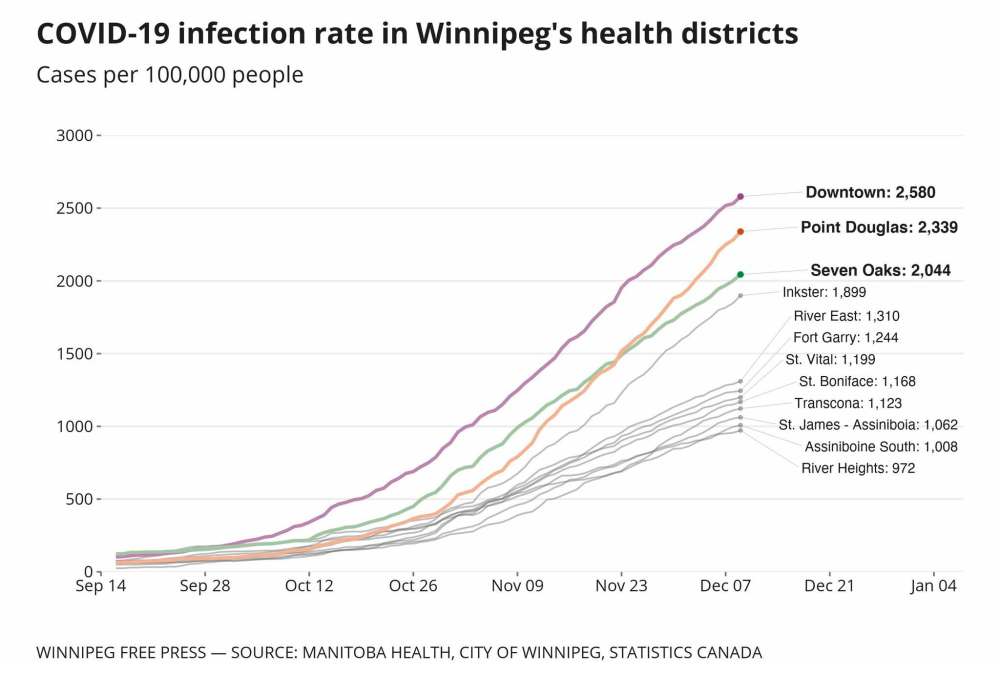

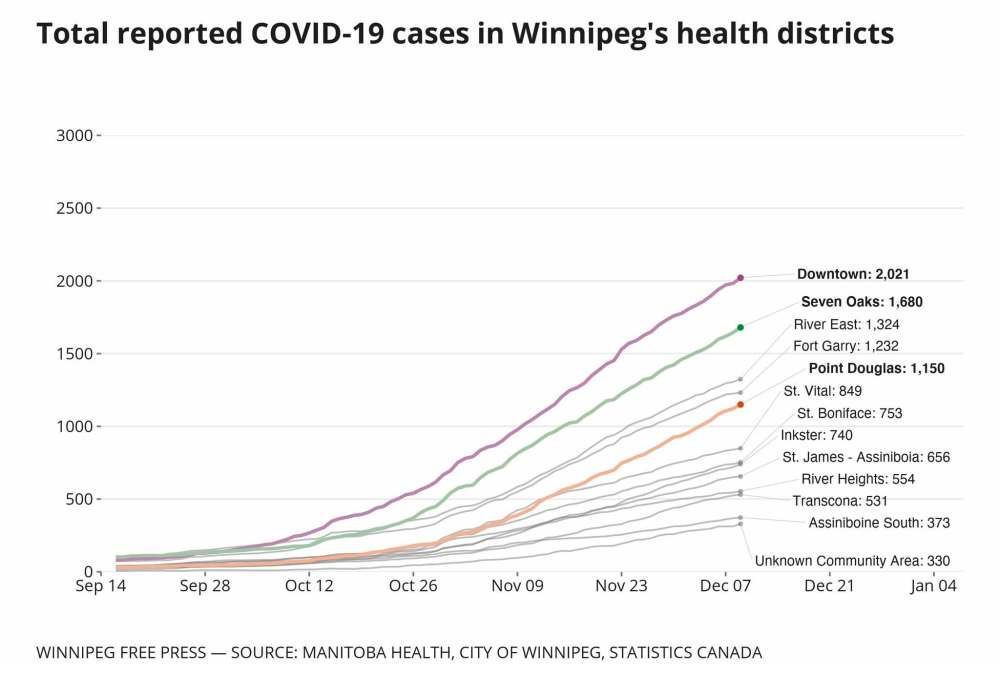

This week, Manitoba chief public health officer Dr. Brent Roussin pointed for the first time to high proportions of COVID-19 cases among low-income residents in Winnipeg’s downtown and Point Douglas areas, saying the spread is, at least partially, linked to people who are homeless or living in shelters.

“We are trying to find ways to target those groups to help better address challenges that are more unique in those circumstances,” Roussin said Monday.

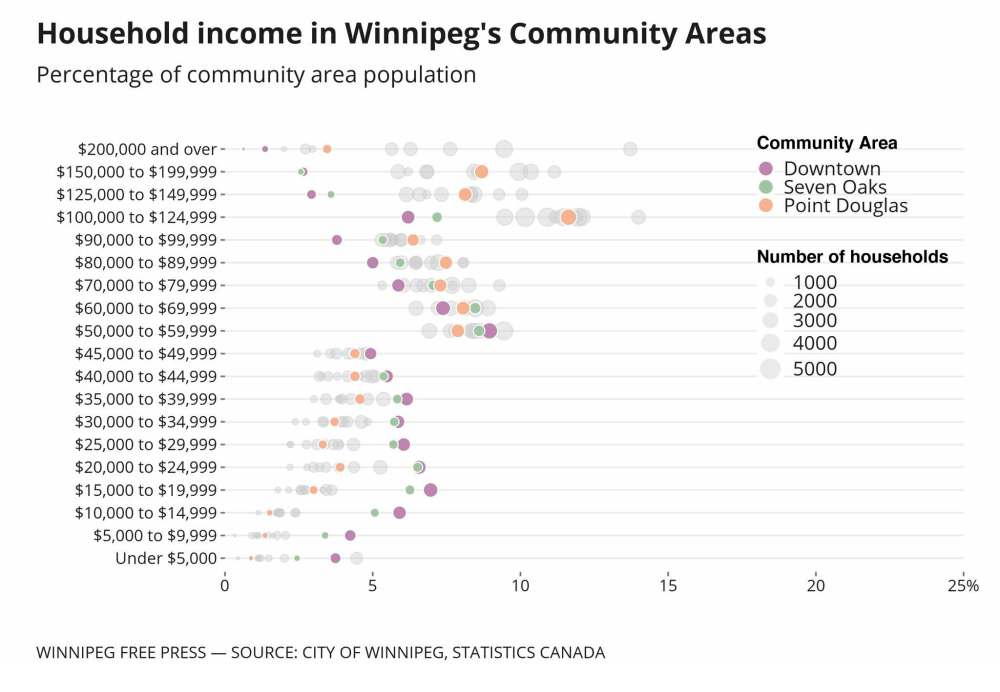

The downtown and Point Douglas areas currently have the highest COVID-19 infection rates and are home to some of the lowest-income households in the city, data compiled by the Free Press shows. Personal-care homes located in both areas have experienced COVID-19 outbreaks.

Meanwhile, community advocates are working to make sure public-health guidelines and information about provincial restrictions reach those who need them. Sel Burrows, founder of the Point Powerline in North Point Douglas, recently started distributing plain-language flyers, explaining the virus can be spread when people spit and warning residents to “wear the damn mask and don’t stand close to people.”

“Government definitely should be looking at specific ways of communicating with lower-income folk, because (community spread is) going to continue to mushroom,” Burrows said.

And it’s not just a problem in Point Douglas.

Lorie English, head of West Central Women’s Resource Centre, said the WRHA started issuing COVID-19 guidance in different languages a few months ago, something community groups had already been doing.

Even when there isn’t a language gap, not everyone has a TV or internet access to keep up with COVID-19 updates and stay on top of ever-changing public-health orders.

“Many of them don’t understand how serious this is; they don’t understand community transmission,” English said.

Her organization hands out dozens of food hampers to families who used to take advantage of school breakfasts. They often lack the money to buy groceries in bulk, meaning multiple trips on public transit to get food, instead of staying home.

“Isolation doesn’t work for folks who are low-income,” she said.

And COVID testing centres pose a similar problem, with the closest located at Thunderbird House, about 2.5 kilometres away. An available service to transport people to and from the site using Blueline taxis requires them have a phone number, and rides often don’t arrive for an hour.

“We need more thought-out solutions so that folks who are trying to do the right thing… going to be tested, have solutions that work for them,” she said.

The most vulnerable are living in rooming houses or shelters, and those using drugs are advised not to do so alone because of a rise in deadly opioid overdoses.

Lower-income people are the ones doing essential work, often in multiple workplaces, and have more physical contacts, particularly if they’re couch-surfing or sleeping in shelters. Those trying to access employment resources or apply for benefits can’t visit libraries or community centres to use photocopiers, phones and computers, community advocates said.

Dorota Blumczynska, head of the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba, said people new to Canada face more than just language barriers.

The interplay of federal departments, Shared Health, the WRHA and neighbourhood health centres is far from clear to many newcomers, as is the difference between a public-health suggestion versus an order that can carry a financial penalty.

“What is it you’re being asked to do in the course of good citizenship, versus what are you required to do by law, and is this being monitored?” Blumczynska said, arguing everyone wants to be careful but some families juggling multiple jobs can’t follow all the advice.

She said Roussin’s comments about community spread occurring in multigenerational homes likely referred to immigrant families who have grandparents raising children for parents who are out working.

“The definitions of family vary enormously across communities,” she said.

Point Douglas MLA Bernadette Smith argues the province needs to ramp up its contact with front-line service groups in the city and spend more on everything from housing to public-health messaging to addictions support.

“We knew it was going to hit Point Douglas probably harder than any other area in the city, because of all these reasons,” Smith said. “We have a huge homeless population, there’s lots of poverty here, there’s language issues.”

The province has rolled out various supports and extended funding for families involved in the child-welfare system, but Smith says there needs to be a co-ordinated plan for the city’s most vulnerable neighbourhoods.

— With files from Michael Pereira

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May

Reporter

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.