An esteemed Manitoban passes the torch

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/12/2020 (1836 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

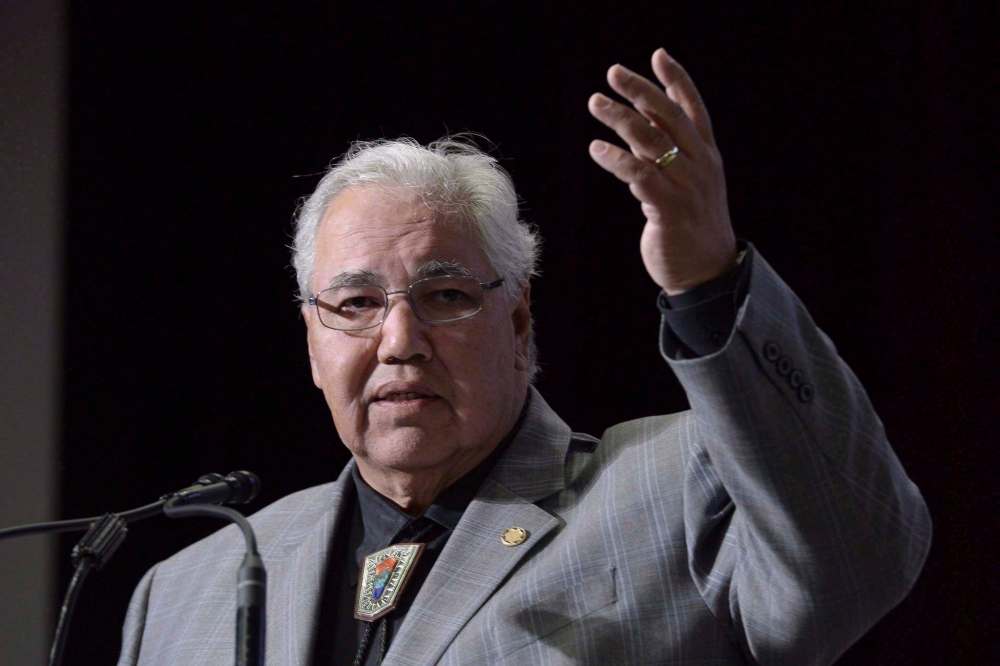

Murray Sinclair leaves a lasting legacy and an example for future generations to follow thanks to his years of working to reform Canada’s legal system and his high-profile duties as a public servant.

He announced Monday he will retire from the Senate on Jan. 31, 2021, after serving almost five years in Canada’s upper house.

His time in the Senate is a postscript to an illustrious legal career, which he began in 1980 as a pioneer: an Indigenous lawyer in Manitoba courtrooms, representing Indigenous clients in a system dominated by non-Indigenous people.

In 1988 he would make history by becoming Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge, and in 2001 would do so again by being the first Indigenous justice on Manitoba’s Court of Queen’s Bench.

He presided over two key commissions during days on the bench that would change how Canadians and their institutions would address generations of disgraceful relations with Indigenous people.

Mr. Sinclair has become widely known for his work as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which was created in 2007 in response to a class-action lawsuit involving Canada’s government-sponsored residential school system.

The details the commission revealed are shocking and shameful. Decades of abuse took place at hundreds of boarding schools across the country. Children were ripped from their families and shipped to the schools, where they were punished for speaking Aboriginal languages and following their cultural practices. Many horror stories were told by more than 7,000 witnesses, and researchers found more than 3,000 students had died, mostly from disease, a number Mr. Sinclair said was likely closer to 6,000.

He is also known for being the co-commissioner of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, which began in 1988 to focus on two deaths of Indigenous Manitobans: the 1971 murder of Helen Betty Osborne in The Pas and the 1988 shooting death of J.J. Harper after an altercation with a Winnipeg police officer. The inquiry’s final report went far beyond those two deaths and the justice system, though. It included almost 300 recommendations that span Aboriginal life in Manitoba, including treaty relations, child welfare and resource development.

It also recommended that more Aboriginal people get involved in Canada’s justice system.

So it is fitting that Mr. Sinclair, while retiring from the Senate at the age of 69, isn’t quitting on improving the relationship between Aboriginal people and the courts. He had already joined Winnipeg’s Cochrane Saxberg LLP, Manitoba’s largest Indigenous law firm, as a general counsel, and said in Monday’s announcement he aims to use that position to mentor young Indigenous lawyers.

He’s offering to pass the torch, one that has burned brightly for four decades during Mr. Sinclair’s time as lawyer, judge, senator and advocate.

It’s up to the next generation of Manitobans, whether they become lawyers or not, whether they are Indigenous or not, to pick up that torch and carry on with Mr. Sinclair’s legacy of making Manitoba’s justice system more just for Indigenous people.